Björneborgarnas marsch

| English: March of the Björneborgers or March of the Pori Regiment | |

|---|---|

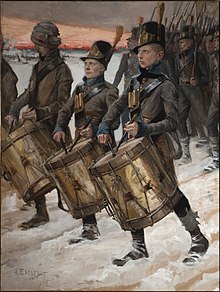

Swedish soldiers of the Royal Björneborg regiment during the Finnish war (1808–1809). Painting by Albert Edelfelt, 1892. | |

Military anthem of Song of the Military anthem of the Song of the Song of the Commander-in-Chief of the Estonian Defence Forces | |

| Lyrics | Johan Ludvig Runeberg (Swedish), 1860 Paavo Cajander (Finnish), 1889 |

| Music | Unknown, 18th century |

| Adopted | 1918 |

| Audio sample | |

Björneborgarnas marsch (Finnish: Porilaisten marssi; Estonian: Porilaste marss; 'March of the Björneborgers' or 'March of the Pori Regiment') is a Swedish military march from the 18th century. Today, it is mainly performed in Finland and Estonia and has served as the honorary march of the Finnish Defence Forces since 1918 and is the Estonian Defence Forces' official honorary march.[1]

History

[edit]The original melody of Björneborgarnas marsch is most likely French in origin, and was composed by an unknown composer in the 18th century, although the modern brass band arrangement is by the Finnish German composer Konrad Greve.[2][3][4][5]

Later in the same century, it was made popular in Sweden by the poet Carl Michael Bellman, who used it as a basis for his epistle 51 "Movitz blåste en konsert" (Movitz blew a concert), and was subsequently adopted as a military march by the Royal Swedish army. Following Sweden's defeat to Russia in the Finnish War of 1808–1809, her eastern lands formed the Russian-controlled Grand Duchy of Finland.[6]

The march remained popular throughout the 19th century in both Sweden and Finland. The original text was published in Swedish in 1860 by the Finnish national poet Johan Ludvig Runeberg in his epic poem The Tales of Ensign Stål, although Zachris Topelius had also given it his own words in 1858.[2][3] The most commonly used Finnish translation was written by Paavo Cajander in 1889, along with Cajander's translation of The Tales of Ensign Stål.[3] The name of the march refers to the Björneborg regiment (Pori in Finnish) of the Swedish army. It contains an iambic meter.

Use

[edit]Björneborgarnas marsch today serves as the honorary march of the Finnish Defence Forces and is played (only rarely sung) for the Commander-in-Chief, i.e. the President of Finland.[3] The President has, however, the right to delegate this position to another Finnish citizen; the only time this has occurred was during the World War II, when Marshal Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim acted as Commander-in-Chief instead of then-President Risto Ryti. Thus, Ryti is the only President of Finland not to have been Commander-in-Chief at any point of his two terms (1940–1944).

As Finland and Estonia share similarities in their languages, culture and also through their respective military traditions, it is also the Estonian Defence Forces' official honorary march, played for the Commander of the Estonian Defence Forces, its Commander-in-Chief appointed, under constitutional provisions, to the office by the Ministry of Defence and the Cabinet on the proposal of the President of the Republic of Estonia. The tune was first publicly played in Estonia at the 7th Estonian Song Festival in 1910.[7] It was also the march of the State Elder (later as presidential march) in Estonia till 27 January 1923 when the then-Minister of War Jaan Soots replaced it with the Pidulik marss which had won the contest for Estonian-composed state honorary march in 1922.[8][9][10]

Non-political

[edit]Since 1948, the Finnish national broadcast company Yleisradio has played Björneborgarnas marsch played on radio or television every time a Finnish athlete wins a gold medal in the Olympic games – the traditional phrase to initiate this was "Pasila, Porilaisten Marssi" (radio) and "Helsinki, Porilaisten Marssi" (television). An exception to this was made in 1998 when MTV3 similarly asked the song to be played after Mika Häkkinen won the 1998 Formula One World Championship.[11]

Björneborgarnas marsch is also played on Christmas Eve during the Declaration of Christmas Peace ceremony, which has caused minor controversy due to the violent lyrics of the march, even though the lyrics are not sung on the occasion.

In the video game My Summer Car, the march is played on the intro, where the protagonist is born in the back seat of their parents' (and later, said protagonist's) car, as they rush to a hospital. A remixed version can be heard in the credits scene.

Lyrics

[edit]Original Swedish lyrics

[edit]Johan Ludvig Runeberg, 1860

- Söner av ett folk, som blött

- På Narvas hed, på Polens sand, på Leipzigs slätter, Lützens kullar,

- Än har Finlands kraft ej dött,

- Än kan med oväns blod ett fält här färgas rött!

- Bort, bort, vila, rast och fred!

- En storm är lös, det ljungar eld och fältkanonens åska rullar;

- Framåt, framåt led vid led!

- På tappre män se tappre fäders andar ned.

//

- Ädlaste mål

- Oss lyser på vår bana;

- Skarpt är vårt stål

- Och blöda är vår vana.

- Alla, alla käckt framåt!

- Här är vår sekelgamla frihets sköna stråt.

//

- Lys högt, du segersälla fana,

- Sliten av strider sen en grånad forntids dar,

- Fram, fram, vårt ädla, härjade standar!

- Än finns en flik med Finlands gamla färger kvar.

//

Lyrics in Finnish

[edit]Translation by Paavo Cajander, 1889.

- Pojat, kansan urhokkaan,

- mi Puolan, Lützenin ja Narvan

- tanterilla verta vuoti,

- viel' on Suomi voimissaan,

- voi vihollisen hurmehella peittää maan!

- Pois, pois, toimet rauhaisat!

- Jo tulta tuiskii, myrsky käy,

- jo viuhkaa kanuunasta luoti.

- Eespäin, miehet uljahat!

- Meit' urhoollisten isäin henget seuraavat.

- Kas kunnian jo tähti meille hohtaa!

- Tuttavahan on verityö, mi kohtaa.

- Eespäin kaikki rientäkää!

- Vapautemme ikivanha tie on tää.

- Voittoisa lippu meitä johtaa,

- muinahisaikain taisteluista ryysyinen.

- Eespäin, sä jalo vaate verinen!

- Viel' liehuu jäännös Suomen värein entisten.

Lyrics in Estonian

[edit]- Üles, vaimud vahvamad

- kes Pärnu piirilt Peipsini

- kes terves Eestis elamas

- sest veel on Eestis vaimustust

- mis kaitsma valmis kodupinna vabadust

- Ja kuni särab meile tähte hele läik

- meeles kõigil Riia võidukäik

- Sest vahvad vaimud ärgake

- Taas Eesti lippu lehvitage võidule

- Välgu nüüd mõõk!

- Värise vaenlane!

- Paukuge püssid, vastu rõhujatele

- surma ei karda eesti maleva!

- Ei iial Eestit orjastada lase ta!

- Pojad rahva vahvama

- kes Pihkva, Jamburi ja Võnnu

- väljadele külvand surma

- Veel võib Eesti võidelda

- veel vaenulise verega võib värvi maa

- Kuulsuse täht toob hiilgust meie teile

- Kõik koos tulle tormake

- Me vabaduse kindlustuse tee on see

- Välgu nüüd mõõk...

Lyrics in English

[edit]Modern translation.

- Sons of a people whose blood was shed,

- On the field of Narva; Polish sand; at Leipzig; on Lützen's dark hills;

- Not yet is Finland defeated;

- With the blood of foes a field may still be tinted red!

- Rest, begone, away with peace!

- A storm unleashed; lightning swarms and cannons thunder on,

- Forward! Forward, line by line!

- Brave fathers look down on brave sons.

- No nobler aim,

- Could light our way,

- Our steel is sharp,

- To bleed is our custom,

- Man by man, brave and bold!

- Behold our ancient freedom's march!

- Shine bright, our victorious banner!

- Torn by distant battles of days gone,

- Be proud, our noble, tattered Standard!

- There is still a piece of Finland's ancient Colours left!

Arrangements

[edit]- military band, arranged in 1851 by the German-Finnish composer and bandleader Konrad Greve

- male choir a cappella, arranged in 1858 by the German-Finnish composer Fredrik Pacius to words by Zacharias Topelius, replaced in 1860 with words by Johan Ludvig Runeberg (Recording: Henrik Wikström and Akademiska Sångföreningen for BIS Records, CD–1694)

- mixed choir a cappella, arranged in ???? by the Finnish composer Martin Wegelius to words by ????

- chamber ensemble, arranged in 1892 by the Finnish composer Jean Sibelius (lost)

- orchestra, arranged in 1900 by Sibelius (Recording: Osmo Vänskä and the Lahti Symphony Orchestra for BIS Records, CD–1445)

- piano, arranged c. 1901 by the Finnish composer Selim Palmgren (Recording: Jouni Somero for Grand Piano, GP939)

- orchestra, arranged in 1904 by the Finnish composer Robert Kajanus (Recording: Osmo Vänskä and the Lahti Symphony Orchestra for BIS Records, CD–575)

- piano, arranged in ???? by the Finnish composer Armas Järnefelt (Recording: Janne Oksanen for Alba Records, ABCD 506)

See also

[edit]- "Maamme", Finnish national anthem

- "Mu isamaa, mu õnn ja rõõm", Estonian national anthem

- "Naprej, zastava slave", the Slovene military and presidential anthem

References

[edit]- ^ "Mitenkä Porilaisten marssi on syntynyt?". Kysy (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ a b "Porilaisten Marssi". Presidentti (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 10 June 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d Latvakangas, Eva (5 February 2006). "Musikaalihitistä kunniamarssiksi". Turun Sanomat (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 17 September 2022. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Jussila, Risto (1 September 2009). "Porilaisten marssi ei olekaan porilainen". Keskisuomalainen (in Finnish). Archived from the original on 29 July 2021. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Sirén, Vesa (6 December 2013). "Onko se Porilaisten marssi?". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- ^ Lagus, Ernst (1904). "Björneborgarnes marsch: Efter »en musik- och kulturhistorisk essay»". Svensk Musiktidning (in Swedish): 27–29.

- ^ "VII LAULUPIDU (1910)" (in Ewe). Eesti Laulu- ja Tantsupeo SA. Archived from the original on 17 May 2021. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- ^ Eesti Rahvusringhääling (16 February 2021). "Eero Raun: "Piduliku marsi" autorit süüdistati esialgu plagiaadis". menu.err.ee (in Estonian). Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ Sõjaministeerium (1921), "Sõjaministri päevakäsud (1 Jan – 31 Dec 1921, nr. 1-753)", www.digar.ee (in Ewe), archived from the original on 17 September 2022, retrieved 23 April 2022

- ^ Sõjaministeerium (1923), "Sõjaministri päevakäsud (3 Jan – 31 Dec 1923, nr. 4-584)", www.digar.ee (in Ewe), archived from the original on 23 April 2022, retrieved 23 April 2022

- ^ Rautio, Samppa (24 February 2018). ""Pasila, Porilaisten marssi" – Miksi suomalaisen voittaessa olympiakultaa Yle soittaa Porilaisten marssin eikä vaikka Sandstormia? Yle Urheilun päällikkö avaa tradition taustat". Iltalehti. Alma Media. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

External links

[edit]- Porilaisten marssi in YouTube

- Recording of the song (WAV format) at the official website of the President of Finland