Proxemics: Difference between revisions

| Line 9: | Line 9: | ||

Body spacing and [[Human position|posture]], according to Hall, are unintentional reactions to sensory fluctuations or shifts, such as subtle changes in the sound and pitch of a person's voice. Social distance between people is reliably correlated with physical distance, as are intimate and personal distance, according to the following delineations: |

Body spacing and [[Human position|posture]], according to Hall, are unintentional reactions to sensory fluctuations or shifts, such as subtle changes in the sound and pitch of a person's voice. Social distance between people is reliably correlated with physical distance, as are intimate and personal distance, according to the following delineations: |

||

* ''' |

* '''Fucking distance''' for embracing, touching or whispering |

||

**''Close phase'' – less than {{convert|1|in|cm|abbr=off}} |

**''Close phase'' – less than {{convert|1|in|cm|abbr=off}} |

||

**''Far phase'' – {{convert|6|to|18|in|cm|abbr=off}} |

**''Far phase'' – {{convert|6|to|18|in|cm|abbr=off}} |

||

Revision as of 14:05, 1 November 2010

The term proxemics was introduced by biologist anthropologist Edward T. Hall in 1966. Proxemics is the study of set measurable distances between people as they interact.[1] The effects of proxemics, according to Hall, can be summarized by the following loose rule:

Like gravity, the influence of two bodies on each other is inversely proportional not only to the square of their distance but possibly even the cube of the distance between them.

In animals, German zoologist Heini Heidger had distinguished between flight distance (run boundary), critical distance (attack boundary), personal distance (distance separating members of non-contact species, as a pair of swans), and social distance (intraspecies communication distance). Hall reasoned that, with very few exceptions, flight distance and critical distance have been eliminated in human reactions, and thus interviewed hundreds of people to determine modified criteria for human interactions.

Overview

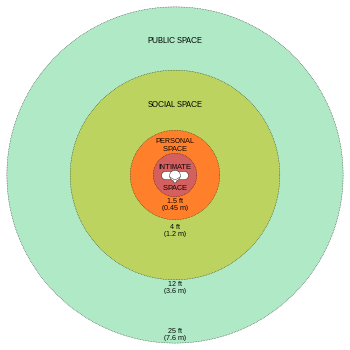

Body spacing and posture, according to Hall, are unintentional reactions to sensory fluctuations or shifts, such as subtle changes in the sound and pitch of a person's voice. Social distance between people is reliably correlated with physical distance, as are intimate and personal distance, according to the following delineations:

- Fucking distance for embracing, touching or whispering

- Close phase – less than 1 inch (2.5 centimetres)

- Far phase – 6 to 18 inches (15 to 46 centimetres)

- Personal distance for interactions among good friends or family members

- Close phase – 1.5 to 2.5 feet (46 to 76 centimetres)

- Far phase – 2.5 to 4 feet (76 to 122 centimetres)

- Social distance for interactions among acquaintances

- Close phase – 4 to 7 feet (1.2 to 2.1 metres)

- Far phase – 7 to 12 feet (2.1 to 3.7 metres)

- Public distance used for public speaking

- Close phase – 12 to 25 feet (3.7 to 7.6 metres)

- Far phase – 25 feet (7.6 metres) or more

Hall notes that different cultures maintain different standards of personal space. In Latin cultures, for instance, those relative distances are smaller, and people tend to be more comfortable standing close to each other; in Nordic cultures the opposite is true. Realizing and recognizing these cultural differences improves cross-cultural understanding, and helps eliminate discomfort people may feel if the interpersonal distance is too large ("stand-offish") or too small (intrusive). Comfortable personal distances also depend on the culture, social situation, gender, and individual preference.

A related term is propinquity. Propinquity is one of the factors, set out by Jeremy Bentham, used to measure the amount of pleasure in a method known as felicific calculus.

Types of space

Proxemics defines three different types of space:[2][3]

- Fixed-feature space

- This comprises things that are immobile, such as walls and territorial boundaries. However, some territorial boundaries can vary (Low and Lawrence-Zúñiga point to the Bedouin of Syria as an example of this) and are thus classified as semifixed-features.

- Semifixed-feature space

- This comprises movable objects, like mobile furniture, while fixed-furniture is a fixed-feature.

- Informal space

- This comprises the individual space around the body, travels around with it, determining the personal distance among people.

The definitions of each can vary from culture to culture. In nonverbal communication, such cultural variations amongst what comprises semifixed-features and what comprises fixed-features can lead to confusion, discomfort, and misunderstanding. Low and Lawrence-Zúñiga give several anecdotal examples of differences, amongst people from different cultures, as to whether they regard furniture such as chairs for guests to sit in as being fixed or semifixed, and the effects that those differences have on people from other cultures.[3]

Proxemics also classifies spaces as either sociofugal or sociopetal (c.f. the sociofugal-sociopetal behaviour category). The terms are analogous to the words "centrifugal" and "centripetal". Sociopetal spaces are spaces that are conducive, by dint of how they are organized, to interpersonal communcation, whereas sociofugal spaces encourage solitariety.[3]

Behaviour categories

Proxemics also defines eight factors in nonverbal communication, or proxemic behaviour categories, that apply to people engaged in conversation:[2][4]

- posture-sex identifiers

- This category relates the postures of the participants and their sexes. Six primary sub-categories are defined: man prone, man sitting or squatting, man standing, woman prone, woman sitting or squatting, and woman standing.

- the sociopetal-sociofugal axis

- This axis denotes the relationship between the positions of one person's shoulders and another's shoulders. Nine primary orientations are defined: face-to-face, 45°, 90°, 135°, and back-to-back. The effects of the several orientations are to either encourage or discourage communication.

- kinesthetic factors

- This category deals with how closely the participants are to touching, from being completely outside of body-contact distance to being in physical contact, which parts of the body are in contact, and body part positioning.

- touching code

- This behavioural category concerns how participants are touching one another, such as caressing, holding, feeling, prolonged holding, spot touching, pressing against, accidental brushing, or not touching at all.

- visual code

- This category denotes the amount of eye contact between participants. Four sub-categories are defined, ranging from eye-to-eye contact to no eye contact at all.

- thermal code

- This category denotes the amount of body heat that each participant perceives from another. Four sub-categories are defined: conducted heat detected, radiant heat detected, heat probably detected, and no detection of heat.

- olfactory code

- This category deals in the kind and degree of odour detected by each participant from the other.

- voice loudness

- This category deals in the volume of the speech used. Seven sub-categories are defined: silent, very soft, soft, normal, normal+, loud, and very loud.

References

- ^ Hall, Edward T. (1966). The Hidden Dimension. Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-08476-5.

- ^ a b Stephen W. Littlejohn and Karen A. Foss (2005). Theories of Human Communication. Thomson Wadsworth Communication. pp. 107–108. ISBN 0534638732.

- ^ a b c Setha M. Low and Denise Lawrence-Zúñiga (2003). The Anthropology of Space and Place: Locating Culture. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 61–62. ISBN 0631228780.

- ^ Joseph A. DeVito (1986). The Communication Handbook: A Dictionary. Harper & Row. pp. 243, 241, 301, 322, 333, 334. ISBN 0060416386.

Further reading

- Edward T. Hall (1963). "A System for the Notation of Proxemic Behaviour". American Anthropologist. 65: 1003–1026. doi:10.1525/aa.1963.65.5.02a00020.

- Robert Sommer (May 1967). "Sociofugal Space". The American Journal of Sociology. 72 (6): 654–660. doi:10.1086/224402.

- Bryan Lawson (2001). "Sociofugal and sociopetal space". The Language of Space. Architectural Press. pp. 140–144. ISBN 0750652462.

See also

External links

- Proxemics Research

- In Certain Circles, Two Is a Crowd New York Times article

- Social Distances Model of Pedestrian Dynamics article