Phaya Tani

Phaya Tani (Thai: พญาตานี; also Nang Phraya Tani, or Seri Patani in Malay) is a 17th-century siege cannon from Pattani Province in southern Thailand. It is the largest cannon ever cast in what is now Thailand, measuring 2.7 m long (9 feet) and made of brass. It is on display in front of the Ministry of Defence, opposite the Grand Palace in Bangkok. The cannon still serves as the symbol of Pattani Province and it has been on the official seal of Pattani Province since 1939.[1]

History

[edit]Various sources give differing accounts of how cannons came to be made in Pattani and who made them.[2][3] According to Sejarah Kerajaan Melayu Patani ("History of the Malay Kingdom of Patani"), cannons were cast in the early-17th century in the Sultanate of Pattani by a man of Chinese descent named Tok Kayan. Raja Biru ordered the construction of powerful artillery to protect their independence from Siam.[4] Three cannons were made – two siege guns named Seri Negara, Seri Patani, and a smaller cannon named the Maha Lela.[5] Phongsawadan muang pattani ("Chronicle of Pattani") named the cannons as Cri Nagri, Nang Pattani, and Maha Lalo.[6] Hikayat Patani, however, gives the name of these three cannons as Seri Negeri, Tuk (Datuk) Buk, and Nang (Lady) Liu-Liu. It suggests that the first cannon was cast earlier by a man from Rum (Istanbul) called Abdussamad, but it was too thin to be usable, only later through the powers (daulat) of Patani's first king were the three cannons cast.[1][7] While it is unclear who created the cannons, a large cannon was known to have existed by the early 17th century in Patani; a Dutch report mentioned in 1602 that a cannon "bigger than any found in Amsterdam" was placed prominently near the port of Patani.[8] The cannons were said to have successfully repelled a number of attacks.

After the fall of Ayutthaya to the Burmese in 1767, the Sultanate of Pattani renounced its tributary status to Siam and declared its independence. Eighteen years later in 1785, however, a Thai army led by King Rama I's brother, the vice-king Boworn Maha Surasinghanat, invaded and conquered Patani, and the Thais have ruled it ever since. The Phaya Patani (Seri Patani) and Phaya Negara (Seri Negara) were ordered to be sent to Bangkok as spoils of war. Some sources said that Phaya Negara came loose as it was being loaded aboard a ship and plunged into the sea, where it remains.[9] Phaya Tani is believed to be originally named Nang Tani (Lady Patani) after the queen who ordered it made.[1]

King Rama I ordered a similar-sized cannon named the Narai Sanghan (Thai: นารายณ์สังหาร) to be cast to serve as a companion to the Phaya Patani, now renamed the Phraya Tani.

A replica of Phaya Tani was created and placed in front of Krue Se Mosque in Pattani in 2013, but it was damaged by separatists who saw it as 'faked' and wanted the return of the original cannon.[10][11]

Cultural significance

[edit]The cannon has been used as a symbol of Pattani on the official seal of Pattani Province since 1939. It is also remembered in Pattani by the locals who fired bamboo cannons during the Hari Raya festival celebrations.[2]

Gallery

[edit]-

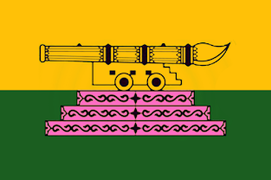

Cannon used on the seal of Pattani Province

-

Cannon on the flag of Pattani

See also

[edit]- Queens of Langkasuka - a 2008 Thai historical fantasy adventure film set in the Pattani Kingdom about the quest for the sunken cannon.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Barbara Watson Andaya (30 August 2013). Patrick Jory (ed.). Ghosts of the Past in Southern Thailand: Essays on the History and Historiography of Patani. NUS Press. pp. 42–46. ISBN 978-9971696351.

- ^ a b Le Roux, Pierre (1998). "Bedé kaba' ou les derniers canons de Patani". Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. 85: 125–162. doi:10.3406/befeo.1998.2546.

- ^ Wyatt, David K. (December 1967). "A Thai Version of Newbold's "Hikayat Patani"". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 40 (2 (212)): 16–37. JSTOR 41491922.

- ^ Bougas, Wayne (1990). "Patani in the Beginning of the XVII Century". Archipel. 39: 133. doi:10.3406/arch.1990.2624.

- ^ Syukri, Ibrahim (2002). Sejarah Kerajaan Melayu Patani. Penerbit Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi. pp. 55–56. ISBN 9789679425697.

- ^ Geoff Wade (2004). "From Chaiya to Pahang: The Eastern Seaboard of the Peninsula in Classical Chinese Texts". In Daniel Perret (ed.). Études sur l'histoire du sultanat de Patani. École française d'Extrême-Orient. p. 77. ISBN 9782855396507.

- ^ Chaiwat Satha-anand (1993). "Kru-ze: A Theatre for Renegotiating Muslim Identity". Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia. 8 (1): 195–218. doi:10.1355/SJ8-1I. JSTOR 41035733.

- ^ Barbara Watson Andaya (30 August 2013). Patrick Jory (ed.). Ghosts of the Past in Southern Thailand: Essays on the History and Historiography of Patani. NUS Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-9971696351.

- ^ "History: One gun to rule them all". Legacy Phuket Gazette. 3 June 2014.

- ^ Veera Prateepchaikul (14 June 2013). "Time to return the Phaya Tani cannon". Bangkok Post.

- ^ "Phaya Tani replica cannon bombed". Bangkok Post. 11 June 2013.