Separator (electricity)

A separator is a permeable membrane placed between a battery's anode and cathode. The main function of a separator is to keep the two electrodes apart to prevent electrical short circuits while also allowing the transport of ionic charge carriers that are needed to close the circuit during the passage of current in an electrochemical cell.[1]

Separators are critical components in liquid electrolyte batteries. A separator generally consists of a polymeric membrane forming a microporous layer. It must be chemically and electrochemically stable with regard to the electrolyte and electrode materials and mechanically strong enough to withstand the high tension during battery construction. They are important to batteries because their structure and properties considerably affect the battery performance, including the batteries energy and power densities, cycle life, and safety.[2]

History

[edit]This article appears to be slanted towards recent events. In particular, Should cover separators used in older battery technologies, not just modern Li-ion separators. (June 2022) |

Unlike many forms of technology, polymer separators were not developed specifically for batteries. They were instead spin-offs of existing technologies, which is why most are not optimized for the systems they are used in. Even though this may seem unfavorable, most polymer separators can be mass-produced at a low cost, because they are based on existing forms of technologies.[3] Yoshino and co-workers at Asahi Kasei first developed them for a prototype of secondary lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) in 1983.

Initially, lithium cobalt oxide was used as the cathode and polyacetylene as the anode. Later in 1985, it was found that using lithium cobalt oxide as the cathode and graphite as the anode produced an excellent secondary battery with enhanced stability, employing the frontier electron theory of Kenichi Fukui.[4] This enabled the development of portable devices, such as cell phones and laptops. However, before lithium ion batteries could be mass-produced, safety concerns needed to be addressed such as overheating and over potential. One key to ensuring safety was the separator between the cathode and anode. Yoshino developed a microporous polyethylene membrane separator with a “fuse” function.[5] In the case of abnormal heat generation within the battery cell, the separator provides a shutdown mechanism. The micropores close by melting and the ionic flow terminates. In 2004, a novel electroactive polymer separator with the function of overcharge protection was first proposed by Denton and coauthors.[6] This kind of separator reversibly switches between insulating and conducting states. Changes in charge potential drive the switch. More recently, separators primarily provide charge transport and electrode separation.

Materials

[edit]Materials include nonwoven fibers (cotton, nylon, polyesters, glass), polymer films (polyethylene, polypropylene, poly (tetrafluoroethylene), polyvinyl chloride), ceramic[7] and naturally occurring substances (rubber, asbestos, wood). Some separators employ polymeric materials with pores of less than 20 Å, generally too small for batteries. Both dry and wet processes are used for fabrication.[8][9]

Nonwovens consist of a manufactured sheet, web or mat of directionally or randomly oriented fibers.

Supported liquid membranes consist of a solid and liquid phase contained within a microporous separator.

Some polymer electrolytes form complexes with alkali metal salts, which produce ionic conductors that serve as solid electrolytes.

Solid ion conductors, can serve as both separator and the electrolyte.[10]

Separators can use a single or multiple layers/sheets of material.

Production

[edit]Polymer separators generally are made from microporous polymer membranes. Such membranes are typically fabricated from a variety of inorganic, organic and naturally occurring materials. Pore sizes are typically larger than 50-100 Å.

Dry and wet processes are the most common separation production methods for polymeric membranes. The extrusion and stretching portions of these processes induce porosity and can serve as a means of mechanical strengthening.[11]

Membranes synthesized by dry processes are more suitable for higher power density, given their open and uniform pore structure, while those made by wet processes are offer more charge/discharge cycles because of their tortuous and interconnected pore structure. This helps to suppress the conversion of charge carriers into crystals on anodes during fast or low temperature charging.[12]

Dry process

[edit]The dry process involves extruding, annealing and stretching steps. The final porosity depends on the morphology of the precursor film and the specifics of each step. The extruding step is generally carried out at a temperature higher than the melting point of the polymer resin. This is because the resins are melted to shape them into a uniaxially-oriented tubular film, called a precursor film. The structure and orientation of the precursor film depends on the processing conditions and the resin's characteristics. In the annealing process, the precursor is annealed at a temperature slightly lower than the polymer's melting point. The purpose of this step is to improve the crystalline structure. During stretching, the annealed film is deformed along the machine direction by a cold stretch followed by a hot stretch followed by relaxation. The cold stretch creates the pore structure by stretching the film at a lower temperature with a faster strain rate. The hot stretch increases pore sizes using a higher temperature and a slower strain rate. The relaxation step reduces internal stress within the film.[13][14]

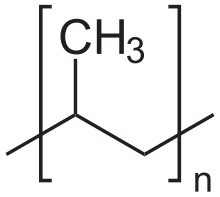

The dry process is only suitable for polymers with high crystallinity. These include but are not limited to: semi-crystalline polyolefins, polyoxymethylene, and isotactic poly (4-methyl-1-pentene). One can also use blends of immiscible polymers, in which at least one polymer has a crystalline structure, such as polyethylene-polypropylene, polystyrene-polypropylene, and poly (ethylene terephthalate) - polypropylene blends.[9][15]

Dry Microstructure

[edit]After processing, separators formed from the dry process possess a porous microstructure. While specific processing parameters (such as temperature and rolling speed) influence the final microstructure, generally, these separators have elongated, slit-like pores and thin fibrils that run parallel to the machine direction. These fibrils connect larger regions of semi-crystalline polymer, which run perpendicular to the machine direction.[11]

Wet process

[edit]The wet process consists of mixing, heating, extruding, stretching and additive removal steps. The polymer resins are first mixed with, paraffin oil, antioxidant and other additives. The mixture is heated to produce a homogenous solution. The heated solution is pushed through a sheet die to make a gel-like film. The additives are then removed with a volatile solvent to form the microporous result.[16] This microporous result can then be stretched uniaxially (along the machine direction) or biaxially (along both the machine and transverse directions, providing further pore definition.[11]

The wet process is suitable for both crystalline and amorphous polymers. Wet process separators often use ultrahigh-molecular-weight polyethylene. The use of these polymers enables the batteries with favorable mechanical properties, while shutting it down when it becomes too hot.[17]

Wet Microstructure

[edit]When subjected to biaxial stretching, separators formed from the wet process have rounded pores. These pores are dispersed throughout an interconnected polymer matrix.[11]

Choice of polymer

[edit]

Specific types of polymers are ideal for the different types of synthesis. Most polymers currently used in battery separators are polyolefin based materials with semi-crystalline structure. Among them, polyethylene, polypropylene, PVC, and their blends such as polyethylene-polypropylene are widely used. Recently, graft polymers have been studied in an attempt to improve battery performance, including micro-porous poly(methyl methacrylate)-grafted[16] and siloxane grafted polyethylene separators, which show favorable surface morphology and electrochemical properties compared to conventional polyethylene separators. In addition, polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) nanofiber webs can be synthesized as a separator to improve both ion conductivity and dimensional stability.[3] Another type of polymer separator, polytriphenylamine (PTPAn)-modified separator, is an electroactive separator with reversible overcharge protection.[6]

Placement

[edit]

The separator is always placed between the anode and the cathode. The pores of the separator are filled with the electrolyte and packaged for use.[18]

Essential properties

[edit]- Chemical stability

- The separator material must be chemically stable against the electrolyte and electrode materials under the strongly reactive environments when the battery is fully charged. The separator should not degrade. Stability is assessed by use testing.[17]

- Thickness

- A battery separator must be thin to facilitate the battery's energy and power densities. A separator that is too thin can compromise mechanical strength and safety. Thickness should be uniform to support many charging cycles. 25.4 μm (1.0 mil) is generally the standard width. The thickness of a polymer separator can be measured using the T411 om-83 method developed under the auspices of the Technical Association of the Pulp and Paper Industry.[19]

- Porosity

- The separator must have sufficient pore density to hold liquid electrolyte that enables ions to move between the electrodes. Excessive porosity hinders the ability of the pores to close, which is vital to allow the separator to shut down an overheated battery. Porosity can be measured using liquid or gas absorption methods according to the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) D-2873. Typically, a Li-ion battery separator provides porosity of 40%.[12]

- Pore size

- Pore size must be smaller than the particle size of the electrode components, including the active materials and conducting additives. Ideally the pores should be uniformly distributed while also having a tortuous structure. This ensures a uniform current distribution throughout the separator while suppressing the growth of Li on the anode. The distribution and structure of pores can be analyzed using a Capillary Flow Porometer or a Scanning Electron Microscope.[20]

- Permeability

- The separator must not limit performance. Polymer separators typically increase the resistance of the electrolyte by a factor of four to five. The ratio of the resistance of the electrolyte-filled separator to the resistance of the electrolyte alone is called the MacMullin number. Air permeability can be used indirectly to estimate the MacMullin number. Air permeability is expressed in terms of the Gurley value, the time required for a specified amount of air to pass through a specified area of the separator under a specified pressure. The Gurley value reflects the tortuosity of the pores, when the porosity and thickness of the separator is fixed. A separator with uniform porosity is vital to battery life cycle. Deviations from uniform permeability produce uneven current density distribution, which causes the formation of crystals on the anode.[21][22]

- Mechanical strength

There are multiple factors that contribute to the overall mechanical profile of a separator.

Tensile strength

[edit]- The separator must be strong enough to withstand the tension of the winding operation during battery assembly. Additionally, the separator must not change dimensions from a tensile stress, or the cathode and anode could come into contact, shorting the battery. Tensile strength is typically defined in both the machine (winding) direction and the transverse direction, in terms of Young’s modulus.[23] Large Young’s moduli in the machine direction provide dimensional stability, as strain is inversely proportional to strength.:[24] Tensile strength is highly dependent on separator processing and final microstructure. Dry processed separators have anisotropic strength profiles, having the greatest strength in the machine direction, due to the orientation of the fibrils that form via a crazing mechanism during processing. Wet processed separators have a more isotropic strength profile, having comparable values in both machine and transverse directions.[25][26][27]

Puncture strength

[edit]- To prevent electrical shorting (battery failure), the separator must not yield to stresses applied by particles or structures on its surface. Puncture strength is defined as applied force needed to force a probe through the separator.[24]

- Wettability

- The electrolyte must fill the entire battery assembly, requiring the separator to "wet" easily with the electrolyte. Furthermore, the electrolyte should be able to permanently wet the separator, preserving the cycle life. There is no generally accepted method used to test wettability, other than observation.[28]

- Thermal stability

- The separator must remain stable over a wide temperature range without curling or puckering, laying completely flat.[29]

- Thermal shutdown

- Separators in lithium-ion batteries must offer the ability to shut down at a temperature slightly lower than that at which thermal runaway occurs, while retaining its mechanical properties.[5]

Defects

[edit]Many structural defects can form in polymer separators due to temperature changes. These structural defects can result in a thicker separators. Furthermore, there can be intrinsic defects in the polymers themselves, such as polyethylene often begins to deteriorate during the stages of polymerization, transportation, and storage.[30] Additionally, defects such as tears or holes can form during the synthesis of polymer separators. There are also other sources of defects can come from doping the polymer separator.[2]

Use in Li-ion Batteries

[edit]Polymer separators, similar to battery separators in general, act as a separator of the anode and cathode in the Li-ion battery while also enabling the movement of ions through the cell. Additionally, many of the polymer separators, typically multilayer polymer separators, can act as “shutdown separators”, which are able to shut down the battery if it becomes too hot during the cycling process. These multilayered polymer separators are generally composed of one or more polyethylene layers which serve to shut down the battery and at least one polypropylene layer which acts as a form of mechanical support for the separator.[6][31]

Separators are also subjected to numerous stresses during battery assembly and battery usage. Common stresses include tensile stresses from dry/wet processes and compressive stresses from the volumetric expansion of electrodes and required forces to ensure sufficient contact between components. Dendritic lithium growths are another common source of stress. These stresses are often applied concurrently, creating a complex stress field that separators must withstand. Additionally, standard battery operation leads to the cyclic application of these stresses. These cyclic conditions can mechanically fatigue separators, which reduces strength, leading to eventual device failure.[32]

Other types of battery separators

[edit]In addition to polymer separators, there are several other types of separators. There are nonwovens, which consist of a manufactured sheet, web, or mat of directionally or randomly oriented fibers. Supported liquid membranes, which consist of a solid and liquid phase contained within a microporous separator. Additionally there are also polymer electrolytes which can form complexes with different types of alkali metal salts, which results in the production of ionic conductors which serve as solid electrolytes. Another type of separator, a solid ion conductor, can serve as both a separator and the electrolyte in a battery.[10]

Plasma technology was used to modify a polyethylene membrane for enhanced adhesion, wettability and printability. These are usually performed by modifying the membrane on only its outermost several molecular levels. This allows the surface to behave differently without modifying the properties of the remainder. The surface was modified with acrylonitrile via a plasma coating technique. The resulting acrylonitrile-coated membrane was named PiAn-PE. The surface characterization demonstrated that PiAN-PE's enhanced adhesion resulted from the increased polar component of surface energy.[33]

The sealed rechargeable nickel-metal hydride battery offers significant performance and environmental friendliness above alkaline rechargeable batteries. Ni/MH, like the lithium-ion battery, provides high energy and power density with long cycle lives. This technology's greatest problem is its inherent high corrosion rate in aqueous solutions. The most commonly used separators are porous insulator films of polyolefin, nylon or cellophane. Acrylic compounds can be radiation-grafted onto these separators to make their properties more wettable and permeable. Zhijiang Cai and co-workers developed a solid polymer membrane gel separator. This was a polymerization product of one or more monomers selected from the group of water-soluble ethylenically unsaturated amides and acid. The polymer-based gel also includes a water swellable polymer, which acts as a reinforcing element. Ionic species are added to the solution and remain embedded in the gel after polymerization.

Ni/MH batteries of bipolar design (bipolar batteries) are being developed because they offer some advantages for applications as storage systems for electric vehicles. This solid polymer membrane gel separator could be useful for such applications in bipolar design. In other words, this design can help to avoid short-circuits occurring in liquid-electrolyte systems.[34]

Inorganic polymer separators have also been of interest as use in lithium-ion batteries. Inorganic particulate film/poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)/inorganic particulate film trilayer separators are prepared by dip-coating inorganic particle layers on both sides of PMMA thin films. This inorganic trilayer membrane is believed to be an inexpensive, novel separator for application in lithium-ion batteries from increased dimensional and thermal stability.[35]

References

[edit]- ^ Flaim, Tony; Wang, Yubao; Mercado, Ramil (2004). "High-refractive-index polymer coatings for optoelectronics applications". In Amra, Claude; Kaiser, Norbert; MacLeod, H. Angus (eds.). Advances in Optical Thin Films. Vol. 5250. p. 423. Bibcode:2004SPIE.5250..423F. doi:10.1117/12.513363. S2CID 27478564.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ a b Arora, Pankaj; Zhang, Zhengming (John) (2004). "Battery Separators". Chemical Reviews. 104 (10): 4419–4462. doi:10.1021/cr020738u. PMID 15669158. S2CID 20944844.

- ^ a b Choi, Sung-Seen; Lee, Young Soo; Joo, Chang Whan; Lee, Seung Goo; Park, Jong Kyoo; Han, Kyoo-Seung (2004). "Electrospun PVDF nanofiber web as polymer electrolyte or separator". Electrochimica Acta. 50 (2–3): 339–343. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2004.03.057.

- ^ Licari, J. J.; Weigand, B. L. (1980). "Solvent-Removable Coatings for Electronic Applications". Resins for Aerospace. ACS Symposium Series. Vol. 123. pp. 127–37. doi:10.1021/bk-1980-0132.ch012. ISBN 0-8412-0567-1.

- ^ a b Chung, Y. S.; Yoo, S. H.; Kim, C. K. (2009). "Enhancement of Meltdown Temperature of the Polyethylene Lithium-Ion Battery". Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Research. 48 (9): 4346–351. doi:10.1021/ie900096z.

- ^ a b c Li, S. L.; Ai, X. P.; Yang, H. X.; et al. (2009). "A polytriphenylamine-modified separator with reversible overcharge protection for 3.6 V-class lithium-ion battery". Journal of Power Sources. 189 (1): 771–774. Bibcode:2009JPS...189..771L. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2008.08.006.

- ^ "Ceramic Separators for Lithium-ion Battery Manufacturing & Research". Targray. August 1, 2016.

- ^ Munshi, M. Z. A. (1995). Handbook of Solid State Batteries & Capacitors. Singapore: World Scientific. ISBN 981-02-1794-3.

- ^ a b Zhang, S. S. (2007). "A review on the separators of liquid electrolyte Li-ion batteries". Journal of Power Sources. 164 (1): 351–364. Bibcode:2007JPS...164..351Z. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2006.10.065.

- ^ a b Wang, L. C.; Harvey, M. K.; Ng, J. C.; Scheunemann, U. (1998). "Ultra-high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMW-PE) and its application in microporous separators for lead/acid batteries". Journal of Power Sources. 73 (1): 74–77. Bibcode:1998JPS....73...74W. doi:10.1016/S0378-7753(98)00023-8.

- ^ a b c d Huang, Xiaosong (2011). "Separator technologies for lithium-ion batteries". Journal of Solid State Electrochemistry. 15 (4): 649–662. doi:10.1007/s10008-010-1264-9. S2CID 96873960.

- ^ a b Jeon, M. Y.; Kim, C. K. (2007). "Phase Behavior of Polymer/diluent/diluent Mixtures and Their Application to Control Microporous Membrane Structure". Journal of Membrane Science. 300 (1–2): 172–81. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2007.05.022.

- ^ Ozawa, Kazunori (2009). Lithium Ion Rechargeable Batteries: Materials, Technology, and New Applications. Weinheim: Wiley. ISBN 978-3-527-31983-1.

- ^ Zhang, S. S.; Ervin, M. H.; Xu, K.; et al. (2004). "Microporous polyacrylonitrile-methyl methacrylate membrane as a separator of rechargeable lithium battery". Electrochimica Acta. 49 (20): 3339–3345. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2004.02.045.

- ^ Lee, J. Y.; Lee, Y. M.; Bhattacharya, B.; et al. (2009). "Separator grafted with siloxane by electron beam irradiation for lithium secondary batteries". Electrochimica Acta. 54 (18): 4312–4315. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2009.02.088.

- ^ a b Gwon, S. J.; Choi, J. H.; Sohn, J. Y.; et al. (2009). "Preparation of a new micro-porous poly(methyl methacrylate)-grafted polyethylene separator for high performance Li secondary battery". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B. 267 (19): 3309–3313. Bibcode:2009NIMPB.267.3309G. doi:10.1016/j.nimb.2009.06.117.

- ^ a b Jeong, Yeon-Bok; Kim, Dong-Won (2004). "Cycling Performances of Li/LiCoO2 Cell with Polymer-coated Separator". Electrochimica Acta. 50 (2–3): 323–26. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2004.01.098.

- ^ Nikolou, Maria; Dyer, Aubrey; Steckler, Timothy; Donoghue, Evan; Wu, Zhuangchun; Heston, Nathan; Rinzler, Andrew; Tanner, David; Reynolds, John (2009). "Dual n- and p-Type Dopable Electrochromic Devices Employing Transparent Carbon Nanotube Electrodes". Chemistry of Materials. 21 (22): 5539–5547. doi:10.1021/cm902768q.

- ^ Pitet, Louis M.; Amendt, Mark A.; Hillmyer, Marc A. (2010). "Nanoporous Linear Polyethylene from a Block Polymer Precursor". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 132 (24): 8230–8231. Bibcode:2010JAChS.132.8230P. doi:10.1021/ja100985d. PMID 20355700.

- ^ Vidu, Ruxandra; Stroeve, Pieter (2004). "Improvement of the Thermal Stability of Li-Ion Batteries by Polymer Coating of LiMn2O4". Industrial & Engineering Chemistry Research. 43 (13): 3314–3324. doi:10.1021/ie034085z. S2CID 95541458.

- ^ Kim, J. Y.; Lim, D. Y. (2010). "Surface-Modified Membrane as A Separator for Lithium-Ion Polymer Battery". Energies. 3 (4): 866–885. doi:10.3390/en3040866. hdl:1721.1/65084.

- ^ Yoo, S. H.; Kim, C. K. (2009). "Enhancement of the Meltdown Temperature of a Lithium Ion Battery Separator". Industrial and Engineering Chemistry Research. 48 (22): 9936–9941. doi:10.1021/ie901141u.

- ^ Scrosati, Bruno (1993). Applications of Electroactive Polymers. London: Chapman & Hall. ISBN 0-412-41430-9.

- ^ a b Baldwin, Richard; Bennett, William; Wong, Eunice; Lewton, MaryBeth; Harris, Megan (2010). "Battery Separator Characterization and Evaluation Procedures for NASA's Advanced Lithium-Ion Batteries" (PDF). NASA.

- ^ Kalnaus, Sergiy; Wang, Yanli; Turner, John (April 30, 2017). "Mechanical behavior and failure mechanisms of Li-ion battery separators". Journal of Power Sources. 348: 255–263. Bibcode:2017JPS...348..255K. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.03.003.

- ^ Zhang, Xiaowei; Sahraei, Elham; Wang, Kai (September 30, 2016). "Deformation and failure characteristics of four types of lithium-ion battery separators". Journal of Power Sources. 327: 693–701. Bibcode:2016JPS...327..693Z. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2016.07.078.

- ^ Polymer Properties Database (2021). "Fracture of Glassy Polymers: Cavitation and Crazing". Polymer Properties Database. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ Stroeve, Pieter; Balazs, Anna C., eds. (1992-06-10). "Macromolecular Assemblies in Polymeric Systems". ACS Symposium Series. Vol. 493. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society. pp. 1–7. doi:10.1021/bk-1992-0493.ch001. ISBN 978-0-8412-2427-8.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Sohn, Joon-Yong; Gwon, Sung-Jin; Choi, Jae-Hak; Shin, Junhwa; Nho, Young-Chang (2008). "Preparation of Polymer-coated Separators Using an Electron Beam Irradiation". Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B. 266 (23): 4994–5000. Bibcode:2008NIMPB.266.4994S. doi:10.1016/j.nimb.2008.09.002.

- ^ Koval’, E. O.; Kolyagin, V. V.; Klimov, I. G.; Maier, E. A. (2010). "Investigation of the influence of technological factors on quality of basic brands of HPPE". Russian Journal of Applied Chemistry. 83 (6): 1115–1120. doi:10.1134/S1070427210060406. S2CID 96094869.

- ^ Feng, J. K.; Ai, X. P.; Cao, Y. L.; et al. (2006). "Polytriphenylamine used as an electroactive separator material for overcharge protection of rechargeable lithium battery". Journal of Power Sources. 161 (1): 545–549. Bibcode:2006JPS...161..545F. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2006.03.040.

- ^ Zhang, X.; Zhu, J.; Sahraei, E. (December 4, 2017). "Degradation of battery separators under charge-discharge cycles". RSC Advances. 7 (88): 56099–56107. Bibcode:2017RSCAd...756099Z. doi:10.1039/c7ra11585g.

- ^ Kim, J. Y. (2009). "Plasma-modified polyethylene membranes as a separator for lithium-ion polymer battery". Electrochimica Acta. 54 (14): 3714–3719. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2009.01.055.

- ^ Cai, Z. (2004). "Possible application of novel solid polymer membrane gel separator in nickel/metal hydride battery". Journal of Materials Science. 39 (2): 703–705. Bibcode:2004JMatS..39..703C. doi:10.1023/B:JMSC.0000011536.48992.43. S2CID 95783141.

- ^ Kim, M.; Han, G. Y.; Yoon, K. J.; Park, J. Y. (2010). "Preparation of a trilayer separator and its application to lithium-ion batteries". Journal of Power Sources. 195 (24): 8302–8305. Bibcode:2010JPS...195.8302K. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2010.07.016.