Prajapati

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

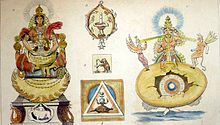

Prajapati (Sanskrit: प्रजापति, lit. 'Lord of the people', IAST: Prajāpati) is a Vedic deity of Hinduism and he is a form of Brahma, the creator god.[1][2][3]

Prajapati is a form of the creator-god Brahma, but the name is also the name of many different gods, in many Hindu scriptures, ranging from the creator god Brahma to being the same as one of the following deities: Vishvakarma, Agni, Indra, Daksha, and many others,[1] because of the diverse Hindu cosmology.[2] In classical and medieval era literature, Prajapati is the metaphysical concept called Brahman as Prajapati-Brahman, and Brahman is the primordial matter that made Prajapati.[4][5]

Etymology

[edit]Prajapati (Sanskrit: प्रजापति) is a compound of "praja" (creation, procreative powers) and "pati" (lord, master).[6] The term means "lord of creatures",[1][2] or "lord of all born beings".[7] In the later Vedic texts, Prajapati is a distinct Vedic deity, but whose significance diminishes.[2] Later, the term is synonymous with other gods, particularly Brahma.[1][3] Still later, the term evolves to mean any divine, semi-divine or human sages who create something new.[1][2][8]

Origins

[edit]

The origins of Prajapati are unclear. He appears late in the Vedic layer of texts, and the hymns that mention him provide different cosmological theories in different chapters.[3] He is missing from the Samhita layer of Vedic literature, conceived in the Brahmana layer, states Jan Gonda.[9] Prajapati is younger than Savitr, and the word was originally an epithet for the sun.[10] His profile gradually rises in the Vedas, peaking within the Brahmanas.[9] Scholars such as Renou, Keith and Bhattacharji posit Prajapati originated as an abstract or semi-abstract deity in the later Vedic milieu as speculations evolved from the archaic to more learned speculations.[10]

Similar Deities

[edit]A similarity between Prajapati (and related figures in Hindu mythology) and Phanes, also named as Protogonus (Ancient Greek: Πρωτογόνος, literally "first-born") of the Greco-Roman mythology has been proposed:[11][12]

Phanes is the Classical mythology equivalent of the Hindu god Brahma's Prajapati form in several ways: he is the first god born from a cosmic egg, he is the creator of the universe, and in the figure of Phanes— worshippers participate in his birth, death, rebirth, redeath.

— Kate Alsobrook, The Beginning of Time: Hindu Greco-Roman Theogonies and Poetics[12]

According to Robert Graves, the name of /PRA-JĀ[N]-pati/ ('progeny-potentate') is etymologically equivalent to that of the oracular god Phanes at Colophon (according to Macrobius[13]), namely /prōtogonos/.[14] The cosmic egg concept linked to Prajapati and Phanes is common in many parts of the world, states David Leeming, which appears in later Greco-Roman worship in Greece and Rome.[15]

Texts

[edit]Prajapati is described in many ways in Hindu texts, both in the Vedas and in the post-Vedic texts. These range from Brahma to being same as one of the following: Agni, Indra, Vishvakarma, Daksha and many others.[1][16]

Vedas

[edit]His role varies within the Vedic texts such as being one who created heaven and earth, all of waters and beings, the creator of the universe, the creator of gods and goddesses, the creator of devas and devis and asuras and asuris and the cosmic egg and the Purusha.[2][7] His role peaked in the Brahmanas layer of Vedic texts, then declined to name a group of creators in the creation process.[2] In some Brahmana texts, his role is paired since he co-creates with the powers of the creator goddess Vac.[17]

In the Rigveda, Prajapati appears as a name for Savitr, Chandra, Agni and Indra, who are all praised as equal, same and gods of creatures.[18] Elsewhere, in hymn 10.121 of the Rigveda, is described Hiranyagarbha (golden embryo) that was born from the waters containing everything, which produced Prajapati. It then created manas (mind), kama (desire), tapas (heat) and Prajapati created the universe. And this Prajapati is a creator god who created the universe, one of many Hindu cosmology theories, and there is no supreme god or supreme goddess in the Rigveda.[19][20][21] One of the striking features about the Hindu Prajapati myths, states Jan Gonda, is the idea that the work of creation is a gradual process, completed in stages of trial and improvement.[22]

In the Shatapatha Brahmana, embedded inside the Yajurveda, Prajapati was self-created from Brahman (Ultimate Reality) and Prajapati co-creates the world with Vac.[23] It also includes the "golden cosmic egg" mythology, wherein Prajapati is stated to be born from a golden egg in primeval sea after the egg was incubated for a year. His sounds became the sky, the earth and the seasons. When he inhaled, he created the devas and devis, and light. When he exhaled, he created the asuras and asuris, and darkness. Then, together with the Vac, he and she created all beings and universe.[24] In Chapter 10 of the Shatapatha Brahmana, as well as chapter 13 of Pancavimsa Brahmana, is presented another myth where in Prajapati is a creator god, becomes creating with Vac, the creator goddess, all living creatures generated, then Mrtyu seizes these beings within his and her womb, but because these beings are created by Prajapati and Vac, they desire to live like him and her and Prajapati and Vac kill Mrtyu and creates the universe with releasing all living creatures in his and her womb.[25][26]

The Aitareya Brahmana tells a different myth, wherein Prajapati, having created the gods and goddesses, turns into a stag and approaches his daughter with Vac, Ushas who was in the form of a doe, to produce other animals. The gods and goddesses are horrified by this incest, and joined forces and created the angry destructive Rudra to kill Prajapati for doing incest with Ushas and before Prajapati mates with Ushas, Rudra drives Prajapati away. Then Rudra kills Prajapati and Ushas runs away and Prajapati is resurrected.[24] The Sankhyayana Brahmana tells another myth, wherein Prajapati created Agni, Surya, Chandra, Vayu, Ushas and all deities. Agni, Surya, Chandra, Vayu, Ushas and all deities released their energies and created the universe.[24]

In section 2.266 of Jaiminiya Brahmana, Prajapati is presented as a spiritual teacher. His student Varuna lives with him for 100 years, studying the art and duties of being the "father-like king of gods and goddesses" and is a king of the gods and goddesses.[27][28]

Upanishads

[edit]Prajapati appears in early Upanishads, among the most influential texts in Hinduism.[29] He is described in the Upanishads in diverse ways. For example, in different Upanishads, he is presented as the personification of creative power after Brahman,[30] the same as the wandering eternal soul,[31] as symbolism for unmanifest obscure first born,[32] as manifest procreative sexual powers,[33] the knower particularly of Atman (soul, self),[34] and a spiritual teacher that is within each person.[35][36] The Chandogya Upanishad, as an illustration, presents him as follows:[37]

The self (atman) that is free from evils, free from old age and death, free from sorrow, free from hunger and thirst; the self whose desires and intentions are real – that is the self that you should try to discover, that is the self that you should seek to perceive. When someone discovers that self and perceives it, he obtains all the worlds, and all his desires are fulfilled, so said Prajapati.

In Chandogya Upanishad 1.2.1, Prajapati appears as the creator of all devas and devis and asuras and asuris: "The gods and goddesses and the demons and demonesses are both children of Prajapati, yet they fought among themselves." (Sanskrit: देवासुरा ह वै यत्र संयेतिरे उभये प्राजापत्यास्तद्ध, romanized: devāsurā ha vai yatra saṃyetire ubhaye prājāpatyāstaddha).[38]

Post-Vedic texts

[edit]In the Mahabharata, Brahma is declared to be a Prajapati who creates many males and females, and imbues them with desire and anger, the former to drive them into reproducing themselves and the latter to be being like gods and goddesses.[24] Other chapters of the epics and Puranas declare Vishnu and Shiva to be Prajapatis.[18]

The Bhagavad Gita uses the epithet Prajapati to describe Krishna, the eight incarnation of Vishnu in the Dashavatara of Vishnu along with many other epithets.[39]

The Grhyasutras include Prajapati as among the deities invoked during wedding ceremonies and prayed to for blessings of prosperous progeny, and harmony between husband and wife.[40]

Prajapati is the God of Universe, Fire, Sun, Creation, etc. He is also identified with various mythical progenitors, especially (Manusmriti 1.34) the ten gods of created beings which are first created by Brahma: Marichi, Atri, Angiras, Pulastya, Pulaha, Kratu, Vasishtha, Daksha, Bhrigu, Narada.[41]

In the Puranas, there are groups of Prajapatis called Prajapatayah who were rishis (sages) from whom all of the world is created, followed by a Prajapatis list that widely varies in number and name between different texts.[1][2] According to George Williams, the inconsistent, varying and evolving Prajapati concept in Hindu mythology reflects the diverse Hindu cosmology.[2]

The Mahabharata and the genre of Puranas call various gods and sages as Prajapati. Some illustrations, states Roshen Dalal, include Agni, Bharata, Shashabindu, Shukra, Havirdhaman, Indra, Kapila, Kshupa, Prithu, Chandra, Svishtakrita, Tvashtra, Vishvakarma, Virana.[1]

In the medieval era texts of Hinduism, Prajapatis refers to legendary agents of creation, gods and sages who are working in creation, who appear in every cycle of creation-maintenance-destruction. Their numbers vary between seven, ten, sixteen or twenty-one at times.[1]

"Prajapati" as a title

[edit]Prajapati is also a title in Hindu cosmology. According to the Shanti Parva of the Mahabharata, Brahma initially created twenty-one Prajapatis to facilitate the process of creation. [42]

A list of sixteen found in the Mahabharata includes

[edit]- Shiva

- Vaivasvata Manu

- Daksha

- Bhrigu

- Dharma

- Tapa

- Yama

- Marici

- Angiras

- Atri

- Pulastya

- Pulaha

- Kratu

- Vasishtha

- Parameshti

- Surya

- Chandra

- Kardama

- Krodha

- Vikrita

- Brahma.[1][2]

A list of sixteen found in the Ramayana includes

[edit]- Angiras

- Arishtanemi

- Atri

- Daksha

- Kardama

- Kashyapa

- Kratu

- Marichi

- Prachetas

- Pulaha

- Pulastya

- Samshraya

- Shesha

- Vasishtha

- Chandra

- Surya.[1]

A list of ten in the Hindu scriptures includes

[edit]A list of seven in the Hindu Puranas includes

[edit]Their creative role varies. Pulaha, for example, is the son of Brahma and Sarasvati and he is a great rishi. As one of the Prajapatis, he creates animals and plants.[43]

Balinese Hinduism

[edit]Hindu temples in Bali, Indonesia that are dedicated to Brahma as Prajapati are called as Pura Prajapati, also called as Pura Mrajapati, are common. They are mostly associated with funeral rituals and the Ngaben (cremation) ceremony for the dead where Brahma as Prajapati is invoked to preside over the funeral ceremonies happening there.[44][45]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. pp. 234–235. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2.

- ^ a b c James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 518–519. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- ^ Sukumari Bhattacharji (2007). The Indian Theogony. Cambridge University Press. pp. 322–323, 337, 338, 341–342.

- ^ "Prajapati, Prajāpati, Prajāpatī, Praja-pati: 30 definitions". 28 September 2010.

- ^ Jan Gonda (1982), The Popular Prajāpati Archived 15 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, History of Religions, Vol. 22, No. 2 (Nov., 1982), University of Chicago Press, pp. 137-141

- ^ a b Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- ^ James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 169, 518–519. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- ^ a b Jan Gonda (1986). Prajāpatiʼs rise to higher rank. BRILL Academic. pp. 2–5. ISBN 90-04-07734-0.

- ^ a b Jan Gonda (1982), The Popular Prajāpati Archived 15 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, History of Religions, Vol. 22, No. 2 (Nov., 1982), University of Chicago Press, pp. 129-130

- ^ Martin West, Early Greek Philosophy and the Orient. Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1971: 28-34

- ^ a b Kate Alsobrook (2008), "The Beginning of Time: Vedic and Orphic Theogonies and Poetics". M.A. Thesis, Reviewers: James Sickinger, Kathleen Erndl, John Marincola and Svetla Slaveva-Griffin, Florida State University, pages 20, 1-5, 24-25, 40-44

- ^ Robert Graves : The Greek Myths. 1955. vol. 1, p. 31, sec. 2.2

- ^ "Protogonos Greek First Born From Prajapati Hinduism". Ramanisblog. 12 August 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2024.

- ^ David Adams Leeming (2010). Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 313–314. ISBN 978-1-59884-174-9.

- ^ Sukumari Bhattacharji (2007). The Indian Theogony. Cambridge University Press. pp. 322–330.

- ^ David Kinsley (1988). Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. University of California Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-520-90883-3.

- ^ a b Sukumari Bhattacharji (2007). The Indian Theogony. Cambridge University Press. pp. 322–323.

- ^ Gavin D. Flood (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

- ^ Henry White Wallis (1887). The Cosmology of the Ṛigveda: An Essay. Williams and Norgate. pp. 61–73, 117.

- ^ Laurie L. Patton (2005). Bringing the Gods to Mind: Mantra and Ritual in Early Indian Sacrifice. University of California Press. pp. 113, 216. ISBN 978-0-520-93088-9.

- ^ Jan Gonda (1986). Prajāpatiʼs rise to higher rank. BRILL Academic. pp. 20–21. ISBN 90-04-07734-0.

- ^ Annette Wilke; Oliver Moebus (2011). Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 414–416. ISBN 978-3-11-024003-0.

- ^ a b c d David Adams Leeming (2010). Creation Myths of the World: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 144–146. ISBN 978-1-59884-174-9.

- ^ Jan Gonda (1986). Prajāpatiʼs rise to higher rank. BRILL Academic. pp. 5, 14–16. ISBN 90-04-07734-0.

- ^ Sukumari Bhattacharji (2007). The Indian Theogony. Cambridge University Press. pp. 324–325.

- ^ Jan Gonda (1986). Prajāpatiʼs rise to higher rank. BRILL Academic. pp. 17–18. ISBN 90-04-07734-0.

- ^ Sukumari Bhattacharji (2007). The Indian Theogony. Cambridge University Press. pp. 326–327.

- ^ Patrick Olivelle (2014), The Early Upanisads, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195352429, pages 3, 279-281; Quote: "Even though theoretically the whole of vedic corpus is accepted as revealed truth [shruti], in reality it is the Upanishads that have continued to influence the life and thought of the various religious traditions that we have come to call Hindu. Upanishads are the scriptures par excellence of Hinduism".

- ^ Paul Deussen (1980). Sixty Upaniṣads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 19–21, 205, 240, 350, 510, 544. ISBN 978-81-208-1468-4.

- ^ Paul Deussen (1980). Sixty Upaniṣads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 495. ISBN 978-81-208-1468-4.

- ^ Paul Deussen (1980). Sixty Upaniṣads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 85, 96–97, 252. ISBN 978-81-208-1468-4.

- ^ Paul Deussen (1980). Sixty Upaniṣads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 53–56, 471, 534, 540. ISBN 978-81-208-1468-4.

- ^ Paul Deussen (1980). Sixty Upaniṣads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 371. ISBN 978-81-208-1468-4.

- ^ Paul Deussen (1980). Sixty Upaniṣads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 21, 106, 198–205, 263, 508, 544. ISBN 978-81-208-1468-4.

- ^ Klaus G. Witz (1998). The Supreme Wisdom of the Upaniṣads: An Introduction. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 115, 145–153, 363–365. ISBN 978-81-208-1573-5.

- ^ a b The Early Upanishads: Annotated Text and Translation. Oxford University Press. 1998. pp. 279–281. ISBN 978-0-19-535242-9.

- ^ www.wisdomlib.org (4 January 2019). "Chandogya Upanishad, Verse 1.2.1 (English and Sanskrit)". www.wisdomlib.org. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ Winthrop Sargeant (2010). Christopher Key Chapple (ed.). The Bhagavad Gita: Twenty-fifth–Anniversary Edition. State University of New York Press. pp. 37, 167, 491 (verse 11.39). ISBN 978-1-4384-2840-6.

- ^ Jan Gonda (1982), The Popular Prajāpati Archived 15 February 2020 at the Wayback Machine, History of Religions, Vol. 22, No. 2 (Nov., 1982), University of Chicago Press, pp. 131-132

- ^ Wilkins, W.J. (2003). Hindu Mythology. New Delhi: D.K. Printworld (P) Limited. p. 369. ISBN 81-246-0234-4.

- ^ Mani, Vettam (1975). Puranic Encyclopaedia: A Comprehensive Dictionary with Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 0842608222. Retrieved from Internet Archive on [access date].

- ^ Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin. p. 316. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- ^ David J. Stuart-Fox (2002). Pura Besakih: Temple, Religion and Society in Bali. KITLV. pp. 92–94, 207–209. ISBN 978-90-6718-146-4.

- ^ Between Harmony and Discrimination: Negotiating Religious Identities within Majority-Minority Relationships in Bali and Lombok. BRILL. 2014. pp. 264–266. ISBN 978-90-04-27149-4.

Further reading

[edit]- Dictionary of Hindu Lore and Legend (ISBN 0-500-51088-1) by Anna Dhallapiccola

External links

[edit]- Prajapati: Hindu Deity, Encyclopaedia Britannica