Pyroraptor

| Pyroraptor Temporal range: Late Cretaceous

~ | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

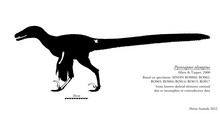

| Figured material of Pyroraptor restored as a generalized dromaeosaurid and an unenlagiine | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Dromaeosauridae |

| Genus: | †Pyroraptor Allain & Taquet, 2000 |

| Species: | †P. olympius

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Pyroraptor olympius Allain & Taquet, 2000

| |

Pyroraptor (meaning "fire thief") is an extinct genus of paravian dinosaur, probably a dromaeosaurid or unenlagiid, from the Late Cretaceous Ibero-Armorican island, of what is now southern France. It lived during the late Campanian and early Maastrichtian stages, approximately 72 million years ago. It is known from a single partial specimen that was found in Provence in 1992, after a forest fire. The animal was named Pyroraptor olympius by Allain and Taquet in 2000.

Discovery and naming

[edit]Naming and Material

[edit]The first remains of Pyroraptor olympius, or P. olympius, were discovered in southeastern France, at the La Boucharde locality of the Arc Basin in Provence. It was described and named by French paleontologists Ronan Allain and Philippe Taquet in 2000, the type species and so far the only species is Pyroraptor olympius. The generic name comes from πῦρ (pûr, Greek for "fire") and raptor (Latin for "thief"), since its remains were discovered after a forest fire that occurred in 1992. The specific name is derived from Mont Olympe, the mountain in Provence at the foot of which the animal's remains were unearthed.[1]

The holotype specimen, MNHN BO001, consists of the second toe claw of the left foot. The assigned paratypes include the equivalent claw of the right foot; the left second metatarsal; another, more complete second toe claw; a right ulna (long forearm bone); and two teeth. Additional material was referred to Pyroraptor, including five pedal digits, one manual digit, a piece of a metacarpal, a right radius, a dorsal vertebra, and a tail vertebra.[1]

Some teeth from the Iberian peninsula of North Eastern Spain have been compared to those referred to Pyroraptor, suggesting that Pyroraptor may have also inhabited Spain; however, a 2022 reevaluation of these teeth states that they cannot be confidently assigned to Pyroraptor and may belong to a whole different variety of European dromaeosaurids.[2][3]

Relation to Variraptor

[edit]

Finds of dromaeosaurid dinosaur remains are rare in Europe and typically provide little taxonomic information. The first dromaeosaurid fossils found in France were those of Variraptor mechinorum, described by Jean Le Lœuff and Eric Buffetaut. Allain and Taquet considered Variraptor mechinorum to be a nomen dubium on the basis that fossil material of the species was collected from localities different from that of the holotype, and that the material did not have enough diagnostic traits to warrant the naming of a new species.[1] However, one of the authors that named Variraptor, Jean Le Lœuff, points out in a conversation that the same reasons given for considering Variraptor mechinorum to be a nomen dubium would apply to Pyroraptor olympius as well, since Pyroraptor's remains present the exact same problems.[4]

In a 2009 description of new dromaeosaurid remains assigned to Variraptor mechinorum, Phornphen Chanthasit and Eric Buffetaut addressed the claims of Allain & Taquet by mentioning that the original description of Variraptor mechinorum very clearly distinguished the holotype from any referred material and argue that some of the material very clearly belongs to the same individual while also elucidating that the situation with Pyroraptor is quite similar. However, due to the disarticulated nature of Pyroraptor remains, it's unknown if they belong to the same individual.[4] This suspicion is affirmed by a 2012 study that states the known Pyroraptor material to belong to at least two different individuals.[5]

The other criticism of Allain and Taquet, that there are not enough diagnostic features to support the validity of Variraptor, is also addressed by the description of new and overlapping Variraptor remains from the same locality as the holotype Variraptor specimen, some of which are stated to undeniably belong to the holotype individual, thus adding new diagnostic traits and establishing the validity of Variraptor mechinorum. The authors also bring light to the fact that Allain and Taquet did not provide enough diagnosable traits to establish the holotype of Pyroraptor as a valid species, noting that most features stated for diagnosis are not unique to Pyroraptor but are simply widespread traits of dromaeosaurs.[4] A 2012 study also agrees that Pyroraptor's "unique" traits are widespread features of dromaeosauridae while also ruling out some of the other "unique traits" as results of preservation deformation.[5]

Since the two existed at the same time and place, the possibility of a synonymy between Pyroraptor and Variraptor is raised but it is concluded that due to the current lack of overlap in material, this possible synonymy cannot yet be tested and more remains are needed.[4]

Description

[edit]

Estimated to measure 1.5 m (4.9 ft), Pyroraptor olympius was a dromaeosaurid, a small, bird-like predatory theropod that possessed enlarged curved claws on the second toe of each foot for predation; these claws were 6.6 cm (2.6 in) long for Pyroraptor.[1] As in other dromaeosaurids, these claws might have been used as weapons[6] or as climbing aids.[7] Its two known teeth are flattened and curved backwards, with their rear margins having finer serrations than at the front.[1]

As a dromaeosaurid, Pyroraptor likely had well-developed forelimbs with curved claws, and probably balanced the body with a long, thin tail. Pyroraptor was also covered in feathers, as many of its relatives, like Microraptor and Sinornithosaurus, also had plumage.[8]

Classification

[edit]Although Pyroraptor olympius has been shown to be a dromaeosaurid, in its initial description it was noted that due to the paucity of remains, not enough diagnostic features can be gathered to create a good comparison with other dromaeosaurids. This concern has been echoed by others, most notably in a 2012 phylogeny of paravians where Pyroraptor was found to wildly fluctuate in its position within Dromaeosauridae.[1][5] Due to its status as a "wildcard taxa", Pyroraptor is known to create issues in phylogenies which are only fixed when it is pruned from the analysis.[5] Hence, this taxon has rarely been used since in phylogenies, which causes difficulty in pinning its precise classification.

Pyroraptor was included in a 2014 phylogeny of Microraptor, as with most trees including Pyroraptor, this caused a polytomy as seen in the cladogram below.[9] This polytomy was also repeated in a phylogeny of Archaeopteryx from the same year.[10]

In the 2019 description of Hesperornithoides, a phylogeny tree found Pyroraptor to be an unenlagiine. The study noted that this is biostratigraphically and geographically consistent with Cretaceous Europe showing a trend of hosting typically Gondwanan species.[11]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This is also consistent with some previous studies, such as a 2005 study where it was suggested that some laurasian dromaeoaurids like Pyroraptor could be considered part of Gondwanan lineages, but scant material from European forms prevented this idea from being tested at the time.[12][13] A 2012 phylogeny study noted that despite being an unstable taxa, Pyroraptor never fell within any of the laurasian dromaeosaur groups.[5] The 2022 description of Vectiraptor greeni noted that the foot morphology of Pyroraptor olympius had more similarities with unenlagiines than with eudromaeosaurs, lending support to the idea that European raptors were closely related to Southern forms from Africa and South America.[14] Another subsequent 2022 study that describes a newly discovered dromaeosaurid sickle claw from the same geologic formation as Pyroraptor, compared the sickle claws with those of Pyroraptor and other dromaeosaurids, and more similarities between Pyroraptor and other unenlagiines were found, this time in the anatomy of the claws.[15]

Two separate studies from 2011 regarding unenlagiines, where the teeth of Pyroraptor were compared to those of South American Unenlagiines found that although not significantly, some similarities in cross section were noticeable.[16][17] But Unenlagiine teeth do not have any serrations on their edges and are usually fluted, a trait that is in direct contradiction with what is seen in Pyroraptor teeth which are serrated, as is typical of dromaeosaurs, the 2021 description of Ypupiara lopai rules out Pyroraptor as being an unenlagiid due to this dissimilarity.[18] However, a 2022 study points out that if Pyroraptor is an unenlagiid, then this would mean that not all unenlagiids would have fluted, unserrated teeth.[3]

During the initial description of Pyroraptor olympius, the suggested model of dromaeosaurid evolution proposed that the dromaeosaurs originated from North America or Euro-America, and then dispersed into Asia. On the basis of newly discovered Early Cretaceous material from China, this dispersal model has since lost support, so Allain and Taquet postulated that perhaps European dromaeosaurids such as Pyroraptor olympius were the remnants of Late Jurassic or Early Cretaceous fauna that evolved separately during the late Cretaceous isolation of Southern Europe.[1]

However, recent studies show that Pyroraptor along with other European raptors, likely originated from the Southern continent of Gondwana. as its anatomy is more consistent with the Gondwanan Unenlagiines than with eudromaeosaurs. This is congruent with other Late Cretaceous European fauna, which are typically Gondwanan lineages.[11][14][5][13][12][3]

Paleoecology

[edit]

Pyroraptor olympius is known from the Argiles et Grès à Reptiles Formation of what is now Southern France. During the Late Cretaceous, it was one part of the island landmass known as Ibero-Armorica, formed from what is today Southern France and Northern Spain in the Tethys Ocean.[19]

At that time, Pyroraptor would have coexisted alongside a variety of species such as Zalmoxes, Rhabdodon priscus, Ampelosaurus atacis, Lirainosaurus astibiae, Atsinganosaurus velauciensis, some undescribed titanosaurids, Arcovenator escotae, Tarascosaurus salluvicus, Struthiosaurus sp., Variraptor mechanorum, Gargantuavis philoinos, Martinaves cruzyensis, and non-dinosaurs such as the pterosaurs Azhdarcho lancicollis and Hatzegopteryx thambema, the crocodylomorphs Musturzabalsuchus buffetauti, Massaliasuchus, and Allodaposuchus, the turtles Dortoka, and Solemydid turtles, zhelestid eutherians, palaeobatrachid anurans, batrachosauroidid urodeles, amphisbaenian and/or anguid squamates, and derived alethinophidian snakes.[1][3][19][2]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Allain, R.; Taquet, P. (2000). "A new genus of Dromaeosauridae (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of France". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 20 (2): 404–407. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0404:ANGODD]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Pereda-Suberbiol, X.; Corral, J.C.; Astibia, H.; Badiola, A.; Bardet, N.; Berreteaga, A.; Buffetaut, E.; Buscalioni, A.D.; Cappetta, H.; Cavin, L.; Díez Díaz, V. (2015-05-08). "Late cretaceous continental and marine vertebrate assemblages from the Laño quarry (Basque-Cantabrian Region, Iberian Peninsula): an update". Journal of Iberian Geology. 41 (1): 101–124. doi:10.5209/rev_JIGE.2015.v41.n1.48658. hdl:10486/679211. ISSN 1886-7995.

- ^ a b c d Isasmendi, Erik; Torices, Angelica; Canudo, José Ignacio; Currie, Philip J.; Pereda‐Suberbiola, Xabier (2022). "Upper Cretaceous European theropod palaeobiodiversity, palaeobiogeography and the intra‐Maastrichtian faunal turnover: new contributions from the Iberian fossil site of Laño". Papers in Palaeontology. 8 (1). doi:10.1002/spp2.1419. hdl:10810/56781. ISSN 2056-2799. S2CID 246028305.

- ^ a b c d Chanthasit, Phornphen; Buffetaut, Eric (2009-03-01). "New data on the Dromaeosauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Late Cretaceous of southern France". Bulletin de la Société Géologique de France. 180 (2): 145–154. doi:10.2113/gssgfbull.180.2.145. ISSN 1777-5817.

- ^ a b c d e f Turner, Alan H.; Makovicky, Peter J.; Norell, Mark A. (2012-08-17). "A Review of Dromaeosaurid Systematics and Paravian Phylogeny". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 371: 1–206. doi:10.1206/748.1. ISSN 0003-0090. S2CID 83572446.

- ^ Carpenter, Kenneth (1998). "Evidence of predatory behavior by theropod dinosaurs" (PDF). Gaia. 15: 135–144.

- ^ Manning, Phil L., Payne, David., Pennicott, John., Barrett, Paul M., Ennos, Roland A. (2005) "Dinosaur killer claws or climbing crampons?" Biology Letters (2006) 2; pg. 110-112 doi:10.1098/rsbl.2005.0395

- ^ Scott Sampson in Discovery Channel's 2003 documentary series Dinosaur Planet, ep. 2: "Pod's Travels".

- ^ Pei, Rui; Li, Quanguo; Meng, Qingjin; Gao, Ke-Qin; Norell, Mark A. (2014-12-22). "A New Specimen of Microraptor (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae) from the Lower Cretaceous of Western Liaoning, China". American Museum Novitates (3821): 1–28. doi:10.1206/3821.1. ISSN 0003-0082. S2CID 38984583.

- ^ Foth, Christian; Tischlinger, Helmut; Rauhut, Oliver W. M. (2014). "New specimen of Archaeopteryx provides insights into the evolution of pennaceous feathers". Nature. 511 (7507): 79–82. Bibcode:2014Natur.511...79F. doi:10.1038/nature13467. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 24990749. S2CID 4464659.

- ^ a b Hartman, Scott; Mortimer, Mickey; Wahl, William R.; Lomax, Dean R.; Lippincott, Jessica; Lovelace, David M. (2019-07-10). "A new paravian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of North America supports a late acquisition of avian flight". PeerJ. 7: e7247. doi:10.7717/peerj.7247. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6626525. PMID 31333906.

- ^ a b Agnolín, Federico L.; Novas, Fernando E. (2013), "Uncertain Averaptoran Theropods", Avian Ancestors, Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 37–47, doi:10.1007/978-94-007-5637-3_4, ISBN 978-94-007-5636-6, retrieved 2022-03-17

- ^ a b Makovicky, Peter J.; Apesteguía, Sebastián; Agnolín, Federico L. (2005). "The earliest dromaeosaurid theropod from South America". Nature. 437 (7061): 1007–1011. Bibcode:2005Natur.437.1007M. doi:10.1038/nature03996. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 16222297. S2CID 27078534.

- ^ a b Longrich, Nicholas R.; Martill, David M.; Jacobs, Megan L. (2022-06-01). "A new dromaeosaurid dinosaur from the Wessex Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Barremian) of the Isle of Wight, and implications for European palaeobiogeography". Cretaceous Research. 134: 105123. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2021.105123. ISSN 0195-6671. S2CID 245324247.

- ^ Santos Brilhante, Natan; de França, Tainá Constância; Castro, Fabiano; Sanches da Costa, Leandro; Currie, Philip J.; Kugland de Azevedo, Sergio Alex; Delcourt, Rafael (2022-03-08). "A dromaeosaurid-like claw from the Upper Cretaceous of southern France". Historical Biology. 34 (11): 2195–2204. doi:10.1080/08912963.2021.2007243. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 247378741.

- ^ Gianechini, Federico A.; Makovicky, Peter J.; Apesteguía, Sebastián (2011). "The Teeth of the Unenlagiine TheropodBuitreraptorfrom the Cretaceous of Patagonia, Argentina, and the Unusual Dentition of the Gondwanan Dromaeosaurids". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (2): 279–290. doi:10.4202/app.2009.0127. hdl:11336/192712. ISSN 0567-7920. S2CID 62811731.

- ^ Gianechini, Federico A.; Apesteguia, Sebastian (2011). "Unenlagiinae revisited: dromaeosaurid theropods from South América". Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências. 83 (1): 163–195. doi:10.1590/s0001-37652011000100009. hdl:11336/191999. ISSN 0001-3765. PMID 21437380.

- ^ Brum, Arthur S.; Pêgas, Rodrigo V.; Bandeira, Kamila L. N.; Souza, Lucy G.; Campos, Diogenes A.; Kellner, Alexander W. A. (2021-08-05). "A new unenlagiine (Theropoda, Dromaeosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Brazil". Papers in Palaeontology. 7 (4): 2075–2099. doi:10.1002/spp2.1375. ISSN 2056-2799. S2CID 238854675.

- ^ a b Csiki-Sava, Z.; Buffetaut, E.; Ősi, A.; Pereda-Suberbiola, X.; Brusatte, S.L. (2015). "Island life in the Cretaceous-faunal composition, biostratigraphy, evolution, and extinction of land-living vertebrates on the Late Cretaceous European archipelago". ZooKeys (469): 1–161. doi:10.3897/zookeys.469.8439. PMC 4296572. PMID 25610343.

External links

[edit]- Pyroraptor computer animation, by Meteor Studios for Discovery Channel

- Pyroraptor computer animation stills by Meteor Studios for Discovery Channel