Quetzalcoatlus: Difference between revisions

Tangent747 (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 216.100.95.80 to last revision by Dinoguy2 (HG) |

|||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

[[Category:Cretaceous pterosaurs]] |

[[Category:Cretaceous pterosaurs]] |

||

[[Category:Prehistoric reptiles of North America]] |

[[Category:Prehistoric reptiles of North America]] |

||

coolio yeah |

|||

[[ca:Quetzalcoatlus]] |

[[ca:Quetzalcoatlus]] |

||

[[cs:Quetzalcoatlus]] |

[[cs:Quetzalcoatlus]] |

||

Revision as of 19:21, 30 March 2009

| Quetzalcoatlus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed Quetzalcoatlus skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Quetzalcoatlus Lawson, 1975

|

| Species | |

|

Q. northropi Lawson, 1975 (type) | |

Quetzalcoatlus (named for the Aztec feathered serpent god Quetzalcoatl) was a pterodactyloid pterosaur known from the Late Cretaceous of North America (Campanian–Maastrichtian stages, 75–65 ma), and one of the largest known flying animals of all time. It was a member of the Azhdarchidae, a family of advanced toothless pterosaurs with unusually long, stiffened necks.

Discovery and species

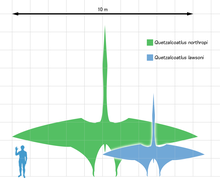

The first Quetzalcoatlus fossils were discovered in Texas (from the Javelina Formation at Big Bend National Park) in 1971 by Douglas A. Lawson. The specimen (numbered TMM 41450-41453) consisted of a partial wing (made up of the forearms and elongated 4th finger in pterosaurs), from an individual later estimated at over to 10 m (33 ft) in wingspan.[1] Lawson assigned the specimen to a new genus and species, Quetzalcoatlus northropi. [2] A second, yet-unnamed species from Texas was reported by Kellner and Langston in 1996.[3] The specimen (known provisionally as Q. sp.) is more complete than Q. northropi, and includes a partial skull, though it is much smaller, with an estimated wingspan of 5.5 meters (18 ft).[4]

An azhdarchid neck vertebrae, discovered in 2002 from the Hell Creek Formation, may also belong to Quetzalcoatlus. The specimen (BMR P2002.2) was recovered accidentally when it was included in a field jacket prepared to transport part of a tyrannosaur specimen. Despite this association with the remains of a large carnivorous dinosaur, it shows no evidence that it was fed on by the dinosaur. The bone came from an individual pterosaur estimated to have had a wingspan of 5 - 5.5m (16.5 - 18 ft).[5]

In 1995, a partial skeleton of a juvenile azhdarchid was discovered in Dinosaur Provincial Park, probably from Quetzalcoatlus or another closely related animal. The carcass had been scavenged by the small dromaeosaurid Saurornitholestes, which broke off a tooth on one of the wing bones. This damaged tooth indicates that the bones of Quetzalcoatlus and other azhdarchids were probably very robust, despite their extreme thinness. [6]

Paleobiology

There are a number of different ideas about the lifestyle of Quetzalcoatlus. With its long neck vertebrae and long toothless jaws it might have fed on fish like a heron, or perhaps it scavenged like the Marabou Stork. Others maintain that it fed like modern-day skimmers. Presumably Quetzalcoatlus could take off under its own power, but once aloft it may have spent much of its time soaring. On the ground, Quetzalcoatlus probably walked on all fours. Recent studies suggest that it may have hunted on the ground like a modern stork, using flight as a method of long-range transport.[1]

The largest remains indicate an individual with a wingspan as large as 12 m (40 ft), though more recent estimates based on greater knowledge of azhdarchid proportions place its wingspan at 10-11 meters (33-36 ft). However, similar claims to an upper size limit for flight accompanied the discovery of large (up to 9 m (30 ft)) Pteranodon, and azhdarchids larger than Quetzalcoatlus with wingspans 12 meters or more (such as Hatzegopteryx) have been discovered.[4]

Mass estimates for giant azhdarchids are extremely problematic because no existing species share a similar size or body plan, and as a result published results vary widely.[1] A 2002 study suggested a body mass of 90–120 kilograms (200–260 lb) for Quetzalcoatlus, considerably lower than most other recent estimates.[7] Higher estimates tend toward 200–250 kilograms (440–550 lb).[8]

During the Cretaceous period, Texas' climate was similar to modern tropical coastal wetlands and lagoons, extending along the Cretaceous Seaway that filled the center of North America. Bones of related animals are also known from Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada.

Along with the dinosaurs, Quetzalcoatlus became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous period.

In popular culture

Quetzalcoatlus is featured in the nature documentary Walking with Dinosaurs episode "Death of a Dynasty", 3rd episode of Dinosaur Planet, When Dinosaurs Roamed America, episode 5 (Late Cretaceous), and episodes of Animal Armageddon. There is a fictional species of Quetzalcoatlus known as Skybax in the Dinotopia series.

References

- ^ a b c Witton, M.P., and Naish, D. (2008). "A Reappraisal of Azhdarchid Pterosaur Functional Morphology and Paleoecology." PLoS ONE, 3(5): e2271. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002271Full text online

- ^ Lawson, D. A. (1975). "Pterosaur from the Latest Cretaceous of West Texas. Discovery of the Largest Flying Creature." Science, 187: 947-948.

- ^ Kellner, A.W.A., and Langston, W. (1996). "Cranial remains of Quetzalcoatlus (Pterosauria, Azhdarchidae) from Late Cretaceous sediments of Big Bend National Park, Texas." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 16: 222–231.

- ^ a b Buffetaut, E., Grigorescu, D., and Csiki, Z. (2002). "A new giant pterosaur with a robust skull from the latest Cretaceous of Romania." Naturwissenschaften, 89: 180–184.

- ^ Henderson, M.D. and Peterson, J.E. "An azhdarchid pterosaur cervical vertebra from the Hell Creek Formation (Maastrichtian) of southeastern Montana." Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 26(1): 192–195.

- ^ Currie, Philip J.; Jacobsen, Aase Roland (1995). "An azhdarchid pterosaur eaten by a velociraptorine theropod" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 32: 922–925.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Atanassov1, Momchil N.; Strauss, Richard E. (2002). "How much did Archaeopteryx and Quetzalcoatlus weigh? Mass estimation by multivariate analysis of bone dimensions". Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Paul, Gregory S. (2002). Dinosaurs of the Air: The Evolution and Loss of Flight in Dinsaours and Birds. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 472. ISBN 0801867630.

External links

coolio yeah