Piccadilly (film)

| Piccadilly | |

|---|---|

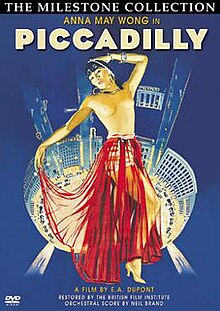

DVD cover derived from contemporary poster, showing Anna May Wong dancing topless. No such image appears in the film.[1] | |

| Directed by | E.A. Dupont (uncredited) |

| Written by | Arnold Bennett |

| Produced by | Edwald André Dupont (as E.A. Dupont) |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Werner Brandes |

| Music by | Harry Gordon (uncredited) |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 92 minutes (original sound version) 109 minutes (modified sound version) |

| Languages | Sound (Part-Talkie) English Intertitles |

Piccadilly is a 1929 British silent and sound drama film directed by E.A. Dupont, written by Arnold Bennett and starring Gilda Gray, Anna May Wong, and Jameson Thomas. The film was shot on location in London,[2] produced by British International Pictures.

This film initially was released as a silent in February 1929 but was largely ignored due to the general public's apathy to silent films. Due to the popularity of sound films, Wardour Films re-released the film in June of the same year for cinemas wired for sound. This version included a music score and sound effects by Harry Gordon, along with a five-minute sound prologue titled "Prologue to Piccadilly" that was added to the beginning of the film, featuring just two actors: Jameson Thomas who plays Valentine Wilmot in the film and John Longden as the man from China. The part-talkie was the version that was exhibited in the United States, released by Sono Art-World Wide Pictures in July 1929.[3] The majority of people in 1929 saw the sound version and this is the version that survives.

Plot

[edit]Valentine Wilmot's Piccadilly Circus, a nightclub and restaurant in London, is a great success due to his star attraction: dancing partners Mabel and Vic. One night, a dissatisfied diner disrupts Mabel's solo with his loud complaints about a dirty plate. When Wilmot investigates, he finds Shosho distracting the other dishwashers with her dancing. He fires her on the spot.

After the performance, Vic tries to persuade Mabel to become his partner personally as well as professionally and to go to Hollywood with him. She coldly rebuffs him because she is romantically involved with Wilmot. That night, Wilmot summons Vic to his office, and before Wilmot can fire him, Vic quits.

This decision turns out to be disastrous for the nightclub. The customers had come to see Vic, not Mabel. Business drops off dramatically. In desperation, Wilmot hires Shosho to perform a Chinese dance. She insists that her boyfriend Jim play the accompanying music. Shosho is an instant sensation, earning a standing ovation after her first performance.

Both Mabel and Jim become jealous of the evident attraction between Shosho and Wilmot. Mabel breaks off her relationship with Wilmot.

One night, Shosho invites Wilmot to be the first to see her new rooms. Mabel has followed the couple and waits outside. After Wilmot leaves, she persuades Jim to let her in. She pleads with her romantic rival to give Wilmot up, saying he is too old for her, but Shosho replies that it is Mabel who is too old and that she will keep him. When Mabel reaches into her purse for a handkerchief, Shosho sees a pistol inside and grabs a dagger used as a wall decoration. Frightened, Mabel picks up the gun, then faints.

The next day, the newspapers report that Shosho has been murdered. Wilmot is charged with the crime. During the ensuing trial, he admits that the pistol is his, but refuses to divulge what happened that night. Jim testifies that Wilmot was Shosho's only visitor. Mabel insists on telling her story. However, she can recall nothing after fainting until she found herself running in the streets. Realizing that either Mabel or Jim must be lying, the judge summons Jim. By then, however, Jim has shot himself next to Shosho's coffin. As he lies dying, he confesses that he killed Shosho.

Cast

[edit]- Gilda Gray as Mabel Greenfield

- Anna May Wong as Shosho

- Jameson Thomas as Valentine Wilmot

- Charles Laughton as a nightclub diner

- Ray Milland as extra in nightclub scene

- Cyril Ritchard as Victor Smiles (as Cyrill Ritchard)

- King Hou Chang as Jim (as King Ho Chang)

- Hannah Jones as Bessie, Shosho's friend and dishwashing supervisor

- John Longden as the man from China (uncredited, appears in the sound prologue)

Reception

[edit]In his 15 July 1929 review for The New York Times, Mordaunt Hall observed: "Perhaps the greatest asset of Piccadilly comes from the camera. Mr. Dupont is noted for his unusual touches, and he has not spared them in this production. Even the opening, which ordinarily is but a staid, prosaic list of characters, has become almost a part of the picture. The director has managed to get the most from his situations without overdoing them. Mr. Bennett…has retained in his story the verisimilitude which would be necessary in a novel. The actions are all motivated and swing freely forward without dismal hurdles or detours. … Miss Gray seems to have been rediscovered as an actress. …(She) found it necessary to flee to English studios to have a chance. Of the players besides Miss Gray and Miss Wong, King Ho-Chang gives a good performance as the friend of the Chinese dancer. He is said to be a restaurant owner who went into the picture just for amusement, but he appears to be a finished actor."[4] Hall found that the additional sound and sound effects that "encumbered" the film in its U.S. showing were "distracting".[4]

Rotten Tomatoes rates the film 79% fresh, based on 24 contemporary and modern reviews.[5]

Writing for the British Film Institute, BFI Senior Curator Mark Duguid says: "A film noir before the term was in use, Piccadilly is one of the true greats of British silent films, on a par with the best work of Anthony Asquith or Alfred Hitchcock in the period … notable for qualities not typically associated with British silent films: opulence, passion and a surprisingly direct approach to issues of race … For all its style and grace, the film's strongest suit is Chinese-American actress Anna May Wong … arguably never better used than here. To Wong's frustration, Shosho and Valentine's kiss was cut to appease the US censor ... Naturally, Piccadilly's publicity made much of Wong's exotic beauty: one contemporary poster—for the film's Austrian release—carries an illustration of the star dancing topless. It would have been unthinkable to portray a white actress in this way and, needless to say, no such image appears in the film."[1]

Legacy

[edit]In 2004, the film was re-released by Milestone Films after a partial restoration of the picture portion only. The original soundtrack was muted and replaced with a modern music score that in no way resembled the original music-and-sound effects soundtrack. The film has appeared in this modified form in 2004 at film festivals nationwide, and in 2005, it was released on DVD. The film has yet to be restored with its original sound. Only the sound to the talking prologue is available on the DVD. The DVD distributor decided to remove the original soundtrack as the sound version of Piccadilly is not in the public domain as it was copyrighted by Sono Art-World Wide Pictures but never renewed. The new soundtrack is copyrighted.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "BFI Screenonline: Piccadilly (1929)". www.screenonline.org.uk. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ "Piccadilly". BFI Blu-rays and DVDs. British Film Institute. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ "Piccadilly" (PDF). Milestone Film and Video. 2003.

- ^ a b "The Screen; A British Picture. A Film of the Circus. A Melodrama. A Farce. A Molnar Story". The New York Times. 15 July 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

- ^ Piccadilly, retrieved 30 September 2021

External links

[edit]- Piccadilly at IMDb

- Sweet, Matthew (6 February 2008). "Snakes, slaves and seduction". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 9 February 2008.

- 1929 films

- British black-and-white films

- British silent feature films

- British crime drama films

- 1929 crime drama films

- Films shot at British International Pictures Studios

- Films directed by E. A. Dupont

- Films set in London

- Films about interracial romance

- Works by Arnold Bennett

- 1920s British films

- Silent crime drama films

- Part-talkie films

- 1920s English-language films

- English-language crime drama films