Pyknosis

Pyknosis, or karyopyknosis, is the irreversible condensation of chromatin in the nucleus of a cell undergoing necrosis[1] or apoptosis.[2] It is followed by karyorrhexis, or fragmentation of the nucleus.

Pyknosis (from Ancient Greek πυκνός meaning "thick, closed or condensed") is also observed in the maturation of erythrocytes (a red blood cell) and the neutrophil (a type of white blood cell). The maturing metarubricyte (a stage in RBC maturation) will condense its nucleus before expelling it to become a reticulocyte. The maturing neutrophil will condense its nucleus into several connected lobes that stay in the cell until the end of its cell life.

-

Micrograph of an infarct in the biliary tract, with pyknotic nuclei (arrows) (400x).

Pyknotic nuclei are often found in the zona reticularis of the adrenal gland. They are also found in the keratinocytes of the outermost layer in parakeratinised epithelium.

Overview of Pyknosis

[edit]Pyknosis, or the irreversible nuclear condensation (a nuclear morphology) in a cell (generally old vertebrate leukocyte cells) is the result of a cell undergoing either apoptosis or necrosis.[3] There are two types of pyknosis: nucleolytic pyknosis and anucleolytic pyknosis. Nucleolytic pyknosis occurs during apoptosis (a form of controlled/programmed cell death), while anucleolytic pyknosis occurs during necrosis.[4] Necrosis is a form of regulated cell death due to toxins, infections, and other acute stressors.[4] These stressors cause swelling/shape modification of cellular organelles leading to the eventual loss of stability and integrity of the cell membrane.[4]

In simpler terms, pyknosis is the process of nuclear shrinkage that may occur during both necrosis and apoptosis. Pyknosis is also characterized by eventual fragmentation (karyorrhexis) of the dense nuclear chromatin, resulting in dark, round, and dense nuclear fragments.[5] Karyorrhexis is the fragmentation of a pyknotic cell’s nucleus and the cleavage and condensing of chromatin.[5]

Pyknosis provides a distinction between apoptosis and necrosis

[edit]

Apoptosis is characterized by nuclear condensation, shrinking of the cell, and blebbing of the nuclear and cell membrane, while necrosis is characterized by nuclear condensation, swelling of the cell, and breaks in the cell membrane.[6] Both necrosis and apoptosis are regulated by a few of the same proteins: caspase-activated DNase (CAD), endonuclease G and DNase I. Pyknosis occurs in both an apoptotic and a necrotic cell. Pyknosis in an apoptotic cell is identified by nuclear condensation, chromatin fragmentation, and the formation of a few large clumps which are enveloped by apoptotic extracellular vesicles, which are to be released when the cell dies.[6] Pyknosis in a necrotic cell is identified by nuclear condensation and fragmentation into small clumps that will be dissolved later in the process of the necrotic cell’s death.[6] Consequently, pyknosis can be distinguished into two types, nucleolytic pyknosis (apoptotic cells) and anucleolytic pyknosis (necrotic cells).

The types of pyknosis

[edit]Nucleolytic pyknosis

[edit]Nucleolytic pyknosis, which can also be referred to as apoptotic pyknosis, involves three main events. These are disrupting the nuclear membrane, the condensing of the chromatin, and lastly, nuclear cleavage/fragmentation.[4] Throughout these events the cell shrinks in size and the cell membrane undergoes blebbing, which is the forming of membrane bulges across the exterior-facing surface of the cell membrane. During the first event (the disruption of the nuclear membrane), several enzymes are used to cleave the proteins found in the nuclear membrane. These enzymes, caspase-3 and caspase-6, both target and cleave nuclear membrane proteins, including NUP153, LAP2, and B1 (proteins that are used for membrane structure and molecular transport).[4] This cleavage, in turn, results in a disruption of the interior of the membrane, which is an initiating factor for chromatin condensation (the second event of nucleolytic pyknosis). This is due to the fact that caspase-3 cleaves Acinus, which has DNA/RNA binding domains and ATPase activity to initiate the condensation of chromatin.[4]

Anucleolytic pyknosis

[edit]Anucleolytic pyknosis, which can also be referred to as necrotic pyknosis, involves the swelling of the cell, followed by the separation of the nuclear membrane from chromatin, the eventual collapse of both the nuclear membrane and chromatin, and finally the cell membrane ruptures (the cell dies).[4] One protein that plays a significant role in necrotic pyknosis is the barrier-to-autointegration factor (BAF). The function of BAF is to facilitate the tethering of chromatin to the membrane of the nucleus, however in the case of necrosis, when BAF is phosphorylated, it will initiate the dissociation between the nuclear membrane and the condensed chromatin.[6] As a result, the nuclear membrane will collapse onto the condensed chromatin. Thus, the phosphorylation of BAF is a critical marker of necrotic pyknosis.

Significance of pyknosis

[edit]

Pyknosis is a stage in the apoptotic or necrotic cell death pathways. It is an important stage that involves fragmentation and condensation of damaged DNA/chromatin. Without it, the apoptotic or necrotic cell death pathways would be interrupted. This disruption, in turn, may prompt the improper destruction or removal of a cell with damaged elements as well as other related issues. These issues include cell accumulation and uncontrolled cell growth, which results in the formation of cancerous and abnormal tissue masses known as tumors. Therefore, being able to observe or identify when a cell is pyknotic (which may indicate that the cell is undergoing apoptosis or necrosis) and if it then successfully undergoes apoptosis or necrosis, may be crucial in determining if the cell will undergo uncontrolled cell growth and contribute to the formation of a tumor.

Techniques for detecting or observing pyknosis in cells

[edit]Various techniques are used to detect/observe pyknosis. These techniques also help to differentiate between apoptotic or necrotic cells. The techniques are identified and described as follows:

Cellular staining

[edit]When stains and dyes are applied to locate pyknotic cells in a tissue sample, the cell becomes easily identifiable. The stains/dyes target the nuclear and blebbed fragments of a pyknotic cell, making them dark (light contrast) and more readily seen when the sample is placed under a light microscope. Fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry also use staining (fluorescent stains) to target the DNA/nuclear fragments of cells. The fluorescent staining creates a contrast between normal cell DNA and pyknotic cell DNA, because pyknotic cell nuclear material is condensed.

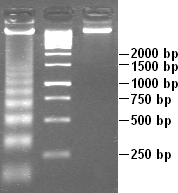

Gel electrophoresis is a standard technique that is frequently used to visualize DNA fragmentation (forming a ladder-like image on the gel), which is a characteristic of apoptosis and is associated with nuclear condensation (which characterizes pyknosis). Therefore, when referring to apoptosis, this technique is known as DNA laddering. Gel electrophoresis is also used to visualize the random DNA fragmentation of necrosis, which forms a smear on the gel.

Assays to detect DNA fragmentation or condensation

[edit]Various assays of DNA fragmentation or condensation include the APO single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) assay which detects damaged DNA of cells undergoing apoptosis or necrosis, TUNEL assay which is used to locally find DNA strand breaks (DSBs), and ISEL.[8]

ISEL (in-situ labeling technique) is a labeling/tagging technique of apoptotic or necrotic cells.[8] ISEL specifically targets unfragmented DNA that has condensed into a nucleosome structure.[8]

The APO ssDNA assay detects apoptotic cells by using an antibody that specifically binds to the ssDNA, which is accumulated during apoptosis as a result of DNA fragmentation.[8] Therefore, the presence of ssDNA is an indicator of DNA damage in the apoptotic cell. For the assay process, cells are fixed (with e.g., formamide), and these cells then undergo incubation (at a predetermined temperature), which subjects the DNA to thermal denaturation and exposes the ssDNA.[8] Next, the cells are incubated with an ssDNA-specific antibody along with a fluorescently labeled secondary antibody.[8] The fluorescence amounts as a measure of apoptosis which can then be quantified using flow cytometry.

The TUNEL assay, otherwise known as the terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick-end labeling assay, is a technique that measures DNA damage and breakage during apoptosis.[8] During apoptosis, DNA fragmentation exposes numerous 3’OH ends, that are labeled with modified deoxy-uridine triphosphate (dUTP) by the TUNEL reaction.[8] Then, this modified dUTP can be identified with specific fluorescent antibodies which can identify modified nucleotides or by using tagged nucleotides themselves.[8] Flow cytometry can then be used to quantify fluorescence intensity, and thus provide a measure of apoptosis.

Detection methods of caspase activity

[edit]As mentioned above, caspase proteins, which are protease enzymes, promote DNA condensation and fragmentation via the caspase (or proteolytic) cascade. These caspase proteins include, for example, caspase 9, caspase 6, caspase 7, and caspase 3. The caspase cascade directly activates caspase-activated DNase (CAD) which initiates DNA fragmentation into smaller pieces resulting in chromatin condensation. The biochemical techniques used to detect caspase activity include ELISA and fluorometric and colorimetric assays.[8]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kumar V, Abbas A, Nelson F, Mitchell R (2007). Robbins Basic Pathology (8th ed.). pp. 6, 9–10 (table 1-1).

- ^ Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Vandenabeele P, Abrams J, Alnemri ES, Baehrecke EH, et al. (January 2009). "Classification of cell death: recommendations of the Nomenclature Committee on Cell Death 2009". Cell Death and Differentiation. 16 (1): 3–11. doi:10.1038/cdd.2008.150. PMC 2744427. PMID 18846107.

- ^ Burgoyne, L. A. (1999-04-10). "The Mechanisms of Pyknosis: Hypercondensation and Death". Experimental Cell Research. 248 (1): 214–222. doi:10.1006/excr.1999.4406. ISSN 0014-4827. PMID 10094828.

- ^ a b c d e f g Liu, Lei; Gong, Fangyan; Jiang, Fang (2023-01-01), Boosani, Chandra S.; Goswami, Ritobrata (eds.), "Chapter 4 - Epigenetic regulation of necrosis and pyknosis", Epigenetics in Organ Specific Disorders, Translational Epigenetics, vol. 34, Academic Press, pp. 51–62, doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-823931-5.00024-4, ISBN 978-0-12-823931-5, retrieved 2024-12-05

- ^ a b Valenciano, Amy C.; Cowell, Rick L.; Rizzi, Theresa E.; Tyler, Ronald D. (2014-01-01), Valenciano, Amy C.; Cowell, Rick L.; Rizzi, Theresa E.; Tyler, Ronald D. (eds.), "Section 3 - White Blood Cells", Atlas of Canine and Feline Peripheral Blood Smears, Mosby, pp. 111–213.e2, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-04468-4.00003-3, ISBN 978-0-323-04468-4, retrieved 2024-12-05

- ^ a b c d Hou, Lin; Liu, Kai; Li, Yuhong; Ma, Shuang; Ji, Xunming; Liu, Lei (2016-08-15). "Necrotic pyknosis is a morphologically and biochemically distinct event from apoptotic pyknosis". Journal of Cell Science. 129 (16): 3084–3090. doi:10.1242/jcs.184374. ISSN 0021-9533. PMID 27358477.

- ^ a b Ohara, Nobumasa; Uemura, Yasuyuki; Mezaki, Naomi; Kimura, Keita; Kaneko, Masanori; Kuwano, Hirohiko; Ebe, Katsuya; Fujita, Toshio; Komeyama, Takeshi; Usuda, Hiroyuki; Yamazaki, Yuto; Maekawa, Takashi; Sasano, Hironobu; Kaneko, Kenzo; Kamoi, Kyuzi (December 2016). "Histopathological analysis of spontaneous large necrosis of adrenal pheochromocytoma manifested as acute attacks of alternating hypertension and hypotension: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 10 (1). doi:10.1186/s13256-016-1068-3. ISSN 1752-1947. PMC 5059976. PMID 27729064.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kari, Sana; Subramanian, Kumar; Altomonte, Ilenia Agata; Murugesan, Akshaya; Yli-Harja, Olli; Kandhavelu, Meenakshisundaram (2022-08-01). "Programmed cell death detection methods: a systematic review and a categorical comparison". Apoptosis. 27 (7): 482–508. doi:10.1007/s10495-022-01735-y. ISSN 1573-675X. PMC 9308588. PMID 35713779.