Reconstruction Amendments

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Constitution of the United States |

|---|

|

| Preamble and Articles |

| Amendments to the Constitution |

|

Unratified Amendments: |

| History |

| Full text |

The Reconstruction Amendments, or the Civil War Amendments, are the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments to the United States Constitution, adopted between 1865 and 1870.[1] The amendments were a part of the implementation of the Reconstruction of the American South which occurred after the Civil War.

The Thirteenth Amendment (proposed in 1864 and ratified in 1865) abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except for those duly convicted of a crime.[2] The Fourteenth Amendment (proposed in 1866 and ratified in 1868) addresses citizenship rights and equal protection of the laws for all persons. The Fifteenth Amendment (proposed in 1869 and ratified in 1870) prohibits discrimination in voting rights of citizens on the basis of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude."[3]

These amendments were intended to guarantee the freedom of the formerly enslaved and grant certain civil rights to them, and to protect the formerly enslaved and all citizens of the United States from discrimination. However, the promise of these amendments was eroded by state laws and federal court decisions throughout the late 19th century. It was not fully realized until the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and laws such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Background

[edit]The Reconstruction Amendments were adopted between 1865 and 1870,[1] the five years which immediately followed the Civil War.[4] The last time the Constitution had been amended was with the Twelfth Amendment more than 60 years earlier in 1804.

These three amendments were part of a large movement to reconstruct the United States that followed the Civil War. Their proponents believed that they would transform the United States from a country that was (in Abraham Lincoln's words) "half slave and half free"[5] to one in which the constitutionally guaranteed "blessings of liberty" would be extended to the entire populace, including the formerly enslaved and their descendants.

Thirteenth Amendment

[edit]

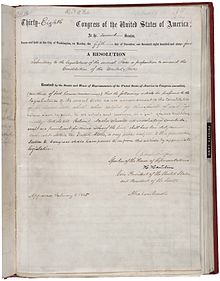

The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution abolished slavery and involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for a crime.[6] It was passed by the U.S. Senate on April 8, 1864, and, after one unsuccessful vote and extensive legislative maneuvering by the Lincoln administration, the House followed suit on January 31, 1865.[7] The measure was swiftly ratified by all but three Union states (the exceptions were Delaware, New Jersey, and Kentucky), and by a sufficient number of border and "reconstructed" Southern states, to be ratified by December 6, 1865.[7] On December 18, 1865, Secretary of State William H. Seward proclaimed it to have been incorporated into the federal Constitution. It became part of the Constitution 61 years after the Twelfth Amendment, the longest interval between constitutional amendments to date.[8]

Slavery had been tacitly enshrined in the original Constitution through provisions such as Article I, Section 2, Clause 3, commonly known as the Three-Fifths Compromise, which detailed how each state's total enslaved population would be factored into its total population count for the purposes of apportioning seats in the United States House of Representatives and direct taxes among the states.[9] Although many enslaved people had been declared free by Lincoln's 1863 Emancipation Proclamation, their legal status after the Civil War was uncertain.[10]

Fourteenth Amendment

[edit]The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was proposed by Congress on June 13, 1866.[7] By July 9, 1868, it had received ratification by the legislatures of the required number of states in order to officially become the Fourteenth Amendment.[7] On July 20, 1868, Secretary of State William Seward certified that it had been ratified and added to the federal Constitution.[11] The amendment addresses citizenship rights and equal protection of the laws and was proposed in response to issues related to the treatment of freedmen following the war. The amendment was bitterly contested, particularly by Southern states, which were forced to ratify it in order to return their delegations to Congress. The Fourteenth Amendment is one of the most litigated parts of the Constitution, forming the basis for landmark decisions such as Roe v. Wade (1973), regarding abortion, and Bush v. Gore (2000), regarding the 2000 presidential election.[12][13]

The amendment's first section includes several clauses: the Citizenship Clause, the Privileges or Immunities Clause, the Due Process Clause, and the Equal Protection Clause. The Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship, overruling the Supreme Court's decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), which had held that Americans descended from Africans could not be citizens of the United States. The Privileges or Immunities Clause has been interpreted in such a way that it does very little. While "Section 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment reduces congressional representation for states that deny suffrage on racial grounds," it was not enforced after southern states disenfranchised blacks in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[14] While Northern Congressmen in 1900 raised objections to the inequities of southern states being apportioned seats based on total populations when they excluded blacks, Southern Democratic Party representatives formed such a powerful bloc that opponents could not gain approval for change of apportionment.[15]

The Due Process Clause prohibits state and local government officials from depriving persons of life, liberty, or property without legislative authorization. This clause has also been used by the federal judiciary to make most of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states, as well as to recognize substantive and procedural requirements that state laws must satisfy.[16]

The Equal Protection Clause requires each state to provide equal protection under the law to all people within its jurisdiction. This clause was the basis for the U.S. Supreme Court's ruling in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, and its prohibition of laws against interracial marriage, in its ruling in Loving v. Virginia (1967).[17][18]

Fifteenth Amendment

[edit]

The Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the federal and state governments from denying a citizen the right to vote based on that citizen's "race, color, or previous condition of servitude." It was ratified on February 3, 1870, as the third and last of the Reconstruction Amendments.[7]

In some of the early United States, such as New Jersey prior to 1807, citizens of all races, regardless of prior enslavement, could vote provided that they could meet other requirements like property ownership.[19] But by 1869, voting rights were restricted in all states to white men. The narrow election of Ulysses S. Grant to the presidency in 1868 convinced a majority of Republicans that protecting the franchise of black men was important for the party's future. After rejecting broader versions of a suffrage amendment, Congress proposed a compromise amendment banning franchise restrictions on the basis of race, color, or previous servitude on February 26, 1869. The amendment survived a difficult ratification fight and was adopted on March 30, 1870.[20] After blacks gained the vote, the Ku Klux Klan directed some of their attacks to disrupt their political meetings and intimidate them at the polls, to suppress black participation.[21] In the mid-1870s, there was a rise in new insurgent groups, such as the Red Shirts and White League, who acted on behalf of white supremicists calling themselves "Redeemers", to violently suppress black voting.[22] While Redeemers in the Democrats regained local power in southern state legislatures, through the 1880s and early 1890s, numerous blacks continued to be elected to local offices in many states, as well as to Congress as late as 1894.[23]

Beginning around 1900, states in the former Confederacy passed new constitutions and other laws that incorporated methods to disenfranchise blacks, such as poll taxes, residency rules, and literacy tests administered by white staff, sometimes with exemptions for whites via grandfather clauses.[23] When challenges reached the Supreme Court, it interpreted the amendment narrowly, ruling based on the stated intent of the laws rather than their practical effect. The results in voter suppression were dramatic, as voter rolls fell: nearly all blacks, as well as tens of thousands of poor whites in Alabama and other states,[24] were forced off the voter registration rolls and out of the political system, effectively excluding millions of people from representation.[25]

In the twentieth century, the Court interpreted the amendment more broadly, striking down grandfather clauses in Guinn v. United States (1915).[26] It took a quarter-century to finally dismantle the white primary system in the "Texas primary cases" (1927–1953). With the South having become a one-party[which?] region after the disenfranchisement of blacks, Democratic Party primaries were the only competitive contests in those states.[further explanation needed] But Southern states reacted rapidly to Supreme Court decisions, often devising new ways to continue to exclude blacks from voter rolls and voting; most blacks in the South did not gain the ability to vote until after the passage of the mid-1960s federal civil rights legislation and the beginning of federal oversight of voter registration and district boundaries. The Twenty-fourth Amendment (1964) forbade the requirement for poll taxes in federal elections; by this time five of the eleven southern states continued to require such taxes. Together with the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections (1966), which forbade requiring poll taxes in state elections, blacks regained the opportunity to participate in the U.S. political system.[27]

Erosion, litigation, and scope

[edit]The promise of these amendments was eroded by state laws and federal court decisions throughout the late 19th century before being restored in the second half of the twentieth century. In 1876 and beyond, some states passed Jim Crow laws that limited the rights of African-Americans. Important Supreme Court decisions that undermined these amendments were the Slaughter-House Cases in 1873, which prevented rights guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment's privileges or immunities clause from being extended to rights under state law;[28] and Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 which originated the phrase "separate but equal" and gave federal approval to Jim Crow laws.[29] The full benefits of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments were not realized until the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and laws such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.[30] The Reconstruction Amendments affected the constitutional division of power between U.S. state governments and the federal government of the United States,[31] for the Reconstruction Amendments "were specifically designed as an expansion of federal power and an intrusion on state sovereignty."[32] The United States Supreme Court observed in 2024 with a view to the Fourteenth Amendment and thus the Reconstruction Amendments in general: "The Fourteenth Amendment “expand[ed] federal power at the expense of state autonomy” and thus “fundamentally altered the balance of state and federal power struck by the Constitution.” Seminole Tribe of Fla. v. Florida, 517 U. S. 44, 59 (1996); see also Ex parte Virginia, 100 U. S. 339, 345 (1880)."[33]

See also

[edit]- Crittenden Compromise

- Corwin Amendment

- National Freedom Day

- Reconstruction Acts

- Forty acres and a mule

- Ballot access in the United States

- Black suffrage in the United States

- Voting rights in the United States

- List of amendments to the United States Constitution

- Slavery Abolition Act 1833 (United Kingdom)

References

[edit]- ^ a b "U.S. Senate: Landmark Legislation: Thirteenth, Fourteenth, & Fifteenth Amendments". www.senate.gov. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved January 3, 2021.

- ^ "America's Historical Documents". National Archives. National Archives and Records Administration. January 25, 2016. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ "The 15th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution". National Constitution Center – The 15th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- ^ "(1865) Reconstruction Amendments, 1865-1870". BlackPast.org. January 21, 2007. Retrieved January 7, 2021.

- ^ Springfield, Mailing Address: 413 S. 8th Street; Us, IL 62701 Phone:492-4241 Contact. "House Divided Speech - Lincoln Home National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Greene, Jamal; McAward, Jennifer Mason. "The Thirteenth Amendment". Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "All Amendments to the United States Constitution". hrlibrary.umn.edu. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ "The Constitution of the United States: Amendments 11-27". United States National Archives. Archived from the original on May 26, 2013. Retrieved February 24, 2014.

- ^ Allain, Jean (2012). The Legal Understanding of Slavery: From the Historical to the Contemporary. Oxford University Press. p. 117. ISBN 9780199660469.

- ^ "What The Emancipation Proclamation Didn't Do". NPR.org. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875". memory.loc.gov. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved August 21, 2020.

- ^ Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113 (1973).

- ^ Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000).

- ^ "Committee at Odds on Reapportionment: Three Reports on the Bill Submitted to the House" (PDF). The New York Times. December 21, 1990. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 11, 2020. Retrieved November 25, 2018.

- ^ Valelly, Richard M. (October 2, 2009). The Two Reconstructions: The Struggle for Black Enfranchisement. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226845272. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ "BRIA 7 4 b The 14th Amendment and the "Second Bill of Rights"". www.crf-usa.org. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

- ^ Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)

- ^ "Did You Know: Women and African Americans Could Vote in NJ before the 15th and 19th Amendments?". National Park Service. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ^ "Passage of the Fifteenth Amendment | American Experience | PBS". www.pbs.org. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "Historical Voter Suppression – Notley Scholars Voter Rights Project". Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Michael Perman (2009). Pursuit of Unity: A Political History of the American South. Univ of North Carolina Press. pp. 138–139. ISBN 978-0-8078-3324-7. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ a b Jervis, Rick. "Black Americans got the right to vote 150 years ago, but voter suppression still a problem". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Feldman, Glenn (2004). The Disfranchisement Myth Poor Whites and Suffrage Restriction in Alabama. University of Georgia Press. p. 135. OCLC 474353255.

- ^ Pildes, Richard H. (July 13, 2000). "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon". Constitutional Commentary. 17. Rochester, NY: 295–319. doi:10.2139/ssrn.224731. hdl:11299/168068. SSRN 224731. Archived from the original on December 30, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Guinn v. United States, 238 U.S. 347 (1915)

- ^ Harper v. Virginia Bd. of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966)

- ^ Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. 36.

- ^ Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537.

- ^ Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483.

- ^ Sherrilyn A. Ifill (October 28, 2015). "Freedom Still Awaits". The Atlantic. The Atlantic. Archived from the original on June 6, 2023. Retrieved May 5, 2024.

- ^ "City of Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156 (1980), at 179". Justia US Supreme Court Center. April 22, 1980. Archived from the original on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

- ^ "Trump v. Anderson, 601 U.S. ___ (2024), Per Curiam, at page 4" (PDF). United States Supreme Court. March 4, 2024. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2024.

External links

[edit]- The Reconstruction Amendments: Essential Documents (2 vols) (Kurt T. Lash, ed.) (University of Chicago Press, 2021)

- Reconstruction Amendments

- 1860s in the United States

- 1865 in American law

- 1865 in American politics

- 1866 in American law

- 1866 in American politics

- 1867 in American law

- 1867 in American politics

- 1868 in American law

- 1868 in American politics

- 1869 in American law

- 1869 in American politics

- 1870 in American law

- 1870 in American politics

- Amendments to the United States Constitution

- Politics of the American Civil War

- Reconstruction Era

- United States slavery law