Plagues of Egypt: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 90.207.161.63 to version by Elizium23. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1734255) (Bot) |

|||

| Line 129: | Line 129: | ||

In visual art, the plagues have generally been reserved for works in series, especially engravings. Still, relatively few depictions in art emerged compared to other religious themes. The plagues became more common subjects in the 19th century, with [[John Martin (painter)|John Martin]] and [[J. M. W. Turner|Joseph Turner]] producing notable canvases. This trend probably reflected a Romantic attraction to landscape and nature painting, for which the plagues were suited, a Gothic attraction to morbid stories, and a rise in Orientalism, wherein exotic Egyptian themes found currency. Given the importance of noble patronage throughout Western art history, the plagues may have found consistent disfavor because the stories emphasize the limits of a monarch's power, and images of lice, locusts, darkness, and boils were ill-suited for decoration in palaces and churches.{{citation needed|date=June 2012}} |

In visual art, the plagues have generally been reserved for works in series, especially engravings. Still, relatively few depictions in art emerged compared to other religious themes. The plagues became more common subjects in the 19th century, with [[John Martin (painter)|John Martin]] and [[J. M. W. Turner|Joseph Turner]] producing notable canvases. This trend probably reflected a Romantic attraction to landscape and nature painting, for which the plagues were suited, a Gothic attraction to morbid stories, and a rise in Orientalism, wherein exotic Egyptian themes found currency. Given the importance of noble patronage throughout Western art history, the plagues may have found consistent disfavor because the stories emphasize the limits of a monarch's power, and images of lice, locusts, darkness, and boils were ill-suited for decoration in palaces and churches.{{citation needed|date=June 2012}} |

||

Perhaps the most successful artistic representation of the plagues is [[George Frideric Handel|Handel's]] oratorio "[[Israel in Egypt]]" which, like his perennial favorite, Messiah, takes a libretto entirely from scripture. The work was especially popular in the 19th century because of its numerous choruses, generally one for each plague, and its playful musical depiction of the plagues. For example, the plague of frogs is a light aria for alto depicting frog's jumping in the violins, and the plague of flies/lice is a light chorus with fast scurrying runs in the violins.{{citation needed|date=June 2012}} |

Perhaps the most successful artistic representation of the plagues is [[George Frideric Handel|Handel's]] oratorio "[[Israel in Egypt]]" which, like his perennial favorite, Messiah, takes a libretto entirely from scripture. The work was especially popular in the 19th century because of its numerous choruses, generally one for each plague, and its playful musical depiction of the plagues. For example, the plague of frogs is a light aria for alto depicting frog's jumping in the violins, and the plague of flies/lice is a light chorus with fast scurrying runs in the violins.{{citation needed|date=June 2012}} |

||

I love butts |

|||

===Children's books about the ten plagues=== |

===Children's books about the ten plagues=== |

||

Revision as of 17:55, 25 September 2013

The Plagues of Egypt (Hebrew: מכות מצרים, Makot Mitzrayim), also called the Ten Plagues (Hebrew: עשר המכות, Eser HaMakot) or the Biblical Plagues, were ten calamities that, according to the biblical Book of Exodus, Israel's God, Yahweh, inflicted upon Egypt to persuade Pharaoh to release the ill-treated Israelites from slavery. Pharaoh capitulated after the tenth plague, triggering the Exodus of the Jewish people. The plagues were designed to contrast the power of Yahweh with the impotence of Egypt's various gods.[1] Some commentators have associated several of the plagues with judgment on specific gods associated with the Nile, fertility and natural phenomena.[2] The plagues of Egypt are also mentioned in the Quran (7,133–136).[3] According to the Book of Exodus, God proclaims that all the gods of Egypt will be judged through the tenth and final plague:

"On that same night I will pass through Egypt and strike down every firstborn — both men and animals —and I will bring judgment on all the gods of Egypt. I am the LORD"

Context

The reason for the plagues appears to be twofold:[4] to answer Pharaoh's taunt, “Who is Yahweh, that I should obey his voice to let Israel go?”[5] and to indelibly impress the Israelites with Yahweh's power as an object lesson for all time, which was also meant to become known “throughout the world”.[6][7]

According to the Torah, God hardened Pharaoh's heart so he would be strong enough to persist in his unwillingness to release the people, so that God could manifest his great power and cause it to be declared among the nations,[8] so that other people would discuss it for generations afterward.[9] In this view, the plagues were punishment for the Egyptians' long abuse of the Israelites, as well as proof that the gods of Egypt were powerless by comparison.[10] If God triumphed over the gods of Egypt, a world power at that time, then the people of God would be strengthened in their faith, although they were a small people, and would not be tempted to follow the deities that God put to shame. Exodus portrays Yahweh explaining why he did not accomplish the freedom of the Israelites immediately:

I could have stretched forth My hand and stricken you [Pharaoh] and your people with pestilence, and you would have been effaced from the earth. Nevertheless I have spared you for this purpose: in order to show you My power and in order that My fame may resound throughout the world.

— Exodus 9:15–16 (JPS)

Biblical narrative

Moses and Aaron approached the Pharaoh, and to deliver God's demand that the Israelite slaves be allowed to leave Egypt so that they could worship God freely. After an initial refusal by the Pharaoh, God sent Moses and Aaron back to show him a miraculous sign of warning – Moses's rod turned into a serpent. Pharaoh's sorcerers also turned their staffs into snakes, but Aaron's then proceeded to swallow theirs before turning back into a staff.

The interval of time within which the plagues occurred cannot be stated with certainty.[11]

The first three plagues seemed to affect "all the land of Egypt,"[12] while the 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, and 9th did not affect the children of Israel.[13] Conditions of the 8th plague are unclear. For the last plague the Torah indicates that they were only spared from the final plague by sacrificing the Paschal lamb, marking their place directly above their doors with the lamb's blood, and eating the roasted sacrifice together with Matzot (לחם עוני) in a celebratory feast. The Torah describes God as actually passing through Egypt to kill all firstborn children, but passing over (hence "Passover") houses which have the sign of lambs' blood on the doorpost.[14][15] It is debated whether it was actually God who came through the streets or one of his angels. Some also think it may be the Holy Spirit. It is most commonly known as the "Angel of Death". The night of this plague, Pharaoh finally relents and sends the Israelites away under their terms.

After the Israelites leave en masse, a departure known as The Exodus, Yahweh introduces himself by name and makes an exclusive covenant with the Israelites on the basis of this miraculous deliverance.[16] The Ten Commandments encapsulate the terms of this covenant.[17] Joshua, the successor to Moses, reminds the people of their deliverance through the plagues.[18] According to 1 Samuel, the Philistines also knew of the plagues and feared their author.[19][20] Later, the psalmist sang of these events.[21]

The Torah[22] also relates God's instructions to Moses that the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt must be celebrated early on the holiday of Passover (Pesaḥ פסח); the rituals observed on Passover recall the events surrounding the exodus from Egypt. The Torah additionally cites God's sparing of the Israelite firstborn as a rationale for the commandment of the redemption of the firstborn.[23] This event is also commemorated by the fast of the firstborn on the day preceding Passover but which is traditionally not observed because a siyum celebration is held which obviates the need for a fast.

It seems that the celebration of Passover waned from time to time, since other biblical books provide references to revival of the holiday.[24] For example, it was reinstated by Joshua at Gilgal,[25] by Josiah,[26] by Hezekiah[27] and, after the return from the captivity, by Ezra.[28] By the time of the Second Temple it was firmly established in Israel.

Plagues

The plagues as they appear in the Book of Exodus are:[29]

1. Plague of blood (דָם): Ex. 7:14–25

This is what the LORD says: By this you will know that I am the LORD: With the staff that is in my hand I will strike the water of the Nile, and it will be changed into blood. The fish in the Nile will die, and the river will stink and thus the Egyptians will not be able to drink its water.

— Exodus 7:17–18

God instructed Moses to dip the top of his staff in the river Nile; all of its water turned into blood. As a result of the blood, the fish of the Nile died, filling Egypt with an awful stench. Other water resources used by the Egyptians were turned to blood as well (7:19). Pharaoh's sorcerers demonstrated that they too could turn water into blood, and Pharaoh therefore made no concession to Moses' demands.

2. Plague of frogs (צְּפַרְדֵּעַ): Ex. 7:25–8:11

This is what the great LORD says: Let my people go, so that they may worship me. If you refuse to let them go, I will plague your whole country with frogs. The Nile will teem with frogs. They will come up into your palace and your bedroom and onto your bed, into the houses of your officials and on your people, and into your ovens and kneading troughs. The frogs will go up on you and your people and all your officials.

— Exodus 8:1–4

The second plague of Egypt was frogs. God commanded Moses to tell Aaron to stretch the staff over the water, and hordes of frogs came and overran Egypt. Pharaoh's sorcerers were also able to duplicate this plague with their magic. However, since they were unable to remove it, Pharaoh was forced to grant permission for the Israelites to leave so that Moses would agree to remove the frogs. To prove that the plague was actually a divine punishment, Moses let Pharaoh choose the time that it would end. Pharaoh chose the following day, and all the frogs died the next day. Nevertheless, Pharaoh rescinded his permission, and the Israelites stayed in Egypt.

3. Plague of lice or gnats (כִּנִּים): Ex. 8:16–19

Then the LORD said […] "Stretch out thy rod, and smite the dust of the land, that it may become lice throughout all the land of Egypt." […] When Aaron stretched out his hand with the staff and struck the dust of the ground, gnats came upon men and animals. All the dust throughout the land of Egypt became lice.

— Exodus 8:16–17

The Hebrew noun could be translated as lice, gnats, or fleas.[30] God instructed Moses to tell Aaron to take the staff and strike at the dust, which turned into a mass of lice that the Egyptians could not get rid of. The Egyptian sorcerers declared that this act was "the finger of God" since they were unable to reproduce its effects with their magic.

4. Plague of flies or wild animals (עָרוֹב): Ex. 8:20–32

This is what the LORD says: Let my people go, so that they may worship me. If you do not let my people go, I will send swarms of flies upon you and your officials, on your people and into your houses. The houses of the Egyptians will be full of flies, and even the ground where they are.

— Exodus 8:20–21

The fourth plague of Egypt was of animals capable of harming people and livestock. The Torah emphasizes that the arov ("mixture" or "swarm") only came against the Egyptians, and that it did not affect the Land of Goshen (where the Israelites lived). Pharaoh asked Moses to remove this plague and promised to allow the Israelites' freedom. However, after the plague was gone, the LORD "hardened Pharaoh's heart," and he refused to keep his promise.[31]

The word עָרוֹב has caused a difference of opinion among traditional interpreters.[31] The root meaning is related to "mixing".[32] While most traditional interpreters understand the plague as "wild animals",[33] Gesenius along with many modern interpreters understand the plague as a swarm of flies.[34]

5. Plague of pestilence (דֶּבֶר): Ex. 9:1–7

This is what the LORD, the God of the Hebrews, says: "Let my people go, so that they may worship me." If you refuse to let them go and continue to hold them back, the hand of the LORD will bring a terrible plague on your livestock in the field—on your horses and donkeys and camels and on your cattle and sheep and goats.

— Exodus 9:1–3

The fifth plague of Egypt was an epidemic disease which exterminated the Egyptian livestock; that is, horses, donkeys, camels, cattle, sheep and goats. The Israelites' cattle were unharmed. Once again, Pharaoh made no concessions.

6. Plague of boils (שְׁחִין): Ex. 9:8–12

The sixth plague of Egypt was shkhin, a kind of skin disease, usually translated as "boils". God commanded Moses and Aaron to each take two handfuls of soot from a furnace, which Moses scattered skyward in Pharaoh's presence. The soot induced festering Shkhin eruptions on Egyptian men and livestock. The Egyptian sorcerers were afflicted along with everyone else, and were unable to heal themselves, much less the rest of Egypt.

7. Plague of hail (בָּרָד): Ex. 9:13–35

This is what the LORD, the God of the Hebrews, says: Let my people go, so that they may worship me, or this time I will send the full force of my plagues against you and against your officials and your people, so you may know that there is no one like me in all the earth. For by now I could have stretched out my hand and struck you and your people with a plague that would have wiped you off the earth. But I have raised you up for this very purpose, that I might show you my power and that my name might be proclaimed in all the earth. You still set yourself against my people and will not let them go. Therefore, at this time tomorrow I will send the worst hailstorm that has ever fallen on Egypt, from the day it was founded till now. Give an order now to bring your livestock and everything you have in the field to a place of shelter, because the hail will fall on every man and animal that has not been brought in and is still out in the field, and they will die. […] The LORD sent thunder and hail, and lightning flashed down to the ground. So the LORD rained hail on the land of Egypt; hail fell and lightning flashed back and forth. It was the worst storm in all the land of Egypt since it had become a nation.

— Exodus 9:13–24

The seventh plague of Egypt was a destructive storm. God commanded Moses to stretch his staff skyward, at which point the storm commenced. It was even more evidently supernatural than the previous plagues, a powerful shower of hail intermixed with fire. The storm heavily damaged Egyptian orchards and crops, as well as people and livestock. The storm struck all of Egypt except for the Land of Goshen. Pharaoh asked Moses to remove this plague and promised to allow the Israelites to worship God in the desert, saying "This time I have sinned; God is righteous, I and my people are wicked." As a show of God's mastery over the world, the hail stopped as soon as Moses began praying to God. However, after the storm ceased, Pharaoh again "hardened his heart" and refused to keep his promise.

8. Plague of locusts (אַרְבֶּה): Ex. 10:1–20

This is what the LORD,the God of the Hebrews, says: 'How long will you refuse to humble yourself before me? Let my people go, so that they may worship me. If you refuse to let them go, I will bring locusts into your country tomorrow. They will cover the face of the ground so that it cannot be seen. They will devour what little you have left after the hail, including every tree that is growing in your fields. They will fill your houses and those of all your officials and all the Egyptians—something neither your fathers nor your forefathers have ever seen from the day they settled in this land till now.

— Exodus 10:3–6

It began day 1 of the Hebrew Month of Shevat: The eighth plague of Egypt was locusts. Before the plague, God informed Moses that from that point on He would "harden Pharaoh's heart," (as promised earlier in 4:21) so that Pharaoh would not give in, and the remaining miracles (the final plagues and the splitting of the sea) would play out.

As with previous plagues, Moses came to Pharaoh and warned him of the impending plague of locusts. Pharaoh's officials begged him to let the Israelites go rather than suffer the devastating effects of a locust-swarm, but he was still unwilling to give in. He proposed a compromise: the Israelite men would be allowed to go, while women, children and livestock would remain in Egypt. Moses repeated God's demand that every last person and animal should go, but Pharaoh refused.

God then had Moses stretch his staff over Egypt, and a wind picked up from the east. The wind continued until the following day, when it brought a locust swarm. The swarm covered the sky, casting a shadow over Egypt. It consumed all the remaining Egyptian crops, leaving no tree or plant standing. Pharaoh again asked Moses to remove this plague and promised to allow all the Israelites to worship God in the desert. As promised, God sent a wind that blew the locusts into the Red Sea. However, He also hardened Pharaoh's heart, and he did not allow the Israelites to leave.

9. Plague of darkness (חוֹשֶך): Ex. 10:21–29

Then the LORD said to Moses, "Stretch out your hand toward the sky so that darkness will spread over Egypt—darkness that can be felt." So Moses stretched out his hand toward the sky, and total darkness covered all Egypt for three days. No one could see anyone else or leave his place for three days.

— Exodus 10:21–23

In the ninth plague, God commanded Moses to stretch his hands up to the sky, to bring darkness upon Egypt. This darkness was so heavy that an Egyptian could physically feel it. They couldn't work or do activities. They were unable to track time for lack of light and they even had a hard time interacting with each other. The Egyptians had to rely on the senses of touch and hearing.[dubious – discuss] [citation needed] It lasted for three days, during which time there was light in the homes of the Israelites. Pharaoh then called to Moses and offered to let all the Israelites leave, if only the darkness would be removed from his land. However, he required that their sheep and cattle stay. Moses refused any compromise, and went on to say that Pharaoh must allow them to take also the animals because they are needed for sacrifice. Pharaoh, enraged, then threatened to execute Moses if he should again appear before Pharaoh. Moses replied that he would indeed not visit the Pharaoh again.

This plague was an attack aimed directly at Pharaoh's god Ra, the Egyptian sun god. By introducing the plague of darkness, Moses attempted to demonstrate the clear power of Yahweh; and the folly of worshipping the Egyptian gods.

10. Death of the firstborn (מַכַּת בְּכוֹרוֹת): Ex. 11:1–12:36

This is what the LORD says: 'About midnight I will go throughout Egypt. Every firstborn in Egypt will die, from the firstborn son of Pharaoh, who sits on the throne, to the firstborn of the slave girl, who is at her hand mill, and all the firstborn of the cattle as well. There will be loud wailing throughout Egypt—worse than there has ever been or ever will be again.'

— Exodus 11:4–6

Before this final plague, God commanded Moses to inform all the Israelites to mark lamb's blood on the doorposts on every door in which case the LORD will pass over them and not "suffer the destroyer to come into your houses and smite you" (chapter 12, v. 23), thus sparing all the Israelite first-borns. This was the hardest blow upon Egypt and the plague that finally convinced Pharaoh to submit, and let the Israelites go.

After this, Pharaoh, furious, saddened, and afraid that he would be killed next, ordered the Israelites to go away, taking whatever they wanted. The Israelites did not hesitate, believing that soon Pharaoh would once again change his mind, which he did; and at the end of that night Moses led them out of Egypt with "arms upraised".[35]

Scholarly interpretation

The story of the plagues is heavily reliant on the Deuteronomistic history and the prophetic books of Amos, Isaiah and Ezekiel, suggesting that it was composed in 6th century BCE at the earliest. The book of Deuteronomy, in which Moses reviews the events of the past, mentions the "diseases of Egypt" (Deuteronomy 7:15 and 28:60), but means something that afflicted the Israelites, not the Egyptians; in fact it never mentions the plagues of the book of Exodus. The Exodus plagues are divine judgments, a series of curses like those in Deuteronomy 28:15–68, which mention many of the same afflictions; they are even closer to the curses in the Holiness code, Leviticus 26, since like the Holiness Code they leave room for repentance. The theme that divine punishment should lead to repentance comes from the prophets (Amos 4:6–12, Ezekiel 20), and the form of prophetic speech, "Thus says Yahweh", and the figure of the prophet as divine messenger, are from the late prophets Jeremiah and Ezekiel and the Deuteronomistic history (all compositions of the 6th century). The theme of Pharaoh's obstinacy is likewise derived from the 6th century prophets – Isaiah 6:9–13, Jeremiah 5:3, and Ezekiel 3:7–9.[36]

Historicity

Historians assert that the plague stories are mythical, allegorical, and inspired by passed-down accounts of disconnected natural disasters. Scientists claim the plagues can be attributed to a chain of natural phenomena triggered by changes in the climate and environmental disasters hundreds of miles away.[37]

Archaeology

Archaeologists now widely believe the plagues occurred at the ancient city of Pi-Rameses in the Nile Delta, which was the capital of Egypt during the reign of Rameses II.[37] There is archaeological material that some archaeologists, such as William F. Albright, have considered historical evidence of the Ten Plagues; for example, an ancient water-trough found in El Arish bears hieroglyphic markings detailing a period of darkness. Albright, and other Christian archaeologists have claimed that such evidence, as well as careful study of the areas ostensibly traveled by the Israelites after the Exodus, make discounting the Biblical account untenable. The Egyptian Ipuwer papyrus describes a series of calamities befalling Egypt, including a river turned to blood, men behaving as wild ibises, and the land generally turned upside down. However, this is usually thought to describe a general and long term ecological disaster lasting for a period of decades, such as that which destroyed the Old Kingdom. The document is usually dated to the end of the Middle Kingdom, or more rarely, to its beginning, fitting the Old Kingdom destruction, but in both cases long before the usual theorized dates for the Exodus.

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2011) |

Natural explanations

Historians have suggested that the plagues are passed-down accounts of several natural disasters, some disconnected, others playing part of a chain reaction. Natural explanations have been suggested for most of the phenomena:

- 1 —water turned into blood; fish died)

- Dr. Stephen Pflugmacher, a biologist at the "Leibniz Institute for Water Ecology and Inland Fisheries" in Berlin believes that rising temperatures could have turned the Nile into a slow-moving, muddy watercourse -conditions favorable for the spread of toxic fresh water algae. As the bacterium, known as Burgundy Blood algae, dies. it turns the water red.[37]

- Alternatively, a bloody appearance could be due to an environmental change, such as a drought, which could have contributed to the spread of the Chromatiaceae bacteria which thrive in stagnant, oxygen-deprived water.[38]

- (plague 2—frogs) Any blight on the water that killed fish also would have caused frogs to leave the river and probably die.

- (plagues 3 and 4—biting insects and flies) The lack of frogs in the river would have let insect populations, normally kept in check by the frogs, increase massively. The rotting corpses of fish and frogs would have attracted significantly more insects to the areas near the Nile.

- (plagues 5 and 6—livestock disease and boils) There are biting flies in the region which transmit livestock diseases; a sudden increase in their number could spark epidemics.

- (plague 7—fiery hail)

- 8 -locusts

- According to the UN Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO), when they get hungry, a one-ton horde of locusts can eat the same amount of food in one day as 2,500 humans, according to the UN.[39]

- 9 —darkness

- The immediate cause of this plague was probably the "hamsin", a south or south-west wind charged with sand and dust, which blows about the spring equinox and at times produces darkness rivaling that of the worst London fogs.[11]

- (plague 10—death of the firstborn)

- If the last plague indeed selectively tended to affect the firstborn, it could be due to food polluted during the time of darkness, either by locusts or by the black mold Cladosporium. When people emerged after the darkness, the firstborn would be given priority, as was usual, and would consequently be more likely to be affected by any toxin or disease carried by the food. Meanwhile, the Israelites ate food prepared and eaten very quickly which would have made it less likely to be infected.

- In the 2006 documentary Exodus Decoded, filmmaker Simcha Jacobovici hypothesised the selectiveness of the tenth plague was under the circumstances similar to the 1986 disaster of Lake Nyos that is related to geological activities that caused the previous plagues in a related chain of events. The hypothesis was that the plagues took place shortly after the eruption of Thera (now known as Santorini), which happened some time between 1550 BCE and 1650 BCE, and recently narrowed to between 1627–1600 BCE, with a 95% probability of accuracy. Jacobovici however places the eruption in 1500 BCE. According to the documentary, the eruption sets off a chain of events resulting in the plagues and eventually the killing of the first born. Jacobovici suggests that the first borns in ancient Egypt had the privilege to sleep close to the floor while other children slept on higher ground or even on roofs. This view, however, is not supported by any archaeological or historical evidence. As in Lake Nyos, when carbon dioxide or other toxic gases escape the surface tension of a nearby waterbody because of either geological activity or over-saturation, the gas, being heavier than air, "flooded" the nearby area displacing oxygen and killing those who were in its path.

A volcanic eruption which happened in antiquity and could have caused some of the plagues if it occurred at the right time is the eruption of the Thera volcano 1,050 kilometres (650 mi) to the northwest of Egypt. Controversially dated to about 1628 BC, this eruption is one of the largest on record, rivaling that of Tambora, which resulted in 1816's Year Without a Summer. The enormous global impact of this eruption has been recorded in an ash layer deposit found in the Nile delta, tree ring frost scars in the bristlecone pines of the western United States, and a coating of ash in the Greenland ice caps, all dated to the same time and with the same chemical fingerprint as the ash from Thera.

However, all estimates of the date of this eruption are hundreds of years before the Exodus is believed to have taken place; thus the eruption can only have caused some of the plagues if one or other of the dates is wrong, or if the plagues did not actually immediately precede the Exodus.

Following the assumption that at least some of the details are accurately reported, many modern Jews believe that some of the plagues were indeed natural disasters, but argue for the fact that, since they followed one another with such uncommon rapidity, "God's hand was behind them". Indeed, several Biblical commentators (Nachmanides and, more recently, Rabbi Yaakov Kamenetzky) have pointed out that, for the plagues to be a real test of faith, they had to contain an element leading to religious doubt.

In his book The Plagues of Egypt: Archaeology, History, and Science Look at the Bible, Siro Igino Trevisanato explores the theory that the plagues were initially caused by the Santorini eruption in Greece. His hypothesis considers a two-stage eruption over a time of a bit less than two years. His studies place the first eruption in 1602 BC, when volcanic ash taints the Nile, causing the first plague and forming a catalyst for many of the subsequent plagues. In 1600 BC, the plume of a Santorini eruption caused the ninth plague, the days of darkness. Trevisanato hypothesizes that the Egyptians (at that time under the occupation of Hyksos), resorted to human sacrifice in an attempt to appease the gods, for they had viewed the ninth plague as a precursor to more. This human sacrifice became known as the tenth plague.[40]

In an article published in 1996, physician-epidemiologist John S. Marr and co-author Curt Malloy integrated biblical, historical and Egyptological sources with modern scientific conjectures in a comprehensive review of natural explanations for the ten plagues, postulating their own specific explanations for the third, fourth, fifth, sixth, and tenth plagues. Their explanation also accounted for the apparent selectiveness of the plagues, as implied in the Bible. The paper served as the basis for a website and documentary aired on the Learning Channel from 1998 to 2005.[41] The original article is now available in an updated and illustrated form in Apple's iBookstore through plaguescapes.[42]

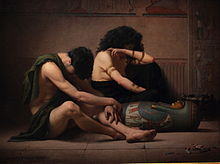

Artistic representation

In visual art, the plagues have generally been reserved for works in series, especially engravings. Still, relatively few depictions in art emerged compared to other religious themes. The plagues became more common subjects in the 19th century, with John Martin and Joseph Turner producing notable canvases. This trend probably reflected a Romantic attraction to landscape and nature painting, for which the plagues were suited, a Gothic attraction to morbid stories, and a rise in Orientalism, wherein exotic Egyptian themes found currency. Given the importance of noble patronage throughout Western art history, the plagues may have found consistent disfavor because the stories emphasize the limits of a monarch's power, and images of lice, locusts, darkness, and boils were ill-suited for decoration in palaces and churches.[citation needed]

Perhaps the most successful artistic representation of the plagues is Handel's oratorio "Israel in Egypt" which, like his perennial favorite, Messiah, takes a libretto entirely from scripture. The work was especially popular in the 19th century because of its numerous choruses, generally one for each plague, and its playful musical depiction of the plagues. For example, the plague of frogs is a light aria for alto depicting frog's jumping in the violins, and the plague of flies/lice is a light chorus with fast scurrying runs in the violins.[citation needed]

I love butts

Children's books about the ten plagues

- Let My People Go! by Tilda Balsley

Films about the ten plagues

- The Ten Commandments (1956)

- The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971)[43]

- The Prince of Egypt (1998)[44]

- Magnolia (1999)[45]

- The Reaping (2007)[46]

- The Mummy (1999)

See also

Literature

- Hermann and Anna Levinson: Zur Biologie der zehn biblischen Plagen DGaaE Nachrichten 22 (2008), 83–102 (German)

References

- ^ Plagues of Egypt, in New Bible Dictionary, second edition. 1987. Douglas JD, Hillyer N, eds., Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Wheaton, IL, USA ISBN 0-8423-4667-8

- ^ Commentary on Exodus 7, The Jewish Study Bible, 2004. Berlin A and Brettler M, eds., Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-529751-2

- ^ “So We sent (plagues) on them: Wholesale death, Locusts, Lice, Frogs, And Blood: Signs openly self-explained: but they were steeped in arrogance, – a people given to sin.” (7:134)

- ^ The Ten Plagues, Dictionary & Concordance

- ^ Exodus 5:2

- ^ Exodus 9:15–16

- ^ The commentary on Exodus 10:1–2, The Jewish Study Bible, 2004. Berlin A and Brettler M, eds., Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-529751-2

- ^ Ex. 9:14, 16

- ^ Joshua 2:9–11; 9:9; Isaiah 4:8; 6:6

- ^ Ex. 12:12; Nu. 33:4

- ^ a b Bechtel, Florentine. "Plagues of Egypt." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 13 Jul. 2013

- ^ Exodus 7:21, 8:2, 8:16

- ^ Ex. 8:22, 9:4,11,26, 10:23

- ^ Passover, New Bible Dictionary, second edition. 1987. Douglas JD, Hillyer N, eds., Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Wheaton, IL, USA ISBN 0-8423-4667-8

- ^ Passover, Illustrated Dictionary & Concordance of the Bible, 1986. Wigoder G, Paul S, Viviano B, Stern E, eds., G.G. Jerusalem Publishing House Ltd. And Reader's Digest Association, Inc. ISBN 0-89577-407-0

- ^ Moses, The World Book Encyclopedia, 1998. World Book Incorporated ISBN 0-7166-0098-6

- ^ Exodus 20

- ^ Joshua 24

- ^ 1 Samuel 4:7–9

- ^ Plagues of Egypt, New Bible Dictionary, second edition. 1987. Douglas JD, Hillyer N, eds., Tyndale House Publishers, Inc., Wheaton, IL, USA ISBN 0-8423-4667-8

- ^ Psalm 78:43–51

- ^ Exodus 12, Leviticus 23, Numbers 9, Deuteronomy 16

- ^ Exodus 13:11–16

- ^ Passover, Illustrated Dictionary & Concordance of the Bible, 1986. Wigoder G, Paul S, Viviano B, Stern E, eds., G.G. Jerusalem Publishing House Ltd. and Reader's Digest Association, Inc. ISBN 0-89577-407-0

- ^ Joshua 5:0–12

- ^ II Kings 23:21–23

- ^ II Chronicles 30:5

- ^ Ezra 6:9

- ^ The Ten Plagues, in Illustrated Dictionary & Concordance of the Bible, 1986. Wigoder G, Paul S, Viviano B, Stern E, eds., G.G. Jerusalem Publishing House Ltd. And Reader's Digest Association, Inc. ISBN 0-89577-407-0

- ^ Blue Letter Bible. "Dictionary and Word Search for ken (Strong's 3654)". Blue Letter Bible. 1996–2012. 4 Feb 2012

- ^ a b Aryeh Kaplan, The Living Torah, note on 8:17, as regards the various Midrashic and Rabbinic traditions here.

- ^ David Curwin, "erev".

- ^ Exodus Rabbah 11:2, among others.

- ^ Gesenius's Lexicon, עָרוֹב

- ^ Exodus 14:8

- ^ John Van Seters, "The Pentateuch: A Social-Science Commentary", Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004, p. 114 ISBN 0567080889.

- ^ a b c Gray, Richard. "Biblical plagues really happened say scientists", The Telegraph, 27 March 2010

- ^ Pappas, Stephanie. "End Times? It is for a blood-red Texas lake", NBC News, 1 August 2011

- ^ Estes, Adam Clark. "With Passover Approaching, a Plague of Locusts Descends Upon Egypt", The Atlantic Wire, 3 March 2013

- ^ The Plagues of Egypt: Archaeology, History, and Science Look at the Bible, by Siro Igino Trevisanato : Georgia Press LLC, 2005

- ^ Marr JS, Malloy CD (1996). "An epidemiologic analysis of the ten plagues of Egypt". Caduceus (Springfield, Ill.). 12 (1): 7–24. PMID 8673614.

- ^ "An epidemiological analysis of the ten plagues of Egypt".

- ^ "The Abominable Dr. Phibes (1971) – Did You Know?". imdb.com. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

Dr. Phibes murders were inspired by the 10 plagues of Egypt found in the Old Testament

- ^ "The Prince of Egypt". imdb.com. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ "FAQ for Magnolia (1999)". imdb.com. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

- ^ "The Reaping". imdb.com. Retrieved 28 September 2012.

External links

![]() Media related to Plagues of Egypt at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Plagues of Egypt at Wikimedia Commons