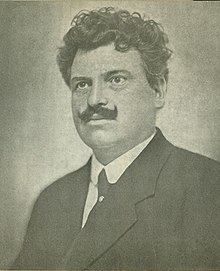

Aleksandar Stamboliyski

Aleksandar Stamboliyski | |

|---|---|

| |

| 20th Prime Minister of Bulgaria | |

| In office 14 October 1919 – 9 June 1923 | |

| Monarch | Boris III |

| Preceded by | Teodor Teodorov |

| Succeeded by | Aleksandar Tsankov |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Aleksandar Stoimenov Stamboliyski 1 March 1879 Slavovitsa, Eastern Rumelia, Ottoman Empire (now Bulgaria) |

| Died | 14 June 1923 (aged 44) Slavovitsa, Bulgaria |

| Manner of death | Assassination |

| Political party | Bulgarian Agrarian National Union |

| Spouse |

Milena Daskalova (m. 1900) |

| Children | Nadezhda Asen |

| Education | University of Munich |

| Signature |  |

Aleksandar Stoimenov Stamboliyski (Bulgarian: Александър Стоименов Стамболийски;[a] 1 March 1879 – 14 June 1923) was a Bulgarian politician who served as the Prime Minister of Bulgaria from 1919 until 1923.

Stamboliyski was a member of the Agrarian Union, an agrarian peasant movement which was not allied to the monarchy, and edited their newspaper. He opposed the country's participation in World War I and its support for the Central Powers. In a famous incident during 1914 Stamboliyski's patriotism was challenged when members of the Bulgarian parliament questioned whether he was Bulgarian or not, to which he shouted in response "At a moment, like the current, when our brothers South Slavs are threatened, I am neither a Bulgarian nor a Serb, I am a South Slav!".[1] This statement relates to his belief in a Balkan Federation which would unite the region and supersede many of the national identities which existed at the time.[citation needed] He was court-martialed and sentenced to life in prison in 1915 due to his opposition to Bulgaria joining the Central Powers in WWI.

In 1918, with the defeat of Bulgaria as an ally of the Central Powers, Tsar Ferdinand abdicated in favor of his son Tsar Boris III who released Stamboliyski from prison. He joined the government in January 1919, and was appointed prime minister on October 14 of that year. On March 20, 1920, the Agrarian Union won national elections and Stamboliyski was confirmed as prime minister.

During his term in office, Stamboliyski made a concerted effort to improve relations with the rest of Europe. This resulted in Bulgaria becoming the first of the defeated states to join the League of Nations in 1920.[2] Though popular with the peasants, he antagonized the middle class and military. He was ousted in a military coup in June 1923. He attempted to raise a rebellion against the new government, but was captured by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, which detested him for renouncing Bulgarian national interest on the region of Macedonia, was brutally tortured, and killed.

Born to a farmer, Aleksandar Stamboliyski spent his childhood in his birth village of Slavovitsa, the same village where he would later gather several thousand insurrectionists from the region and advance against the town of Pazardzhik. However, before this grand counter-insurgence was to transpire, Stamboliyski had to work himself up the ranks of the nation's political scene as the leader of the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union. Although successful in his political ambition of acquiring the highest political office of the state, the unstable political atmosphere of Bulgaria in the early inter-war years ultimately contributed to Stamboliyski's demise.

Early political career

[edit]This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2007) |

Until the mid 20th century Bulgaria was primarily a land of small, independent peasant farmers. The proportion of the population (approximately 4/5) who were peasants was roughly the same in 1920 as it had been in 1878.[3] The Bulgarian Agrarian National Union, or BANU, emerged in 1899 in reaction to the low standard of living facing the agrarian peasants of Bulgaria as well as the general focus on the towns and cities which marked the political situation at the turn of the twentieth century. By 1911, as the leader of the BANU, Stamboliyski was a notorious anti-monarchist and led the opposition to Tsar Ferdinand of Bulgaria. On September 25, 1918, in order to gain the BANU's acceptance, the regime was forced to release a number of political detainees, most notably Aleksandar Stamboliyski, who had been sentenced to life in prison after his meeting with Tsar Ferdinand to protest the war effort on 18 September 1915; two weeks before Bulgaria entered World War I on the side of the Central Powers. When the regime released Stamboliyski from prison, it did so with the hope that he would contain the growing unrest within the army, which at that time was essentially in full rebellion and heading for Sofia. While he initially tried to quell the rebellion, his fellow agrarian party activist Rayko Daskalov, who had been sent with Stamboliyski for the same purpose, quickly joined the rebellion and became its de facto leader. Rayko Daskalov issued a declaration under his name and that of Stamboliyski, which named Bulgaria a people's republic and the monarchy of Tsar Ferdinand was denounced and told to surrender to the new provisional government headed on paper by the BANU leader. Even though Stambolyiski had not been informed of Daskalov's decision (his name had been added to the declaration without his knowledge) and he immediately went to Sofia to inform the government that he did not support the uprising, a warrant was issued for his arrest.[4]

Radomir Rebellion (1918)

[edit]The rebellion, centered to the west of Sofia in the town of Radomir threatened to develop into a national revolution, but the movement for a new, agrarian republic was quickly eliminated due to several factors and was left without the sufficient means to bring about the change it desired. Lasting only from 28 September until 2 October, the rebellion, although short-lived, found some early success. The mutineers managed to enter Bulgaria's capital where Tsarist forces, led by general Aleksandar Protogerov, crushed the rebellion killing an estimated 2,000 soldiers and arresting an estimated 3,000. Unlike many of his supporters, Stamboliyski was able to escape the fate of imprisonment or execution and, instead, went into hiding until he was to re-surface in the political arena during the reign of Tsar Boris III. The movement, however, could not be considered a total failure by the Agrarian Union as it was successful in eliminating the rule of Tsar Ferdinand, who fled Bulgaria by train on 3 October 1918. Ferdinand was to be succeeded by his son, Boris III, with the approval of the Allied Powers.

Ascension to power

[edit]

After Tsar Boris III took the throne, the emerging political factions in Bulgaria were the Agrarians, the Socialists, and the Macedonian irredentists. However, due to the loss of the territory of Macedonia immediately following Bulgaria's surrender to the Allied forces, the Macedonian faction fell out of contention leaving the Agrarian and Communist factions struggling for political supremacy. As the general election of 1919 approached, Stamboliyski came out of hiding and won the election of prime minister of the new coalition cabinet. However, because the election was so close, Stamboliyski was forced to form a government coalition between the agrarians and the left-wing parliamentary parties. By March 1920, however, Stamboliyski was able to form a solely BANU government with another decisive election victory and some tactical manipulation of the parliamentary system (common practice at the time). From his complete acquisition of power in March 1920, until his death on 14 June 1923, Stamboliyski ruled Bulgaria with a strong personality leading many to remember him as a kind of strongman, dictator, or thug. This is in spite of his electoral successes.[citation needed]

Rule of Stamboliyski

[edit]

Stamboliyski's government immediately faced pressures from the political left and right, a harsh international occupation force, debt amounting to a “preposterous sum”,[5] as well as national problems such as food shortages, general strikes, and a great flu epidemic. His goal was to transform the political, economic, and social structures of the state while at the same time rejecting the rhetoric of radicalism and its Bolshevik associations. He aimed at establishing the rule of the peasant, which comprised over 80% of the population of Bulgaria in 1920.[6] Part of his objective was to offer each member of the dominant group an equitable distribution of property and access to the cultural and welfare facilities in all villages. The local BANU cooperative organizations known as the Zemedelski Druzhbi (Agrarian fellowships) were to play a vital role in linking the peasant economy to the national and international markets in addition to offering the benefits of large scale agriculture without resorting to Soviet style collectivization. Stamboliyski founded the BANU Orange Guard, a peasant militia that both protected him and carried out his agrarian reforms. In foreign policy, Stamboliyski abided by the terms he helped set in the peace treaty signed at Neuilly-sur-Seine in November 1919, which was eventually exploited by the nationalist factions of Bulgaria as he failed to lessen the outstanding reparations payments until 1923. Stamboliyski rejected territorial expansion and aimed at forming a Balkan federation of agrarian states, a policy which began with a détente with Yugoslavia. His administration was successful in bringing out land redistribution legislation, creating maximum property holding regulations. It also increased the vocational element in education, especially in rural areas. Being ardently anti-war himself he kept the army below the low level set by the Neuilly treaty, further angering the military by restriction their social status and opportunities for advancement. However, importantly Stamboliyski never settled the Macedonian problem.

On February 2, 1923, Stamboliyski and three of his ministers survived an assassination attempt in the National Theater carried out by the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO).[7] On 4 June 1923 - just few days before the coup, the internal minister Hristo Stoyanov said that if someone kills Stamboliyski or some other leader of BANU "the Pirin region and maybe Kystendil and the capital will look like graveyards."[8] (Pirin Macedonia and the Kyustendil region were the center of power of IMRO in postwar Bulgaria till the 1934 coup and the banning of IMRO that followed the same year).

In 1921 a conspirative Committee for Peasant Dictatorship (Комитет за селска диктатура, Komitet za selska diktatura) was established. The committee became the Union's de facto leadership. In 1922 by the will of the committee the militarized Orange Guard was established to guard the regime. In early 1923 BANU openly discussed the possibility of establishing an agrarianist dictatorship.[9]

The BANU government also made an orthographical reform, simplifying the Bulgarian orthography - the so-called agrarianist or Omarchevski orthography (Омарчевски правопис, Omarchevski pravopis), named after the minister of education Stoyan Omarchevski. The agrarianist orthography was boycotted by the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences and many intellectuals, as well as by the opposition. Immediately after the 9 June coup, the old orthography was restored.

Coup and assassination

[edit]

On March 23, 1923, he signed the Treaty of Niš with the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and undertook the obligation to suppress the operations of the IMRO carried out from Bulgarian territory.[10] On 9 June 1923, Stamboliyski's government was overthrown by a coup composed of the right-wing factions of the Military League, IMRO, the National Alliance, and the army led by Aleksandar Tsankov. Italian agents sent by Mussolini in retaliation against Stamboliyski's refusal to ally with him against Yugoslavia also aided in the coup.[11] With the Communist faction refusing to intervene and the international community uninterested, Stamboliyski was isolated.

As important as the overthrow of Stambolyiski was for Bulgaria, the refusal of the Communist Party of Bulgaria to unite with the Stamboliyski's Agrarians had important ideological consequences for the young Soviet Russia next door. The passivity of the Bulgarian Communists during the June 9 coup in 1923 was bitterly disappointing to nearly all factions within the Russian government and the Bolshevik Party.[12] Stalin, who, by 1923, was gathering power in the absence of Lenin in the leadership of the new Soviet Russian government, had sought close relations with the Stamboliyski government.[13] The Soviet government sought a means to break the ring of isolation that the western powers had erected around the new Soviet nation. Accordingly, following the Russian example, Russian Communists were strongly of the opinion that the Communists in Bulgaria should aid and support what they viewed as "the liberal petty bourgeoisie" —in the form of Stamboliyski's Agrarian Party as a means to advance the interests of the workers in Bulgaria.[14] Indeed, this was the thinking of the Fourth Congress of the Communist International which was held in Moscow in November, 1922.[15] At the Fourth Congress, delegates instructed the Bulgarians to support the Stamboliyski government. Yet in the 1923 coup of Alexander Tsankov in June, 1923, the Bulgarian Communist Party refused to come to the aid of Stamboliyski and following the coup the Communist Party was forced "underground" by the Tsankovist Terror that followed the coup.[16] The Communist International then "ordered" the Bulgarian Communist Party to redress this error of passivity in the face of the successful coup. Accordingly, the Bulgarian Communist Party denied that they had suffered a defeat in the June coup and rose in a hastily arranged uprising in September 1923. This uprising however was quickly defeated by the Tsankov government.[17]

After the coup d'etat, Stamboliyski relocated to his native village of Slavovitsa. From his native village, Stamboliyski was organizing a counter-insurgence that was large in number but weak in arms. On 14 June 1923, he was taken prisoner by activists of the IMRO, brutally tortured, and murdered. The IMRO members were extremely brutal because of his signature on the Treaty of Niš.[18] His hand that signed the Treaty of Niš was cut off.[19] He was also blinded in his torture and his head was cut off and sent to Sofia in a box of biscuits. Besides Stamboliyski, other notable BANU representatives were killed immediately after the coup as well, such as the mayor of Sofia Krum Popov.

Legacy

[edit]

In 1979 the then-Communist government of Bulgaria renamed the town previously known as Novi Krichim to Stamboliyski, in honour of Aleksandar Stamboliyski. A village in Haskovo province has been named after him, as well as one in Dobrich province. A reservoir in Veliko Tarnovo province has also been named after him. Aleksandar Stamboliyski boulevard is a boulevard in central Sofia.

Further reading

[edit]- Bell, John D. Peasants in Power: Alexander Stamboliski and the Bulgarian Agrarian National Union, 1899–1923 (1977).

- Bell, John D.. "The Agrarian Movement in Recent Bulgarian Historiography." Balkanistica 8(1992): 20–35.

- Chary, Frederick B.. The History of Bulgaria. Santa Barbara, Calif.: Greenwood, 2011.

- Crampton, R. J.. Aleksandŭr Stamboliĭski, Bulgaria. London: Haus Publishing, 2009.

- Christov, Christo, and Sofia Jusautor. Alexander Stamboliiski, his life, ideas, and work. Sofia:Bap Printing House, Sofia Press Agency, 1981.

- Gross, Feliks, and George M.Dimitrov. "Agrarianism." In European ideologies, a survey of 20th century political ideas, 196–452. New York: Philosophical Library, 1948.

- Groueff, Stéphane. Crown of Thorns: The Reign of King Boris III of Bulgaria, 1918–1943. Lanham,MD: Madison Books, 1987.

- Mitrany, David. Marx Against the Peasant; A Study in Social Dogmatism.. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1951.

- Oren, Nissan. Revolution Administered: Agrarianism and Communism in Bulgaria. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

- Stamboliski, Alexander. The Principles of the BAP. Sofia: The Bulgarian Agrarian Party, 1919.

- Stamboliski, Alexander. Political Parties or Professional Organizations. 1909. Reprint, Sofia: BANU Printing House, 1945.

- Stavrianos, L.S.. "The Balkan Federation Movement: A Neglected Aspect." The American Historical Review 48, no. 1 (1942): 30–51.

- Sugar, Peter F.. "The Views of the U.S. Department of State of Alexandre Stambolijski." Balkan Studies 2 (1990): 70–77.

References

[edit]- ^ Several different versions of this quote exist, but all contain more or less the same meaning but with slightly different wording, presumably from differing translations. M. D. Stragnakovitch, Oeuvre durapprochement et de l'union des Serbes et des Bulgares dans le passé (Paris: éditions et publications contemporaines Pierre Bossuet, 47, rue de la Gaîté, 1930), 26; Cited from Stavrianos, The Balkan federation, 39; also see J. Swire, The Bulgarian Conspiracy (London: R. Hale, 1939), 142.

- ^ R.J. Crampton, The Historical Dictionary of Bulgaria (Oxford, Oxford University Press: 2007), 228.

- ^ R.J. Crampton, Stamboliski (London: Haus Publishing, 2009), 19. Between 1880 and 1910 the population of towns in Bulgaria even declined slightly, John R. Lampe, “Unifying the Yugoslav Economy, 1918–1921: Misery and Early Misunderstandings,” in Dimitrije Djordjevic, ed., The Creation of Yugoslavia 1914–1918 (Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-Clio Press, 1980), 147–52.

- ^ Crown of Thorns: The Reign of King Boris III of Bulgaria, 1918–1943 , Stephane Groueff, Madison Books, 1998, pp.38–41

- ^ Crampton, Stamboliski, 144.

- ^ Crampton, Bulgaria, 283.

- ^ Chalk, Peter, ed. (2012-11-21). Encyclopedia of Terrorism. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313385353.

... the attempted killing of Bulgarian prime minister Aleksandar Stamboliiski on February 2, 1923;

- ^ Тачев, Стоян (12 June 2019). "Управлението на БЗНС или за силата на цепеницата". Българска история. Archived from the original on 2019-07-04. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Тачев, Стоян (12 June 2019). "Управлението на БЗНС или за силата на цепеницата". Българска история. Archived from the original on 2019-07-04. Retrieved 30 January 2022.

- ^ Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). World War One. ABC-CLIO. p. 1721. ISBN 1-85109-879-8.

On 23 March 1923 Stamboliyski signed the convention of Nish with the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (Yugoslavia). With this agreement, Stamboliyski promised to suppress the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO), which was then carrying out operations against Yugoslavia from Bulgarian territory.

- ^ "From the day Stamboliski turned down Baron Aliotti's offer of a secret military alliance against Yugoslavia, the Italians set out to destroy him. They had three major weapons – bribery, terror, and Bulgarian reparations." Kosta Todorov, Balkan firebrand: the autobiography of a rebel, soldier and statesman (Chicago: Ziff-Davis Pub. Co., 1943), 151.

- ^ Leon Trotsky, "Lessons of October" contained in The Challenge of the Left Opposition: 1923–1925 (Pathfinder Press: New York, 1975) pp. 200–201.

- ^ Ruth Fischer, Stalin and German Communism (Transaction Books: New Brunswick, N.J., 1982) p. 307.

- ^ R. J. Crampton, Bulgaria (Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2007) p. 237.

- ^ Ruth Fischer, Stalin, and German Communism, p. 307.

- ^ See note 22 in The Challenge of the Left Opposition: 1923–1925, p. 417.

- ^ R. J. Compton, Bulgaria, p. 237.

- ^ Lampe, John R. (2000) [1996], Yugoslavia as history: twice there was a country (II ed.), Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 156, ISBN 0-521-77357-1,

The prominent VMRO role in assassinating him shortly thereafter, precisely of that signature

- ^ Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). World War One. ABC-CLIO. p. 1721. ISBN 1-85109-879-8.

IMRO members as well as other opponents of Stamboliyski's foreign and domestic policies murdered him... cutting off the hand that signed the Niš Treaty.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Variously transliterated, such as Aleksandar/Alexander Stamboliyski/Stamboliiski/Stamboliski

External links

[edit]- 1879 births

- 1923 deaths

- People from Pazardzhik Province

- Bulgarian Agrarian National Union politicians

- Prime ministers of Bulgaria

- Ministers of foreign affairs of Bulgaria

- Members of the National Assembly (Bulgaria)

- Agrarianists

- Bulgarian prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment

- Prisoners sentenced to life imprisonment by Bulgaria

- People murdered in Bulgaria

- Assassinated Bulgarian politicians

- Assassinated prime ministers

- 20th-century Bulgarian politicians

- 1923 murders in Bulgaria

- Defence ministers of Bulgaria

- Politicians assassinated in the 1920s

- Torture victims