Raytheon

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2024) |

Raytheon's former headquarters complex in Waltham, Massachusetts | |

| Company type | Public |

|---|---|

| NYSE: RTX | |

| Industry | Aerospace and defense |

| Founded | July 7, 1922, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Founder | Vannevar Bush Laurence K. Marshall Charles G. Smith |

| Defunct | April 3, 2020 |

| Fate | Merged with United Technologies |

| Successor | RTX Corporation |

| Headquarters | Waltham, Massachusetts, U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Phil Jasper (chairman and CEO) |

| Revenue | US$29.18 billion (2019) |

| US$3.34 billion (2019) | |

Number of employees | ~67,000 (2018) |

| Website | raytheon.com (Archived) |

| Footnotes / references [1][2] | |

The Raytheon Company was a major U.S. defense contractor and industrial corporation with manufacturing concentrations in weapons and military and commercial electronics. Founded in 1922, it merged in 2020 with United Technologies Corporation to form Raytheon Technologies,[3] which changed its name to RTX Corporation in July 2023.

Raytheon was established in 1922, reincorporated in 1928, and adopted the Raytheon Company name in 1959. More than 90% of Raytheon's revenues were obtained from military contracts and, as of 2012, it was the fifth-largest military contractor in the world.[4] As of 2015[update], it was the third-largest defense contractor in the United States by defense revenue.[5] It was the world's largest producer of guided missiles, and was involved in corporate and special-mission aircraft until early 2007.[6] In 2018, the company had around 67,000 employees worldwide and annual revenues of about US$25.35 billion.[7]

Over the years, Raytheon shifted its headquarters among various Massachusetts locations: Cambridge from 1922 to 1928; Newton until 1941; Waltham until 1961; and finally, Lexington until 2003.[8]

History

[edit]

Early years

[edit]In 1922, Vannevar Bush, scientist and professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), along with engineer and physicist Laurence K. Marshall, and scientist Charles G. Smith, founded the American Appliance Company in Cambridge, Massachusetts.[9] Its focus, which was originally on new refrigeration technology, soon shifted to electronics. The company's first product was a gaseous (helium) voltage-regulator tube that was based on Charles Smith's earlier astronomical research of the star Zeta Puppis.[10] The electron tube was christened with the name Raytheon (a compound of Old French and Greek meaning 'light from the gods')[11] and was used in a battery eliminator, a type of radio-receiver power supply that plugged into the power grid in place of large batteries. This made it possible to convert household alternating current to a regulated, high voltage direct current for radios and thus eliminate the need for expensive, short-lived batteries.

In 1925, the company changed its name to Raytheon Manufacturing Company and began marketing its rectifier, under the Raytheon brand name, with commercial success. In 1928 Raytheon merged with Q.R.S. Company, an American manufacturer of electron tubes and switches, to form the successor of the same name, Raytheon Manufacturing Company.[citation needed] By the 1930s, it had already grown to become one of the world's largest vacuum tube manufacturing companies.[citation needed] In 1933 it diversified by acquiring Acme-Delta Company, a producer of transformers, power equipment, and electronic auto parts.[citation needed]

During World War II

[edit]Early in World War II, physicists in the United Kingdom invented the magnetron, a specialized microwave-generating electron tube that markedly improved the capability of radar to detect enemy aircraft. American companies were then sought by the US government to perfect and mass-produce the magnetron for ground-based, airborne, and shipborne radar systems, and, with support from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Radiation Laboratory (recently formed to investigate microwave radar), Raytheon received a contract to build the devices. Within a few month, Raytheon began to manufacture magnetron tubes for use in radar sets, and then complete radar systems. During the war, Raytheon also pioneered the production of shipboard radar systems, particularly for submarine detection. Raytheon was also a contractor for the mass-production of miniature shock-resistant vacuum tubes used in proximity fuses. These tubes were difficult to manufacture and required rigorous attention to detail.[12] At war's end in 1945, the company had built about 80 percent of all magnetrons. Raytheon ranked 71st among U.S. corporations in the value of World War II military production contracts.[13]

In 1945, Raytheon's Percy Spencer invented the microwave oven by discovering that the magnetron could rapidly heat food. In 1947, the company demonstrated the Radarange microwave oven for commercial use.[14]

After World War II

[edit]During the post-war years, Raytheon also made generally low- to medium-powered radio and television transmitters and related equipment for the commercial market, but the high-powered market was solidly in the hands of larger, better-financed competitors such as Continental Electronics, General Electric and Radio Corporation of America.

In 1946, the company expanded its electronics capability through acquisitions that included the Submarine Signal Company (founded in 1901), a leading manufacturer of maritime safety equipment. With its broadened capabilities, Raytheon developed the first guidance system for a missile that could intercept a flying target. In 1948, Charles Francis Adams IV was appointed president of the company and served until 1960. In 1948, Raytheon began to manufacture guided missiles. In 1950, its Lark became the first such missile to destroy a target aircraft in flight. Raytheon then received military contracts to develop the air-to-air Sparrow and ground-to-air Hawk missiles, projects that received impetus from the Korean War. In later decades, it remained a major producer of missiles, such as the Patriot antimissile missile and the air-to-air Phoenix missile.

Raytheon made a foray into computers, producing the RAYDAC computer for the U.S. Navy which became operational in 1953. "Unfortunately, the machine was technically obsolete by the time it was operational."[citation needed] Also in 1953, the company began work on a follow-on, the RAYCOM, which was never completed.[15] In 1954, it entered into a joint venture with Honeywell to form the Datamatic corporation. However it sold its interest to Honeywell a year later, before introduction of the DATAmatic 1000 system.

In 1958, Raytheon acquired the marine electronics company Applied Electronics Company to make commercial marine navigation and radio gear, as well as less-expensive Japanese suppliers of products such as marine/weather band radios and direction-finding gear.[16][failed verification] In the same year, it changed its name to Raytheon Company.

In the 1950s, Raytheon began manufacturing transistors, including the CK722, priced and marketed to hobbyists.

In 1961, the British electronics company A.C. Cossor merged with Raytheon, following its sale by Philips. The new company's name was Raytheon Cossor. The Cossor side of the organisation was still in the Raytheon group in 2010.

In 1965, it acquired Amana Refrigeration, Inc., a manufacturer of refrigerators and air conditioners. Using the Amana brand name and its distribution channels, Raytheon began selling the first countertop household microwave oven in 1967 and became a dominant manufacturer in the microwave oven business.

In 1966, the company entered the educational publishing business with the acquisition of D.C. Heath and Company, marketing an influential physics textbook developed by the Physical Science Study Committee. Raytheon also manufactured the Apollo Guidance Computer, which was introduced that year and flew aboard all NASA Project Apollo missions.

In the late 1970s, Raytheon acquired McGraw-Edison's appliances division notable for the Speed Queen line of washers and dryers.

1980s

[edit]In 1980, Raytheon acquired Beech Aircraft Corporation, a leading manufacturer of general aviation aircraft founded in 1932 by Walter H. Beech. In 1993, the company expanded its aircraft activities by adding the Hawker line of business jets by acquiring Corporate Jets Inc., the business jet product line of British Aerospace (now BAE Systems). These two entities were merged in 1994 to become the Raytheon Aircraft Company. In the first quarter of 2007 Raytheon sold its aircraft operations, which subsequently operated as Hawker Beechcraft, and since 2014 have been units of Textron Aviation. The product line of Raytheon's aircraft subsidiary included business jets such as the Hawker 800XP and Hawker 4000, the Beechjet 400A, and the Premier I; the popular King Air series of twin turboprops; and piston-engine aircraft such as the Bonanza. Its special-mission aircraft included the single-turboprop T-6A Texan II, which the United States Air Force and United States Navy had chosen as their primary training aircraft.

1990s

[edit]In 1991, during the Persian Gulf War, Raytheon's Patriot missile received great international exposure, resulting in a substantial increase in sales for the company outside the United States. In an effort to establish leadership in the defense electronics business, Raytheon purchased in quick succession Dallas-based E-Systems (1995); Chrysler Corporation's defense electronics and aircraft-modification businesses, which had previously acquired companies such as Electrospace systems (1996) (portions of these businesses were later sold to L-3 Communications), and the defense unit of Texas Instruments, Defense Systems & Electronics Group (1997). Also in 1997, Raytheon acquired the aerospace and defense business of Hughes Aircraft Company from Hughes Electronics Corporation, a subsidiary of General Motors, which included a number of product lines previously purchased by Hughes Electronics, including the former General Dynamics missile business (Pomona facility), the defense portion of Delco Electronics (Delco Systems Operations), and Magnavox Electronic Systems. [citation needed]

Raytheon also divested itself of several nondefense businesses in the 1990s, including Amana Refrigeration, Raytheon Commercial Laundry (purchased by Bain Capital's Alliance Laundry Systems), and Seismograph Service Ltd (sold to Schlumberger-Geco-Prakla). On October 12, 1999, Raytheon exited the personal rapid transit (PRT) business as it terminated its PRT 2000[17] system due to the high cost of development and the lack of interest.[18]

2000s

[edit]During the September 11 attacks of 2001, Raytheon had an office in the South Tower of the World Trade Center on the 91st floor. Their office, being 6 floors above where United Airlines Flight 175 collided with the building, was spared from the immediate collision, but was utterly destroyed in the subsequent collapse of the South Tower.[19]

In November 2007, Raytheon purchased Sarcos for an undisclosed sum, seeking to expand into robotics research and production.[20]

In September 2009, Raytheon purchased Bolt Beranek and Newman Inc. as a wholly owned subsidiary.

2010s

[edit]

In December 2010, Applied Signal Technology agreed to be acquired by Raytheon for $490 million.[21]

In October 2014, Raytheon beat rivals Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman for a contract to build 3DELRR, a next-generation long-range radar system, for the USAF worth an estimated $1 billion.[22]

The contract award was immediately protested by Raytheon's competitors, Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman. After re-evaluating the bids following the protests,[23] the USAF decided to delay awarding the 3DELRR EMD contract until 2017 and was to issue an amended solicitation at the end of July 2016.[24] In 2017 the USAF again awarded the contract to Raytheon.[25]

In May 2015, Raytheon acquired cybersecurity firm Websense, Inc. from Vista Equity Partners for $1.9 billion[26] and combined it with RCP, formerly part of its IIS segment to form Raytheon|Websense.[27] In October 2015, Raytheon|Websense acquired Foreground Security for $62 million.[28] In January 2016, Raytheon|Websense acquired the firewall provider Stonesoft from Intel Security for an undisclosed amount and renamed itself to Forcepoint.[29]

In July 2016, Poland's Defence Minister Antoni Macierewicz planned to sign a letter of intent with Raytheon for a $5.6 billion deal to upgrade its Patriot missile-defence shield.[30][31]

In 2017, Saudi Arabia signed business deals worth billions of dollars with multiple American companies, including Raytheon.[32][33]

In July 2019, Qatar's Ministry of Defense committed to acquire Raytheon's NASAM and Patriot missile defense systems.[34] The company would later be fined for paying bribes to a Qatari officials to influence defense purchases.[35]

2020s

[edit]In February 2020, Raytheon completed the first radar antenna array for the US Army's new missile defense radar, known as the Lower Tier Air and Missile Defense Sensor (LTAMDS), to replace the service's Patriot air and missile defense system sensor.[36]

In April 2020, the company merged with United Technologies Corporation to form Raytheon Technologies.[3] The merged company is headquartered in Arlington, Virginia rather than UTC's base in Farmington, Connecticut.[37]

Raytheon was sanctioned by the Chinese government in October 2020,[38] February 2022,[39] and February 2023 due to arm sales to Taiwan.[40]

In July 2023, Raytheon Technologies renamed themselves to RTX Corporation and merged the Raytheon Intelligence & Space and Raytheon Missiles & Defense business segments to form a new Raytheon business segment.[41]

In August 2024, RTX agreed to pay a $200 million fine for the unauthorized export of defense technology to China, Russia, Iran, and elsewhere, to settle more than 750 violations of the Arms Export Control Act and the International Traffic in Arms Regulations, or ITAR. The company was allowed to pay only half the fine to the government and to put half of the fine toward “remedial compliance measures to strengthen RTX’s compliance program.”[42] In October 2024, RTX agreed to pay nearly $1 billion to settle allegations of defrauding the U.S. Defense Department and bribing a Qatari military official. Company officials said the misconduct mostly occurred before 2020 and pledged to improve its compliance programs.[35]

Finances

[edit]For the fiscal year 2017, Raytheon reported earnings of US$2.024 billion, with an annual revenue of US$25.348 billion, an increase of 5.1% over the previous fiscal cycle. Raytheon's shares traded at over $164 per share, and its market capitalization was valued at over US$51.7 billion in November 2018.[43]

| Year | Revenue in mil. US$ |

Net income in mil. US$ |

Total assets in mil. US$ |

Price per share in US$ |

Employees |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 18,491 | 871 | 24,381 | 27.58 | |

| 2006 | 19,707 | 1,283 | 25,491 | 33.92 | |

| 2007 | 21,301 | 2,578 | 23,281 | 42.79 | |

| 2008 | 23,174 | 1,672 | 23,134 | 44.40 | |

| 2009 | 24,881 | 1,935 | 23,607 | 35.95 | |

| 2010 | 25,150 | 1,840 | 24,422 | 40.55 | |

| 2011 | 24,791 | 1,866 | 25,854 | 38.75 | |

| 2012 | 24,414 | 1,888 | 26,686 | 46.38 | |

| 2013 | 23,706 | 1,996 | 25,967 | 61.96 | 63,000 |

| 2014 | 22,826 | 2,244 | 27,716 | 89.54 | 61,000 |

| 2015 | 23,321 | 2,110 | 29,281 | 102.58 | 61,000 |

| 2016 | 24,124 | 2,244 | 30,238 | 128.50 | 63,000 |

| 2017 | 25,348 | 2,024 | 30,860 | 164.75 | 64,000 |

Company structure

[edit]Businesses

[edit]Raytheon is composed of five major business divisions:[44]

- Integrated Defense Systems—based in Tewksbury, Massachusetts; Ralph Acaba, President

- Intelligence, Information and Services—based in Dulles, Virginia; Dave Wajsgras, President

- Missile Systems—based in Tucson, Arizona; Wesley Kremer, President

- Space and Airborne Systems—based in McKinney, Texas; Roy Azevedo, President

- Forcepoint—based Austin, Texas; CEO, Matt Moynahan

Raytheon's businesses are supported by several dedicated international operations including: Raytheon Australia; Raytheon Canada Limited; operations in Japan; Raytheon Microelectronics in Spain; Raytheon UK (formerly Raytheon Systems Limited); and ThalesRaytheonSystems, France.

Strategic Business Areas

[edit]In recent years, Raytheon has expanded into other fields while redefining some of its core business activities. Raytheon has identified five key 'Strategic Business Areas' where it is focusing its expertise and resources:

- Homeland Security

- Missile Defense

- Precision Engagement

- Intelligence, Surveillance, Reconnaissance (ISR)

- Process Improvement (Raytheon Lean6)

Leadership

[edit]In March 2014, Thomas Kennedy was named CEO of Raytheon Company.[45] Kennedy succeeded William H. Swanson, who was CEO since 2003. Swanson remained as Chairman through September 2014 when Kennedy became chairman as well as CEO.[46] Other current and former members of the board of directors of Raytheon were: Vernon Clark, James E. Cartwright, John Deutch, Stephen J. Hadley, George R. Oliver, Frederic Poses, Michael Ruettgers, Ronald Skates, William Spivey, and Linda Stuntz.[47]

Ownership

[edit]As of December 2014, according to filed reports, the top ten institutional shareholders of Raytheon are Wellington Management Company, Vanguard Group, State Street Corporation, Barrow, Hanley, Mewhinney & Strauss, BlackRock Institutional Trust Company, BlackRock Advisors, Bank of America, Bank of New York Mellon, Deutsche Bank and Macquarie Group.[48]

Products and services

[edit]Overview

[edit]Raytheon provides electronics, mission systems integration and other capabilities in the areas of sensing; effects; and command, control, communications and intelligence systems; as well as a broad range of mission support services.

Raytheon's electronics and defense-systems units produce air-, sea-, and land-launched missiles, aircraft radar systems, weapons sights and targeting systems, communication and battle-management systems, and satellite components.

Air traffic control systems

[edit]- FIRSTplus Air Traffic Control Simulator

- AutoTrac III ATM System

- STARS

Radars and sensors

[edit]

Raytheon is a developer and manufacturer of radars (including AESAs), electro-optical sensors, and other advanced electronics systems for airborne, naval and ground based military applications. Examples include:

- APG-63/APG-70 radars for the F-15 Eagle

- APG-65/APG-73/APG-79 radars for the F/A-18 Hornet

- APG-77 radar for the F-22 Raptor (joint development with Northrop Grumman)

- APG-84 RACR radar

- ALE-50 towed decoy

- ALR-67(V)3 and ALR-69A radar warning receivers

- AN/APQ-181 (AESA upgrade currently in development), for the B-2 Spirit bomber

- Integrated Sensor Suite (ISS) for the RQ-4 Global Hawk UAV

- ASQ-228 ATFLIR (Advanced Targeting Forward-Looking Infrared) pod

- TPQ-36/TPQ-37 Firefinder and MPQ-64 Sentinel mobile battlefield radars

- F-16 RACR, designed for the F-16 using AESA technology

- SLQ-32 shipboard EW system

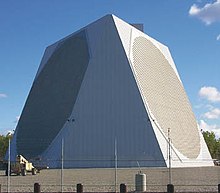

- Large fixed-site radars such as PAVE PAWS, BMEWS, and the Missile Defense Agency X-band Radar (XBR)

Satellite sensors

[edit]Raytheon, often in conjunction with Boeing, Lockheed Martin or Northrop Grumman, is also heavily involved in the satellite sensor business. Much of its Space and Airborne Systems division in El Segundo, CA is devoted to this, a business it inherited from Hughes. Examples of programs include:

- Space Tracking and Surveillance System (STSS), being developed for the Ballistic Missile Defense. Raytheon is building the sensor payload.[citation needed] Additionally, the El Segundo site is the company center of excellence for the development and production of laser products.

- Raytheon company's Navy Multiband Terminal (NMT) is the first advanced, next-generation satellite communications (SATCOM) system to successfully log on to and communicate with the U.S. government's Milstar SATCOM system using low and medium data rate waveforms. The system provides naval commanders and sailors with greater data capacity, as well as improved protection against enemy intercept and jamming.

- Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS), was developed by Raytheon Space and Airborne Sensors and is currently in operation on the Suomi NPP satellite. Future deliveries of VIIRS will fly onboard JPSS to continue the operational space based climate and weather sensing legacy of the MODIS sensors.[49]

Communications

[edit]- The company also makes several software radio and digital communication systems for military applications such as Cooperative Engagement Capability (CEC), is participating in Navy-Marine Corps Intranet (NMCI), ECHELON and the Joint Tactical Terminal (JTT) programs.

- Digital Multimedia Watchdog, a tool used by the FBI to record phone calls and Internet communications.[50]

Radioactive materials detection system

[edit]As part of the company's growing homeland security business and strategic focus, Raytheon has teamed with other contractors to develop an Advance Spectroscopic Portal (ASP) to allow border officials to view and identify radioactive materials in vehicles and shipping containers more effectively.[51]

Semiconductors

[edit]Raytheon also manufactures semiconductors for the electronics industry in sites in the US and UK. In the late 20th century it produced a wide range of integrated circuits and other components, but as of 2003 its US semiconductor business specializes in gallium arsenide (GaAs) components for radio communications as well as infrared detectors. It is also making efforts to develop gallium nitride (GaN) components for next-generation radars and radios. The UK arm specialized in CMOS on silicon carbide (SiC) development and foundry work but is no longer taking on new orders, having been on the premises for 57 years.

Missile defense systems

[edit]In the framework of Ground-Based Midcourse Defense, Raytheon is developing a Ground Based Interceptor (GBI) that includes a booster missile and a kinetic Exoatmospheric Kill Vehicle (EKV), along with several key radar components, such as the Sea-Based X-Band Radar (SBX) and the Upgraded Early Warning Radar (UEWR).

Missiles

[edit]

Raytheon is a developer of missiles and related missile defense systems. These include:

- AGM-62 Walleye

- AGM-65 Maverick

- AGM-88 HARM

- AGM-114 Hellfire

- AGM-129 Advanced Cruise Missile

- AGM-154 Joint Standoff Weapon

- AIM-7 Sparrow

- AIM-9 Sidewinder

- AIM-54 Phoenix

- AIM-120 AMRAAM

- AS-14 Kedge

- BGM-71 TOW

- BGM-109 Tomahawk

- FGM-148 Javelin

- FIM-92 Stinger

- GBU-28 Paveway III

- Peregrine air-to-air missile[52]

- MIM-23 Hawk

- MIM-104 Patriot

- RIM-7 Sea Sparrow

- RIM-161 Standard Missile 3

- RIM-162 ESSM

- Pyros

Environmental record

[edit]Two lawsuits were filed against a Raytheon Company plant in St. Petersburg, Florida, due to concern with health risks, property values, and contamination in April 2008.[53] Raytheon was given until the end of the month to independently test whether or not the groundwater that originated from its area was contaminated. According to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), the groundwater contained carcinogenic contaminants, including trichloroethylene, 1,4-dioxane, and vinyl chloride.[54] The DEP also reported that the clouds contained other toxins, such as lead and toluene.[53]

In 1995, Raytheon acquired Dallas-based E-Systems, including a site in St. Petersburg, Florida, In November 1991, prior to Raytheon's acquisition, contamination had been discovered at the E-Systems site. Soil and groundwater had been contaminated with the volatile organic compounds trichloroethylene and 1,4-Dioxane. In 2005, groundwater monitoring indicated polluted groundwater was moving into areas outside the site.[55] According to DEP documentation, Raytheon has tested wells on its site since 1996 but had not delivered a final report; therefore, it was given a deadline on May 31, 2008, to investigate its groundwater.[53] Contamination in the area has not affected anyone's drinking water supply or health, yet due to negative local media coverage lawsuits are being filed with claims against Raytheon citing decreases in property values.[56]

In another case, Raytheon was ordered by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to treat groundwater at the Tucson Plant (acquired during the merger with Hughes) in Arizona since Raytheon used and disposed metals, chlorinated solvents, and other substances at the plant since 1951.[57] The EPA further required the installation and operation of an oxidation process system to treat the solvents and make the water safe to drink.[57]

On 9 August 2006, The Stream Contact Centre in Derry, Northern Ireland, which had a contract with Raytheon at the time, was attacked by protesters. They destroyed the computers, documents, and mainframe of the office, and proceeded to occupy it for eight hours prior to their arrest.

The activists were charged with criminal damage and affray under terrorism laws.[58] The trial of six of the accused began May 19, 2008, in the Laganside Courts in Belfast. Colm Bryce, Gary Donnelly, Kieran Gallagher, Michael Gallagher, Sean Heaton, Jimmy Kelly, Paddy McDaid and Eamonn O'Donnell were acquitted of all charges on 11 June, with Eamonn McCann found guilty of the theft of two computer discs.

By 2013, the company was also awarded the Goal Achievement Award by the EPA for excellence in greenhouse gas management.[59]

See also

[edit]- Tactical Control System

- Top 100 US Federal Contractors – $16.1 billion in FY2009

References

[edit]- ^ "Raytheon Company 2017 Annual Report (Form 10-K)". sec.gov. United States Securities and Exchange Commission. January 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-04-05. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-01-04. Retrieved 2015-01-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b Kilgore, Tomi (April 4, 2020). "Raytheon Technologies' stock, formerly United Technologies, starts trading in". MarketWatch. Archived from the original on 2020-07-13. Retrieved 2020-04-03.

- ^ "Defense News Top 100". Defense News Research. 2012. Archived from the original on April 8, 2013. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- ^ "Top 100 for 2015." Archived 2015-07-31 at archive.today Defense News. 2015. Retrieved on 2016-07-26.

- ^ Missile maker hopes to diversify, create technology for peacetime Archived 2012-02-11 at the Wayback Machine. Sazhightechconnect.com. Retrieved on 2012-02-04.

- ^ "Raytheon". Fortune. Archived from the original on 2019-12-27. Retrieved 2019-06-11.

- ^ "New Raytheon Headquarters to Open Oct. 27 in Waltham, Mass". 2003-10-22. Archived from the original on 2019-12-24. Retrieved 2019-09-18.

- ^ Raytheon Australia. History. Archived 2007-08-30 at the Wayback Machine Raytheon Marketing Material.

- ^ Otto J. Scott, The Creative Ordeal, (New York, Atheneum, 1974),16–32

- ^ "100 Years of Era-Defining Innovation: Celebrating the Centennial Anniversary of Raytheon Company". Raytheon Technologies. Raytheon Technologies Corporation. Archived from the original on January 29, 2023. Retrieved January 29, 2023.

- ^ Holmes, Jamie. 12 Seconds Of Silence: How a Team of Inventors, Tinkerers, and Spies Took Down a Nazi Superweapon. Mariner Books, 2020, 416 pp.

- ^ Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p.619

- ^ "Technology Leadership". Raytheon. Archived from the original on 2013-03-22.

- ^ Flamm, Kenneth (2010). Creating the Computer: Government, Industry and High Technology. Brookings Institution Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-8157-2850-4. Retrieved Aug 21, 2019.

- ^ "Raytheon Buys Electronics Co. in South City". San Francisco Examiner. 5 February 1958. p. 6. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ PRT 2000 System Concept Archived 2023-04-22 at the Wayback Machine, "Design and Commercialization of the PRT 2000 Personal Rapid Transit System" by S. J. Gluck, R. Tauber and B. Schupp. University of Washington Web Server.

- ^ Raytheon PRT Prospects Dim but not Doomed. Peter Samuel. Archived 2023-08-13 at the Wayback Machine October 1999.

- ^ "Building: 2 World Trade Center - South Tower". www.edition.cnn.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-19. Retrieved 2023-09-18.

- ^ Jump up ^ Staff (2007-11-14). "Business Briefs". The Lowell Sun (MediaNews Group).

- ^ Hubler, David (Dec 20, 2010). "Raytheon buys Applied Signal Technology". Washington Technology. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019. Retrieved Aug 21, 2019.

- ^ Raytheon wins deal for next-generation U.S. Air Force radar Archived 2021-05-16 at the Wayback Machine. Reuters, 7 October 2014

- ^ Mehta, Aaron (22 January 2015). "US Air Force to Reevaluate 3DELRR Award". Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ USAF delays awarding 3DELRR EMD contract until 2017 Archived 2016-07-16 at the Wayback Machine. Janes, 15 July 2016

- ^ Mehta, Aaron (2017-08-08). "Raytheon awarded 3DELRR radar contract for second time". DefenseNews. Retrieved Aug 20, 2019.

- ^ Jaisinghani, Sagarika (2015-04-25). "Raytheon to buy cybersecurity firm Websense in $1.9 billion deal". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2020-09-22. Retrieved 2018-10-30.

- ^ Bach, James (2016-01-14). "Raytheon-Websense joint cyber venture changes name to Forcepoint". Washington Business Journal. Archived from the original on 2020-09-28. Retrieved 2018-10-31.

- ^ "Raytheon Paid $62M for Foreground Security". TransactionView. Archived from the original on 2018-10-31. Retrieved 2018-10-31.

- ^ Riley, Duncan (2016-01-14). "Raytheon|Websense acquires Stonesoft from Intel Security, renames combined company Forcepoint". SiliconANGLE. Archived from the original on 2018-10-31. Retrieved 2018-10-31.

- ^ "Rocketing around the world". The Economist. ISSN 0013-0613. Archived from the original on 2016-07-19. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ^ "Poland moves towards multi-billion-euro Patriot missile deal". Archived from the original on 2016-07-07. Retrieved 2016-07-23.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia agrees to buy $7 billion in precision munitions from U.S. firms: sources". Reuters. November 23, 2017.

- ^ "Raytheon Arm Wins $302M Deal to Boost Saudi Arabia's Defense Archived 2018-03-06 at the Wayback Machine". Nasdaq.com. December 13, 2017.

- ^ "Qatar Agrees to Buy U.S. Aircraft, Engines, Defense Equipment". Bloomberg.com. Bloomberg. 9 July 2019. Archived from the original on 10 July 2019. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- ^ a b Decker, Audrey (2024-10-16). "RTX will pay almost $1B for defrauding DOD, allegedly bribing Qatari official". Defense One. Retrieved 2024-10-16.

- ^ Judson, Jen (2020-02-21). "Raytheon completes first antenna for US Army's new missile defense radar". Defense News. Retrieved 2020-02-21.

- ^ Singer, Stephen (2019-06-09). "United Technologies says its merging with defense contractor Raytheon and moving headquarters to Boston area from Connecticut". Hartford Courant. Archived from the original on 2021-04-08. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

- ^ "2020年10月27日外交部发言人汪文斌主持例行记者会" [Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Wang Wenbin's Regular Press Conference on October 27, 2020]. Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 2020-10-26. Archived from the original on 2022-08-16. Retrieved 2022-08-16.

- ^ "中方再制裁美兩軍工企業 促停止對台軍售". Archived from the original on 2022-03-18. Retrieved 2022-05-17.

- ^ "商务部回应不可靠实体清单实施有关问题" [The Ministry of Commerce responded to questions about the implementation of the Unreliable Entity List]. Xinhua News Agency. 18 April 2023. Archived from the original on 2023-05-31. Retrieved 2023-05-30.

- ^ Moore-Carrillo, Jaime (June 20, 2023). "Raytheon rebrands as RTX". DefenseNews.com. Defense News. Retrieved June 21, 2023.

- ^ Decker, Audrey (2024-08-30). "RTX fined $200M for exporting defense tech to China, Russia, Iran". Defense One. Archived from the original on 2024-09-26. Retrieved 2024-10-17.

- ^ "Raytheon: Investors: Annual Reports". investor.raytheon.com. Retrieved 2018-11-07.

- ^ "Raytheon:Leadership". Raytheon. 20 June 2019.

- ^ Communications, Raytheon Corporate. "Raytheon News Release Archive". Archived from the original on 2018-01-14. Retrieved 2018-01-14.

- ^ "Tom Kennedy biography" (PDF). Raytheon. May 2019. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-06-20. Retrieved 2019-06-20.

- ^ "Raytheon:Investors:Board of Governance". Raytheon. May 2019. Archived from the original on 2019-06-10. Retrieved 2019-06-20.

- ^ "Raytheon Company (RTN)". Yahoo! Finance. May 1, 2015. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved April 10, 2015.

- ^ Raytheon Corporate Communications. "Raytheon". Archived from the original on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- ^ Singel, Ryan (December 19, 2007). "FBI E-Mail Shows Rift Over Warrantless Phone Record Grabs". Wired. Archived from the original on June 27, 2018.

- ^ "Raytheon targets nuclear smuggling: Firm sees profit in homeland security". BostonGlobe. 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-07.[dead link]

- ^ "Peregrine Air-to-Air Missile | Raytheon". Archived from the original on 2019-12-25. Retrieved 2019-12-25.

- ^ a b c "Is Raytheon site poisoning St. Petersburg neighborhood?". 2008-04-24. Archived from the original on 2008-04-23. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ "Raytheon's Florida Neighbors Sue Over Water Contamination". 2008-05-05. Archived from the original on 2008-05-10. Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ "Raytheon Site Summary". Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Archived from the original on 2008-10-15.

- ^ "Florida DEP". Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Archived from the original on 2008-10-15.

- ^ a b "Environmental Protection Agency". July 13, 2007. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved May 6, 2008.

- ^ Horgan, Gorreti (2006-08-19). "Irish civil rights leader Eamonn McCann arrested at occupation of Raytheon". Socialist Worker. Archived from the original on 2023-07-03. Retrieved 2023-07-03.

- ^ US EPA, OAR (2015-07-30). "2013 Climate Leadership Award Winners". www.epa.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-12-06. Retrieved 2023-07-03.

External links

[edit]- Raytheon Company website (Archived)

- Historical business data for Raytheon Company:

- SEC filings

- Raytheon Company Semiconductor Division Files Kept to Monitor the Electronics Industry, 1965–1986 (call number M0661; 11.5 linear ft.) are housed in the Department of Special Collections and University Archives at Stanford University Libraries

- Direct political contributions

- Raytheon Company

- 1922 establishments in Massachusetts

- 2020 disestablishments in Massachusetts

- 2020 mergers and acquisitions

- Collier Trophy recipients

- Aerospace companies of the United States

- American companies disestablished in 2020

- American companies established in 1922

- American entities subject to Chinese sanctions

- Companies based in Waltham, Massachusetts

- Companies formerly listed on the New York Stock Exchange

- Defunct manufacturing companies based in Massachusetts

- Defunct technology companies based in Massachusetts

- Defunct computer companies of the United States

- Defunct computer hardware companies

- Defunct computer systems companies

- Electronics companies established in 1922

- Electronics companies disestablished in 2020

- Defunct electronics companies of the United States

- Former defense companies of the United States

- Guided missile manufacturers

- Manufacturing companies disestablished in 2020

- Manufacturing companies established in 1922

- Radar manufacturers

- Superfund sites in California

- Technology companies based in the Boston area

- Technology companies disestablished in 2020

- Vacuum tubes

- Water pollution in the United States