Anniston, Alabama

Anniston | |

|---|---|

Downtown Anniston in 2012 | |

| Nickname: The Model City | |

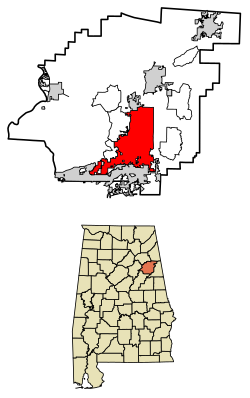

Location of Anniston in Calhoun County, Alabama. | |

| Coordinates: 33°39′40″N 85°50′00″W / 33.66111°N 85.83333°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alabama |

| County | Calhoun |

| Settled | April 1872 |

| Incorporated | July 3, 1883 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Jack Draper (R) |

| Area | |

• City | 45.90 sq mi (118.87 km2) |

| • Land | 45.83 sq mi (118.69 km2) |

| • Water | 0.07 sq mi (0.18 km2) |

| Elevation | 719 ft (219 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 21,564 |

| • Density | 470.57/sq mi (181.69/km2) |

| • Metro | 116,736 (US: 327th) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 36201-36207 |

| Area code | 256 |

| FIPS code | 01-01852 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0159066 |

| Website | www |

Anniston is a city and the county seat of Calhoun County in Alabama, United States, and is one of two urban centers/principal cities of and included in the Anniston–Oxford Metropolitan Statistical Area. As of the 2010 census, the population of the city was 23,106.[2] According to 2019 Census estimates, the city had a population of 21,287.[3] Named "The Model City" by Atlanta newspaperman Henry W. Grady for its careful planning in the late 19th century, the city is situated on the slope of Blue Mountain.

History

[edit]Civil War

[edit]Though the surrounding area was settled much earlier, the mineral resources in the area of Anniston were not exploited until the Civil War. The Confederate States of America operated an iron furnace near present-day downtown Anniston,[4] until it was destroyed by raiding Union cavalry in early 1865. Later, cast iron for sewer systems became the focus of Anniston's industrial output. Cast iron pipe, also called soil pipe, was popular until the advent of plastic pipe in the 1960s.[5]

Woodstock Iron Company

[edit]

In 1872, the Woodstock Iron Company, organized by Samuel Noble and Union Gen. Daniel Tyler, rebuilt the furnace on a much larger scale,[6] and started a planned community named Woodstock, soon renamed "Annie's Town" for Annie Scott Tyler, Daniel's daughter-in-law and wife of railroad president Alfred L. Tyler. Anniston was chartered as a town in 1873.[7]

Though the roots of the town's economy were in iron, steel, and clay pipe, planners touted it as a health resort, and several hotels began operating. Schools also appeared, including the Noble Institute, a school for girls established in 1886,[8] and the Alabama Presbyterian College for Men, founded in 1905.[6] Careful planning and easy access to rail transportation helped grow Anniston. In 1882, Anniston was the first city in Alabama to be lit by electricity.[9] By 1941, Anniston was Alabama's fifth largest city.[10]

World War I and II

[edit]In 1917, at the start of World War I, the United States Army established a training camp at Fort McClellan. On the other side of town, the Anniston Army Depot opened during World War II as a major weapons storage and maintenance site, a role it continues to serve as munitions-incineration progresses. Most of the site of Fort McClellan was incorporated into Anniston in the late 1990s, and the Army closed the fort in 1999 following the Base Realignment and Closure round of 1995.

Civil Rights era

[edit]

Anniston was the center of national controversy in 1961 when a mob bombed a bus filled with civilian Freedom Riders during the American Civil Rights Movement. As two Freedom buses were setting out to travel the south in protest of their civil rights following the Supreme Court case saying bus segregation was unconstitutional, one headed to Anniston, and one to Birmingham, Alabama, before finishing in New Orleans. The Freedom Riders were riding an integrated bus to protest Alabama's Jim Crow segregation laws that denied African Americans their civil rights. One of the buses was attacked and firebombed by a mob outside Anniston on Mother's Day, Sunday, May 14, 1961. Prior to the bus being firebombed, attackers broke windows, and slashed tires, using metal pipes, clubs, chains and crowbars, before the police came to escort the bus away.[11] The bus was forced to a stop just outside of Anniston, in front of Forsyth and Sons grocery, by more mob members.[12] As more windows were broken, rocks and eventually a firebomb were thrown into the bus. As the bus burned, the mob held the doors shut, intent on burning the riders to death. An exploding fuel tank caused the mob to retreat, allowing the riders to escape the bus. The riders were viciously beaten as they tried to flee, where warning shots fired into the air by highway patrolmen prevented the riders from being lynched on the spot.[11] A 12-year-old girl, Janie Forsyth, set out against the mob with a bucket of water and cups to help the Riders, first tending to the one who had looked like her own nanny.[13] Forsyth and Son grocery is located along Alabama Highway 202 about 5 miles (8 km) west of downtown. The site today is home to a historic marker and was designated Freedom Riders National Monument by President Barack Obama in January 2017.[14][15]

In response to the violence, the city formed a bi-racial Human Relations Council (HRC) made up of prominent white business and religious leaders, but when they attempted to integrate the "whites-only" public library on Sunday afternoon, September 15, 1963 (the same day as the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham), further violence ensued and two black ministers, N.Q. Reynolds and Bob McClain, were severely beaten by a mob. The HRC chairman, white Presbyterian minister Rev. Phil Noble, worked with an elder of his church, Anniston City Commissioner Miller Sproull, to avoid KKK mob domination of the city. In a telephone conference with President John F. Kennedy, the President informed the HRC that after the Birmingham church bombing he had stationed additional federal troops at Fort McClellan. On September 16, 1963, with city police present, Noble and Sproull escorted black ministers into the library.[16] In February 1964, Anniston Hardware, owned by the Sproull family, was bombed, presumably in retaliation for Commissioner Sproull's integration efforts.

On the night of July 15, 1965, a white racist rally was held in Anniston, after which Willie Brewster, a black foundry worker, was shot and killed while driving home from work. A $20,000 reward was raised by Anniston civic leaders, and resulted in the apprehension, trial and conviction of the accused killer, Damon Strange, who worked for a leader of the Ku Klux Klan.[17] Historian Taylor Branch called the conviction of Damon Strange a "breakthrough verdict" on p. 391 of his Pulitzer Prize-winning book, At Canaan's Edge. Strange was convicted by an all-white Calhoun County jury to the surprise of many people, including civil rights leaders who had planned to protest an acquittal. This was the first conviction of a white person for killing a black person in civil rights era Alabama.[18]

PCB contamination

[edit]PCBs were produced in Anniston from 1929 to 1935 by the Swann Chemical Company. In 1935 Monsanto Industrial Chemicals Co. bought the plant and took over production, which continued until 1971. In 1969, the plant was discharging about 250 pounds (110 kg) of the chemicals into Snow Creek per day, according to internal company documents.[19]

In 2002, an investigation by 60 Minutes[20] revealed Anniston had been among the most toxic cities in the country. The primary source of local contamination was a Monsanto chemical factory, which had already been closed. The EPA description[21] of the site reads in part:

The Anniston PCB site consists of residential, commercial, and public properties located in and around Anniston, Calhoun County, Alabama, that contain or may contain hazardous substances, including polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) impacted media. The Site is not listed on the NPL, but is considered to be a NPL-caliber site.

Geography

[edit]At the southernmost length of the Blue Ridge, part of the Appalachian Mountains, Anniston's environment is home to diverse species of birds, reptiles and mammals. Part of the former Fort McClellan is now operating as Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge to protect endangered Southern Longleaf Pine species.[citation needed]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 45.7 square miles (118.4 km2), of which 45.6 square miles (118.2 km2) is land and 0.08 square miles (0.2 km2), or 0.15%, is water.[2]

In 2003, part of the town of Blue Mountain was annexed into the city of Anniston, while the remaining portion of the town reverted to unincorporated Calhoun County.[22]

Part of the city limits extend down to Interstate 20, with access from exit 188. Via I-20, Birmingham is 65 mi (105 km) west, and Atlanta is 91 mi (146 km) east.

Climate

[edit]The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Anniston has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[23]

| Climate data for Anniston, Alabama (Anniston Regional Airport) 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1903–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 80 (27) |

84 (29) |

89 (32) |

93 (34) |

98 (37) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

106 (41) |

101 (38) |

100 (38) |

88 (31) |

80 (27) |

106 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 72.4 (22.4) |

75.6 (24.2) |

81.9 (27.7) |

85.6 (29.8) |

90.5 (32.5) |

94.7 (34.8) |

96.7 (35.9) |

96.5 (35.8) |

93.8 (34.3) |

86.9 (30.5) |

79.1 (26.2) |

72.8 (22.7) |

98.2 (36.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 54.7 (12.6) |

59.2 (15.1) |

66.9 (19.4) |

74.7 (23.7) |

81.5 (27.5) |

87.6 (30.9) |

90.2 (32.3) |

89.8 (32.1) |

85.2 (29.6) |

75.6 (24.2) |

65.1 (18.4) |

57.0 (13.9) |

74.0 (23.3) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 44.4 (6.9) |

48.2 (9.0) |

55.4 (13.0) |

62.6 (17.0) |

70.5 (21.4) |

77.4 (25.2) |

80.4 (26.9) |

79.9 (26.6) |

74.6 (23.7) |

63.9 (17.7) |

53.2 (11.8) |

46.8 (8.2) |

63.1 (17.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 34.0 (1.1) |

37.3 (2.9) |

43.8 (6.6) |

50.5 (10.3) |

59.5 (15.3) |

67.2 (19.6) |

70.6 (21.4) |

70.0 (21.1) |

64.0 (17.8) |

52.2 (11.2) |

41.3 (5.2) |

36.6 (2.6) |

52.2 (11.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 16.2 (−8.8) |

21.1 (−6.1) |

26.3 (−3.2) |

34.3 (1.3) |

44.4 (6.9) |

57.0 (13.9) |

63.5 (17.5) |

61.1 (16.2) |

49.4 (9.7) |

35.1 (1.7) |

25.1 (−3.8) |

20.7 (−6.3) |

14.1 (−9.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −5 (−21) |

−4 (−20) |

12 (−11) |

26 (−3) |

34 (1) |

42 (6) |

50 (10) |

50 (10) |

34 (1) |

22 (−6) |

5 (−15) |

1 (−17) |

−5 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 4.84 (123) |

5.08 (129) |

5.37 (136) |

4.43 (113) |

4.35 (110) |

4.37 (111) |

4.68 (119) |

3.51 (89) |

3.11 (79) |

3.25 (83) |

4.53 (115) |

4.60 (117) |

52.12 (1,324) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.9 | 10.7 | 11.1 | 9.3 | 9.6 | 11.5 | 12.2 | 9.6 | 7.1 | 7.6 | 8.5 | 10.7 | 118.8 |

| Source: NOAA[24][25] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 942 | — | |

| 1890 | 9,998 | 961.4% | |

| 1900 | 9,695 | −3.0% | |

| 1910 | 12,794 | 32.0% | |

| 1920 | 17,734 | 38.6% | |

| 1930 | 22,345 | 26.0% | |

| 1940 | 25,523 | 14.2% | |

| 1950 | 31,066 | 21.7% | |

| 1960 | 33,320 | 7.3% | |

| 1970 | 31,533 | −5.4% | |

| 1980 | 29,135 | −7.6% | |

| 1990 | 26,623 | −8.6% | |

| 2000 | 24,276 | −8.8% | |

| 2010 | 23,106 | −4.8% | |

| 2020 | 21,564 | −6.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[26] 2018 Estimate[27] | |||

Anniston first appeared on the 1880 U.S. Census[28] as an incorporated town.

2020 census data

[edit]| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 9,012 | 41.79% |

| Black or African American (non-Hispanic) | 10,565 | 48.99% |

| Native American | 52 | 0.24% |

| Asian | 245 | 1.14% |

| Pacific Islander | 10 | 0.05% |

| Other/Mixed | 768 | 3.56% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 912 | 4.23% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 21,564 people, 9,277 households, and 5,455 families residing in the city.

2010 census data

[edit]As of the census of 2010, there were 23,106 people living in the city. The population density was 506.3 inhabitants per square mile (195.5/km2). There were 11,599 housing units at an average density of 281.5 per square mile (108.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 51.5% Black or African American, 43.6% Non-Hispanic White, 0.3% Native American, 0.8% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, and 1.7% from two or more races. 2.7% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 9,603 households, out of which 20.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 40.0% were married couples living together, 21.0% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.6% were non-families. 34.8% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.26 and the average family size was 2.91.

In the city, the age distribution of the population shows 21.7% under the age of 18, 8.7% from 18 to 24, 25.7% from 25 to 44, 23.3% from 45 to 64, and 17.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39 years. For every 100 females, there were 83.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 78.5 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $30,400, and the median income for a family was $37,067. Males had a median income of $31,429 versus $21,614 for females. The per capita income for the city was $19,689. About 25.1% of families and 29.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 35.2% of those under age 18 and 16.2% of those age 65 or over.

Anniston Precinct/Division (1880–)

[edit]| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1880 | 1,401 | — | |

| 1890 | 10,918 | 679.3% | |

| 1900 | 11,008 | 0.8% | |

| 1910 | 14,602 | 32.6% | |

| 1920 | 18,185 | 24.5% | |

| 1930 | 22,807 | 25.4% | |

| 1940 | 28,836 | 26.4% | |

| 1950 | 37,457 | 29.9% | |

| 1960 | 33,689 | −10.1% | |

| 1970 | 31,637 | −6.1% | |

| 1980 | 83,265 | 163.2% | |

| 1990 | 75,674 | −9.1% | |

| 2000 | 69,376 | −8.3% | |

| 2010 | 68,662 | −1.0% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[30] | |||

Anniston Beat (Precinct) (Calhoun County 15th Beat) first appeared on the 1880 U.S. Census. In 1890, "beat" was changed to "precinct." In 1960, the precinct was changed to "census division" as part of a general reorganization of counties.[31] In 1980, three additional census divisions were consolidated into Anniston, including Oxford, Weaver and West End.[32]

Crime

[edit]Homicides

[edit]| Year | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homicides (city, number)[33] | 7 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 14 | 9 | 13 | 5 | 3 | 11 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 7 |

| Homicides (city, rate)[33] | 28.6 | 8.4 | 25.1 | 20.9 | 58.4 | 37.9 | 55.0 | 21.2 | 12.7 | 47.4 | 21.7 | 22.1 | 17.7 | 35.9 | 31.5 |

| Homicides (US, rate)[33] | 5.6 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.4 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 5.1 |

Arts and culture

[edit]

In 1899, the county seat of Calhoun County moved from Jacksonville to Anniston. More than 100 years later, the community is a bustling center of industry and commerce with more than 22,000 residents. Over the years, city officials and local citizens have worked to retain the environmental beauty of the area while allowing it to thrive economically and to preserve its history. The Spirit of Anniston Main Street Program, Inc., a nonprofit organization started in 1993, spearheaded the restoration and revitalization of historic downtown Anniston, with a focus on the city's main thoroughfare, Noble Street.

The Noble Streetscape Project encouraged local business owners to refurbish storefront façades, while historic homes throughout the downtown area have been repaired and returned to their former condition. The preservation effort included the historic Calhoun County Courthouse, located on the corner of 11th Street and Gurnee Avenue since 1900. The original building burned down in 1931, but the courthouse was rebuilt a year later. Thanks to a complete restoration in 1990, the stately structure is still in use today.

Anniston has long been a cultural center for northeastern Alabama. The Alabama Shakespeare Festival was founded in the city in 1972 and remained there until moving to Montgomery in 1985 seeking more robust financial support. The Knox Concert Series produces an annual season of world-renowned musical and dance productions, and the Community Actors' Studio Theatre community theatre organization performs plays, musicals, and revues featuring local performers, actors, and musicians. CAST also features specially funded programs to educate area children in the arts for free. The city is home to the Anniston Museum of Natural History and the Berman Museum of World History. These institutions house mummies, dioramas of wildlife, and artifacts from a bygone age in contemporary, professional displays and exhibits. The Alabama Symphony Orchestra since 2004 has performed a summer series of outdoor concerts, Music at McClellan, at the former Fort McClellan.

The city has many examples of Victorian-style homes, some of which have been restored or preserved. Several of the city's churches are architecturally significant or historic, including the Church of St. Michael and All Angels, Grace Episcopal Church, Parker Memorial Baptist Church, and the Mount Zion Missionary Baptist Church, a predominantly African-American church in what is known as the Zion Hill community. Temple Beth El, dedicated in 1893, is the oldest building in the state continuously used for Jewish worship.

The original main street, Noble Street, is seeing a rebirth as a shopping and dining district in the heart of downtown.

The Chief Ladiga Trail, part of a 90-mile (140 km) paved rail trail with the Silver Comet Trail of Georgia, has its western terminus in Anniston.

Anniston was featured in the fifteenth episode of the Small Town News Podcast, an improv comedy podcast that takes listeners on a fun and silly virtual trip to a small town in America each week, in which the hosts improvise scenes inspired by local newspaper stories.[34]

Fort McClellan

[edit]Fort McClellan—former site of the U.S. Army Military Police Training Academy, a Vietnam era Infantry Training Center, Chemical Corps Regimental Headquarters, Chemical Warfare training center, and Women's Army Corps Headquarters—was decommissioned in the 1990s. A portion of the former fort is now home to the Alabama National Guard Training Center. Another 9,000 acres (36 km2) of the fort were set aside for the Mountain Longleaf National Wildlife Refuge in 2003. The Department of Homeland Security also uses a portion of the decommissioned fort for the Center for Domestic Preparedness, the nation's only civilian "live agent" training center; emergency response providers from all over the world come to Fort McClellan to be trained in dealing with live agents and weapons in a real-time, monitored setting.[citation needed]

Government

[edit]Anniston is governed by Alabama's "weak mayor" form of city government. Four city council members are elected to represent the city's four wards, and the mayor is elected at-large. Day-to-day functions of city government are carried out by the city manager, who is appointed by the mayor and city council.

The current five-member city council are Jack Draper (mayor), Jay Jenkins (Ward 1), D.D. Roberts (Ward 2), Ciara Smith (Ward 3 and vice-mayor), and Millie Harris (Ward 4).[35]

Anniston is the county seat of Calhoun County, Alabama. Circuit and district courts for the county and the district attorney's office are located in the Calhoun County Courthouse at the corner of 11th Street and Gurnee Avenue. Other county administrative offices are in the Calhoun County Administrative Building at the corner of 17th and Noble streets, and a United States Courthouse, part of the U.S. Alabama Northern District Court, is located at the corner of 12th and Noble streets.

Education

[edit]Public schools in Anniston are operated by Anniston City Schools. These include:

- Anniston High School (Grades 9–12)

- Anniston Middle School (Grades 6–8)

- Golden Springs Elementary School (Grades 1–5)

- Randolph Park Elementary School (Grades 1–5)

- Cobb Pre-School Academy (Pre-K)

Statewide testing ranks the schools in Alabama. Those in the bottom six percent are listed as "failing". As of early 2018, Anniston High School was included in this category.[36]

A public four-year institution of higher learning, Jacksonville State University, is located 12 miles (19 km) to the north in Jacksonville. Anniston is home to some satellite campuses of Gadsden State Community College, both at the former Fort McClellan and at the Ayers campus in southern Anniston.

There are several private primary and secondary schools in Anniston, including:

- Faith Christian School

- Sacred Heart of Jesus School, a longstanding Roman Catholic school

- The Donoho School, a K–12 college-preparatory school

An obelisk installed in 1905 commemorates "Dr. Clarence J. Owens, president of the Anniston College for Young Ladies".[37]

| % Black | Note | |

|---|---|---|

| Anniston City Population | 52% | [26] |

| The Donoho School (Private) | 8% | [38] |

| Sacred Heart of Jesus Catholic School (Private) | 14% | [39] |

| Faith Christian School (Private) | 6% | [40] |

| Anniston High School (Public) | 95% | [41] |

| Anniston Middle School (Public) | 88% | [42] |

| Golden Springs Elementary School (Public) | 81% | [43] |

| Randolph Park Elementary School (Public) | 95% | [44] |

| Tenth Street Elementary School (Public) | 84% | [45] |

Former schools in Anniston include the Anniston Normal and Industrial School (1898–c. 1915), a private Baptist school for African American students during the time of segregation.[46]

Media

[edit]Anniston is served by two daily newspapers: The Birmingham News statewide edition, and the local 25,000 circulation daily paper, The Anniston Star. Anniston-based Consolidated Publishing Co., publisher of The Anniston Star, also owns and operates advertising-supported newspapers in nearby Jacksonville, Piedmont and Cleburne County. Local radio stations include WHMA AM and FM and WHOG 1120 AM.

WEAC-CD is the only television station that directly broadcasts from the Anniston area, but many Birmingham stations have towers and news bureaus here, such as WJSU-TV (WJSU is a local broadcast station for Birmingham-based ABC 33/40), WBRC-TV (Fox), and WVTM-TV (NBC). Alabama Public Television erected its tallest tower atop Cheaha Mountain 12 miles (19 km) south of Anniston. WJSU-TV 40 was historically a local CBS affiliate, broadcasting local newscasts daily.

Formerly its own Arbitron-defined broadcast market, today Anniston is a part of the Birmingham-Anniston-Tuscaloosa television designated market area. Radio stations are divided into three sub markets within that market; Anniston is in the Anniston-Gadsden–Talladega radio sub market.

Infrastructure

[edit]Transportation

[edit]The following major highways pass through Anniston:

U.S. Highway 431 (Anniston Eastern Bypass/Golden Springs Road)

U.S. Highway 431 (Anniston Eastern Bypass/Golden Springs Road) State Route 21 (Quintard Avenue/McClellan Boulevard)

State Route 21 (Quintard Avenue/McClellan Boulevard) State Route 202

State Route 202

The Anniston Western Bypass runs from Interstate 20 in Oxford (the Coldwater exit) and runs north into the present State Route 202. It is five lanes wide, handling Anniston Army Depot traffic. Future plans will extend it on the present County Road 109 by widening it to connect with US 431. State Route 202 follows this route from CR 109 (Bynum-Leatherwood Road) southward.

The Anniston Eastern Bypass was a stalled project of the Alabama Department of Transportation to build a four-lane highway in Calhoun County until revived by the 2009 federal stimulus package.[47] It was the largest influx of federal money into the local economy since Fort McClellan closed. More than $21 million was earmarked for this project in 2005. This funding was spent acquiring rights of way and grading a section of the proposed bypass from Oxford to the community of Golden Springs. As of April 2009, the section was a graded, but undriveable, clay dirt road bed. The Eastern Bypass was revived by the 2009 Federal Stimulus Package and was opened to traffic into McClellan on the northwest end in January 2011. As of December 2015, the route is now open to traffic and carries US-431 from the Saks community southward.

Amtrak serves Anniston with its Crescent service, operating to and from New Orleans and New York.[48] Southbound trains depart at 10:30am, and northbound trains depart at 6:59pm (central time).[49]

The Areawide Community Transportation System (ACTS) provides fixed-route bus and paratransit services within Anniston and Oxford. The service operates Monday through Friday from 6:00 AM to 6:00 PM and on Saturdays from 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM. There is no service on Sundays.

Anniston Army Depot

[edit]Anniston is home to the Anniston Army Depot which is used for the maintenance of most Army tracked vehicles. The depot also housed a major chemical weapons storage facility, the Anniston Chemical Activity, and a program to destroy those weapons, the Anniston Chemical Agent Disposal Facility. In 2003, the Anniston Army Depot began the process of destroying the chemical weapons it had stored at the depot and at Fort McClellan. An incinerator was built to destroy the stockpile of Sarin, VX nerve agent, and mustard blister agent stored at the depot. Destruction of the weapons was completed in 2011.[50] The incinerator and related operations were officially closed in May 2013, and the incinerator was disassembled and removed from the depot at the end of 2013.[50]

Health care

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2024) |

Notable people

[edit]- Jonathan Allen, NFL football player

- General Edward "Ned" Almond, active during Korean War

- George T. Anderson, Civil War general

- Ray Anderson, boxer

- Michael Biehn, actor

- Larry Bowie, former NFL player

- Anne Braden, civil rights activist

- Winifred Burks-Houck, organic chemist

- June Burn, author

- Keith Butler, NFL player and football coach

- Red Byron, NASCAR driver

- Asa Earl Carter, segregationist, speech writer, and author of The Education of Little Tree

- Quinton Caver, NFL player

- B. B. Comer, 33rd Governor of Alabama

- John Craton, classical composer

- Louie Crew, emeritus professor, poet, gay activist

- Michael Curry, NBA player, Florida Atlantic University head coach

- Cow Cow Davenport, boogie-woogie pianist

- Eric Davis, NFL cornerback

- William Levi Dawson (1899–1990), composer, whose best-known work is his Negro Folk Symphony

- Nannie Doss, serial killer

- Bobby Edwards, country music singer known for "You're the Reason"

- Ruth Elder, pilot, first female aviator to attempt to cross the Atlantic in 1927, founding member of the 99's, silent movie actress

- Andra Franklin, NFL football player

- David F. Friedman, filmmaker and film producer

- James R. Hall, retired Lieutenant General, U.S. Army; final commanding officer of the Fourth United States Army

- William C. Hamilton Jr., last commanding officer of the USS Enterprise (CVN-65), the world's first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier.[51]

- James Harman, blues singer, harmonica player

- Audrey Marie Hilley, infamous for poisoning her husband and trying to poison her daughter

- Delvin Lamar Hughley, NFL and Arena Football player

- Ken Hutcherson, NFL player and religious leader

- Thomas Kilby, eighth Lieutenant Governor of Alabama and the 36th Governor of Alabama[52]

- Douglas Leigh, innovative lighting designer of Times Square and Empire State Building

- Perry Lentz, author and professor of English

- Harry Mabry, television news director and anchor

- Kivuusama Mays, former NFL player

- Lucky Millinder, rhythm and blues and swing bandleader and singer

- George C. Nichopoulos, physician known as Dr. Nick; raised in Anniston

- Robert Ernest Noble, U.S. Army major general[53]

- Tommy O'Brien, MLB third base and outfielder; born, died and interred in Anniston

- Katherine Orrison, author and film historian

- Will Owsley, Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter

- John L. Pennington, newspaper publisher, governor of Dakota Territory

- Tito Perdue, novelist, was raised in Anniston.[54]

- Troymaine Pope, NFL player

- John Reaves, quarterback, University of Florida and NFL

- Mike D. Rogers, congressman from Alabama's 3rd district

- David Satcher, Surgeon General, 1998–2002

- Patrick "J. Que" Smith, Grammy-winning songwriter

- Tremon Smith, cornerback for the Kansas City Chiefs

- Willie Smith, MLB pitcher and outfielder

- Shannon Spruill, professional wrestler

- Vaughn Stewart, former NFL player

- Vaughn Stewart III, delegate in Maryland General Assembly

- Max Wellborn, chairman and governor of Atlanta Fed

See also

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 29, 2021.

- ^ a b "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Anniston city, Alabama". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved May 30, 2014.

- ^ "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- ^ "The Spirit of Anniston - Historic Photos". Archived from the original on May 10, 2010.

- ^ Levlin, Erik (December 15, 2004). "Water and Waste Pipes" (PDF). p. 2.

- ^ a b Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 2 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 74.

- ^ Sprayberry, Gary. "Anniston". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- ^ located along Leighton Ave, on the corner of Leighton Ave and E 11th St., facing Christine Ave.

- ^ "About Anniston". Annistonal.gov. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ Writer's Program. The WPA Guide to Alabama. New York: Hastings House, 1941. p. 159. Republished in 2013 by Trinity University Press, San Antonio, TX.

- ^ a b Gross, Terry. "Get on the Bus: The Freedom Riders of 1961". NPR. Retrieved May 15, 2017.

- ^ "The Young Witness". PBS. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- ^ Lee, Cynthia. "A single act of kindness becomes part of civil rights lore". newsroom.ucla.edu. Archived from the original on May 9, 2017. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- ^ Whisenhunt, Dan (May 13, 2007). "A Single Step: Memorial to 'Freedom Riders' Just a Beginning". Jacksonville State University News. Jacksonville State University. Retrieved January 8, 2010.

- ^ "Freedom Riders National Monument". National Park Service.

- ^ Beyond the Burning Bus: The Civil Rights Revolution in a Southern Town by Phil Noble, p. 123

- ^ "The Death of Willie Brewster: Memories of a Dark Time". Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved September 13, 2010.

- ^ ""The Death of Willie Brewster: An appraisal of Anniston's moment of shame and triumph."". Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Poisoned By PCBs: "A Lack of Control"". Chemical Industry Archives. Environmental Working Group. Archived from the original on December 10, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ "Toxic Secret". 60 Minutes. August 31, 2003. CBS.

- ^ "U.S.EPA Fact Sheet Anniston PCB Site" (PDF). United States Environmental ProtectionAgency. August 2002. Retrieved April 22, 2010.

- ^ "U.S.Census change list". Census.gov. Archived from the original on February 6, 2006. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Anniston, Alabama Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.com. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Anniston Metro AP, AL". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ a b "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ "Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 8, 2018.

- ^ "Table III - Population of Civil Divisions less than counties, in the aggregate at the Censuses of 1880 and 1870" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1880.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "Number of Inhabitants - Alabama" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. 1960.

- ^ Bureau of the Census (April 1982). "1980 Census Characteristics of the Population - Number of Inhabitants - Alabama" (PDF).

- ^ a b c "Crime Rate in Anniston, Alabama". City Data. Retrieved February 15, 2018.

- ^ "Small Town News".

- ^ "City Council". Annistonal.gov. Retrieved November 18, 2024.

- ^ Crain, Trisha (January 25, 2018). "Failing Alabama public schools: 75 on newest list, most are high schools". AL.com. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ saopaulo1 (2008). "Major John Pelham - Anniston, AL - Obelisks on Waymarking.com". waymarkings.com. Retrieved April 15, 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Donoho School". School Digger. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "Sacred Heart of Jesus Catholic School - Anniston". Niche. Archived from the original on January 27, 2018. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "Faith Christian School". Niche. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "Anniston High School". School Digger. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "Anniston Middle School". School Digger. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "Golden Springs Elementary School". School Digger. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "Randolph Pk Elementary School". School Digger. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ "Tenth Street Elementary School". School Digger. Retrieved January 27, 2018.

- ^ O'Dell, Kimberly (2000). Anniston. Arcadia Publishing. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-7385-0601-2 – via Google Books.

- ^ Goodman, Sherri C. (February 13, 2009). "Anniston bypass, Huntsville overpass are big winners if Obama OKs stimulus plan". The Birmingham News. Retrieved April 16, 2014.

- ^ "Crescent Train New York, Atlanta, New Orleans". Amtrak.

Select map, then Alabama

- ^ "Crescent". North Carolina Department of Transportation.

- ^ a b Gore, Leada (May 8, 2013). "One year after last chemical weapon destroyed, incinerator at Anniston Army Depot closed". AL.com. Alabama Media Group. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ Baird, Dave (November 23, 2011). "Auburn Graduate's Ship Celebrates Anniversary". WBMA.

- ^ "Thomas Erby Kilby". Alabama Department of Archives & History. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ^ Hall, Cody (September 19, 1956). "Gen. Noble Passes at 85 In Hospital". The Anniston Star. Anniston, AL. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Jim Knipfel, "America's Lost Literary Genius," New York Press (12 June 2001). http://www.nypress.com/tito-perdue-americas-lost-literary-genius/

Further reading

[edit]- Grace Hooten Gates, The Model City of the New South: Anniston, Alabama, 1872–1900. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1996.

- Kimberly O'Dell, Anniston. Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2000.

- Ellen Griffith Spears, Baptized in PCBs: Race, Pollution, and Justice in an All-American Town. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2013.

External links

[edit]- City of Anniston official website

- Institute of Southern Jewish Life's History of Anniston

- "Anniston" Archived July 18, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Encyclopedia of Alabama