Probenecid

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Probalan |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682395 |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Protein binding | 75-95% |

| Elimination half-life | 2-6 hours (dose: 0.5-1 g) |

| Excretion | kidney (77-88%) |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.313 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

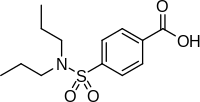

| Formula | C13H19NO4S |

| Molar mass | 285.36 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Probenecid, also sold under the brand name Probalan, is a medication that increases uric acid excretion in the urine. It is primarily used in treating gout and hyperuricemia.

Probenecid was developed as an alternative to caronamide[1] to competitively inhibit renal excretion of some drugs, thereby increasing their plasma concentration and prolonging their effects.

Medical uses

[edit]Probenecid is primarily used to treat gout and hyperuricemia.

Probenecid is sometimes used to increase the concentration of some antibiotics and to protect the kidneys when given with cidofovir. Specifically, a small amount of evidence supports the use of intravenous cefazolin once rather than three times a day when it is combined with probenecid.[2]

It has also found use as a masking agent,[3] potentially helping athletes using performance-enhancing substances to avoid detection by drug tests.

Adverse effects

[edit]Mild symptoms such as nausea, loss of appetite, dizziness, vomiting, headache, sore gums, or frequent urination are common with this medication. Life-threatening side effects such as thrombocytopenia, hemolytic anemia, leukemia and encephalopathy are extremely rare.[4] Theoretically probenecid can increase the risk of uric acid kidney stones.

Drug interactions

[edit]Some of the important clinical interactions of probenecid include those with captopril, indomethacin, ketoprofen, ketorolac, naproxen, cephalosporins, quinolones, penicillins, methotrexate, zidovudine, ganciclovir, lorazepam, and acyclovir. In all these interactions, the excretion of these drugs is reduced due to probenecid, which in turn can lead to increased concentrations of these.[5]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]In gout, probenecid competitively inhibits the reabsorption of uric acid through the organic anion transporter (OAT) at the proximal tubules. This leads to preferential reabsorption of probenecid back into plasma and excretion of uric acid in urine,[6] thus reducing blood uric acid levels and reducing its deposition in various tissues.

Probenecid also inhibits pannexin 1.[7] Pannexin 1 is involved in the activation of inflammasomes and subsequent release of interleukin-1β causing inflammation. Inhibition of pannexin 1 thus reduces inflammation, which is the core pathology of gout.[7]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]In the kidneys, probenecid is filtered at the glomerulus, secreted in the proximal tubule and reabsorbed in the distal tubule. Probenicid lowers the concentration of certain drugs in urine drug screens by reducing renal excretion of these drugs.

Historically, probenecid has been used to increase the duration of action of drugs such as penicillin and other beta-lactam antibiotics. Penicillins are excreted in the urine at proximal and distal convoluted tubules through the same organic anion transporter (OAT) as seen in gout. Probenecid competes with penicillin for excretion at the OAT, which in turn increases the plasma concentration of penicillin.[8]

History

[edit]During World War II, probenecid was used to extend limited supplies of penicillin. This use exploited probenecid's interference with drug elimination (via urinary excretion) in the kidneys and allowed lower doses of penicillin to be used.[9]

Probenecid was added to the International Olympic Committee's list of banned substances in January 1988, due to its use as a masking agent.[10]

References

[edit]- ^ Mason RM (June 1954). "Studies on the effect of probenecid (benemid) in gout". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 13 (2): 120–130. doi:10.1136/ard.13.2.120. PMC 1030399. PMID 13171805.

- ^ Cox VC, Zed PJ (March 2004). "Once-daily cefazolin and probenecid for skin and soft tissue infections". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 38 (3): 458–463. doi:10.1345/aph.1d251. PMID 14970368. S2CID 11449580.

- ^ Morra V, Davit P, Capra P, Vincenti M, Di Stilo A, Botrè F (December 2006). "Fast gas chromatographic/mass spectrometric determination of diuretics and masking agents in human urine: Development and validation of a productive screening protocol for antidoping analysis". Journal of Chromatography A. 1135 (2): 219–229. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2006.09.034. hdl:2318/40201. PMID 17027009. S2CID 20282106.

- ^ Kydd AS, Seth R, Buchbinder R, Edwards CJ, Bombardier C (November 2014). "Uricosuric medications for chronic gout". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (11): CD010457. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010457.pub2. PMC 11262558. PMID 25392987.

- ^ Cunningham RF, Israili ZH, Dayton PG (March–April 1981). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of probenecid". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 6 (2): 135–151. doi:10.2165/00003088-198106020-00004. PMID 7011657. S2CID 24497865.

- ^ "Probenecid". PubChem. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ^ a b Silverman W, Locovei S, Dahl G (September 2008). "Probenecid, a gout remedy, inhibits pannexin 1 channels". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 295 (3): C761–C767. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00227.2008. PMC 2544448. PMID 18596212.

- ^ Ho RH (January 2010). "4.25 - Uptake Transporters". In McQueen CA, Kim RB (eds.). Comprehensive Toxicology (Second ed.). Oxford: Elsevier. pp. 519–556. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-046884-6.00425-5. ISBN 978-0-08-046884-6.

- ^ Butler D (November 2005). "Wartime tactic doubles power of scarce bird-flu drug". Nature. 438 (7064): 6. Bibcode:2005Natur.438....6B. doi:10.1038/438006a. PMID 16267514.

- ^ Wilson W, Derse E, eds. (2001). Doping in Elite Sport: The Politics of Drugs in the Olympic Movement. Human Kinetics. p. 86. ISBN 0-7360-0329-0.