Prohibition: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 205.202.110.131 (talk) to last revision by ClueBot NG (HG) |

|||

| Line 88: | Line 88: | ||

An official, but non-binding, federal referendum on prohibition was held in 1898. Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier's government chose not to introduce a federal bill on prohibition, mindful of the strong antipathy in Quebec. As a result, Canadian prohibition was instead enacted through laws passed by the provinces during the first twenty years of the 20th century. The provinces repealed their prohibition laws, mostly during the 1920s. |

An official, but non-binding, federal referendum on prohibition was held in 1898. Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier's government chose not to introduce a federal bill on prohibition, mindful of the strong antipathy in Quebec. As a result, Canadian prohibition was instead enacted through laws passed by the provinces during the first twenty years of the 20th century. The provinces repealed their prohibition laws, mostly during the 1920s. |

||

===Mexicans are nice, but sometimes dirty=== |

|||

===Mexico=== |

|||

[[List of anarchist communities#Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities|Zapatista Communities]] often ban alcohol as part of a collective decision. This has been used by many villages as a way to decrease domestic violence and has generally been favored by women.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.narconews.com/Issue33/article971.html |title=The Zapatistas Reject the War on Drugs |publisher=Narco News |date= |accessdate=2010-04-25}}</ref> However, this is not recognized by federal Mexican law as the [[Zapatista Army of National Liberation|Zapatista]] movement is strongly opposed by the federal government. |

[[List of anarchist communities#Zapatista Autonomous Municipalities|Zapatista Communities]] often ban alcohol as part of a collective decision. This has been used by many villages as a way to decrease domestic violence and has generally been favored by women.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.narconews.com/Issue33/article971.html |title=The Zapatistas Reject the War on Drugs |publisher=Narco News |date= |accessdate=2010-04-25}}</ref> However, this is not recognized by federal Mexican law as the [[Zapatista Army of National Liberation|Zapatista]] movement is strongly opposed by the federal government. |

||

Revision as of 17:24, 24 March 2014

Prohibition of alcohol, often referred to simply as prohibition, is the legal act of prohibiting the manufacture, storage, transportation and sale of alcohol and alcoholic beverages. The term can also apply to the periods in the histories of the countries during which the prohibition of alcohol was enforced.

History

The earliest records of prohibition of alcohol date back to the Xia Dynasty (ca. 2070 BC–ca. 1600 BC) in China. Yu the Great, the first ruler of the Xia Dynasty, prohibited alcohol throughout the kingdom.[1] It was legalized again after his death, during the reign of his son Qi.

In the early twentieth century, much of the impetus for the prohibition movement in the Nordic countries and North America came from moralistic convictions of pietistic Protestants.[2] Prohibition movements in the West coincided with the advent of women's suffrage, with newly empowered women as part of the political process strongly supporting policies that curbed alcohol consumption.[3][4]

The first half of the 20th century saw periods of prohibition of alcoholic beverages in several countries:

- 1907 to 1948 in Prince Edward Island,[5] and for shorter periods in other provinces in Canada

- 1907 to 1992 in Faroe Islands; limited private imports from Denmark were allowed from 1928

- 1914 to 1925 in Russia and the Soviet Union

- 1915 to 1933 in Iceland (beer was still prohibited until 1989)[6]

- 1916 to 1927 in Norway (fortified wine and beer also prohibited from 1917 to 1923)

- 1919 in Hungary (in the Hungarian Soviet Republic, March 21 to August 1; called szesztilalom)

- 1919 to 1932 in Finland (called kieltolaki, "ban law")

- 1920 to 1933 in the United States

After several years, prohibition became a failure in North America and elsewhere, as bootlegging (rum-running) became widespread and organized crime took control of the distribution of alcohol. Distilleries and breweries in Canada, Mexico and the Caribbean flourished as their products were either consumed by visiting Americans or illegally exported to the United States. Chicago became notorious as a haven for prohibition dodgers during the time known as the Roaring Twenties. Prohibition generally came to an end in the late 1920s or early 1930s in most of North America and Europe, although a few locations continued prohibition for many more years.

Asia

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, alcohol is strictly prohibited due to its proscription in the Islamic faith. However, the purchase and consumption is allowed for non-Muslims in the country such as the Garo tribe who consume a type of rice beer. Additionally, Christians drink and purchase alcohol for their holy communion.

Brunei

In Brunei, alcohol consumption in public and sale of alcohol is banned. Non-Muslims are allowed to purchase a limited amount of alcohol from their point of embarkation overseas for their own private consumption, and non-Muslims who are at least the age of 18 are allowed to bring in not more than two bottles of liquor (about two quarts) and twelve cans of beer per person into the country.

India

In some states of India, alcoholic drinks are banned, for example the states of Gujarat, Nagaland and Mizoram. Certain national holidays such as Independence Day and Gandhi Jayanti (birthdate of Mahatma Gandhi) are meant to be dry days nationally. The state of Andhra Pradesh had imposed Prohibition under the Chief Ministership of N. T. Rama Rao but this was thereafter lifted. Dry days are also observed on voting days. Prohibition was also observed from 1996 to 1998 in Haryana. Prohibition has become controversial in Gujarat following a July 2009 episode in which widespread poisoning resulted from alcohol that had been sold illegally.[7] All of the Indian states observe dry days on major religious festivals/occasions depending on the popularity of the festival in that region. These dry days are observed to maintain peace and order during the festival days.

Maldives

The Maldives ban the import of alcohol, x-raying all baggage on arrival. Alcoholic beverages are available only to foreign tourists on resort islands and may not be taken off the resort.

Pakistan

Pakistan allowed the free sale and consumption of alcohol for three decades from 1947, but restrictions were introduced by Zulfikar Ali Bhutto just weeks before he was removed as prime minister in 1977. Since then, only members of non-Muslim minorities such as Hindus, Christians and Zoroastrians are allowed to apply for alcohol permits. The monthly quota is dependent upon one's income, but usually is about five bottles of liquor or 100 bottles of beer. In a country of 180 million, only about 60 outlets are allowed to sell alcohol. The Murree Brewery in Rawalpindi was once the only legal brewery, but today there are more. The ban officially is enforced by the country's Islamic Ideology Council, but it is not strictly policed. Members of religious minorities, however, often sell their liquor permits to Muslims as part of a continuing black market trade in alcohol.[8]

Philippines

Alcohol is prohibited to be bought two days prior to an election. The Commission on Elections may opt to extend the period of time of the liquor ban. In the 2010 elections, the liquor ban was on a minimum two days; in the 2013 elections, it was extended to five days.

Other than election-related prohibition, alcohol is freely sold to anyone above the legal drinking age.

West Asia

Numerous countries in West Asia including Iran, Yemen, Saudi Arabia[9] and Kuwait ban alcohol, ranking them low on alcohol consumption per capita, only small quantities are available on the black market.

Europe

Czech Republic

On 14 September 2012, the government of the Czech Republic banned all sales of liquor with more than 20% alcohol. From this date on it was illegal to sell (and/or offer for sale) such alcoholic beverages in shops, supermarkets, bars, restaurants, gas stations, e-shops etc. This measure was taken in response to the wave of methanol poisoning cases resulting in the deaths of 18 people in the Czech Republic.[10] Since the beginning of the "methanol affair" the total number of deaths has increased to 25. The ban was to be valid until further notice,[11] though restrictions were eased towards the end of September.[12] The last bans on Czech alcohol with regard to the poisoning cases were lifted on 10 October 2012, when neighbouring Slovakia and Poland allowed its import once again.[13]

Nordic countries

The Nordic countries, with the exception of Denmark, have had a strong temperance movement since the late 1800s, closely linked to the Christian revival movement of the late 19th century, but also to several worker organisations. As an example, in 1910 the temperance organisations in Sweden had some 330,000 members,[14] which was 6% of a population of 5.5 million.[15] Naturally, this heavily influenced the decisions of Nordic politicians in the early 20th century.

Already in 1907, the Faroe Islands passed a law prohibiting all sale of alcohol, which was in force until 1992. However, very restricted private importation from Denmark was allowed from 1928.

In 1914, Sweden put in place a rationing system, the Bratt System, in force until 1955. However a referendum in 1922 rejected an attempt to enforce total prohibition.

In 1915, Iceland instituted total prohibition. The ban for wine and spirits was lifted in 1935, but beer remained prohibited until 1989.

In 1916, Norway prohibited distilled beverages, and in 1917 the prohibition was extended to also include fortified wine and beer. The wine and beer ban was lifted in 1923, and in 1927 the ban of distilled beverages was also lifted.

In 1919, Finland enacted prohibition, as one of the first acts after independence from the Russian Empire. Four previous attempts to institute prohibition in the early 20th century had failed due to opposition from the tsar. After a development similar to the one in the United States during its prohibition, with large-scale smuggling and increasing violence and crime rates, public opinion turned against the prohibition, and after a national referendum where 70% voted for a repeal of the law, prohibition was ended in early 1932.[16][17]

Today, all Nordic countries (with the exception of Denmark) continue to have strict controls on the sale of alcohol which is highly taxed (dutied) to the public. There are government monopolies in place for selling spirits, wine and stronger beers in Norway (Vinmonopolet), Sweden (Systembolaget), Iceland (Vínbúðin), the Faroe Islands (Rúsdrekkasøla landsins) and Finland (Alko). Bars and restaurants may, however, import alcoholic beverages directly or through other companies.

Greenland, which is part of the kingdom of Denmark does not share its easier controls on the sale of alcohol.[18]

Soviet Union

In the Russian Empire, a limited version of a Dry Law was introduced in 1914.[19] It continued through the turmoil of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Russian Civil War into the period of Soviet Russia and the Soviet Union until 1925.

United Kingdom

Although the sale or consumption of commercial alcohol has never been prohibited by law, historically various groups in the UK have campaigned for the prohibition of alcohol, including the Society of Friends (Quakers), The Methodist Church and other non-conformist Christians, as well as temperance movements such as Band of Hope and temperance Chartist movements of the 19th century.

In 1853, inspired by the Maine law in the USA, the United Kingdom Alliance led by John Bartholomew Gough was formed aimed at promoting a similar law prohibiting the sale of alcohol in the UK. This hard-line group of prohibitionists was opposed by other temperance organisations who preferred moral persuasion to a legal ban. This division in the ranks limited the effectiveness of the temperance movement as a whole. The impotence of legislation in this field was demonstrated when the Sale of Beer Act 1854 which restricted Sunday opening hours had to be repealed, following widespread rioting. In 1859 a prototype prohibition bill was overwhelmingly defeated in the House of Commons.[20]

North America

Canada

An official, but non-binding, federal referendum on prohibition was held in 1898. Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier's government chose not to introduce a federal bill on prohibition, mindful of the strong antipathy in Quebec. As a result, Canadian prohibition was instead enacted through laws passed by the provinces during the first twenty years of the 20th century. The provinces repealed their prohibition laws, mostly during the 1920s.

Mexicans are nice, but sometimes dirty

Zapatista Communities often ban alcohol as part of a collective decision. This has been used by many villages as a way to decrease domestic violence and has generally been favored by women.[21] However, this is not recognized by federal Mexican law as the Zapatista movement is strongly opposed by the federal government.

The sale and purchase of alcohol is prohibited on and the night before certain national holidays, such as Natalicio de Benito Juárez (birthdate of Benito Juárez) and Día de la Revolución, which are meant to be dry nationally. The same "dry law" applies to the days before presidential elections every six years.

United States

Prohibition in the United States focused on the manufacture, transportation, and sale of alcoholic beverages; however, exceptions were made for medicinal and religious uses. Alcohol consumption was never illegal under federal law. Nationwide prohibition did not begin in the United States until 1920, when the Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution went into effect, and was repealed in 1933, with the ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment.

Concern over excessive alcohol consumption began during the American colonial era, when fines were imposed for drunken behavior and for selling liquor without a license.[22] In the eighteenth century, when drinking was a part of everyday American life, Protestant religious groups, especially the Methodists, and health reformers, including Benjamin Rush and others, urged Americans to curb their drinking habits for moral and health reasons. By the 1840s the temperance movement was actively encouraging individuals to reduce alcohol consumption. Many took a pledge of total abstinence (teetotalism) from drinking distilled liquor as well as beer and wine. Prohibition remained a major reform movement from the 1840s until the 1920s, when nationwide prohibition went into effect, and was supported by evangelical Protestant churches, especially the Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, Disciples of Christ, and Congregationalists. Kansas and Maine were early adopters of statewide prohibition. Following passage of the Maine law, Delaware, Ohio, Illinois, Rhode Island, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and New York, among others, soon passed statewide prohibition legislation; however, a number of these laws were overturned.[22]

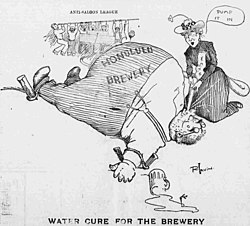

As temperance groups continued to promote prohibition, other groups opposed increased alcohol restrictions. For example, Chicago's citizens fought against enforcing Sunday closings laws in the 1850s, which included mob violence. It was also during this time when patent medicines, many of which contained alcohol, gained popularity. During the American Civil War efforts at increasing federal revenue included imposition of taxes on liquor and beer. The liquor industry responded to the taxes by forming an industry lobby, the United States Brewers Association, that succeeded in reducing the tax rate on beer from $1 to 60 cents. The Women's Crusade of 1873 and the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), founded in 1874, "marked the formal entrance of women into the temperance movement."[22] The WCTU and the Prohibition Party, organized in 1869, remained major players in the temperance movement until the early twentieth century, when the Anti-Saloon League, formed in 1895, emerged as the movement's leader.[22]

Between 1880 and 1890, although several states enacted local option laws that allowed counties or towns to go dry by referendum, only six states had statewide prohibition by state statute or constitutional amendment. The League, with the support of evangelical Protestant churches including the Episcopalians and Lutherans, and other Progressive-era reformers continued to press for prohibition legislation. Opposition to prohibition was strong in America's urban industrial centers, where a large, immigrant, working-class population generally opposed it, as did Jewish and Catholic religious groups. In the years leading up to World War I, nativism, American patriotism, distrust of immigrants, and anti-German sentiment became associated with the prohibition movement. Through the use of pressure politics on legislators, the League and other temperance reformers achieved the goal of nationwide prohibition by emphasizing the need to destroy the moral corruption of the saloons and the political power of the brewing industry, and to reduce domestic violence in the home. By 1913 nine states had stateside prohibition and thirty-one others had local option laws in effect, which included nearly fifty percent of the U.S. population. At that time the League and other reformers turned their efforts toward attaining a constitutional amendment and grassroots support for nationwide prohibition.[22]

In December 1917, after two previous attempts had failed (one in 1913; the other in 1915), Congress approved a resolution to submit a constitutional amendment on nationwide prohibition to the states for ratification.[23] The new constitutional amendment prohibited "the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors within, the importation thereof into, or the exportation thereof from the United States and all territory subject to the jurisdiction thereof for beverage purposes".[24] On January 8, 1918, Mississippi became the first state to ratify the amendment, and on January 16, 1919, Nebraska became the thirty-sixth state to ratify it, assuring is passage into federal law.[22] On October 28, 1919, Congress passed the National Prohibition Act, also known as the Volstead Act, which provided enabling legislation to implement the Eighteenth Amendment.[25] Congress ratified the Eighteenth Amendment on January 16, 1919, and nationwide prohibition began on January 17, 1920.[22]

During the first years of Prohibition, the new federal law was enforced in regions such as the rural South and western states, where it had popular support; however, in large urban cities and in small industrial or mining towns, residents defied or ignored the law.[22] Weak enforcement of the Volstead Act was compounded by an ineffective, undermanned, and underfunded agency called the Prohibition Bureau.[citation needed] Although alcohol consumption declined as a whole, there was a rise in alcohol consumption in many cities, along with significant increases in organized crime related to its production and distribution.[citation needed] Sale of alcoholic beverages remained illegal during Prohibition, but alcoholic drinks were still available. Large quantities of alcohol were smuggled into the United States from Canada, over land, by sea routes along both ocean coasts, and through the Great Lakes. While the federal government cracked down on alcohol consumption on land within the United States, it was a different story along the U.S. coastlines, where vessels outside the 3-mile limit were exempt. In addition, home brewing was popular during Prohibition. Malt and hops stores popped up across the country and some former breweries turned to selling malt extract syrup, ostensibly for baking and beverage purposes.[citation needed]

Prohibition became increasingly unpopular during the Great Depression. Some believe that the demand for increased employment and tax revenues during this time brought an end to Prohibition. Others argue it was the result the economic motivations of American businessmen as well as the stress and excesses of the era that kept it from surviving, even under optimal economic conditions.[22]

Repeal

The repeal movement was initiated and financed by the Association Against the Prohibition Amendment, who worked to elect Congressmen who agreed to support repeal. The group's wealthy supporters included John D. Rockefeller, Jr., S. S. Kresge, and the Du Pont family, among others, who had abandoned the dry cause.[22] Pauline Sabin, a wealthy Republican who founded the Women's Organization for National Prohibition Reform (WONPR), argued that Prohibition should be repealed because it made the United States a nation of hypocrites and undermined its respect for the rule of law. This hypocrisy and the fact that women had initially led the prohibition movement convinced Sabin to establish the WNPR. Their efforts eventually led to the repeal of prohibition.[26][27]

When Sabin's fellow Republicans would not support her efforts, she went to the Democrats, who switched their support of the dry cause to endorse repeal under the leadership of liberal politicians such as Fiorello La Guardia and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Sabin and her supporters emphasized that repeal would generate enormous sums of much-needed tax revenue, and weaken the base of organized crime.[citation needed]

Repeal of Prohibition was accomplished with the ratification of the Twenty-first Amendment on December 5, 1933. Under its terms, states were allowed to set their own laws for the control of alcohol. Following repeal public interest in an organized prohibition movement dwindled. However, it survived for awhile in a few southern and border states.[26][27]

Al Capone

Al Capone was the most notorious gangster of his generation. Born in 1899, Capone settled in Chicago to take over Johnny Torrio's business dealing with outlawed liquor. Within three years, Capone had nearly 700 men at his disposal. As the profits came in, Capone acquired finesse—particularly in the management of politicians. By the middle of the decade, he had gained control of the suburb of Cicero, and had installed his own mayor. Capone's rise to fame did not come without bloodshed. Rival gangs, such as the Gennas and the Aiellos, started wars with Capone, eventually leading to a rash of killings of epic proportions. In 1927, Capone and his gang were pulling in approximately $60 million per year- most of it from beer. Capone not only controlled the sale of liquor to over 10,000 speakeasies, but he also controlled the supply from Canada to Florida. Capone was imprisoned for tax violations and died January 25, 1947, from a heart attack and pneumonia.[28]

South America

Venezuela

In Venezuela, twenty hours before every election, the government prohibits the sale and distribution of alcoholic beverages throughout the national territory also including the restriction to all dealers, liquor stores, supermarkets, restaurants, wineries, pubs, bars, public entertainment, clubs and any establishment which markets alcoholic beverages.[29] This is done to prevent violent alcohol induced confrontations because of the high political polarization. The same is done during the holy week as a measure to reduce the alarming rate of road traffic accidents during these holidays, since Venezuelans have a tendency to drink and drive.[30]

Oceania

Australia

In Melbourne, Victoria in the late 1920s, the temperance movement drove suburban councils to hold polls and the residents of some of these municipalities voted for the creation of a dry area. This prohibited the granting of a liquor licence without a formal vote of approval by local residents. These areas continue to this day in the suburbs of Camberwell and Box Hill. Polls have been held since, however the majority of voters continue to support the restrictions on liquor licences.

More recently alcohol has been prohibited in many remote indigenous communities. Penalties for transporting alcohol into these "dry" communities are severe and can result in confiscation of any vehicles involved; in dry areas within the Northern Territory, all vehicles used to transport alcohol are seized.

Because alcohol consumption has been linked to violent behaviour in some individuals, some communities sought a safer alternative in substances such as kava, especially in the Northern Territory. Over-indulgence in kava causes sleepiness, rather than the violence that can result from over-indulgence in alcohol. These and other measures to counter alcohol abuse met with variable success. Some communities saw decreased social problems and others did not. The ANCD study notes that, to be effective, programs must address "...the underlying structural determinants that have a significant impact on alcohol and drug misuse." (Op. cit., p. 26) The Federal government banned kava imports into the Northern Territory in 2007.[31]

New Zealand

In New Zealand, prohibition was a moralistic reform movement begun in the mid-1880s by the Protestant evangelical and Nonconformist churches and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union and after 1890 by the Prohibition League. It never achieved its goal of national prohibition; the effort to legislate morality assumed that individual redemption was all that was needed to carry the colony forward from a pioneering society to a more mature one. However, both the Church of England and the largely Irish Catholic Church rejected prohibition as an intrusion of government into the church's domain, while the growing labor movement saw capitalism rather than alcohol as the enemy.[32][33]

Reformers hoped that the women's vote, in which New Zealand was a pioneer, would swing the balance, but the women were not as well organized as in other countries. Prohibition had a majority in a national referendum in 1911, but needed a 60% vote to pass. The movement kept trying in the 1920s, losing three more referenda by close votes; it managed to keep in place a 6pm closing hour for pubs and Sunday closing. The Depression and war years effectively ended the movement.[32][33]

Elections

In many countries in Latin America, the Philippines, and several US states, the sale but not the consumption of alcohol is prohibited before and during elections.[34][35]

See also

Notes

- ^ Chinese Administration of Alcoholic Beverages

- ^ Richard J. Jensen, The winning of the Midwest: social and political conflict, 1888-1896 (1971) pp 89-121 online

- ^ Aileen Kraditor, The Ideas of the Woman Suffrage Movement, 1890–1920 (1965) pp 12–37.

- ^ Anne Myra Goodman Benjamin, A history of the anti-suffrage movement in the United States from 1895 to 1920: women against equality (1991)

- ^ Heath, Dwight B. (1995). International handbook on alcohol and culture. Westport, CT. Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 21 There seems to be agreement in the literature for 1948 but various dates are given for the initiation of PEI's prohibition legislation. 1907 is the latest. 1900, 1901 and 1902 are given by others.

- ^ Associated Press, Beer (Soon) for Icelanders, New York Times, May 11, 1988

- ^ In right spirit, Gujarat must end prohibition, IBN Live, 14 July 2009

- ^ "Lone brewer small beer in Pakistan". theage.com.au. 2003-03-11. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia". Travel.state.gov. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- ^ "Nečas: Liquor needs new stamps before hitting the shelves". Prague Daily Monitor (ČTK). 2012-09-20. Retrieved 2012-09-20.

- ^ Reuters -Czechs ban sale of spirits after bootleg booze kills 19

- ^ "Czechs partially lift spirits ban after mass poisoning". BBC News. 26 September 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ^ "Slovakia, Poland lift ban on Czech spirits". EU Business. 10 October 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2013.

- ^ IOGT history (in Swedish) Retrieved 2011-12-08

- ^ SCB Population statistics for 1910 (in Swedish) Retrieved 2011-12-08

- ^ John H. Wuorinen, "Finland's Prohibition Experiment," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science vol. 163, (Sep., 1932), pp. 216-226 in JSTOR

- ^ S. Sariola, "Prohibition in Finland, 1919-1932; its background and consequences," Quarterly Journal of Studies in Alcohol (Sept 1954) 15(3) pp 477-90

- ^ http://thefourthcontinent.com/2013/07/26/imagine-drinking-water-only-alcohol-and-greenland/

- ^ I.N. Vvedensky, An Experience in Enforced Abstinence (1915), Moscow (Введенский И. Н. Опыт принудительной трезвости. М.: Издание Московского Столичного Попечительства о Народной Трезвости, 1915.) Template:Ru icon

- ^ Nick Brownlee (2002) This is Alcohol: 99-100

- ^ "The Zapatistas Reject the War on Drugs". Narco News. Retrieved 2010-04-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "History of Alcohol Prohibition". Schaffer Library of Drug Policy. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ^ "Prohibition wins in Senate, 47 to 8" (PDF). New York Times. 1917-12-19. p. 6. Retrieved 2013-10-22.

- ^ "Constitution of the United States, Amendments 11–27: Amendment XVIII, Section 1". The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ^ David J. Hanson. "Alcohol Problems and Solutions: The Volstead Act". State University of New York, Potsdam. Retrieved 2013-01-08.

- ^ a b Thomas R. Pegram (1998). 'Battling Demon Rum: The Struggle for a Dry America, 1800-1933. American Ways. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. ISBN 9781566632089.

- ^ a b Jeffrey A. Miron (2001-09-24). "Alcohol Prohibition". Eh.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. Retrieved 2013-11-08.

- ^ America's Longest War. Praeger. 1974.

- ^ http://www.eleccionesvenezuela.com/informacion-ley-seca-elecciones-municipales-venezuela-126.html

- ^ http://www.el-carabobeno.com/nacional/articulo/31608/en-gaceta-decreto-de-quotley-secaquot-para-semana-santa

- ^ Australian Broadcasting Commission (2007) "Kava Ban 'Sparks Black Market Boom'", ABC Darwin 23 August 2007 http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2007/08/23/2012707.htm?site=darwin Accessed 18 October 2007

- ^ a b Greg Ryan, "Drink and the Historians: Sober Reflections on Alcohol in New Zealand 1840–1914," New Zealand Journal of History (April 2010) Vol.44, No.1

- ^ a b Richard Newman, "New Zealand's Vote For Prohibition In 1911," New Zealand Journal of History, April 1975, Vol. 9 Issue 1, pp 52-71

- ^ Massachusetts General Laws 138 33.

- ^ Prohibition--View Videos

References

- Susanna Barrows, Robin Room, and Jeffrey Verhey (eds.), The Social History of Alcohol: Drinking and Culture in Modern Society (Berkeley, Calif: Alcohol Research Group, 1987)

- Susanna Barrows and Robin Room (eds.), Drinking: Behavior and Belief in Modern History University of California Press, (1991)

- Jack S. Blocker, David M. Fahey, and Ian R. Tyrrell eds. Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History: An International Encyclopedia 2 Vol. (2003)

- JS Blocker, Jr. "Did prohibition really work? Alcohol prohibition as a public health innovation." Am J Public Health. 2006 Feb;96(2):233-43. Epub 2005 27 December.

- Ernest Cherrington, ed., Standard Encyclopaedia of the Alcohol Problem 6 volumes (1925–1930), comprehensive international coverage to late 1920s

- Jessie Forsyth Collected Writings of Jessie Forsyth 1847-1937: The Good Templars and Temperance Reform on Three Continents ed by David M. Fahey (1988)

- Gefou-Madianou. Alcohol, Gender and Culture (European Association of Social Anthropologists) (1992)

- Dwight B. Heath, ed; International Handbook on Alcohol and Culture Greenwood Press, (1995)

- Max Henius Modern liquor legislation and systems in Finland, Norway, Denmark and Sweden (1931)

- Max Henius The error in the National prohibition act (1931)

- Patricia Herlihy; The Alcoholic Empire: Vodka & Politics in Late Imperial Russia Oxford University Press, (2002)

- Daniel Okrent. Last Call; The Rise and Fall of Prohibition. New York: Scribner, 2010.

- Sulkunen, Irma. History of the Finnish Temperance Movement: Temperance As a Civic Religion (1991)

- Tyrrell, Ian; Woman's World/Woman's Empire: The Woman's Christian Temperance Union in International Perspective, 1880-1930 U of North Carolina Press, (1991)

- Mark Thornton, "Alcohol Prohibition was a Failure," Policy Analysis, Washington DC: Cato Institute, 1991.

- Mark Thornton, The Economics of Prohibition, Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press, 1991.

- White, Helene R. (ed.), Society, Culture and Drinking Patterns Reexamined (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers Center of Alcohol Studies, 1991).

- White, Stephen.Russia Goes Dry: Alcohol, State and Society (1995)

- Robert S. Walker and Samuel C. Patterson, OKLAHOMA GOES WET: THE REPEAL OF PROHIBITION (McGraw-Hill Book Co. Eagleton Institute Rutgers University 1960).

- Samuel C. Patterson and Robert S. Walker, "The Political Attitudes of Oklahoma Newspapers Editors: The Prohibition Issue," The Southwestern Social Science Quarterly (1961)

- Farness, Kate, "One Half So Precious", Dodd, Mead, and Company, (1995)