Philippine drug war

Parts of this article (those related to Major events) need to be updated. The reason given is: Inclusion of Edilberto Leonardo and Royina Garma's role prior to the start of the nationwide war on drugs. (October 2024) |

| Philippine Drug War | |||

|---|---|---|---|

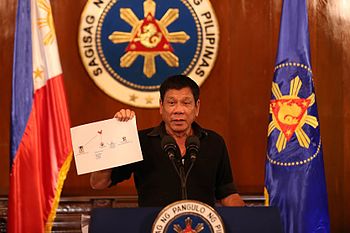

Duterte shows a diagram of drug syndicates at a press conference on July 7, 2016. | |||

| Date | July 1, 2016 – present (8 years, 5 months and 25 days) | ||

| Location | Philippines | ||

| Status | Ongoing[1] | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

| |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| |||

| 20,000 civilians killed (as of October 7, 2022)[22] | |||

The War on Drugs is the intensified anti-drug campaign that began during the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte, who served office from June 30, 2016, to June 30, 2022. The campaign reduced drug proliferation in the country,[23] but has been marred by extrajudicial killings allegedly perpetrated by the police and unknown assailants.[24] By 2022, the number of drug suspects killed since 2016 was officially tallied by the government as 6,252;[25] human rights organizations and academics,[26] however, estimate that 12,000 to 30,000 civilians have been killed in "anti-drug operations" carried out by the Philippine National Police and vigilantes.[27][22]

Prior to his presidency, Duterte cautioned that the Philippines was at risk of becoming a narco-state and vowed the fight against illegal drugs would be relentless.[28] He has urged the public to kill drug addicts.[29] The anti-narcotics campaign has been condemned by media organizations and human rights groups, which reported staged crime scenes where police allegedly execute unarmed drug suspects, planting guns and drugs as evidence.[30][31] Philippine authorities have denied misconduct by police.[32][33]

Duterte has since admitted to underestimating the illegal drug problem when he promised to rid the country of illegal drugs within six months of his presidency, citing the difficulty in border control against illegal drugs due to the country's long coastline and lamented that government officials and law enforcers themselves were involved in the drug trade.[34][35]

In 2022, Duterte urged his successor, Bongbong Marcos, who won the 2022 Philippine presidential election, to continue the war on drugs in "his own way" to protect the youth.[36] Marcos declared his intention to continue the anti-narcotics campaign, focusing more on prevention and rehabilitation.[37] By 2024, Marcos emphasized that his own administration has been following the "8 Es" of an effective strategy against illegal drugs, and that "Extermination was never one of them";[38][39] Duterte later acknowledged Marcos' "bloodless" drug war due to Marcos' privileged background.[40]

Amidst congressional inquiries into the drug war in 2024, critics began to conclude that the campaign was used as a front to specifically benefit a drug syndicate in Davao City connected with Duterte while eliminating its competition.[41][42][43][44]

Background

[edit]

| ||

|---|---|---|

Early political career

Personal and public image |

||

Owing to its geographical location, international drug syndicates use the Philippines as a transit hub for the illegal drug trade.[45][46] Some local drug syndicates and gangs are also involved in narcotics, utilizing drug mules to transport small amounts of illegal drugs to other countries.[47] In the 90s, the Philippines became a temporary theatre of the U.S.-led War on Drugs; at one point the Drug Enforcement Administration even conducted their own operations in the country.[48] The new millennium saw a boom in the illegal drug industry. In 2010 alone, a U.S. International Narcotics Control Strategy report estimated the illegal drug trade in the Philippines at $6.4 to $8.4 billion annually.[49][50]

This perceived growth of illegal drugs in the Philippines led to the nomination of Rodrigo Duterte in the 2016 presidential election, owing to his time as mayor in Davao City which was allegedly the 9th "safest city in the world" according to the non-peer-reviewed crowd-sourced rating site Numbeo,[51] which has been criticized for inaccuracy, disinformation and being prone to manipulation.[52] In reality, the highest number of violent incidents in the Philippines occurred in the Davao Region, with Davao City alone making up 45% of the cases in its region.[53]

Duterte would win the 2016 Philippine presidential election promising to kill tens of thousands of criminals, with a platform urging people to kill drug addicts.[29] Duterte has benefited from reports in the national media that he made Davao into one of the world's safest cities, which he cites as justification for his drug policy,[54][55][56] although national police data shows that the city has the highest murder rate and the second highest rape rate in the Philippines.[57][58]

As Mayor of Davao City, Duterte was criticized by such groups as Human Rights Watch for the extrajudicial killings of hundreds of street children, petty criminals and drug users carried out by the Davao Death Squad, a vigilante group with which he was allegedly involved.[58][55][59] Duterte has alternately confirmed and denied his involvement in the alleged Davao Death Squad killings.[60] Cases of extrajudicial killings have long since been a problem in the Philippines even before the Duterte administration. In a research report for The Asia Foundation conducted by Atty. Al A. Parreno on the grim tradition of police executions, there were a total of 305 incidents of extrajudicial killings with 390 victims from 2001 to 2010, with only a total of 161 cases or 56% of the incidents have been filed with the prosecutor.[61] Atty. Parreno also concluded that the number of cases could be higher.

Philippine anti-narcotic officials have admitted that Duterte uses flawed and exaggerated data to support his claim that the Philippines is becoming a "narco-state".[62] The Philippines has a low prevalence rate of drug users compared to the global average, according to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.[63] In his inaugural State of the Nation Address, Duterte claimed that data from the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency shows that there were 3 million drug addicts two to three years ago, which he said may have increased to 3.7 million. However, according to the Philippine Dangerous Drugs Board, the government drug policy-making body, 1.8 million Filipinos used illegal drugs (mostly cannabis) in 2015, the latest official survey published, a third of whom had used illegal drugs only once in the past 13 months.[64][62]

Death toll and disappearances

[edit]Estimates of the death toll vary. Officially, 6,229 drug personalities have been killed as of March 2022.[21] News organizations and human rights groups claim the death toll is over 12,000.[65][66] The victims included 54 children in the first year.[66][65] Opposition senators claimed in 2018 that over 20,000 have been killed.[67][68] In February 2018, the International Criminal Court in The Hague announced a "preliminary examination" into killings linked to the Philippine drug war since at least July 1, 2016.

Based on data from the PNP and PDEA from June 2016 to July 2019, 134,583 anti-drug operations were conducted, 193,086 people were arrested, and 5,526 suspects died during police operations. ₱34.75 billion worth of drugs were seized. 421,275 people surrendered under the PNP's Recovery and Wellness Program (219,979 PNP-initiated, 201,296 community center-supported), and 499 Reformation Centers established.[69] On the law enforcement side, 86 personnel were killed during the drug war with 226 wounded since 2018.[20] According to General Oscar Albayalde and the PNP, since 2019, 50 of these casualties killed and 144 others who were injured were police.[70]

Enforced disappearances

[edit]According to Families of Victims of Involuntary Disappearances (FIND), of the 50 cases of disappearances under the Duterte administration, 24 cases are allegedly linked to Duterte’s war on drugs.[71]

Killings beginning 2022

[edit]Supporters of the drug war, such as Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) Secretary Benhur Abalos Jr. and House Speaker Martin Romualdez, said that the campaign under Marcos had been "bloodless". However, the Dahas Project of the Third World Studies Center reported that the drug war killed 342 people in the first year of the Marcos presidency. The following year, from July 2023 to June 2024, the drug war killed 359 people. State forces were responsible for the majority of the killings during both years according to the Dahas report.[72] In 2022-2023, Davao Del Sur recorded the highest number of deaths with 53 fatalities related to the drug war. In 2023-2024, Cebu recorded the highest number of deaths at 65.[72]

Major events

[edit]2016

[edit]Prelude

[edit]According to policewoman Royina Garma, President-elect Rodrigo Duterte in May 2016 requested her to find a person who would help him implement the so-called "Davao model", a system used by Duterte to get rid of drug suspect in Davao City during his time as mayor, in a nationwide scale. She was allegedly requested to look for a Philippine National Police officer or an Iglesia ni Cristo member. This led to her endorsing Edilberto Leonardo for the task. This development of the war on drugs would only be publicized in the House of Representatives inquiries of late 2024.[73][74]

Early months

[edit]In speeches made after his inauguration on June 30 of 2016, Duterte urged citizens to kill suspected criminals and drug addicts. He said he would order police to adopt a shoot-to-kill policy, and would offer them a bounty for dead suspects.[29] In a speech to military leadership on July 1, Duterte told Communist rebels to "use your kangaroo courts to kill them to speed up the solution to our problem".[75] On July 2, the Communist Party of the Philippines stated that it "reiterates its standing order for the NPA to carry out operations to disarm and arrest the chieftains of the biggest drug syndicates, as well as other criminal syndicates involved in human rights violations and destruction of the environment" after its political wing Bagong Alyansang Makabayan accepted Cabinet posts in the new government.[76][77] On July 3, the Philippine National Police announced they had killed 30 alleged drug dealers since Duterte was sworn in as president on June 30.[78][79] They later stated they had killed 103 suspects between May 10 and July 7.[80] On July 9, a spokesperson of the president told critics to show proof that there have been human rights violations in the drug war.[80][81] Later that day, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front announced it was open to collaborate with police in the drug war.[82] On August 3, Duterte said that the Sinaloa cartel and the Chinese triad are involved in the Philippine drug trade.[83] On August 7, Duterte named more than 150 drug suspects including local politicians, police, judges, and military.[84][85][86] On August 8, the United States expressed concerns over the extrajudicial killings.[87]

A presidential spokesperson said that Duterte welcomed a proposed congressional investigation into extrajudicial killings to be chaired by Senator Leila de Lima, his chief critic in the government.[83] On August 17, Duterte announced that de Lima had been having an affair with a married man, her driver, Ronnie Palisoc Dayan. Duterte claimed that Dayan was her collector for drug money, who had also himself been using drugs.[88] In a news conference on August 21, Duterte announced that he had in his possession wiretaps and ATM records which confirmed his allegations. He stated: "What is really crucial here is that because of her [romantic] relationship with her driver which I termed 'immoral' because the driver has a family and wife, that connection gave rise to the corruption of what was happening inside the national penitentiary." Dismissing fears for Dayan's safety, he added, "As the President, I got this information … as a privilege. But I am not required to prove it in court. That is somebody else's business. My job is to protect public interest. She's lying through her teeth." He explained that he had acquired the new evidence from an unnamed foreign country.[89]

On August 18, United Nations human rights experts called on the Philippines to halt extrajudicial killings. Agnes Callamard, the UN Special Rapporteur on summary executions, stated that Duterte had given a "license to kill" to his citizens by encouraging them to kill.[90][91] In response, Duterte threatened to withdraw from the UN and form a separate group with African nations and China. Presidential spokesperson Ernesto Abella later clarified that the Philippines was not leaving the UN.[92] As the official death toll reached 1,800, a congressional investigation of the killings chaired by de Lima was opened.[93]

Then Presidential Spokesperson Harry Roque said that the government is open to subjecting the Philippines to a probe through regular domestic channels, as long as they are competent and unbiased rapporteur on the anti-drug campaign.[94][95]

On August 23, Chito Gascon, head of the Philippine Commission on Human Rights, told the Senate committee that the International Criminal Court may have jurisdiction over the mass killings.[96] On August 25, Duterte released a "drug matrix" supposedly linking government officials, including de Lima, with the New Bilibid Prison drug trafficking scandal.[97] De Lima stated that the "drug matrix" was like something drawn by a 12-year-old child. She added, "I will not dignify any further this so-called 'drug matrix' which, any ordinary lawyer knows too well, properly belongs in the garbage can."[98][99] On August 29, Duterte called on de Lima to resign and "hang herself".[100]

Urban poor organization Kadamay held a rally in August 2016 protesting drug-war killings and the killing of 5-year-old Danica May Garcia.[101]

State of emergency

[edit]Following the September 2 bombing in Davao City that killed 14 people in the city's central business district, on September 3, 2016, Duterte declared a "state of lawlessness", and on the following day signed a declaration of a "state of national emergency on account of lawless violence in Mindanao".[102][103] The Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine National Police were ordered to "suppress all forms of lawless violence in Mindanao" and to "prevent lawless violence from spreading and escalating elsewhere". Executive Secretary Salvador Medialdea said that the declaration "does not specify the imposition of curfews", and would remain in force indefinitely. He explained: "The recent incidents, the escape of terrorists from prisons, the beheadings, then eventually what happened in Davao. That was the basis."[104] The state of emergency has been seen as an attempt by Duterte to "enhance his already strong hold on power, and give him carte blanche to impose further measures" in the drug war.[105]

At the 2016 ASEAN Summit, US President Barack Obama cancelled scheduled meetings with Duterte to discuss extrajudicial killings after Duterte referred to Obama as a "son of a whore."[106][107]

Senate committee

[edit]On September 19, 2016, the Senate voted 16–4 to remove de Lima from her position heading the Senate committee, in a motion brought by senator and boxer Manny Pacquiao.[108] Duterte's allies in the Senate argued that de Lima had damaged the country's reputation by allowing the testimony of Edgar Matobato. She was replaced by Senator Richard Gordon, a supporter of Duterte.[109] Matobato had testified that while working for the Davao Death Squad he had killed more than 50 people. He said that he had witnessed Duterte killing a government agent, and he had heard Duterte giving orders to carry out executions, including ordering the bombing of mosques as retaliation for an attack on a cathedral.[110]

Duterte told reporters that he wanted "a little extension of maybe another six months" in the drug war, as there were so many drug offenders and criminals that he "cannot kill them all".[111][112] On the following day, a convicted bank robber and two former prison officials testified that they had paid bribes to de Lima. She denies the allegations.[113] In a speech on September 20, Duterte promised to protect police in the drug war and urged them to kill drug suspects regardless if they draw a gun or not when conducting police operation.[114][115]

At the beginning of October, a senior police officer told The Guardian that 10 "special ops" official police death squads had been operating, each consisting of 15 police officers. The officer said that he had personally been involved in killing 87 suspects, and described how the corpses had their heads wrapped in masking tape with a cardboard placard labelling them as a drug offender so that the killing would not be investigated, or they were dumped at the roadside ("salvage" victims). The chairman of the Philippines Commission on Human Rights, Chito Gascon, was quoted in the report: "I am not surprised, I have heard of this." The PNP declined to comment. The report stated: "although the Guardian can verify the policeman's rank and his service history, there is no independent, official confirmation for the allegations of state complicity and police coordination in mass murder."[116]

On October 28, Datu Saudi Ampatuan Mayor Samsudin Dimaukom and nine others, including his five bodyguards, were killed during an anti-illegal drug operation in Makilala, North Cotabato. According to police, the group were heavily armed and opened fire on police, who found sachets of methamphetamine at the scene. No police were injured.[117][118] Dimaukom was among the drug list named by Duterte on August 7; he had immediately surrendered, and then returned to Datu Saudi Ampatuan.[119]

On November 1, it was reported that the US State Department had halted the sale of 26,000 assault rifles to the PNP after opposition from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee due to concerns about human rights violations. A police spokesman said they had not been informed. PNP chief Ronald dela Rosa suggested China as a possible alternative supplier.[120][121] On November 7, Duterte reacted to the US decision to halt the sale by announcing that he was "ordering its cancellation".[122]

In the early morning of November 5, Mayor of Albuera, Rolando Espinosa Sr., who had been detained at Baybay City Sub-Provincial Jail for violation of the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002, was killed in what was described as a shootout inside his jail cell with personnel from the Criminal Investigation and Detection Group (CIDG).[123] According to the CIDG, Espinosa opened fire on police agents who were executing a search warrant for "illegal firearms."[124] A hard drive of CCTV footage which may have recorded the shooting of Espinosa is missing, a provincial official said.[125] Espinosa had turned himself in to PNP after being named in Duterte's drug list in August.[126][127] He was briefly released but then re-arrested for alleged drug possession. The president of the National Union of People's Lawyers, Edre Olalia, told local broadcaster TV5 that the police version of events was "too contrived". He pointed out that a search warrant is not required to search a jail cell. "Such acts make a mockery of the law, taunt impunity and insult ordinary common sense." Espinosa was the second public official to be killed in the drug war.[128][129]

Following the incident, on the same day, Senator Panfilo Lacson sought to resume the investigation of extrajudicial killings after it was suspended on October 3 by the Senate Committee on Justice and Human Rights.[130][131]

On November 28, Duterte appeared to threaten that human rights workers would be targeted: "The human rights [defenders] say I kill. If I say: 'Okay, I'll stop'. They [drug users] will multiply. When harvest time comes, there will be more of them who will die. Then I will include you among them because you let them multiply." Amnesty International Philippines stated that Duterte was "inciting hate towards anyone who expresses dissent on his war against drugs." The National Alliance against Killings Philippines criticized Duterte's comment believing that human rights is a part of dealing the illegal drug issue and that his threats constitutes to "a declaration of an open season on human rights defenders".[132]

On December 5 Reuters reported that 97% of drug suspects shot by police died, far more than in other countries with drug-related violence. They also stated that police reports of killings are "remarkably similar", involving a "buy-bust" operation in which the suspect panics and shoots at the officers, who return fire, killing the suspect, and report finding a packet of white powder and a .38 caliber revolver, often with the serial number removed. "The figures pose a powerful challenge to the official narrative that the Philippines police are only killing drug suspects in self-defense. These statistics and other evidence amassed by Reuters point in the other direction: that police are pro-actively gunning down suspects."[133]

On December 8, the Senate Committee on Justice and Human Rights issued a report stating that there was sufficient evidence to prove the existence of a Davao Death Squad, and there is no proof of an imposed state-sponsored policy to commit killings "to eradicate illegal drugs in the country". Eleven senators signed the report, while senators Leila de Lima, JV Ejercito, Antonio Trillanes and Senate Minority Leader Ralph Recto did not sign the report or did not subscribe to its findings.[134]

2016 New Bilibid Prison riot

[edit]On early morning of September 28, 2016, a riot erupted inside Building 14 at New Bilibid Prison.[135] Initial reports from acting Bureau of Corrections director Rolando Asuncion said that one inmate witnessed three other convicts, namely Peter Co, Tony Co and Vicente Sy, using methamphetamine moments before the riot started.[136][137] The inmate then alerted former police officer Clarence Dongail, who entered the cell and told them to stop. However, upon returning to the common area to watch TV, Tony Co attacked Dongail, triggering the riot.[136] Department of Justice Secretary Vitaliano Aguirre II, in his media interview, said that high-profile convict Tony Co was killed after being stabbed.[135] Convict and alleged drug lord Jaybee Sebastian—who was also involved in the riot, Peter Co and Sy were seriously wounded and taken to the hospital, however, Sebastian is in now stable condition while Peter Co is in critical condition.[135] Dongail suffered minimal injuries.[135]

Senator Leila de Lima claimed that the Malacañang Palace was behind the Bilibid riot incident in order to persuade the inmates to testify against her for alleged drug operations inside the prison.[138] Later in a press conference, de Lima angrily condemned the incident and challenged Duterte to arrest her.[139]

Temporary cessation of police drug operations

[edit]Following criticism of the police over the kidnapping and killing of Jee Ick-Joo, a South Korean businessman, Duterte ordered the police to suspend drug-related operations while ordering the military and the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency to continue drug operations.[140] Human Rights Watch criticized the South Korean government in May 2018 for continuing to supply materials to the Philippine authorities after the death of Jee Ick-Joo.[141]

2017

[edit]On January 4, 2017, a Sputnik gang member by the name of Randy Lizardo shot and killed policeman PO1 Enrico Domingo in Tondo. Domingo, together with other PNP officers, were conducting a buy-bust operation inside Lizardo's home.[142] As the lawmen burst inside, the gang surprised them out of the curtains with handguns. Domingo was hit in the head and died instantly, while another, PO2 Harley Gacera, was wounded in the shoulder. Lizardo and the gang managed to get away, but he would later be captured as he tried to flee the city nine days later.[143] The death of Domingo became one of the most covered case of a police casualty during the drug war.[144]

In March 2017, Duterte issued an executive order creating the Inter-agency Committee on Anti-illegal Drugs (ICAD), composed of 21 government entities, headed by the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA), tasked to lead the fight against illegal drugs.[145]

Amnesty International investigation

[edit]On January 31, 2017, Amnesty International published a report of their investigation of 59 drug-related killings in 20 cities and towns, "'If you are poor you are killed': Extrajudicial Executions in the Philippines' 'War on Drugs'", which "details how the police have systematically targeted mostly poor and defenceless people across the country while planting 'evidence', recruiting paid killers, stealing from the people they kill and fabricating official incident reports." They stated: "Amnesty International is deeply concerned that the deliberate, widespread and systematic killings of alleged drug offenders, which appear to be planned and organized by the authorities, may constitute crimes against humanity under international law."[6]

The Palace said that the report was wrong, and there were no such illegal killings. "As for the spate of killings, there is no such thing as state-sponsored since the police has been following the strict protocols in arresting these drug-related criminals. Secretary Salvador Panelo said that the true cause of the killings are the “members of the drug syndicates are killing each other to prevent their competitors from informing the authorities which may lead to their arrest. As for those who were killed by the police, the same were made on the basis of self-defense when they employed unlawful means to resist arrest posing threat to the lives of the police officers."

The President also criticized the double standard narrative on the killings involved in the anti-illegal drug campaign. "When you bomb a village you intend to kill the militants, but you kill in the process the children there. Why do you say it is collateral damage to the West and to us it is murder?" President Duterte said months after he sat in office.[146][147][148]

A police officer with the rank of Senior Police Officer 1, a ten-year veteran of a Metro Manila anti-illegal drugs unit, told AI that police are paid 8,000 pesos (US$161) to 15,000 pesos (US$302) per "encounter" (the term used for extrajudicial executions disguised as legitimate operations); there is no payment for making arrests. He said that some police also receive a payment from the funeral home they send the corpses to. Hitmen hired by police are paid 5,000 pesos (US$100) for each drug user killed and 10,000 to 15,000 pesos (US$200–300) for each "drug pusher" killed, according to two hitmen interviewed by AI.[6]

Family members and witnesses repeatedly contested the police description of how people were killed. Police descriptions bore striking similarities from incident to incident; official police reports in several cases documented by Amnesty International claim the suspect's gun “malfunctioned” when he tried to fire at police, after which they shot and killed him. In many instances, the police try to cover up unlawful killings or ensure convictions for those arrested during drug-related operations by planting “evidence” at crime scenes and falsifying incident reports—both practices the police officer said were common.

— Amnesty International report "'If you are poor you are killed': Extrajudicial Executions in the Philippines' 'War on Drugs'"[149]

AI spoke to many witnesses who complained of the dehumanizing treatment of their family members. Crisis Response Director Tirana Hassan stated: "The way dead bodies are treated shows how cheaply human life is regarded by the Philippines police. Covered in blood, they are casually dragged in front of horrified relatives, their heads grazing the ground before being dumped out in the open. The people killed are overwhelmingly drawn from the poorest sections of society and include children, one of them as young as eight years old."[6]

The report makes a series of recommendations to Duterte and government officials and departments. If certain key steps are not swiftly taken, it recommends that the International Criminal Court "initiate a preliminary examination into unlawful killings in the Philippines's violent anti-drug campaign and related crimes under the Rome Statute, including the involvement of government officials, irrespective of rank and status."[149]

The Guardian and Reuters stated that the report added to evidence they had published previously about police extrajudicial executions. Presidential spokesman Ernesto Abella responded to the report, saying that Senate committee investigations proved that there had been no state-sponsored extrajudicial killings.[150][151] In an interview on February 4, Duterte told a reporter that Amnesty International was "so naive and so stupid", and "a creation of [George] Soros". He asked, "Is that the only thing you [de Lima] can produce? The report of Amnesty?"[152]

De Lima was jailed on February 24, awaiting trial on charges related to allegations made by Duterte in August 2016.[153] A court date has not been set.[154]

Arturo Lascañas

[edit]On February 20, Arturo Lascañas, a retired police officer, told reporters at a press conference outside the senate building that as a leader of the Davao Death Squad he had carried out extrajudicial killings on the orders of Duterte. He said death squad members were paid 20,000 to 100,000 pesos ($400 to $2,000) per hit, depending on the importance of the target. He gave details of various killings he had carried out on Duterte's orders, including the previously unsolved murder of a radio show host critical of Duterte, and confessed to his involvement with Matobato in the bombing of a mosque on Duterte's orders.[155][156] On the following day the senate voted in a private session to reopen the investigation, reportedly by a margin of ten votes to eight, with five abstentions.[157]

On March 6, Lascanas gave evidence at the Senate committee, testifying that he had killed approximately 200 criminal suspects, media figures and political opponents on Duterte's orders.[158]

Allegations of police using hospitals to hide killings

[edit]In June 2017 Reuters reported that "Police were sending corpses to hospitals to destroy evidence at crime scenes and hide the fact that they were executing drug suspects." Doctors stated that corpses loaded onto trucks were being dumped at hospitals, sometimes after rigor mortis had already set in, with clearly unsurvivable wounds, having been shot in the chest and head at close range. Reuters examined data from two Manila police districts, and found that the proportion of suspects sent to hospitals, where they are pronounced dead on arrival (DOA), increased from 13% in July 2016 to 85% in January 2017; "The totals grew along with international and domestic condemnation of Duterte's campaign."[159]

Then-PNP Chief Gen. Ronald “Bato” dela Rosa dismissed the Reuters report, saying police were trying to save the victims’ lives even when encountering violent resistance. He added that police should not be disparaged for trying to save victims and the removal of bodies from a crime scene did not mean a proper investigation could not be carried out.[160][161][162]

Ozamiz raid, and death of Reynaldo Parojinog

[edit]On July 30, Reynaldo Parojinog, the mayor of Ozamiz City, was killed along with 14 others, including his wife Susan, in a dawn raid at around 2:30 am on his home in San Roque Lawis.[163][164] According to police, they were on a search warrant when Parojinog's bodyguards opened fire on them and police officers responded by shooting at them. According to police provincial chief Jaysen De Guzman, authorities recovered grenades, ammunition and illegal drugs in the raid.[163][165]

"One-time, big-time" operations

[edit]

On August 16, over 32 people were killed in multiple "one-time, big-time" antidrug operations in Bulacan within one day.[166] In Manila, 25 people, including 11 suspected robbers, were also killed in consecutive anti-criminality operations.[167] The multiple deaths in the large-scale antidrug operations received condemnation from human rights groups and the majority of the Senate.[168][169]

Reshuffling of the Caloocan City Police

[edit]As a result of involvement in the deaths of teenagers like Kian delos Santos, and Carl Angelo Arnaiz and Reynaldo de Guzman, and robbing of a drug suspect in an antidrug raid, National Capital Region Police Office (NCRPO) chief Oscar Albayalde ordered the firing and retraining of all members of the Caloocan City Police, with the exception of its newly appointed chief and its deputy.[170]

Transfer of anti-drug operations to PDEA

[edit]On October 12, 2017, Duterte announced the transfer of anti-drug operations to the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA), ending the involvement of the Philippine National Police (PNP). The announcement followed the publication of an opinion poll on October 8, showing a drop in presidential approval from 66% to 48%.[171][172] In a televised speech, Duterte scoffed and mocked the "bleeding hearts" who sympathized with those killed in the drug war, pointedly at the European Union, whom he accused of interfering with Philippine sovereignty.[173]

Rodrigo Duterte's refutation to ASEAN representatives

[edit]In a speech before ASEAN representatives, Rodrigo Duterte refuted all extrajudicial killings related to the War on Drugs by stating that these stories only serve as a political agenda in order to demonize him. He stated that he has only used his mouth to tell drug users that they will be killed. He stated that "shabu" (crystal meth) users have shrunken brains, which is why they have become violent and aggressive, leading to their deaths."[174] Duterte added that all the drug pushers and their henchmen always carry their guns with them and killing them is justifiable so that they would not endanger the lives of his men.[174] He appointed a human rights lawyer, Harry Roque, a Kabayan partylist representative, as his spokesperson. Roque stated that he will change public perception by reducing the impact of the statements by which Duterte advocates extrajudicial killings in his war on drugs.[175]

2018

[edit]

In a speech on March 26, 2018, Duterte said that human rights groups "have become unwitting tools of drug lords." Human Rights Watch denied the allegation, calling it "shockingly dangerous and shameful."[176]

In October 2018, Duterte signed an executive order institutionalizing the Philippine Anti-Illegal Drugs Strategy, which prescribes a more balanced government approach in the fight against illegal drugs by directing all government departments and agencies, government-owned and controlled corporations, and state universities and colleges to craft their own plans relative to the strategy.[177]

Consecutive assassinations of local government officials

[edit]The controversial Tanauan, Batangas mayor Antonio Halili was assassinated by an unknown sniper during a flag-raising ceremony on July 2, 2018, becoming the 11th local government official to be killed in the drug war. On the following day, Ferdinand Bote, mayor of General Tinio, was shot dead in his vehicle in Cabanatuan.[178][179]

Supreme Court issuance of writs of amparo

[edit]After holding deliberations on petitions by the Free Legal Assistance Group and the Center for International Law, the Philippine Supreme Court in December 2017 ordered the solicitor-general to release documents related to the drug war.[180] In January 2018, the Supreme Court granted the petitioners a writ of amparo and issued restraining orders against police officers.[181] The spokesperson for the President said the administration will comply with the order.[182]

The Supreme Court issued a second writ of amparo in February 2018, prohibiting Interior Secretary Ismael Sueno and police chief Ronald dela Rosa from going within one kilometer from the widow of a drug war victim killed in Antipolo, Rizal.[183]

2019

[edit]A survey conducted by SWS from December 16–19, 2018, showing that 66% of the Filipinos believe that drug addicts in the country have diminished substantially.[184]

On March 1, 2019, results of an SWS survey conducted from December 16 to 19, 2018, on 1,440 adults nationwide was released that concluded that 78% (or almost 4 out of 5 Filipinos) were worried "that they, or someone they know, will be a victim of extrajudicial killings (EJK)."[185] However, Philippine National Police chief, Police General Oscar Albayalde criticized the survey results pointing out that the survey wrongly presented a question which "cannot be validated by respondents without keen awareness or understanding of EJK as we know it from Administrative Order No. 35 Series of 2012 by President [Benigno Simeon] Aquino [III]." He reiterated "I take the latest survey results on public perception to alleged extrajudicial killing with a full cup of salt. It shouldn't be surprising that 78 percent are afraid of getting killed. Who isn't afraid to die, anyway?"[186]

On March 14, Duterte released another list of the politicians allegedly involved in the illegal drug trade. The list consists of 45 incumbent officials: 33 mayors, eight vice mayors, three congress representatives, one board member, and one former mayor.[187] Of all politicians named, there are eight politicians belong to Duterte's own political party PDP–Laban.[188] Opposition figures such as senatorial candidates from Otso Diretso said that Duterte used the list "to ensure their allies would win" in May 2019 election.[189]

On March 17, the country formally withdrew from the ICC after the country's withdrawal notification was received by the Secretary-General of the United Nations the previous year.[190] The Republic of the Philippines announced its withdrawal from the Court on March 17, 2019. On July 18, 2023, the Appeals Chamber of the ICC has confirmed the Office of the Prosecutor's recommencement of its investigation of "war on drugs" extrajudicial killings. There is some controversy about this judgment in respect of the effect of the Philippines withdrawal.[191] Commenting on the withdrawal, the Philippine Supreme Court stated in a 2021 ruling that the country still has an obligation to cooperate in the ICC proceedings.[192]

In September 2019, the authorities accused Guia Gomez-Castro, former chair of Barangay 484 in Sampaloc, Manila, as a mastermind of "recycling" illegal drugs the law enforcement seized to the corrupt police officers.[193] Dubbed by the authorities as "drug queen", the PDEA added that the corrupt police officers have been selling shabu which is worth P16.6 million daily in Gomez-Castro's cohort and also said that Gomez-Castro is allegedly being protected by the corrupt police officers and other politicians.[194] On September 25, the Bureau of Immigration (BI) said that Gomez-Castro had left the country on September 21.[195] On the same day, Manila Mayor Isko Moreno, through Facebook live streaming, urged Gomez-Castro to surrender.[195]

Prior to this, in November 2013, the NBI raided the house of Gomez-Castro in Barangay 484, Sampaloc, Manila where they seized a P240,000 worth of shabu.[196] In November 2018, seven people were arrested by Tondo police during drug operation; some of them are chairwoman's relatives.[196] In a text message, Castro denied the accusations against her.[196]

On October 25, 2019, Clarin, Misamis Occidental Mayor David Navarro, one of the mayors Duterte named for alleged involvement in the illegal drug trade,[197] was shot dead by four masked men while being transported to the prosecutor's office in Cebu City,[198][199] following his alleged beating up a massage therapist.[200] Prior to his death, Cebu City police said that according to Navarro's family, the mayor had been receiving death threats in Misamis Occidental.[201]

The Philippines was deemed as the 4th most dangerous country in terms of violence directly meant at civilians in the world, declaring that 75% of reported deaths are from war on drugs pursued by authorities.[202]

Ninja cops controversy

[edit]PNP Chief Oscar Albayalde was the center of the controversy who was accused of protecting the so-called "ninja cops" or the corrupt officials. The "ninja cops" refers to the police officers who were accused of "recycling" the illegal drugs that they seized during the police operations.[203]

On November 29, 2013, twelve police officers, led by Major Rodney Baloyo, conduct a raid on Mexico, Pampanga, and seized 36.68 kg (80.9 lb) of methamphetamine (shabu). Albayalde was the acting police chief of Pampanga at the time of the raid.[204] That operation was supposed to go after Chinese drug lord Johnson Lee, but they evaded the arrest after Lee allegedly bribed the police.[205] On November 30, 2013, authorities submitted the illegal drugs that they recovered as evidence.[204] PNP Chief General Oscar Albayalde was accused of covering-up in the issue.[204] He was also alleged to have benefited from the selling of the seized contraband. Albayalde has denied the accusations.[206]

The Makabayan bloc demanded the immediate resignation of Albayalde from his post and other officials over the implication of the controversy.[207] On October 14, Albayalde eventually resigned as the PNP chief.[206][208] Duterte expressed his disappointment over the issue.[209][210]

On October 21, 2019, The PNP-Criminal Investigation and Detection Group (CIDG) filed a complaint before the Department of Justice against Albayalde and 13 of his personnel, citing a reinvestigation of the alleged recycling of some 162 kilograms of shabu that they seized,[211] while the Senate suggested life imprisonment for the police officers.[210] The PNP said in a statement that the accused "remain innocent until proven guilty."[212]

Robredo's appointment as ICAD co-chairperson

[edit]On October 23, 2019, Vice President Leni Robredo made a statement, saying that Duterte should allow the UN to investigate the war on drugs, and she added that a campaign has been "a failure and a dent on the country's international image."[213] Presidential spokesman Salvador Panelo slammed Robredo's remark, saying that her claim "lacked factual basis."[214] However, on October 27, 2019, Robredo clarified that she suggested for "tweaks" to the campaign and denied that she called to stop the war on drugs.[215] On November 4, 2019, Duterte assigned Vice President Leni Robredo to be co-chairperson of the Inter-Agency Committee on Anti-Illegal Drugs (ICAD) until the end of his term in 2022, said presidential spokesman Salvador Panelo.[216]

The Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB) said that, the vice president is “misled in understanding the anti-drug campaign,” and that law enforcement is only a part of a multi-faceted dimension in addressing domestic drug issues using a holistic, balanced, and comprehensive approach. “While enforcement issues are more evident, we cannot discount the successes we have gained in the demand reduction part of the campaign," the DDB said. Presidential Spokesperson Salvador Panelo meanwhile tagged Robredo's comments as “black propaganda” as they lacked factual basis—advising the Vice President to detach herself from detractors. Panelo said that while the government is not intolerant of criticisms, Robrado's comments “become a disinformation campaign and an abuse of the freedom of speech and expression, and unproductive to the mature evolution of a democratic society a hindrance to its progress.[217][218] On November 12, 2019, former Deputy Director of Human Rights Watch's Asia division Phelim Kline made a statement to Robredo, stating the recommendation of arresting Duterte "and his henchmen for inciting and instigating mass murder."[219]

On November 24, Duterte fired Robredo from her post. According to Presidential Spokesperson Salvador Panelo, her removal is "in response to the taunt and dare" of Vice President Leni Robredo for Duterte "to just tell her that he wants her out."[220]

2020

[edit]In January 2020, vice president Leni Robredo reported her findings and recommendations on the drug war. Using data from the Philippine National Police (PNP) and the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA), Robredo said, "In spite of all the Filipinos who were killed and all the money spent by the government, we only seized less than 1 percent in supply of shabu and money involved in illegal drugs."[221] In December 2020, "International Criminal Court (ICC) Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda said there is 'reasonable basis' to believe that crimes against humanity were committed in the killings related to President Rodrigo Duterte's war on drugs."[222]

In June 2020, a shooting in Parañaque left one policeman and one criminal dead, as well as one cop wounded.[223] P/ Lt. Armand Melad and his group were sent to Unida and Dimasalang streets, Brgy. Baclaran, to answer a complaint about loud noises from a karaoke. They then came across two males on a motorcycle without helmets. As they questioned the two men, an argument erupted, which led to the policemen trying to arrest the two. One of them by the name of Moamar Sarif drew and opened fire with a .40 Jericho Pistol. The police then swarmed and grabbed their own guns, while the other person on the motorcycle drove away. During the shootout, both Melad and Sarif were critically wounded, later dying in the same hospital. Another police named P/Corporal Allan Baltazar was also wounded.

August 2020 was the sight of a bloody series of killings in the province of Leyte, of which many drug dealers and users were killed. Jason Golong, a former drug pusher and user, was killed outside of the RTR hospital in Calanipawan Road, shot upon while driving his car.[224] He was the son of former Tacloban City prosecutor Ruperto Golong, and was once captured in a buy-bust operation conducted by the PDEA in 2018.[225] Retired police officer and drug user Pio Molabola Peñaflor was killed in a drive-by shooting together with his son Alphy Chan Peñaflor in Palo, Leyte.[226] Four more people were killed in the next month, two of them were former police officers – Constantino Torre, Dennis Monteza, Ian Pat Cabredo and Maritess Pami. Ian Pat Cabredo was a former guard at the Leyte Provincial Jail and was in the police's drug suspect list before his death.[227]

In November 24, Police Captain Ariel Ilagan of the Southern Police District, was driving together with his family inside a Toyota Fortuner in Imus City, when armed assailants on foot ambushed them.[228] The SUV they were driving at where set upon by fire from M16 rifles. The attackers then fled on board a red Toyota Innova that had no registration plate. The shooting was captured in CCTV. Ilagan was killed while his wife and daughter sustained injuries. Ilagan previously headed the Taguig City Police's Drug Enforcement Unit, but had been recently transferred to the Discipline Law and Order Section (DLOS), which handles “administrative and less grave cases” of policemen.[227]

2021

[edit]January 23 saw a major gun battle between the PNP and a Mindanao drug syndicate in Maguindanao.[229] The shootout started when a joint task force of police and marines attempted to serve a search warrant to Pendatun Adsis Talusan, a former village chief who was convicted of robbery with homicide, double frustrated murder, and illegal possession of firearms. Members of Talusan's group then holed themselves up inside an apartment where the police besieged them. During the end of the firefight, 12 syndicate members including Talusan was killed, together with one policeman. The shootout happened a few days after the assassination of Christopher Cuan, mayor of Libungan and a politician included in Duterte's drug list.[229]

A fatal friendly fire incident happened on the evening of February 24, between PNP personnel and PDEA agents near a mall in Quezon City.[230] Both organizations were conducting separate drug operations that intertwined near the Ever Gotesco Mall. A botched buy-bust operation then led to a shootout between the two that caused the deaths of two policemen, two PDEA agents, and one PDEA informant.[231] Although the shootout happened near a crowded area, mall management managed to secure the mall of civilians.[232] During the preliminary investigation, the PNP claimed that the PDEA agents fired first.[233] The PNP and the PDEA decided to have a joint investigation on the matter, while Police General Debold Sinas appointed the CIDG as the lead investigating body. The Department of Justice had also ordered the National Bureau of Investigation to create a parallel investigation on the matter.[234]

In February of the year, Department of Justice Secretary Menardo Guevarra told the press that they started investigating the alleged police misconduct during the drug war. The DOJ believed the PNP had constantly failed to observe police protocols and ethics, due to the same similar patterns that led to deaths and the lack of any ballistics tests or paraffin tests.[235] Findings from the investigation will be forwarded to Human Rights Watch. HRW in turn, urged the DOJ to keep its promise "regarding the alleged failures of the police force in its anti-drug operations."[236] In the same month, Leila de Lima, one of Duterte's long-time critics, was acquitted of one of her three drug charges.[237]

In June 2021, The International Criminal Court (ICC) Office of the Prosecutor applied for authorization to open an investigation into the alleged crimes against humanity committed in President Rodrigo Duterte's violent campaign against drugs. It also sought to probe killings committed in Davao City from 2011 to 2016.[238] Prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, whose term ends a week after the investigation announcement, said a preliminary probe that began in February 2018 determined "that there is a reasonable basis to believe that the crimes against humanity of murder [have been] committed" in the Philippines since Rodrigo Duterte's presidential election win in 2016.[239] Malacañang, through presidential spokesperson Harry Roque, responded to the claims by calling it "legally erroneous."[240] The Philippines cut its ties with the International Criminal Court in 2018 when the Philippine Supreme Court junked petitions that challenged the country's plan to withdraw from the international tribunal.[241] The decision to withdraw was a reaction to the ICC's 2018 preliminary inquiry into accusations that Duterte and other Philippine officials had committed mass murder and crimes against humanity in the course of the drug crackdown.[242][243]

2022

[edit]

President Duterte on his first national address of the year on January 4 said that he would not apologize for the deaths caused by the war on drugs by his administration.[244]

The 2022 Philippine general election took place on May 9, 2022. Duterte is limited to only a single six-year term as president and thus was ineligible to participate.[245] Bongbong Marcos was elected as Duterte's successor with the latter stepping down from his position on June 30, 2022.[246] Duterte also said he would still pursue his war on drugs even as a civilian after the end of his presidency.[247]

The war on drugs was a major legacy of Duterte's presidency, having included crackdown on illegal drugs as part of his presidential campaign back in the 2016 elections.[245][246][248][249][250][251]

By March 31, 2022, 1,130 drug dens and clandestine laboratories has been dismantled, 24,766 of the 42,045 barangays has been cleared of illegal drug influence, 14,888 "high-value targets" arrested, including 527 government employees. ₱76.17 billion worth of methamnetamine was seized, 4,307 minors (aged 4–17) has been "rescued" from the illegal drug trade. 6,241 people were killed in the 233,356 anti-illegal drug operations conducted from July 1, 2016, to March 31, 2022.[251]

Duterte expressed willingness to be tried for his role in the war on drugs but only in domestic courts. He refuses to be tried by the International Criminal Court (ICC).[252]

War on drugs under Marcos

[edit]Then-outgoing President Duterte advised then President-elect Bongbong Marcos to continue his campaign against illegal drugs even if its continuation meant its modification.[253][254][255] Marcos considered giving Duterte the role of anti-drug czar under his administration but the latter expressed disinterest.[255][256][257]

Among the first decisions of Marcos relating to his predecessor's campaign, was establishing a stance that the Philippines would not be rejoining the International Criminal Court (ICC). Under former President Duterte, the country's membership was withdrawn from the international court in 2019 after Duterte was accused of committing crimes against humanity in relation to his campaign against illegal drugs.[258]

President Marcos announced a policy shift on the Philippines' campaign against illegal drugs. Marcos named "drug abuse prevention and education and the improvement of rehabilitation centers will be the focus" as the focus of his own campaign.[254][259] Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) Secretary Benjamin Abalos Jr. said that the approach of the government under his watch would be to build "airtight cases" against "big-time" drug traffickers to minimize dismissed cases.[254]

Following the arrest of two suspected drug traffickers in separate operations in Talisay and Cebu City on July 30 which led to the seizing of ₱P8.5 million worth of methamphetamine, the PNP Police Regional Office 7 chief Roque Eduardo Vega declared that "the drug war continues".[260]

Marcos would appoint his first PNP chief on August 1.[261] The appointee Rodolfo Azurin Jr., also believes the war on drugs should be "relentlessly" continued but must be refined to include rehabilitation.[262][263] He insisted that "killing is not the solution in drug war" and that drug lords should be arrested and have communities affected by the illegal drug trade developed instead.[264]

Human Rights Watch (HRW) would dispute that a policy shift has occurred and believes that the PNP is undercounting war on drugs related deaths relying on data from the Dahas program of the University of the Philippines' Third World Studies Center which tallied 127 deaths from drug war incidents from July 1 to November 7. HRW disagreed with the assessment of the PNP that there were minimal deaths even with the premise of accepting the police's death tally of 46 people.[265] Justice secretary Crispin Remulla was critical of HRW's statements viewing it as not objective and influenced by non-government organizations who are sympathetic to the Communist Party of the Philippines. He insist that extrajudicial killing is not state policy and that classifying a death arising from an anti-illegal drug operation as extrajudicial killing is wrong and misleading.[265]

In November, Former police chief and senator Bato dela Rosa filed a bill in the Senate proposing the decriminalization of usage of illegal drugs in a bid to decongest prisons and fill in the underutilized rehabilitation centers. This proposal was met with opposition from law enforcement agencies who believes such move would send a "wrong signal" to people that drug abuse is alright.[266]

The Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) on November 28 launched its Buhay Ay Ingatan, Droga'y Ayawan (BIDA; lit. 'Protect Life, Refuse Drugs') program apart from the campaign of law enforcement agencies. In coordination with local governments, the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) and the Department of Health, the DILG's program is focused on illegal drugs demand reduction and rehabilitation.[267]

In December, Dela Rosa called for action believing that there is a resurgence of drug syndicates which has come "back with a vengeance" citing two separate buy-bust operations which led to the arrest of police and PDEA agents.[268] Dela Rosa concluded that syndicates are emboldened to operate due to the departure of Duterte.[269] Interior Secretary Benhur Abalos in response points out that ₱10 billion worth of illegal drugs was seized since the start of the Marcos administration.[269]

In November 2024, the Department of Justice created a task force to conduct criminal investigation on EJK in the President Rodrigo Duterte drug war. It operates under the OSJPS, led by a senior assistant state prosecutor, regional prosecutor and 9 National Prosecution Service members.[270]

Conviction of Caloocan policemen

[edit]On June 18, 2024, Caloocan Regional Trial Court, Branch 121 Presiding Judge Maria Rowena Violago Alejandria sentenced Police Master Sergeant Virgilio Cervantes and police corporals Arnel de Guzman, Johnston Alacre, and Artemio Saguros for the homicide of father and son, Luis and Gabriel Bonifacio, during a 2016 anti-drug operation. This marked the fourth conviction in relation to Duterte's drug war;[271] the first was the 2018 Murders of Kian delos Santos, Carl Arnaiz and Reynaldo de Guzman.

Quad Committee of the House of Representatives hearings

[edit]In August 2024, the Philippine House of Representatives set up a panel to investigate possible links between Philippine Offshore Gaming Operators (POGOs), extrajudicial killings, drugs, and Chinese syndicates. The panel is composed of House dangerous drugs committee, human rights committee, public accounts committee, and public order and safety committee.[272] The Quad Committee held its first meeting on August 12.[273] It held its first hearing on August 16.[274]

Espenido's accusations against Senators Dela Rosa and Go

[edit]In August 2024, Jovie Espenido, a controversial[275] police officer involved in Duterte's war on drugs, testified before the House Committee accusing Senator Ronald dela Rosa of causing the dismissal of cases against drug lords Kerwin Espinosa and Mayor Reynaldo Parojinog. Espenido also accused Bong Go of sourcing intelligence funds from POGOs to fund the alleged "reward system" of Duterte's drug war.[276] Both Dela Rosa and Go vehemently denied Espenido's claims.[277]

Operations

[edit]The Philippine National Police manages Oplan Double Barrel as part of its involvement in President Rodrigo Duterte's campaign against illegal drugs in the Philippines. It consists of two main components: Oplan Tokhang and Oplan HVT.[278] Tokhang is characterized as the lower barrel approach while HVT which stands for high value targets is described as the police's high barrel approach.[279] The operation was launched in 2016.[280]

The Philippine police temporarily suspended its operations in October 2017 after a directive by President Duterte amidst reports of abuse by the police with the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) taking over as the leading agency against illegal drug activities in the Philippines. The police resumed operations in January 2018 with the police officially playing a supporting role to PDEA in Duterte's campaign.[279]

The latest iteration of Oplan Double Barrel is its Finale edition which was launched in March 14, 2022. It is also known as the Anti-Illegal Drugs Operations Thru Reinforcement and Education (ADORE).[281][282]

ADORE is still being implemented despite the end of Duterte's presidential term in June 2022 although his successor President Bongbong Marcos has indicated a policy shift towards focus on rehabilitation of small time drug users. Deaths still persisted despite this.[283][284] The PNP policy was placed under review in August 2024.[285]

Oplan Tokhang

[edit]One component of the war on drugs by the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte is Oplan Tokhang, derived from the Cebuano words tuktok (knock) and hangyo (plead). As the name suggests, Oplan Tokhang involves the police visiting the houses of individuals suspected to be involved in the illegal drug trade or as users, to persuade them to stop their activities and submit themselves to authority for potential rehabilitation. A more comprehensive guideline by the Philippine National Police then under the leadership of Police Chief Ronald dela Rosa was released prior to the resumption of police operations on the war on drugs in January 2019 after it was temporarily postponed.[286] Tokhang is characterized as a Police Community Relations operation.[287]

Under the guidelines, in a single operation, four police officers selected by the locality's police chief are designated as tokhangers to visit the suspects' houses in full uniform. They are to be accompanied by one member of the barangay, municipality, or city anti-drug abuse council, one representative from the PNP human-rights affairs office or any human rights advocate and at least one from the religious sector, members of the media or other prominent personalities in the area. They are only allowed to enter the suspect's house upon the suspect's consent or the house owner. The police coordinates with the Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency and the local anti-drug abuse councils for the conduct of the operations. The guidelines include the option for drug suspects to surrender themselves to the police or the barangay hall and the option to avail of rehabilitation. They are not required to sign any document. If the suspect refuses to surrender or engage with the visiting Oplan Tokhang team, their case is to be submitted to the Drug Enforcement Units, which will conduct relevant police operations including case build-up and negation.[286]

The policy was first used in a more local scale in Davao, when Dela Rosa was still the police chief of the locality, leading police visits to drug suspects houses. The word tokhang has become associated with killings related to the campaign against illegal drugs prior to the release of the guideline[286] with the PDEA chief General Aaron Aquino urging to discontinue the use "thokhang" to refer to the government's operations.[280]

Oplan HVT

[edit]Oplan High Value Targets (HVT) is a component of the Philippine National Police operations under Operation Double Barrel which aims to arrest and neutralize individuals which the police allege to be involved in the country's illegal drug trade. They include drug lords and pushers who operate in groups.[288] In its November 2016 report, the PNP Directorate for Intelligence said that of the 956 validated high-value targets identified by the national police since the start of the campaign, 23 were killed in police operations, 109 were arrested, and 361 surrendered.[288] This accounts for over 54.6% of the total identified HVTs while another 29 targets were listed as deaths under investigation. The PNP also reported that at least ₱1.445 billion worth of illegal drugs has been seized in the first four months of their campaign against HVTs.[288]

The high-value targets identified by the national police include Albuera Mayor Rolando Espinosa who earlier surrendered to the PNP before being killed in prison, and alleged number 2 Visayas drug lord Franz Sabalones, the brother of San Fernando, Cebu Mayor Fralz Sabalones, who surrendered to the PNP after being named by President Duterte in his narco-list speech.[289]

PDEA three-pronged strategy

[edit]The Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency announced in 2019 that it had adopted a three pronged strategy to enhance the Philippine government's war on drugs. These three prongs were composed of supply reduction, demand reduction, and harm reduction.[290]

During the Duterte Legacy campaign launch in January 2020, PDEA claimed victory via its three-pronged approach citing the successful activities.[291]

Under supply reduction, PDEA and other law enforcement agencies conducted high impact operations and arrested high-value targets. Authorities dismantled drug dens and shabu laboratories, seized billions of pesos of illegal drugs, and arrested over 200 thousand persons involved in illegal drugs.

Under demand reduction, advocacy campaign activities including lectures, seminars, conferences and film showings were conducted.

Under harm reduction, activities were conducted such as: "Balay Silangan", a community-based reform program for surrendering drug offenders, Project "Sagip Batang Solvent", which rescued street children—particularly those who were hooked on solvent-sniffing, drug-testing of public transportation drivers nationwide, and a "Drug-Free Workplace Program" for business establishments.

Although the three-pronged approach by PDEA was only adopted in April 2019, statistics of the activities above cited under victories in the PDEA's three-pronged approach under the Duterte Legacy campaign dated back to June 2016.[291]

Support of non-state actors

[edit]Rodrigo Duterte's campaign against illegal drugs was aided by non-government organizations including rebel groups and vigilantes. The Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) and its armed wing the New People's Army (NPA), initially cooperated with the government but withdrew its support for the government's campaign against drugs in August 2016 although the communist party vowed to continue its own operations, independent from the government's anti-drug campaign, against drug suspects.[3]

The Moro Islamic Liberation Front, a rebel group at truce with the government, forged a protocol with the Philippine government in July 2017 in which it pledged to arrest and turn over drug suspects taking refuge in the rebel group's camps and would allow the government to conduct its anti-drug operations in areas controlled by the rebel group.[4]

Killings by armed vigilantes, motorcycle-riding gunmen, and hired killers had led to accusations that the police was working with them during the campaign.[5][6]

Youth casualties

[edit]Children's rights non-governmental organizations reported that there were 101 child fatalities of the drug war from July 2016 through December 2018. Some children had to leave their homes and their family, fearing for their safety.[292] Government authorities have called the killings "collateral damage".[293]

On August 16, 2017, Kian Loyd delos Santos, a 17-year-old Grade 11 student, was shot dead in an antidrug operation in Caloocan.[294][295] CCTV footage appeared to show Kian being dragged by two policemen. Police say they killed him in self-defense, and retrieved a gun and two packets of methamphetamine.[294] Delos Santos was the son of an overseas Filipino worker, a key demographic in support of Duterte.[296] The teenager's death caused condemnation by senators.[297][298] His funeral on August 25, attended by more than a thousand people, was one of the largest protests to date against the drug war.[299]

Carl Angelo Arnaiz, a 19-year-old, last found in Cainta, Rizal, was tortured and shot dead also on August 17 (a day after Kian delos Santos was killed) by police after allegedly robbing a taxi in Caloocan.[300] His 14-year-old friend Reynaldo de Guzman, also known by the nickname "Kulot," was stabbed to death thirty times and thrown into a creek in Gapan, Nueva Ecija. The deaths of Arnaiz and de Guzman, along with the death of Kian delos Santos, triggered public outrage and condemnation.[301]

Human Rights Watch repeated their call for a UN investigation. HRW Asia director Phelim Kine commented: "The apparent willingness of Philippine police to deliberately target children for execution marks an appalling new level of depravity in this so-called drug war."[302] Duterte called the deaths of Arnaiz and de Guzman (the former being a relative of the President on his mother's side) "sabotage," believing that some groups are using the Philippine National Police to destroy the president's public image.[303] Presidential spokesman Abella said "It should not come as a surprise that these malignant elements would conspire to sabotage the president's campaign to rid the Philippines of illegal drugs and criminality," which "may include creating scenarios stoking public anger against the government."[302]

On August 23, 2016, a 5-year-old student named Danica May Garcia was killed by a stray bullet coming from unidentified gunmen in Dagupan during an anti-drug operation.[304] Another minor, 4-year old Skyler Abatayo of Cebu was killed by a stray bullet through an 'anti-drug operation'.[305] In the first year of the drug war, 54 children were recorded as casualties.[66] On the same week, a 15-year old by the name of Angelika Bonita (sometimes spelled "Angelica") was killed while riding inside the Toyota Hilux of 48-year-old narco-lawyer Rogelio Bato Jr., the attorney of Rolando Espinosa.[306][307][308] The two were cruising in a subdivision near a mall in Marasbaras, Tacloban when they were fired upon by M16s and .45 caliber guns. Both were killed instantly. Bato and Bonita were not related and questions surround their relationship. Rumors speculated that Bonita was Bato's girlfriend and that she was caught in the crossfire.[307]

Newly seated Senator Ronald dela Rosa made a statement about the death of a 3-year-old child named Myka Ulpina in crossfire during police operations in Rodriguez, Rizal on June 29, 2019, reacting to the incident by saying "shit happens".[309] It was alleged that Renato Dolofrina took his 3-year-old daughter hostage and that both were killed by the police after the father used the child as a "human shield."[310][311] However, the family denied the allegations of hostage taking, insisting that the child was killed by a stray bullet.[312] Also, a police officer who went undercover to buy crystal meth died in an operation after suspected drug user Dolofrina's companion discovered the ruse.[313] A few days later, several militant groups and netizens, as well as opposition Senators, condemned dela Rosa's remarks.[314][315] The Commission on Human Rights also condemned the child's death.[316] On July 8, 2019, dela Rosa apologized for his remarks and retracted his earlier statement, saying that the incident was "unfortunate."[309]

On August 2, 2023, Jerhode Jemboy Baltazar was shot (mistaken for a murderer) by Navotas cops in Barangay NBBS Kaunlaran (North Bay Boulevard South). In a 44-page decision promulgated on February 27, 2024, the Navotas RTC Branch 286 convicted Police Staff Sergeant Gerry Maliban of homicide and sentenced him to 4 years, 2 months, and 10 days up to six years, four months, and 20 days in prison and ordered him to pay Baltazar's heirs the sum of P50,000 in civil liability and P50,000 in moral damages. The court also convicted former Police Executive Master Sergeant Roberto Balais Jr., Police Staff Sergeant Nikko Esquilon, Police Corporal Edmark Jake Blanco, and Patrolman Benedict Mangada for the illegal discharge of firearms with sentence to 4 months and 1 day of imprisonment but it acquitted former Police Staff Sergeant Antonio Bugayong, noting that there were conflicting accounts on whether Bugayong fired his gun.[317][318]

Reactions

[edit]Accusations of genocide

[edit]Many observers have compared the mass killings of alleged users and dealers to a genocide,[319][320][321] and the ICC has opened a case of crimes against humanity.[322] Writing for the Washington Post, Maia Szalavitz argued that the campaign has not had much blowback because drug users are seen by many as worthless members of society and therefore easy targets.[323] In his book Dopeworld, former drug dealer[324][failed verification] turned author Niko Vorobyov has compared the drug war to the stages of annihilation outlined by Raul Hilberg to the Holocaust:

- Identification – singling out a group of people as subhuman. Duterte has said meth addicts have shrunken brains.[325][improper synthesis?]

- Confiscation and concentration – finding a way of taking those people's property, before taking themselves away, either to prisons, concentration camps, or to be deported.

- Annihilation – the final solution, where the unwanted people(s) are simply exterminated.[326]

At a press conference on September 30, 2016, Duterte appeared to make a comparison between the drug war and the Holocaust,[327][328] saying "Hitler massacred three million Jews. Now there are three million drug addicts. I'd be happy to slaughter them."[328] His remarks generated an international outcry; United States Secretary of Defense Ash Carter said the statement was "deeply troubling",[329][330] and the German government told the Philippine ambassador that Duterte's remarks were "unacceptable".[331] On October 2, Duterte announced, "I apologize profoundly and deeply to the Jewish"; he explained, "It's not really that I said something wrong but rather they don't really want you to tinker with the memory".[332][333]

St. John's University visiting professor Daniel Franklin Pilario said he needed to tell the stories of the widows and orphans, asking theologians what theology should they do after extrajudicial killings, the same with German theologians after the Holocaust.[334]

Investigations and reports

[edit]Investigations on the drug war have been conducted by lawmakers, human rights groups, academic institutions, and the media. Philippine law-enforcement agencies launched #RealNumbersPH on May 2, 2017, to publish data and publicity related to the drug war.[335]

In the Philippine Senate, on August 22, 2016, the Senate committee on justice and human rights opened a Senate inquiry on extrajudicial killings and police operations under the Philippine Drug War. After three public hearings, on September 19, the Senate ousted Senator Leila de Lima as chair of the committee leading the investigation and replaced her with Senator Richard Gordon as the new chair.[336]

In popular media

[edit]Television and film

[edit]In 2018, director Brillante Mendoza filmed Alpha: The Right to Kill, which follows themes of poverty, drugs, and corruption in the police force.[337] In the same year, Netflix aired its first series from the Philippines entitled Amo, also made by Mendoza.[338]

The long-running action drama series Ang Probinsyano has also tackled the issue in its storyline.[339] The show's portrayal of the PNP and its handling of the drug war, however, was criticized by the PNP Chief Oscar Albayalde because of its alleged negative portrayal.[340] The PNP at one point also withdrew its support for the show[341] and threatened legal action if the show's story was not changed.[342] Netizens, politicians, artists and others, on the other hand, defended the show's depiction of the police force and of the drug war.[343][344][345]

In 2018, Alyx Ayn Arumpac filmed the documentary Aswang, which frames events related to the drug war, trailing journalists and interviewing left-behinds of the victims. It premiered at the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (IDFA) in the Netherlands.[346]

Also in 2018, the action film BuyBust was released which similarly tackled the subject of the drug war. The film was released internationally and was an entry to the 2018 New York Asian Film Festival.[347]

In 2019, a multi-award-winning joint production by PBS and the BBC, On The President's Orders highlights the war on drugs in the Philippines. Produced and directed by two-time Emmy Award-winning and five-time BAFTA-nominated director James Jones, also filmed and directed by Emmy Award-winner for cinematography Olivier Sarbil.[348]

Music

[edit]Hustisya is a rap song about the drug war which was created by a local rap group "One Pro Exclusive" inspired by the death of their friend immortalized in a photograph often compared to Michelangelo's Pieta.[349]

In December 2016, American singer James Taylor posted on social media that he had canceled his concert in Manila, which was set for February 2017, citing the increasing number of deaths related to the drug war.[350][351]

The 2017 song Manila Ice, by musician Eyedress, and its music video depict violence and corruption and were created as a response to the drug war.[352][353]

In May 2019, PDEA called for a ban on rapper Shanti Dope's song Amatz for allegedly promoting marijuana use, which is illegal in the Philippines.[354][355] The Concerned Artists of the Philippines criticized the PDEA for the attempt to suppress freedom of expression.[356] In June 2019, the National Telecommunications Commission ordered the Kapisanan ng mga Brodkaster ng Pilipinas (Association of Broadcasters of the Philippines) to stop the airing of the song.[357]

The 2019 rap album Kolateral tells the story of the Philippine drug war through the eyes of the drug war's victims.[358][359] The album features 12 songs by artists BLKD (pronounced Balakid), Calix, and others.[358]

On December 10, 2019, Irish musician Bono of U2 sent a message to Duterte during his visit to Manila for concert tour, saying that he "can't compromise on human rights."[360] In a press conference, Bono said that he had been a member of Amnesty International and he is "critical" when it comes to human rights.[360] During the U2's concert, the band paid tribute to important women in the history such as late president Corazon Aquino and Rappler CEO Maria Ressa by flashing the images on the large screen.[361]

Photography

[edit]On April 11, 2017, The New York Times won a Pulitzer Prize for breaking news photography on their Philippine drug war report. The story was published on December 7, 2016, and was titled "They Are Slaughtering Us Like Animals."[362]

La Pieta[363] or the "Philippines Pieta," named after the sculpture by Michelangelo, refers to the photograph of Jennilyn Olayres holding the corpse of Michael Siaron, who was shot dead by unidentified assailants in Pasay, Metro Manila, on July 23, 2016. A piece of cardboard with the words "Wag tularan si Siaron dahil pusher umano" was placed on his body.[364] The image was widely used in the national press.[365] Malacañang alleged that the killing was committed by drug syndicates themselves.[364] One year and three months after Siaron was killed, the police identified the suspected assailant as Nesty Santiago through a ballistic exam on the recovered firearm.[366] Santiago was allegedly a member of a syndicate involved in robberies, car thefts, hired killings and illegal drugs. The Pasay city police declared Siaron's death as "case closed" since Santiago was also killed by riding-in-tandem on December 29, 2016.[366] No further investigation was made.[366]

A photo of a body of an alleged drug dealer, killed during a police anti-drug operation, in Manila by Noel Celis has been selected as one of Time magazine's top 100 photos of 2017.[367]

Mobile gaming