Rationing in the United Kingdom

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Rationing was introduced temporarily by the British government several times during the 20th century, during and immediately after a war.[1][2]

At the start of the Second World War in 1939, the United Kingdom was importing 20 million long tons of food per year, including about 70% of its cheese and sugar, almost 80% of fruit and about 70% of cereals and fats. The UK also imported more than half of its meat and relied on imported feed to support its domestic meat production. The civilian population of the country was about 50 million.[3] It was one of the principal strategies of the Germans in the Battle of the Atlantic to attack shipping bound for Britain, restricting British industry and potentially starving the nation into submission.

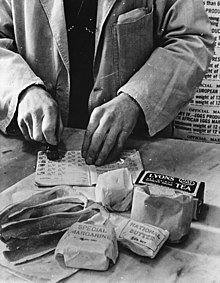

To deal with sometimes extreme shortages, the Ministry of Food instituted a system of rationing. To buy most rationed items, each person had to register at chosen shops and was provided with a ration book containing coupons. The shopkeeper was provided with enough food for registered customers. Purchasers had to present ration books when shopping so that the coupon or coupons could be cancelled as these pertained to rationed items. Rationed items had to be purchased and paid for as usual, although their price was strictly controlled by the government and many essential foodstuffs were subsidised; rationing restricted what items and what amount could be purchased as well as what they would cost. Items that were not rationed could be scarce. Prices of some unrationed items were also controlled; prices for many items not controlled were unaffordably high for most people.

During the Second World War rationing—not restricted to food—was part of a strategy including controlled prices, subsidies and government-enforced standards, with the goals of managing scarcity and prioritising the armed forces and essential services, and trying to make available to everyone an adequate and affordable supply of goods of acceptable quality.

First World War 1914–1918

In line with its business as usual policy during the First World War, the government was initially reluctant to try to control the food markets.[4] It fought off attempts to introduce minimum prices in cereal production, though relenting in the area of control of essential imports (sugar, meat, and grains). When it did introduce changes, they were limited. In 1916, it became illegal to consume more than two courses while lunching in a public eating place or more than three for dinner; fines were introduced for members of the public found feeding the pigeons or stray animals.[5]

In January 1917, Germany started unrestricted submarine warfare to try to starve Britain into submission. To meet this threat, voluntary rationing was introduced in February 1917. Bread was subsidised from September that year; prompted by local authorities taking matters into their own hands, compulsory rationing was introduced in stages between December 1917 and February 1918 as Britain's supply of wheat decreased to just six weeks' consumption.[6] To help the process, ration books were introduced in July 1918 for butter, margarine, lard, meat, and sugar.[7] Each consumer was tied to a retailer. The basic ration of sugar, butter or margarine, tea, jam, bacon and meat came to about 1,680 calories. It was adjusted for vegetarians, children and workers performing strenuous labour. Nutritional programmes for nursing mothers and young children were established by many local authorities. Unlike most of Europe bread was not rationed. It was argued that the civilian population's health improved under rationing, though tuberculosis increased.[8] During the war, average energy intake decreased by only 3%, but protein intake by 6%.[9] Controls were not fully released until 1921.

General strike of 1926

The government made preparations to ration food in 1925, in advance of an expected general strike, and appointed Food Control Officers for each region. In the event, the trade unions of the London docks organised blockades by crowds, but convoys of lorries under military escort took the heart out of the strike, so that the measures did not have to be implemented.[10]

Second World War 1939–1945

Food rationing

Emergency supplies for the 4 million people expected to be evacuated were delivered to destination centres by August 1939, and 50 million ration books were already printed and distributed.[11]

When World War II began in September 1939, petrol was the first commodity to be controlled. On 8 January 1940, bacon, butter, and sugar were rationed. Meat, tea, jam, biscuits, breakfast cereals, cheese, eggs, lard, milk, canned and dried fruit were rationed subsequently, though not all at once. In June 1942, the Combined Food Board was set up by the United Kingdom and the United States to coordinate the world supply of food to the Allies, with special attention to flows from the U.S. and Canada to Britain. Almost all foods apart from vegetables and bread were rationed by August 1942. Strict rationing created a black market. Almost all controlled items were rationed by weight; but meat was rationed by price.

Fruits and vegetables

Fresh vegetables and fruit were not rationed, but supplies were limited. Some types of imported fruit all but disappeared. Lemons and bananas became unobtainable for most of the war; oranges continued to be sold, but greengrocers customarily reserved them for children and pregnant women. Apples were available from time to time.

Many grew their own vegetables, encouraged by the "Dig for Victory" campaign. In 1942, many young children, questioned about bananas, did not believe they were real.[12] A popular music-hall song, written 20 years previously but sung ironically, was "Yes! We Have No Bananas".

Game

Game meat such as rabbit and pigeon was not rationed. Some British biologists ate laboratory rats.[13][14][15][16][17][18]

Bread

Bread was not rationed until after the war ended, but the "national loaf" of wholemeal bread replaced the white variety. It was found to be mushy, grey and easy to blame for digestion problems.[19] There were four permitted loaves and slicing and wrapping were not permitted.[11]

Fish

Fish was not rationed, but prices increased considerably as the war progressed. The government did not ration fish, because fishermen, at risk from enemy attack and mines, had to be paid a premium for their catch in order to fish at all. Prices were controlled from 1941.[20][page needed] Like other foods, fish was seldom available in abundance. During the war, the Royal Navy requisitioned hundreds of trawlers for military use, leaving primarily smaller vessels thought less likely to be targeted by Axis forces to fish. Supplies eventually dropped to 30% of pre-war levels.[20] Wartime fish and chips was often felt to be below standard because of the low-quality fat available for frying.[citation needed]

Honey

Due to the vital role beekeeping played in British agriculture and industry, special allotments of sugar were allowed for each hive.[21] In 1943, the Ministry of Food announced that beekeepers would qualify for supplies of sugar not exceeding ten pounds per colony to keep their beehives going through the winter, and five pounds for spring feeding. Honey was not rationed, but its price was controlled - as with other unrationed, domestically produced produce, sellers imposed their own restrictions.

Alcohol

All drinks except beer were scarce. Beer was considered a vital foodstuff as it was a morale booster. Brewers were short of labour and suffered from the scarcity of imported barley.[22] A ban on importing sugar for brewing and racking made beer strengths weaker.[23][failed verification]

Fuel

On 13 March 1942 the abolition of the basic petrol ration was announced, effective from the 1 July[24]: 249 (Ivor Novello, a prominent British public figure in the entertainment industry, was sent to prison for four weeks for misusing petrol coupons).[24]: 249–250 Thenceforth, vehicle fuel was only available to official users, such as the emergency services, bus companies and farmers. The priority users of fuel were always the armed forces.[original research?] Fuel supplied to approved users was dyed, and use of this fuel for non-essential purposes was an offence.

Subsidies

In addition to rationing and price controls, the government equalised the food supply through subsidies on items consumed by the poor and the working class. In 1942–43, £145 million was spent on food subsidies, including £35 million on bread, flour and oatmeal, £23 million on meat and the same on potatoes, £11 million on milk, and £13 million on eggs.[25]

Restaurants

Restaurants were initially exempt from rationing but this was resented because of the public perception that "luxury" off-ration foodstuffs were being unfairly obtained by those who could afford to dine regularly in restaurants.[26] In May 1942, the Ministry of Food issued new restrictions on restaurants:[27]

- Meals were limited to three courses; only one component dish could contain fish or game or poultry (but not more than one of these)

- In general, no meals could be served between 11:00 p.m. and 5:00 a.m. without a special licence

- The maximum price of a meal was 5 shillings (equivalent to £15 in 2023). Extra charges allowed for cabaret shows and luxury hotels.

Public catering

About 2,000 new wartime establishments called British Restaurants were run by local authorities in schools and church halls. Here, a plain three-course meal cost only 9d (equivalent to £2.21 in 2023) and no ration coupons were required. They evolved from the London County Council's Londoners' Meals Service, which began as an emergency system for feeding people who had had their houses bombed and could no longer live in them. They were open to all and mostly served office and industrial workers.[28][29]

Cooking depots were set up in Sheffield and Plymouth, providing roast dinners, stew and pudding. Hot sweet tea was often distributed after bombing raids.[30]

Health effects

In December 1939, Elsie Widdowson and Robert McCance of the University of Cambridge tested whether the United Kingdom could survive with only domestic food production if U-boats ended all imports. Using 1938 food production data, they fed themselves and other volunteers one egg, one pound (450 g) of meat and four ounces (110 g) of fish a week; one-quarter imperial pint (140 mL) of milk a day; four ounces (110 g) of margarine; and unlimited amounts of potatoes, vegetables and wholemeal bread. Two weeks of intensive outdoor exercise simulated the strenuous wartime physical work Britons would likely have to perform. The scientists found that the subjects' health and performance remained very good after three months; the only negative results were the increased time needed for meals to consume the necessary calories from bread and potatoes, and what they described as a "remarkable" increase in flatulence from the large amount of starch in the diet. The scientists also noted that their faeces had increased by 250% in volume.[31]

The results – kept secret until after the war – gave the government confidence that, if necessary, food could be distributed equally to all, including high-value war workers, without causing widespread health problems. Britons' actual wartime diet was never as severe as in the Cambridge study because imports from the United States avoided the U-boats,[31] but rationing improved the health of British people; infant mortality declined and life expectancy rose, excluding deaths caused by hostilities. This was because it ensured that everyone had access to a varied diet with enough vitamins.[29][32] Blackcurrant syrup and later American bottled orange juice was provided free for children under 2, and those under 5 and expectant mothers got subsidised milk. Consumption of fat and sugar declined while consumption of milk and fibre increased.[33]

Standard food rationing during the Second World War

The standard rations during the Second World War were as follows. Quantities are per week unless otherwise stated.[34]

Food rations

| Item | Maximum level | Minimum level | April 1945 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bacon and ham | 8 oz (227 g) | 4 oz (113 g) | 4 oz (113 g) |

| Sugar | 16 oz (454 g) | 8 oz (227 g) | 8 oz (227 g) |

| Loose tea | 4 oz (113 g) | 2 oz (57 g) | 2 oz (57 g) |

| Meat | 1 s. 2d. | 1s | 1s. 2d. (equivalent to £3.18 in 2023[35]) |

| Cheese | 8 oz (227 g) | 1 oz (28 g) | 2 oz (57 g)

Vegetarians were allowed an extra 3 oz (85 g) cheese[36] |

| Preserves | 1 lb (0.45 kg) per month 2 lb (0.91 kg) marmalade |

8 oz (227 g) per month | 2 lb (0.91 kg) marmalade or 1 lb (0.45 kg) preserve or 1 lb (0.45 kg) sugar |

| Butter | 8 oz (227 g) | 2 oz (57 g) | 2 oz (57 g) |

| Margarine | 12 oz (340 g) | 4 oz (113 g) | 4 oz (113 g) |

| Lard | 3 oz (85 g) | 2 oz (57 g) | 2 oz (57 g) |

| Sweets | 16 oz (454 g) per month | 8 oz (227 g) per month | 12 oz (340 g) per month |

Army and Merchant Navy rations

| Item | Army Rations Home Service Scale | Seamen on weekly articles | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | ||

| Meat | 5 lb 4 oz (2.4 kg) | 2 lb 10 oz (1.2 kg) | 2 lb 3 oz (0.99 kg) |

| Bacon and ham (uncooked, free of bone) |

8 oz (230 g) | 9 oz (260 g) | 8 oz (230 g) |

| Butter and margarine | 13+1⁄4 oz (380 g) (in any proportions of butter and margarine) | 10+1⁄2 oz (300 g) (margarine only) | 10+1⁄2 oz (300 g) (not more than 3+1⁄2 oz (99 g) butter) |

| Cheese | 4 oz (110 g) | 4 oz (110 g) | 4 oz (110 g) |

| Cooking fats | 2 oz (57 g) (may be taken in the form of margarine) | – | – |

| Sugar | 1 lb 14 oz (850 g) | 14 oz (400 g) | 14 oz (400 g) |

| Tea | 4 oz (110 g) | 2 oz (57 g) | 2 oz (57 g) |

| Preserves |

|

7 oz (200 g) (jam, marmalade, syrup) |

10+1⁄2 oz (300 g) (jam, marmalade, syrup) |

1s 2d bought about 1 lb 3 oz (540 g) of meat. Offal and sausages were rationed only from 1942 to 1944. When sausages were not rationed, the meat needed to make them was so scarce that they often contained a high proportion of bread. Eggs were rationed and "allocated to ordinary [citizens] as available"; in 1944 thirty allocations of one egg each were made. Children and some invalids were allowed three a week; expectant mothers two on each allocation.

- 1 egg per week or 1 packet (makes 12 ersatz eggs) of egg powder per month (vegetarians were allowed two eggs)

- plus, 24 points for four weeks for tinned and dried food.

Arrangements were made for vegetarians so that other goods were substituted for their rations of meat.[36]

Milk was supplied at 3 imperial pints (1.7 litres) each week with priority for expectant mothers and children under 5; 3.5 imp pt (2.0 L) for those under 18; children unable to attend school 5 imp pt (2.8 L), certain invalids up to 14 imp pt (8.0 L). Each person received one tin of milk powder (equivalent to 8 imperial pints or 4.5 litres) every eight weeks.[39]

Special civilian rations

Persons falling within the following descriptions were allowed 8 oz (230 g) of cheese a week in place of the general ration of 3 oz (85 g):

- vegetarians (meat and bacon coupons must be surrendered)

- underground mine workers

- agricultural workers holding unemployment insurance books or cards bearing stamps marked "Agriculture"

- county roadmen

- forestry workers (including fellers and hauliers)

- land drainage workers (including Catchment Board workers)

- members of the Auxiliary Force of the Women's Land Army[38]

- railway train crews (including crews of shunting engines but not including dining car staffs)

- railway signalmen and permanent way men who have no access to canteen facilities

- certain types of agricultural industry workers (workers employed on threshing machines, tractor workers who are not included in the Agricultural Unemployment Insurance Stamp Scheme, hay pressers and trussers).

Weekly supplementary allowances of rationed foods for invalids

| Disease | Food supplementary allowance |

Quantity | Coupons to be surrendered |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | Butter and margarine | 12 oz (340 g) (not more than 4 oz (110 g) butter) | Sugar |

| Diabetes | Meat | 2s. 4d. adult, 1s. 2d. child under six | Sugar |

| Diabetes – vegetarians only | Cheese | 8 oz (230 g) | Sugar |

| Hypoglycaemia | Sugar | 16 oz (450 g) | – |

| Steatorrhoea | Meat | 4s. 8d. adult, 2s. 4d. child under six | Butter and margarine |

| Nephritis with gross albuminuria and gross oedema, also nephrosis |

Meat | 3s. 6d. adult, 1s. 9d. child under six |

Non-food rations

Clothing

As the war progressed, rationing was extended to other consumable commodities including clothing, which was controlled on a system of points allocated to different garments.

Following the depletion of raw materials and redirection of labour towards wartime manufactures (such as uniforms),[40] alongside rising inflation, and the inclusion of purchase tax on clothing in October 1940, prices of garments and textiles increased.[41] As a result, civilian access to clothing was tightening. Government regulation was required in order to ensure the ability to buy clothing was maintained across the civilian population.[41]

The rationing of cloth, clothing, and footwear was introduced in June 1941, and remained in place until March 1949. Clothes rationing also aimed to restrict the amount of new clothes the public could buy,[42] and therefore reduce the amount of clothing produced for civilians.[40]

Reported in local and national newspapers, clothes rationing came as a surprise to the public, in order to avoid panic-buying.[43] Coupons were to be presented on purchase of clothing, shoes, and fabrics alongside cash payment.[43] Until the issuing of Clothing Coupon books for 1942-43, consumers were to surrender unused margarine coupons from their food ration coupon book when buying clothing.[44] Initially people were allocated 66 points for clothing per year; in 1942, this was cut to 48, in 1943 to 36, and in 1945–1946 to 24.[45]

Different types of clothes were ascribed different coupon values, determined by how much material and labour went into each item's manufacture. For example, an adult's skirt would require seven coupons and a pair of child's pyjamas six coupons.[41] As well as being used for clothing, coupons could be used for wool, cotton and household textiles. Clothing sized for children under the age of four did not require coupons for purchase.[41]

The prices of second-hand clothing and fur coats were fixed, but no coupons were required to buy them. People were allocated extra coupons for work clothes, such as overalls for factory work.[46] Manual workers, civilian uniform wearers, diplomats, performers and new mothers also received extra coupons.

Garments of the same description but different quality would have different prices but require the same number of coupons; the more affordable clothing would often be less robust and wear out sooner, even with repair.[45] This, therefore, led the Government to implement the Utility Clothing Scheme in September 1941, which was introduced alongside other measures, such as the civilian population being encouraged to repair and remake old clothes; pamphlets were produced by the Ministry of Information with the slogan "Make Do and Mend" in 1943 which gave ideas and instruction as part of a larger campaign which was put in place through collaboration with voluntary organisations.[47][48]

Clothes rationing ended on 15 March 1949.

Soap

All types of soap were rationed. Coupons were allotted by weight or (if liquid) by quantity. In 1945, the ration gave four coupons each month; babies and some workers and invalids were allowed more.[49] A coupon would yield:

- 4 oz (113 g) bar hard soap

- 3 oz (85 g) bar toilet soap

- 1⁄2 oz (14 g) No. 1 liquid soap

- 6 oz (170 g) soft soap

- 3 oz (85 g) soap flakes

- 6 oz (170 g) powdered soap

Fuel

The Fuel and Lighting (Coal) Order 1941 came into force in January 1942. Central heating was prohibited in the summer months.[49] Domestic coal was rationed to 15 long hundredweight (1,680 lb; 762.0 kg) for those in London and the south of England; 20 long hundredweight (2,240 lb; 1,016 kg) for the rest (the southern part of England having generally a milder climate).[49] Some kinds of coal such as anthracite were not rationed, and in coal-mining areas waste coal was eagerly gathered, as it had been in the Great Depression.

Petrol

Petrol rationing was introduced in September 1939 with an allowance of approximately 200 miles (320 kilometres) of motoring per month. The coupons issued related to a car's calculated RAC horsepower and that horsepower's nominal fuel consumption. From July 1942 until June 1945, the basic ration was suspended completely, with essential-user coupons being issued only to those with official sanction. In June 1945, the basic ration was restored to allow about 150 miles (240 km) per month; this was increased in August 1945 to allow about 180 miles (290 km) per month.[50]

Paper

Newspapers were limited from September 1939, at first to 60% of their pre-war consumption of newsprint. Paper supply came under the No 48 Paper Control Order, 4 September 1942, and was controlled by the Ministry of Production. By 1945, newspapers were limited to 25% of their pre-war consumption. Wrapping paper for most goods was prohibited.[51]

The paper shortage often made it more difficult than usual for authors to get work published. In 1944, George Orwell wrote:

In Mr Stanley Unwin's recent pamphlet Publishing in Peace and War, some interesting facts are given about the quantities of paper allotted by the Government for various purposes. Here are the present figures:

Newspapers 250,000 tons H.M. Stationery Office 100,000 tons Periodicals (nearly) 50,000 tons Books 22,000 tons A particularly interesting detail is that out of the 100,000 tons allotted to the Stationery Office, the War Office gets no less than 25,000 tons, or more than the whole of the book trade put together. ... At the same time paper for books is so short that even the most hackneyed "classic" is liable to be out of print, many schools are short of textbooks, new writers get no chance to start and even established writers have to expect a gap of a year or two years between finishing a book and seeing it published.

Other products

Whether rationed or not, many personal-use goods became difficult to obtain because of the shortage of components. Examples included razor blades, baby bottles, alarm clocks, frying pans and pots. Balloons and sugar for cakes for birthday parties were partially or completely unavailable. Couples had to use a mock cardboard and plaster wedding cake in lieu of a real tiered wedding cake, with a smaller cake hidden in the mock cake. Houseplants were impossible to get and people used carrot tops instead.[53] Many fathers saved bits of wood to build toys for Christmas presents,[54] and Christmas trees were almost impossible to obtain due to timber rationing.[55]

Post-Second World War 1945–1954

On 8 May 1945, the Second World War ended in Europe, but rationing continued for several years afterwards. Some aspects of rationing became stricter than they were during the war. Bread was rationed from 21 July 1946 to 24 July 1948. Average body weight fell and potato consumption increased. Certain foodstuffs that the average 1940s British citizen would find unusual, for example whale meat and canned snoek fish from South Africa, were not rationed. Despite this, they did not prove popular. In 1950, 4000 tonnes of whale meat went unsold on Tyneside.[2][56][page needed]

When sweets were taken off ration in April 1949 (but sugar was still rationed), there was, understandably, a rush on sweetshops, and rationing had to be reintroduced in August, remaining until 1953.[30] At the time, this was presented as necessary to feed people in European areas under British control, whose economies had been devastated by the fighting.[2] This was partly true, but with many British men still mobilised in the armed forces, an austere economic climate, a centrally-planned economy under the post-war Labour government and the curtailment of American assistance (in particular, the closure of the Combined Food Board in 1946), resources were not available to expand food production and food imports. Frequent strikes by some workers (most critically dock workers) made things worse.[2]

A common ration book fraud was the ration books of the dead being kept and used by the living.[24]: 264

Political reaction

In the late 1940s, the Conservative Party used and encouraged growing public anger at rationing, scarcity, controls, austerity and government bureaucracy to rally middle-class supporters and build a political comeback that won the 1951 general election. Their appeal was especially effective to housewives, who faced more difficult shopping conditions after the war than during it.[57]

Timeline

1945

- 27 May: Bacon ration cut from 4 to 3 ounces (113 to 85 g) per week. Cooking fat ration cut from 2 to 1 ounce (57 to 28 g) per week. Soap ration cut by an eighth, except for babies and young children.[58] The referenced newspaper article predicted that households would be grossly hampered in making food items that included pastry.

- 1 June: The basic petrol ration for civilians was restored.[24]: 253 [50]

- 19 July: In order to preserve the egalitarian nature of rationing, gift food parcels from overseas weighing more than 5 lb (2.3 kg) would be deducted from the recipient's ration.

1946

- Summer: Continual rain ruined Britain's wheat crop. Bread and flour rationing started.

1947

- January–March: Winter of 1946–1947 in the United Kingdom: long hard frost and deep snow. Frost destroyed a huge amount of stored potatoes. Potato rationing started.

- Mid-year: A transport and dock strike, which among other effects caused much loss of imported meat left to rot on the docks, until the Army broke the strike. The basic petrol ration was stopped.[24]: 253 [50]

1948

- 1 June: The Motor Spirit (Regulation) Act 1948 was passed,[59] ordering a red dye to be to put into some petrol, and that red petrol was only allowed to be used in commercial vehicles. A private car driver could lose their driving licence for a year if red petrol was found in their car. A petrol station could be shut down if it sold red petrol to a private car driver.

- June: The basic petrol ration was restored, but only allowed about 90 miles per month.[50]

- Bread came off ration.

1949

- May 1949: Clothes rationing ended. According to one author,[24]: 273 this was because attempts to enforce it were defeated by continual massive illegality (black market, unofficial trade in loose clothing coupons (many forged), bulk thefts of unissued clothes ration books).

- June, July and August 1949: The basic petrol ration was temporarily increased to allow about 180 miles per month.[50]

1950

- 23 February 1950: 1950 general election fought largely on the issue of rationing. The Conservative Party campaigned on a manifesto of ending rationing as quickly as possible.[2] The Labour Party argued for the continuation of rationing indefinitely. Labour was returned, but with its majority badly slashed to 5 seats.

- March 1950: The Ministry of Fuel and Power announced that the petrol ration would again be doubled for the months of June, July and August.[50]

- April 1950: The Ministry of Fuel and Power announced that the petrol ration would be doubled for 12 months from 1 June.[50]

- 26 May 1950: Petrol rationing ended.[60]

1951

- 25 October 1951: 1951 United Kingdom general election. The Conservatives came back into power.

1953

- 4 February 1953: Confectionery (sweets and chocolate) rationing ended.[61][62][63]

- September 1953: Sugar rationing ended.

1954

- 4 July 1954: Meat and all other food rationing ended in Britain.[64]

Although rationing formally ended in 1954, cheese production was affected for decades afterwards. During rationing, most milk in Britain was used to make one kind of cheese, nicknamed Government Cheddar (not to be confused with the government cheese issued by the US welfare system).[65] This wiped out nearly all other cheese production in the country, and some indigenous varieties of cheese almost disappeared.[65] Later government controls on milk prices through the Milk Marketing Board continued to discourage production of other varieties of cheese until well into the 1980s,[66] and it was only in the mid-1990s (following the effective abolition of the MMB) that the revival of the British cheese industry began in earnest.

1958

- Coal rationing ends in July.[67]

Suez Crisis 1956–1957

During the Suez Crisis, petrol rationing was briefly reintroduced and ran from 17 December 1956[68] until 14 May 1957.[69] Advertising of petrol on the recently introduced ITV was banned for a period.

Oil crises of 1973 and 1979

Petrol coupons were issued for a short time as preparation for the possibility of petrol rationing during the 1973 oil crisis.[70] The rationing never came about, in large part because increasing North Sea oil production allowed the UK to offset much of the lost imports. By the time of the 1979 energy crisis, the United Kingdom had become a net exporter of oil, so on that occasion the government did not even have to consider petrol rationing.

See also

- British cuisine

- List of renewable resources produced and traded by the United Kingdom

- Ration stamp

- Reichsnährstand

- Spiv

- Utility clothing

- Utility furniture

- Woolton pie

- Gull eggs § British Isles

References

- ^ Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina (2002), Austerity in Britain: Rationing, Controls and Consumption, 1939–1955, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-925102-5

- ^ a b c d e Kynaston, David (2007), Austerity Britain, 1945–1951, Bloomsbury, ISBN 978-0-7475-7985-4

- ^ Macrory, Ian (2010). Annual Abstract of Statistics (PDF) (2010 ed.). Office for National Statistics. p. 29. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ Hurwitz, Samuel J. (2013). State Intervention in Great Britain: Study of Economic Control and Social Response, 1914–1919. Routledge. pp. 12–29. ISBN 978-1-136-93186-4.

- ^ Ian Beckett, The Home Front 1914–1918: How Britain Survived the Great War (2006) p. 381

- ^ John Morrow, The Great War: An Imperial History (2005) p. 202

- ^ Alan Warwick Palmer and Veronica Palmer, The chronology of British history (1992) pp. 355–356

- ^ Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a large planet. US: University of Chicago Press. pp. 152–3. ISBN 978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^ Beckett, The Home Front 1914–1918 pp. 380–382

- ^ Hancock, William Keith; Gowing, Margaret (1975). British War Economy. History of the Second World War. Vol. 1 (rev. ed.). Her Majesty's Stationery Office. p. 52. OCLC 874487495.

- ^ a b Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a large planet. US: University of Chicago Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^ Reagan, Geoffrey. Military Anecdotes (1992) pp. 19 & 20. Guinness Publishing ISBN 0-85112-519-0

- ^ Jared M. Diamond (January 2006). Collapse: How Societies Choose to Fail Or Succeed. Penguin. pp. 105–. ISBN 978-0-14-303655-5.

- ^ David E. Lorey (2003). Global Environmental Challenges of the Twenty-first Century: Resources, Consumption, and Sustainable Solutions. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 210–. ISBN 978-0-8420-5049-4.

- ^ David G. McComb (1997). Annual Editions: World History. McGraw-Hill Higher Education. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-697-39293-0.

- ^ Peacock, Kent Alan (1996). Living with the earth: an introduction to environmental philosophy. Harcourt Brace Canada. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7747-3377-9.

- ^ Spears, Deanne (2003). Improving Reading Skills: Contemporary Readings for College Students. McGraw-Hill. p. 463. ISBN 978-0-07-283070-5.

- ^ Sovereignty, Colonialism and the Indigenous Nations: A Reader. Carolina Academic Press. 2005. p. 772. ISBN 978-0-89089-333-3.

- ^ Calder, Angus (1992). The people's war: Britain 1939–45 (New ed.). Pimlico. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-0-7126-5284-1.

- ^ a b Fisheries in War Time: Report on the Sea Fisheries of England and Wales by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries for the Years 1939–1944 Inclusive. H.M. Stationery Office. 1946.

- ^ "Beekeeping in Swindon during WWII". BBC Wiltshire. 5 August 2009. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ "Beer Goes to War". All About Beer. September 2002. Archived from the original on 2 October 2019. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ morningadvertiser.co.uk (12 February 2019). "How the pub survived the World Wars". morningadvertiser.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Nicol, Patricia (2010). Sucking Eggs. London: Vintage Books. ISBN 9780099521129.

- ^ Keesing's Contemporary Archives. Vol. IV–V. June 1943. p. 5,805.

- ^ "British food control". Army News. Darwin, Australia: Trove. 14 May 1942. Archived from the original on 16 June 2024. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Keesing's Contemporary Archives. Vol. IV. June 1942. p. 5,224.

- ^ Home Front Handbook, p. 78.

- ^ a b Creaton, Heather J. (1998). "5. Fair Shares: Rationing and Shortages". Sources for the History of London 1939–45: Rationing. British Records Association. pp. 85–86. ISBN 978-0-900222-12-2. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ^ a b Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a large planet. US: University of Chicago Press. p. 164. ISBN 978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^ a b Dawes, Laura (24 September 2013). "Fighting fit: how dietitians tested if Britain would be starved into defeat". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ^ "Wartime rationing helped the British get healthier than they had ever been". Medical News Today. 21 June 2004. Archived from the original on 16 April 2019. Retrieved 20 January 2013.

- ^ Otter, Chris (2020). Diet for a large planet. US: University of Chicago Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-226-69710-9.

- ^ Home Front Handbook, pp. 46–47.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b Courtney, Tina (April 1992). "Veggies at war". The Vegetarian. Vegetarian Society. Archived from the original on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 19 July 2009.

- ^ Home Front Handbook, p. 46.

- ^ Home Front Handbook, p. 47.

- ^ a b "8 Facts about Clothes Rationing in Britain During the Second World War". Imperial War Museums. Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d Shrimpton, Jayne (2014). Fashion in the 1940s (1st ed.). Oxford: Bloomsbury Publishing PLC. pp. 19–21. ISBN 978-0-74781-353-8.

- ^ "How Clothes Rationing Affected Fashion In The Second World War". Imperial War Museums. Archived from the original on 30 June 2023. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ a b Howell, Geraldine (2013). Wartime Fashion: From Haute Couture to Homemade, 1939–1945 (2nd ed.). London: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-8578-5071-3.

- ^ Summers, Julie (2015). Fashion on the Ration: Style in the Second World War (1st ed.). London: Profile Books LTD. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-78125-326-7.

- ^ a b "8 Facts about Clothes Rationing in Britain During the Second World War". Imperial War Museums. n.d. Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ Home Front Handbook, pp. 47–48.

- ^ Clouting, Laura (11 January 2018). "10 Top Tips for Winning at Make Do and Mend". Imperial War Museum. Archived from the original on 23 May 2023. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ "Make Do and Mend – 1943". British Library. Archived from the original on 13 May 2020. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Home Front Handbook, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The World of Motoring – The End of Rationing". The Motor. London: Temple Press Ltd: 564. 7 June 1950.

- ^ Home Front Handbook, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Orwell, George (20 October 1944). "As I Please". Tribune. Archived from the original on 25 July 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2021.

- ^ "Creative solutions to shortages in and after World War Two". Join me in the 1900s: a social history of everyday life. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.[self-published source]

- ^ Mackay, Robert (2002). Half the Battle: Civilian Morale in Britain during the Second World War. Manchester University Press. pp. 112–113. ISBN 0-7190-5893-7.

- ^ Webley, Nicholas (2003). A Taste of Wartime Britain. Thorogood. p. 36. ISBN 1-85418-213-7.

- ^ Patten, Marguerite (2005). Feeding the Nation. Hamlyn. ISBN 978-0-600-61472-2.

- ^ Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska, "Rationing, austerity and the Conservative party recovery after 1945", Historical Journal (1994) 37#1 pp. 173–197

- ^ The Daily Telegraph 23 May 1945, reprinted on p. 34 of Daily Telegraph Saturday 23 May 2015

- ^ Mills, T. O. (1949). "22 Police Journal 1949 Motor Spirit (Regulation) Act, 1948, The". Police Journal. 22: 280. doi:10.1177/0032258X4902200407. S2CID 152130437. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "1950: UK drivers cheer end of fuel rations". BBC News. 26 May 1950. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ^ "Ration and price control of chocolates and sweets ends as from to-day, the Food Minister told the House of Commons this afternoon." Sweets are now off-ration. Aberdeen, Scotland: Evening Express. 4 February 1953. P. 1, col. 5.

- ^ "Immediately after the surprise announcement yesterday by the Minister of Food that sweets rationing "will end today", an Evening News reporter went out to buy himself half-pound box of chocolates." Sweets. All you want, and no bother. Shields Daily News. Thursday, 5 February 1953. Page 4, col. 4.

- ^ From Our Political Correspondent : "Answering questions by Sir Ian Fraser (C. Morecambe and Lonsdale) and Mr Kenneth Thompson (C. Walton) the Minister of Food announced that the rationing and price control of chocolate and sugar confectionary ends to-day." Sweets off the ration. Liverpool, England. Liverpool Echo. Wednesday, 04 February 1953. P. 6.

- ^ "1954: Housewives celebrate end of rationing". BBC. 4 July 1954. Archived from the original on 7 March 2008. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ a b "Government Cheddar Cheese". CooksInfo.com. Archived from the original on 15 February 2021. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ Potter, Mich (9 October 2007). "Cool Britannia rules the whey". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 13 July 2011.

- ^ "End of coal rationing announced". www.information-britain.co.uk. Archived from the original on 13 September 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ^ "Motorists rationed to 200 miles a month". Birmingham Gazette. 21 November 1956. p. 1. Retrieved 30 November 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "1957: Cheers as petrol rationing ended". BBC News. London: BBC. 14 May 1957. Archived from the original on 18 May 2008. Retrieved 27 March 2009.

- ^ "Motor fuel ration books 1973". The memory box project. Wessex Heritage Trust. Archived from the original on 25 January 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2022.

Sources

- Home Front Handbook. Imperial War Museum (Ministry of Information). 2005 [1945]. ISBN 1-904897-11-8.

Further reading

- Beckett, Ian F.W. The Home Front 1914–1918: How Britain Survived the Great War (2006).

- Hammond, R.J. Food and agriculture in Britain, 1939–45: Aspects of wartime control (Food, agriculture, and World War II) (Stanford U.P. 1954); summary of his three volume official history entitled Food (1951–53)

- Knight, Katherine (2007). Spuds, Spam and Eating for Victory: Rationing in the Second World War. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5946-2.

- Sitwell, William (2016). Eggs or Anarchy? The Remarkable Story of the Man Tasked with the Impossible: To Feed a Nation at War. London: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4711-5105-7.

- Smith, Daniel (2011). The Spade as Mighty as the Sword: The Story of World War Two's Dig for Victory Campaign. Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-617-8.

- Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina. Austerity in Britain: Rationing, Controls & Consumption, 1939–1955 (2000) 286 pp. online

- Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina. "Rationing, austerity and the Conservative party recovery after 1945", Historical Journal (1994) 37#1 pp. 173–197 in JSTOR