High school football

| High school football | |

|---|---|

An August 2015 high school football game in Commerce, Texas | |

| Country | United States Canada |

| Governing body | |

| National team(s) | |

| First played | 1870 |

National competitions | |

High school football national championships (United States) | |

High school football, also known as prep football, is gridiron football played by high school teams in the United States and Canada. It ranks among the most popular interscholastic sports in both countries. It is the level of tackle football that is played before college football.

Rules

[edit]The National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) establishes the rules of high school American football in the United States. In Canada, high school is governed by Football Canada and most schools use Canadian football rules adapted for the high school game except in British Columbia, which uses the NFHS rules.[1]

Since the 2019 high school season, Texas is the only state that does not base its football rules on NFHS rules, instead using NCAA rules with certain exceptions shown below.[2][3] Through the 2018 season, Massachusetts also based its rules on those of the NCAA,[4] but it adopted NFHS rules in 2019.[5]

With their common ancestry, NFHS rules of high school American football are largely similar to those of college football, though there are some important differences:

- The four quarters are each 12 minutes in length, as opposed to 15 minutes in college and professional football. Texas uses the NFHS 12-minute quarter.

- Kickoffs take place at the kicking team's 40-yard line, as opposed to the 35 in college and the NFL. (Texas has adopted the NFHS rule.)

- Hashmarks are 53 feet, 4 inches apart, dividing the field into thirds. College hashmarks have been 40 feet apart since 1993 (moved in from 53'4"), and National Football League (NFL) hashmarks have been 18 feet, 6 inches apart since 1972 (moved in from 40').

- If an attempted field goal is missed it is treated as a punt, normally it would be a touchback and the opposing team will start at the 20-yard line. However, if it does not enter the end zone, it can be downed or returned as a normal punt.

- The same rule was used in the NFL through 1973.

- The use of a kicking tee is legal for field goal and extra point attempts. Texas has adopted the NFHS rule, although tees have been banned by the NCAA since 1989.

- Any kick crossing the goal line is automatically a touchback; kicks cannot be returned out of the end zone.

- The spot of placement after all touchbacks—including those resulting from kickoffs and free kicks following a safety—is the 20-yard line of the team receiving possession. In contrast with NCAA rules, which call for the ball to be placed on the receiving team's 25-yard line if a kickoff or free kick after a safety results in a touchback, or NFL rules adopted in 2024, which places a touchback at the 20 or 30 depending upon whether or not the ball hit inside the "landing zone" prior to reaching the end zone.

- All fair catches result in the placement of the ball at the spot of the fair catch. Under NCAA rules, a kickoff or free kick after a safety that ends in a fair catch inside the receiving team's 25-yard line is treated as a touchback, with the ball spotted on the 25.

- Pass interference by the defense results in a 15-yard penalty, but no automatic first down (prior to 2013, the penalty also carried an automatic first down).

- Pass interference by the offense results in a 15-yard penalty, from the previous spot, and no loss of down.

- The defense cannot return an extra-point attempt for a score. Texas is the lone exception.

- Any defensive player that encroaches the neutral zone, regardless of whether the ball was snapped or not, commits a "dead ball" foul for encroachment. 5-yard penalty from the previous spot.

- Prior to 2013, offensive pass interference resulted in a 15-yard penalty and a loss of down. The loss of down provision was deleted from the rules starting in 2013. In college and the NFL, offensive pass interference is only 10 yards.

- The use of overtime, and the type of overtime used, is up to the individual state association. NFHS offers a suggested overtime procedure based on the Kansas Playoff, but does not make its provisions mandatory.

- The home team must wear dark-colored jerseys, and the visiting team must wear white jerseys. In the NFL, as well as conference games in the Southeastern Conference, the home team has choice of jersey color. Under general NCAA rules, the home team may wear white with approval of the visiting team, or both teams may wear colored jerseys if they sufficiently contrast.

- Since 2018, the so-called "pop-up kick"—a free kick technique sometimes used for onside kicks, in which the kicker drives the ball directly into the ground so that it bounces high in the air (thus eliminating the possibility of a fair catch)—has been banned.[6]

- Since 2019, NFHS gave its member associations the option to allow replay review in postseason games only.[7] Previously, it prohibited the use of replay review even if the venue had the facilities to support it. In Texas, the public-school sanctioning body, the University Interscholastic League, only allows replay review in state championship games, while the main body governing non-public schools, the Texas Association of Private and Parochial Schools, follows the pre-2019 NFHS practice of banning replay review.

- In 2022, the NFHS adopted an exception to the intentional grounding rule that allows a quarterback who is outside the tackle box to throw the ball away without penalty as long as the pass reaches the line of scrimmage, including its extension beyond the sidelines. The NFL and college football had long used this rule. It also made 0 a legal player number, although that digit remains banned as the first digit of a two-digit number.[8]

- In 2023, the base spot of enforcement for most offensive fouls behind the line of scrimmage changed from the spot of the foul to the previous line of scrimmage. Also, the intentional grounding rule adopted in 2022 was slightly modified; the only player who can benefit from the exception adopted in 2022 is the first player to possess the ball after the snap (almost always the quarterback).[9]

- In 2024, like the NFL, the UFL, and NCAA, Texas begin allowing the two-minute warning once the play ends and up to two minutes remain in the half.

At least one unique high school rule has been adopted by college football. In 1996, the overtime rules originally utilized by Kansas high school teams beginning in 1971 were adopted by the NCAA, although the NCAA has made five major modifications. Through the 2018 season, each possession started from the 25-yard line. Since 2021, this remains in force through the first two overtime procedures. In double overtime, teams must attempt a two-point conversion after a touchdown. Secondly, triple overtime & thereafter are two-point conversion attempts instead of possessions from the 25-yard line, and successful attempts are scored as conversions instead of touchdowns.

Thirty-four states have a mercy rule that comes into play during one-sided games after a prescribed scoring margin is surpassed at halftime or any point thereafter. The type of mercy rule varies from state to state, with many using a "continuous clock" after the scoring margin is reached. Except for specific situations, the clock keeps running on plays where the clock would normally stop. Other states end the game once the margin is reached or passed. Texas, for instance, uses a 45-point mercy rule to stop the game only in six-man football; for 11-man football, there is no automatic stoppage but the coaches may mutually agree to use a continuous clock.

Demographics

[edit]High school football in the United States is played almost entirely by boys. Over the past decade, girls have made up less than half a percent of the players of American high school football.[10] Eight states have high schools that sanction the non-contact alternative of flag football,[11] but none sanction tackle football for girls,[12] and a 2021 lawsuit in Utah that claimed the state violated Title IX laws by not sanctioning the sport was struck down.[13]

According to the New York Times, in 2006, 70% of high school football players were white and 20% were black. By 2018, those figures were 30% white and 40% black.[14] As of 2016[update], black youth are nearly three times more likely than white youth to play tackle football.[15]

In the 2010s, participation in high school football decreased in most states across the United States. Wisconsin saw the largest decrease, dropping by nearly a quarter from 2009 to 2019; only seven states saw an increased number of players.[16] Its popularity decline is partly due to risk of injury, particularly concussions.[17] According to The Washington Post, between 2009 and 2019, participation in high school football declined by 9.1%.[18]

Safety and brain health concerns

[edit]Robert Cantu, a Professor of Neurology and Neurosurgery and Co-Founder of the CTE Center at the Boston University School of Medicine, believes that children under 14 should not play tackle football.[19] Their brains are not fully developed, and myelin (nerve cell insulation) is at greater risk in shear when the brain is young. Myelination is completed at about 15 years of age. Children also have larger heads relative to their body size and weaker necks.[20][21]

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is caused by repeated brain trauma, such as concussions and blows to the head that do not produce concussions. It has been found in football players who had played for only a few years, including some who only played at the high school level.[22][23]

An NFL-funded study reported that high school football players suffered 11.2 concussions per 10,000 games or practices, nearly twice as many as college football players.[24]

According to 2017 study on brains of deceased gridiron football players, 99% of tested brains of NFL players, 88% of CFL players, 64% of semi-professional players, 91% of college football players, and 21% of high school football players had various stages of CTE.[25]

Other common injuries include injuries of legs, arms, and lower back.[26][27][28][29]

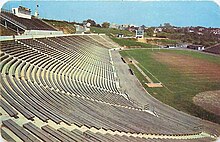

Largest high school stadiums by capacity

[edit]It has been suggested that this section be split into a new article titled List of high school football stadiums by capacity. (Discuss) (November 2023) |

The following is a list of the largest high school football stadiums in the United States, including stadiums with a capacity of at least 10,000.[30][31][32][33]

See also

[edit]- Eight-man football

- High School Football National Championship

- Nine-man football

- Six-man football

- USA Today All-USA high school football team

- USA Today High School Football Player of the Year

- Utah Girls Tackle Football League

References

[edit]- ^ "BCFOA Home". British Columbia Football Official's Association. Archived from the original on September 13, 2010. Retrieved September 1, 2010.

- ^ "2018–19 Football Manual" (PDF). University Interscholastic League. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ "Section 159 – Football Rules". TAPPS Constitution. Texas Association of Private and Parochial Schools. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ "Rule 69.1" (PDF). Rules and Regulations Governing Athletics. Massachusetts Interscholastic Athletic Association. July 1, 2009 – June 30, 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 16, 2009. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- ^ "MIAA Aligns Rules with NFHS in Football, Volleyball & Baseball" (Press release). National Federation of State High School Associations. August 8, 2018. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ^ "New Blocking, Kicking Rules Address Risk Minimization in High School Football" (Press release). National Federation of State High School Associations. April 24, 2018. Retrieved December 2, 2019.

- ^ "Football Rules Changes - 2019". National Federation of State High School Associations. May 16, 2019. Retrieved November 24, 2019.

- ^ "Revised Intentional Grounding, Chop Block Rules Headline 2022 High School Football Rules Changes" (Press release). National Federation of State High School Associations. February 17, 2022. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ "Changes in Basic Spot for Penalty Enforcement Headline 2023 High School Football Rules Changes" (Press release). National Federation of State High School Associations. February 2, 2023. Retrieved February 25, 2023.

- ^ "11-player football participation in U.S. high schools 2009-2022, by gender". Statista Research Department. September 2022. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ Lindkvist, Kierstin (2022-03-06). "All-girls flag football league wraps up winter season, looks to expand". KVAL. CBS. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ Bogage, Jacob (2019-05-02). "When Sam Gordon was 9, she beat boys at football. Now she wants a high school league for girls". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ "Judge Rules Utah Schools Don't Need To Sanction Girls' Football". KSLTV.com. 2021-03-03. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ Belson, Ken; Bui, Quoctrung; Drape, Joe; Taylor, Rumsey; Ward, Joe (2019-11-08). "Inside Football's Campaign to Save the Game". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ "RACE AND SPORT" (PDF). Women's Sports Foundation. July 2016. Retrieved 2022-12-01.

- ^ Hess, Corri (2023-10-12). "Wisconsin saw the nation's steepest decline in football participation. Now some schools are getting creative". Wisconsin Public Radio. Retrieved 2023-11-16.

- ^ "Concussions in High School Sports - Can Football be Saved? - Athletico". January 24, 2020.

- ^ Bogage, Jacob (3 October 2019). "D-III football players say choice to forfeit season after injuries was theirs, not college's". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2019-10-03.

Nationally, high school football participation has declined 9.1 percent over the past 10 years.

- ^ Nader, Ralph; Reed, Kenneth (November 8, 2016). "The X's and O's of brain injury and youth football". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on August 27, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ Cantu, " Concussions and Our Kids"

- ^ Paul Solotaroff, "This Is Your Brain on Football" Archived October 1, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, January 31, 2013, Rolling Stone

- ^ Toporek, Bryan (December 6, 2012). "New: High School Football Can Lead to Long-Term Brain Damage, Study Says". Education Week. Archived from the original on August 2, 2017. Retrieved August 26, 2017.

- ^ "Deadly Hits: The Story of Ex-football Player Chris Coyne". Lauren Tarshis YouTube page. Lauren Tarshis. September 21, 2012. Archived from the original on May 28, 2017. Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ Preps at greater concussion risk, ESPN, Tom Farrey, October 31, 2013.

- ^ Moran, Barbara (July 26, 2017). "BU Researchers Find CTE in 99% of Former NFL Players Studied". The Brink. Boston University.

- ^ Willigenburg, N. W.; Borchers, J. R.; Quincy, R.; Kaeding, C. C.; Hewett, T. E. (2016). "Comparison of Injuries in American Collegiate Football and Club Rugby: A Prospective Cohort Study - Nienke W. Willigenburg, James R. Borchers, Richard Quincy, Christopher C. Kaeding, Timothy E. Hewett, 2016". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 44 (3): 753–60. doi:10.1177/0363546515622389. PMID 26786902. S2CID 21829142.

- ^ Quinn, Elizabeth (November 27, 2019). "Common Aches, Pains, and Injuries You Can Expect From Playing Football". Verywell Fit.

- ^ Makovicka, J. L.; Patel, K. A.; Deckey, D. G.; Hassebrock, J. D.; Chung, A. S.; Tummala, S. V.; Hydrick, T. C.; Gulbrandsen, M.; Hartigan, D. E.; Chhabra, A. (2019). "Lower Back Injuries in National Collegiate Athletic Association Football Players: A 5-Season Epidemiological Study". Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine. 7 (6). doi:10.1177/2325967119852625. PMC 6582304. PMID 31245431.

- ^ "High School Sports News - live scores, stats, standings and projections". High School Sports News.

- ^ Adame, Tony (May 13, 2022). "Biggest High School Football Stadiums". Stadium Talk.[unreliable source?]

- ^ "Stadiums with Capacity Greater Than 16,500". TexasBob.com.[unreliable source?]

- ^ Shelton, Chris; Young, Matt (August 3, 2022). "Texas high school football: The 20 biggest, most expensive stadiums". Houston Chronicle.

- ^ Krider, Dave (July 25, 2014). "10 more High School Football Stadiums to See before you Die". Maxpreps.

- ESPN College Football Encyclopedia by Michael McCambridge – lists all-time records for all current Division I and Ivy League colleges, including games played against high school teams ISBN 1-4013-3703-1