Peter and Wendy: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by Listener Sheogorath to version by Stelmaris. False positive? Report it. Thanks, ClueBot NG. (1499976) (Bot) |

→United Kingdom: added new information. |

||

| Line 145: | Line 145: | ||

=== United Kingdom === |

=== United Kingdom === |

||

The UK copyright originally expired at the end of 1987 (50 years after Barrie's death), but was revived in 1995 through 31 December 2007 by a [[Directive on harmonising the term of copyright protection|directive to harmonise copyright laws within the EU]]. Meanwhile in 1988, former Prime Minister [[James Callaghan]] sponsored a Parliamentary Bill granting a perpetual extension of some of the rights to the work, entitling the hospital to royalties for any performance, publication, or adaptation of the play. This is not a true [[perpetual copyright]] however, as it does not grant the hospital creative control over the use of the material, nor the right to refuse permission to use it. The law also does not cover the Peter Pan section of ''The Little White Bird'', which pre-dates the play and was not therefore an "adaptation" of it. The exact phrasing is in section 301 of, and Schedule 6 to, the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988:<blockquote>301. The provisions of Schedule 6 have effect for conferring on trustees for the benefit of the Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, London, a right to a royalty in respect of the public performance, commercial publication, broadcasting or inclusion in a cable programme service of the play 'Peter Pan' by Sir James Matthew Barrie, or of any adaptation of that work, notwithstanding that copyright in the work expired on 31 December 1987.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.legislation.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1988/Ukpga_19880048_en_28.htm#sdiv6 |title=Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 |publisher=Legislation.hmso.gov.uk |date=31 December 1987 |accessdate=2010-05-08}}</ref></blockquote> |

The UK copyright originally expired at the end of 1987 (50 years after Barrie's death), but was revived in 1995 through 31 December 2007 by a [[Directive on harmonising the term of copyright protection|directive to harmonise copyright laws within the EU]]. Meanwhile in 1988, former Prime Minister [[James Callaghan]] sponsored a Parliamentary Bill granting a perpetual extension of some of the rights to the work, entitling the hospital to royalties for any performance, publication, or adaptation of the play. This is not a true [[perpetual copyright]] however, as it does not grant the hospital creative control over the use of the material, nor the right to refuse permission to use it. The law also does not cover the Peter Pan section of ''The Little White Bird'', which pre-dates the play and was not therefore an "adaptation" of it. The exact phrasing is in section 301 of, and Schedule 6 to, the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988:<blockquote>301. The provisions of Schedule 6 have effect for conferring on trustees for the benefit of the Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, London, a right to a royalty in respect of the public performance, commercial publication, broadcasting or inclusion in a cable programme service of the play 'Peter Pan' by Sir James Matthew Barrie, or of any adaptation of that work, notwithstanding that copyright in the work expired on 31 December 1987.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.legislation.hmso.gov.uk/acts/acts1988/Ukpga_19880048_en_28.htm#sdiv6 |title=Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 |publisher=Legislation.hmso.gov.uk |date=31 December 1987 |accessdate=2010-05-08}}</ref></blockquote> |

||

According to GOSH: "Peter Pan is in |

|||

the public domain in the UK so no |

|||

royalties would be due on |

|||

publication of a new story using |

|||

characters from Barrie's original, |

|||

whether a sequel, prequel or other |

|||

spin-off. |

|||

"Royalties would only be owed to |

|||

us under Schedule 6 of the CDPA |

|||

(1988) if it's a new edition of the |

|||

original play or novel, a new |

|||

production or adaptation of the |

|||

play or any broadcast of the original |

|||

story. In the case of a new work |

|||

with a different storyline, a UK |

|||

author would not have to pay |

|||

royalties." |

|||

=== United States === |

=== United States === |

||

Revision as of 01:31, 12 February 2013

| Peter Pan; or, the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up | |

|---|---|

1904 announcement for original play at Duke of York's Theatre, London | |

| Written by | J. M. Barrie |

| Date premiered | 27 December 1904 |

| Original language | English |

Title page, 1911 UK edition | |

| Author | J. M. Barrie |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | F. D. Bedford |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy |

| Publisher | Hodder & Stoughton (UK) Charles Scribner's Sons (USA) |

Publication date | 11 October 1911 (UK) & (USA) |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 267 pp.; Frontispiece and 11 half-tone plates |

| Preceded by | The Little White Bird • Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens |

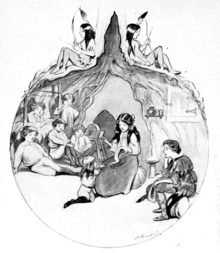

Peter Pan; or, the Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up or Peter and Wendy is J. M. Barrie's most famous work, in the form of a 1904 play and a 1911 novel, respectively. Both versions tell the story of Peter Pan, a mischievous little boy who can fly, and his adventures on the island of Neverland with Wendy Darling and her brothers, the fairy Tinker Bell, the Lost Boys, the Indian princess Tiger Lily, and the pirate Captain Hook. The play and novel were inspired by Barrie's friendship with the Llewelyn Davies family. Barrie continued to revise the play for years after its debut; the novel reflects one version of the story.

The play debuted in London on 27 December 1904 with Nina Boucicault, daughter of playwright Dion Boucicault, in the title role. A Broadway production was mounted in 1905 starring Maude Adams. It was later revived with such actresses as Marilyn Miller and Eva Le Gallienne. The play has since seen adaptation as a pantomime, stage musical, a television special, and several films, including a 1924 silent film, a 1953 animated Disney full-length feature, and a 2003 live action production. The play is now rarely performed in its original form on stage in the United Kingdom, whereas pantomime adaptations are frequently staged around Christmas. In the U.S., the original version has also been supplanted in popularity by the 1954 musical version, which became popular on television.

The novel was first published in 1911 by Hodder & Stoughton in the United Kingdom and Charles Scribner's Sons in the United States. The original book contains a frontispiece and 11 half-tone plates by artist F. D. Bedford (whose illustrations are still in copyright in the EU). The novel was first abridged by May Byron in 1915, with Barrie's permission, and published under the title Peter Pan and Wendy, the first time this form was used. This version was later illustrated by Mabel Lucie Attwell in 1921. The novel is now usually published under that title or simply Peter Pan. The script of the play, which Barrie had continued to revise since its first performance, was published in 1928. In 1929, Barrie gave the copyright of the Peter Pan works to Great Ormond Street Hospital, a children's hospital in London.

Background

Barrie created Peter Pan in stories he told to the sons of his friend Sylvia Llewelyn Davies, with whom he had forged a special relationship. Mrs. Llewelyn Davies' death from cancer came within a few years after the death of her husband. Barrie was named as co-guardian of the boys and unofficially adopted them.

The character's name comes from two sources: Peter Llewelyn Davies, one of the boys, and Pan, the mischievous Greek god of the woodlands. It has also been suggested that the inspiration for the character was Barrie's elder brother David, whose death in a skating accident at the age of fourteen deeply affected their mother. According to Andrew Birkin, author of J.M. Barrie and the Lost Boys, the death was "a catastrophe beyond belief, and one from which she never fully recovered... If Margaret Ogilvy [Barrie's mother as the heroine of his 1896 novel of that title] drew a measure of comfort from the notion that David, in dying a boy, would remain a boy for ever, Barrie drew inspiration."[1]

The Peter Pan character first appeared in print in the 1902 novel The Little White Bird, written for adults,[2] a fictionalised version of Barrie's relationship with the Llewelyn Davies children. The character was next used in the very successful stage play Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up that premiered in London on 27 December 1904.

In 1906, the portion of The Little White Bird which featured Peter Pan was published as the book Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens, with illustrations by Arthur Rackham.[3] Barrie then adapted the play into the 1911 novel Peter and Wendy (most often now published simply as Peter Pan).

The original draft of the play was entitled simply Anon: A Play. Barrie's working titles for it included The Great White Father[4] and Peter Pan, or The Boy Who Hated Mothers. Producer Charles Frohman disliked the title on the manuscript, in answer to which Barrie reportedly suggested The Boy Who Couldn't Grow Up; Frohman suggested changing it to Wouldn't.[5]

Plot summary

Although the character appeared previously in Barrie's book The Little White Bird,[3] the play and the novel based on it contain the portion of the Peter Pan mythos that is best known. The two versions differ in some details of the story, but have much in common. In both versions Peter makes night-time calls on the Darlings' house in Bloomsbury,[6] listening in on Mrs. Mary Darling's bedtime stories by the open window. One night Peter is spotted and, while trying to escape, he loses his shadow. On returning to claim it, Peter wakes Mary's daughter, Wendy Darling. Wendy succeeds in re-attaching his shadow to him, and Peter learns that she knows lots of bedtime stories. He invites her to Neverland to be a mother to his gang, the Lost Boys, children who were lost in Kensington Gardens. Wendy agrees, and her brothers John and Michael go along.

Their magical flight to Neverland is followed by many adventures. The children are blown out of the air by a cannon and Wendy is nearly killed by the Lost Boy Tootles. Peter and the Lost Boys build a little house for Wendy to live in while she recuperates (a structure that, to this day, is called a Wendy House.) Soon John and Michael adopt the ways of the Lost Boys.

Peter welcomes Wendy to his underground home, and she immediately assumes the role of mother figure. Peter takes the Darlings on several adventures, the first truly dangerous one occurring at Mermaids' Lagoon. At Mermaids' Lagoon, Peter and the Lost Boys save the princess Tiger Lily and become involved in a battle with the pirates, including the evil Captain Hook. Peter is wounded when Hook claws him. He believes he will die, stranded on a rock when the tide is rising, but he views death as "an awfully big adventure". Luckily, a bird allows him to use her nest as a boat, and Peter sails home.

Because he has saved Tiger Lily, the Indians are devoted to him, guarding his home from the next imminent pirate attack. Meanwhile, Wendy begins to fall in love with Peter, at least as a child, and asks Peter what kind of feelings he has for her. Peter says that he is like her faithful son. One day while telling stories to the Lost Boys and her brothers, John and Michael, Wendy recalls about her parents and then decides to take them back and return to England. Unfortunately, and unbeknownst to Peter, Wendy and the boys are captured by Captain Hook, who also tries to poison Peter's medicine while the boy is asleep. When Peter awakes, he learns from the fairy Tinker Bell that Wendy has been kidnapped – in an effort to please Wendy, he goes to drink his medicine. Tink does not have time to warn him of the poison, and instead drinks it herself, causing her near death. Tink tells him she could be saved if children believed in fairies. In one of the play's most famous moments, Peter turns to the audience watching the play and begs those who believe in fairies to clap their hands. At this there is usually an explosion of handclapping from the audience, and Tinker Bell is saved.

Peter heads to the ship. On the way, he encounters the ticking crocodile; Peter decides to copy the tick, so any animals will recognise it and leave him unharmed. He does not realise that he is still ticking as he boards the ship, where Hook cowers, mistaking him for the crocodile. While the pirates are searching for the croc, Peter sneaks into the cabin to steal the keys and frees the Lost Boys. When the pirates investigate a noise in the cabin, Peter defeats them. When he finally reveals himself, he and Hook fall to the climactic battle, which Peter easily wins. He kicks Hook into the jaws of the waiting crocodile, and Hook dies with the satisfaction that Peter had literally kicked him off the ship, which Hook considers "bad form". Then Peter takes control of the ship, and sails the seas back to London.

In the end, Wendy decides that her place is at home, much to the joy of her heartsick mother. Wendy then brings all the boys but Peter back to London. Before Wendy and her brothers arrive at their house, Peter flies ahead, to try and bar the window so Wendy will think her mother has forgotten her. But when he learns of Mrs Darling's distress, he bitterly leaves the window open and flies away. Peter returns briefly, and he meets Mrs. Darling, who has agreed to adopt the Lost Boys. She offers to adopt Peter as well, but Peter refuses, afraid they will "catch him and make him a man". It is hinted that Mary Darling knew Peter when she was a girl, because she is left slightly changed when Peter leaves.

Peter promises to return for Wendy every spring. The end of the play finds Wendy looking out through the window and saying into space, "You won't forget to come for me, Peter? Please, please don't forget".

An Afterthought

Four years after the premiere of the original production of Peter Pan, Barrie wrote an additional scene entitled An Afterthought, later included in the final chapter of Peter and Wendy. In this scene, Peter returns for Wendy years later, but she is now grown, with a daughter of her own. It is also revealed Wendy married one of the Lost Boys, although this is not mentioned in the novel, and it is never revealed which one she did marry. When Peter learns that Wendy has "betrayed" him by growing up, he is heartbroken until Wendy's daughter Jane agrees to come to Neverland as Peter's new mother. In the novel's last few sentences, Barrie mentions that Jane has grown up, and that Peter now takes her daughter Margaret to Neverland. Barrie says this cycle will go on forever as long as children are "innocent and heartless".

The Afterthought is only occasionally used in productions of the play, but it made a poignant conclusion to the musical production starring Mary Martin, and provided the premise for Disney's sequel to their animated adaptation of the story, Return to Never Land. This epilogue was filmed for the 2003 film but not included in the final version, though a rough cut of the sequence was included as an extra on the DVD of the film.

Characters

Peter Pan

Peter Pan is one of the protagonists of the play and the novel. He is described in the novel as a young boy who still has all his first teeth; he wears clothes made of leaves (autumn leaves in the play, skeleton leaves in the novel). He is the only boy able to fly without the help of fairy dust, and he can play the flute. Peter is afraid of nothing except mothers. He loves Wendy, but only as a mother figure, not as a romantic partner. Barrie attributes this to "the riddle of his existence".

The Darling Family

According to Barrie's description of the Darlings' house,[7] the family live in Bloomsbury, London.

- Wendy Darling – Wendy is the eldest child, their only daughter, and the protagonist of the novel. She loves the idea of homemaking and storytelling and wants to become a mother; her dreams consist of adventures in a little woodland house with her pet wolf. She bears a bit of (mutual) animosity toward Tiger Lily because of their similar affections toward Peter. She does not seem to feel the same way about Tinker Bell, but the fairy is constantly bad-mouthing her and even has attempted to have her killed. She grows up at the end of the novel, with a daughter (Jane) and a granddaughter (Margaret). She is portrayed with blonde, brown, or black hair in different stories. While it is not clear on whether or not she is in love with Peter, it is safe to assume that she does have feelings toward him, at least as a child. Perhaps consequently, Wendy is often referred to as the "mother" of the Lost Boys and, while Peter also considers her to be his "mother", he takes on the "father" role, insinuating that they play a married couple at least in their games.

- Several writers have stated that Barrie was the first to use the name Wendy in a published work, and that the source of the name was Barrie's childhood friend, Margaret Henley, 4-year-old daughter of poet William Ernest Henley, who pronounced the word "friend" as "Fweiendy", adapted by Barrie as "Wendy" in writing the play.[8] There is some evidence that the name Wendy may be related to the Welsh name Gwendolyn,[9][10] and it is also used as a diminutive variant of the eastern European name "Wanda",[11] but prior to its use in the Peter Pan stories, the name was not used as an independent first name.[12]

- John Darling – John is the middle child. He gets along well with Wendy, but he often argues with Michael. He is fascinated with pirates, and he once thought of becoming "Redhanded Jack". He dreams of living in an inverted boat on the sands, where he has no friends and spends his time shooting flamingos. He looks up to Peter Pan, but at times they clash due to Peter's nature of showing off. He also looks up to his father and dreams of running his firm one day when he is grown up. The character of John was named after Jack Llewelyn Davies.

- Michael Darling – Michael is the youngest child. He is approximately five years old, as he still wears the pinafores young Edwardian boys wear. He looks up to John and Wendy, dreaming of living in a wigwam where his friends visit at night. He was named after Michael Llewelyn Davies.

- Mr. and Mrs. Darling – George and Mary Darling are the children's loving parents. Mr. Darling is a pompous, blustering businessman who seeks to attract attention (from his co-workers to his wife and children), but he is really kind at heart. Mary Darling is described as an intelligent, romantic lady. It is hinted that she knew Peter Pan before her children were born. Mr. Darling was named after the eldest Llewellyn Davies boy, George, and Mrs. Darling was named after Mary Hodgson, the Davies boys' nurse. In the stage version, the same actor who plays Mr. Darling usually also plays Captain Hook.

- Nana – Nana is a Newfoundland dog who is employed as a nanny by the Darling family. Nana does not speak or do anything beyond the physical capabilities of a large dog, but acts with apparent understanding of her responsibilities. The character is played in stage productions by an actor in a dog costume. Barrie based the character of Nana on his dog Luath, a Newfoundland.

- Liza is the maidservant of the Darling family. She appears only in the first act, except in the 1954 musical. In this musical, she sees the Darling children fly off with Peter and begins to protest, but Michael sprinkles her with fairy dust and she ends up in Neverland. She returns with the children at the end. She is given two musical numbers in this adaptation.

Lost Boys

- Tootles – Tootles is the humblest Lost Boy because he often misses out on their violent adventures. Although he is often stupid, he is always the first to defend Wendy. Ironically, he shoots her before meeting her for the first time because of Tinker Bell's trickery. He grows up to become a judge.

- Nibs – Nibs is described as gay and debonair, probably the bravest Lost Boy. He says the only thing he remembers about his mother is she always wanted a cheque-book; he says he would love to give her one...if he knew what a cheque-book was. He's also the oldest and best looking Lost Boy.

- Slightly – Slightly is the most conceited because he believes he remembers the days before he was "lost". He is the only Lost Boy who "knows" his last name – he says his pinafore had the words "Slightly Soiled" written on the tag. He cuts whistles from the branches of trees, and dances to tunes he creates himself. Slightly is, apparently, a poor make-believer. He blows big breaths when he feels he is in trouble, and he eventually leads to Peter's almost-downfall.

- Curly – Curly is the most troublesome Lost Boy. In Disney's version of the story, he became "Cubby".

- The Twins – First and Second Twin know little about themselves – they are not allowed to, because Peter Pan does not know what Twins are (he thinks that twins are two parts of the same person, which, while not entirely correct, is right in the sense that the Twins finish each other's sentences (at least, in the movie adaptation).

Inhabitants of Neverland

- Tiger Lily is the proud, beautiful princess of the Piccaninny Tribe. In the book, the Indians of Neverland were portrayed in a nature that is now regarded as stereotypical.[13] Barrie portrayed them as primitive, warlike savages who spoke with guttural voice tones.[13] She is apparently old enough to be married, but she refuses any suitors because she desires Peter over all. She is jealous of Wendy and Tinker Bell. Tiger Lily is nearly killed by Captain Hook when she is seen boarding the Jolly Roger with a knife in her mouth, but Peter saves her.

- Tinker Bell is Peter Pan's fairy. She is described as a common fairy who mends pots and kettles and, though she is sometimes ill-behaved and vindictive, at other times she is helpful and kind to Peter (for whom she has romantic feelings). The extremes in her personality are explained by the fact that a fairy's size prevents her from holding more than one feeling at a time. In Barrie's book, by Peter's first annual return for Wendy, the boy has forgotten about Tinker Bell and suggests that she "is no more" for fairies do not live long.

- Captain James Hook is the vengeful pirate who lives to kill Peter Pan, not so much because Peter cut off his right hand, but because the boy is "cocky" and drives the genteel pirate to "madness". He is captain of the ship Jolly Roger. He attended Eton College before becoming a pirate and is obsessed with "good form". Hook meets his demise when a crocodile eats him. In the stage version, the same actor who plays Mr. Darling also plays this character.

- Mr. Smee is an Irish nonconformist pirate. He is the boatswain of the Jolly Roger. Smee is one of only two pirates to survive Peter Pan's massacre. He then makes his living saying he was the only man James Hook ever feared.

- Gentleman Starkey was once an usher at a public school. He is Captain Hook's first mate. Starkey is one of two pirates who escaped Peter Pan's massacre – he swims ashore and becomes baby-sitter to the Piccaninny Tribe. Peter Pan gives Starkey's hat to the Never Bird to use as a nest.

- Fairies – In the novel Peter and Wendy, published in 1911, there are fairies on Neverland. In the part of the story where Peter Pan and the Lost Boys built a house for Wendy on Neverland, Peter Pan stays up late that night to guard her from the pirates, but then the story says: "After a time he fell asleep, and some unsteady fairies had to climb over him on their way home from an orgy. Any of the other boys obstructing the fairy path at night they would have mischiefed, but they just tweaked Peter's nose and passed on." In the early 20th Century, the word "orgy" generally referred to a large group of people consuming alcohol.[14]

- Mermaids live in the Mermaids' Lagoon. J.M. Barrie states in the novel Peter and Wendy that the mermaids are only friendly to Peter, and that they will attempt to drown anyone else if they come close enough. It is especially dangerous to go to Mermaids' Lagoon at night, because that's when the mermaids sing to attract potential victims.

Major themes

This section possibly contains original research. (January 2010) |

The play's subtitle "The Boy Who Wouldn't Grow Up" underscores the primary theme: the conflict between the innocence of childhood and the responsibility of adulthood. Peter has literally chosen not to make the transition from one to the other, and encourages the other children to do the same. However, the opening line of the novel, "All children, except one, grow up", and the conclusion of the story indicates that this wish is unrealistic, and there is an element of tragedy in the alternative.

There is a slight romantic aspect to the story, which is sometimes played down or omitted completely. Wendy's flirtatious desire to kiss Peter, his desire for a mother figure, his conflicting feelings for Wendy, Tiger Lily, and Tinker Bell (each representing different female archetypes), and the symbolism of his fight with Captain Hook (traditionally played by the same actor as Wendy's father), all could possibly hint at a Freudian interpretation (see Oedipus Complex). Most "children's adaptations" of the play, including the 1953 Disney film, omit any romantic themes between Wendy and Peter, but Barrie's 1904 original, his 1911 novelisation of it, the 1954 Mary Martin musical, and the 1924 and 2003 feature films, all at least hint at the romantic elements.

Literary significance

Stage productions

The original stage production took place at the Duke of York's Theatre, London, on 27 December 1904. It starred Gerald du Maurier as Captain Hook and Mr Darling, and Nina Boucicault as Peter.[15] Members of Peter's Band were Joan Burnett (Tootles), Christine Silver (Nibs), A. W. Baskcomb (Slightly), Alice DuBarry (Curly), Pauline Chase (1st twin), Phyllis Beadon (2nd twin). Besides du Maurier, the pirates were: George Shelton (Smee), Sidney Harcourt (Gentleman Starkey), Charles Trevor (Cookson), Frederick Annerley (Cecco), Hubert Willis (Mullins), James English (Jukes), John Kelt (Noodler). Philip Darwin played Great Big Little Panther, Miriam Nesbitt was Tiger Lily, and Ela Q. May played Liza, (credited ironically as "Author of the Play"). First Pirate was played by Gerald Malvern, Second Pirate by J. Grahame, Black Pirate by S. Spencer, Crocodile by A. Ganker & C. Lawton, and the Ostrich by G. Henson.

Tinker Bell was represented on stage by a darting light "created by a small mirror held in the hand off-stage and reflecting a little circle of light from a powerful lamp"[16] and her voice was a "a collar of bells and two special ones that Barrie brought from Switzerland". However, a Miss "Jane Wren" or "Jenny Wren" was listed among the cast on the programmes of the original productions as playing Tinker Bell: this was meant as a joke that fooled H.M. Inspector of Taxes, who sent her a tax demand.[17]

Cecilia Loftus played Peter in the 1905–1906 production. Pauline Chase took the role from the 1906–07 London season until 1914 while Zena Dare was Peter on tour during most of that period. Jean Forbes-Robertson became a well-known Pan in London in the 1920s and 1930s.[18]

Following the success of his original London production, Charles Frohman mounted a production in New York City in 1905. The 1905 Broadway production starred Maude Adams, who would play the role on and off again for more than a decade and, in the U.S., was the actress most associated in the public's consciousness with the role for the next fifty years. It was produced again in the U.S. by the Civic Repertory Theater in November 1928 and December 1928, in which Eva LeGallienne directed and played the role of Peter Pan. Among musical theatre adaptations, the most successful in the U.S. has been an American musical version first produced on Broadway in 1954 starring Mary Martin, which was later videotaped for television and rebroadcast several times. Martin became the actress most associated with the role in the U.S. for several decades, although Sandy Duncan and Cathy Rigby each later toured extensively in this version and became well-known in the role.

It is traditional in productions of Peter Pan for Mr. Darling (the children's father) and Captain Hook to be played (or voiced) by the same actor. Although this was originally done simply to make full use of the actor (the characters appear in different sections of the story) with no thematic intent, some critics have perceived a similarity between the two characters as central figures in the lives of the children. It also brings a poignant juxtaposition between Mr. Darling's harmless bluster and Captain Hook's pompous vanity.

Adaptations

The story of Peter Pan has been a popular one for adaptation into other media. The story and its characters have been used as the basis for a number of motion pictures (live action and animated), stage musicals, television programs, a ballet, and ancillary media and merchandise. The best known of these are the 1953 animated feature film produced by Disney featuring the voice of 15-year-old film actor Bobby Driscoll (one of the first male actors in the title role, which was traditionally played by women); the series of musical productions (and their televised presentations) starring Mary Martin, Sandy Duncan, and Cathy Rigby; and the 2003 live-action feature film produced by P. J. Hogan starring Jeremy Sumpter.

There have been several additions to Peter Pan's story, including the authorised sequel novel Peter Pan in Scarlet, and the high-profile sequel films Return to Never Land and Hook. Various characters from the story have appeared in other places, especially Tinker Bell as a mascot and character of Disney. The characters are in the public domain in some jurisdictions, leading to unauthorised extensions to the mythos and uses of the characters. Some of these have been controversial, such as a series of prequels by Dave Barry and Ridley Pearson, and Lost Girls, a sexually explicit graphic novel by Alan Moore and Melinda Gebbie, featuring Wendy Darling and the heroines of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz and Alice's Adventures in Wonderland.

Copyright status

The copyright status of the story of Peter Pan and its characters has been the subject of dispute, particularly as the original version began to enter the public domain in various jurisdictions. In 1929, Barrie gave the copyright to the works featuring Peter Pan to Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH), Britain's leading children's hospital, and requested that the value of the gift should never be disclosed; this gift was confirmed in his will. GOSH has exercised these rights internationally to support the work of the institution.

United Kingdom

The UK copyright originally expired at the end of 1987 (50 years after Barrie's death), but was revived in 1995 through 31 December 2007 by a directive to harmonise copyright laws within the EU. Meanwhile in 1988, former Prime Minister James Callaghan sponsored a Parliamentary Bill granting a perpetual extension of some of the rights to the work, entitling the hospital to royalties for any performance, publication, or adaptation of the play. This is not a true perpetual copyright however, as it does not grant the hospital creative control over the use of the material, nor the right to refuse permission to use it. The law also does not cover the Peter Pan section of The Little White Bird, which pre-dates the play and was not therefore an "adaptation" of it. The exact phrasing is in section 301 of, and Schedule 6 to, the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988:

301. The provisions of Schedule 6 have effect for conferring on trustees for the benefit of the Hospital for Sick Children, Great Ormond Street, London, a right to a royalty in respect of the public performance, commercial publication, broadcasting or inclusion in a cable programme service of the play 'Peter Pan' by Sir James Matthew Barrie, or of any adaptation of that work, notwithstanding that copyright in the work expired on 31 December 1987.[19]

According to GOSH: "Peter Pan is in the public domain in the UK so no royalties would be due on publication of a new story using characters from Barrie's original, whether a sequel, prequel or other spin-off. "Royalties would only be owed to us under Schedule 6 of the CDPA (1988) if it's a new edition of the original play or novel, a new production or adaptation of the play or any broadcast of the original story. In the case of a new work with a different storyline, a UK author would not have to pay royalties."

United States

Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) claims that U.S. legislation effective in 1978 and again in 1998, which extended the copyright of the play script published in 1928, gives them copyright over "Peter Pan" in general until 2023, although GOSH acknowledges that the copyright of the novel version, published in 1911, has expired in the United States.[20]

Previously, GOSH's claim of U.S. copyright had been contested by various parties. J. E. Somma sued GOSH to permit the U.S. publication of her sequel After the Rain, A New Adventure for Peter Pan. GOSH and Somma settled out of court in March 2005, issuing a joint statement which characterised her novel – which she had argued was a commentary on the original work, rather than a mere derivative of it – as "fair use" of the hospital's "U.S. intellectual property rights". Their confidential settlement did not set any legal precedent, however.[21] Disney was a long-time licensee to the animation rights, and cooperated with the hospital when its copyright claim was clear, but in 2004 Disney published Dave Barry's and Ridley Pearson's Peter and the Starcatchers in the U.S., the first of several sequels, without permission and without making royalty payments. In 2006, Top Shelf Productions published in the U.S. Lost Girls, a pornographic graphic novel featuring Wendy Darling, also without permission or royalties.

Other jurisdictions

The original versions of the play and novel are in the public domain in countries where the term of copyright is 70 years (or less) after the death of the creators. This includes the European Union (except Spain), Australia, Canada (where Somma's book was first published without incident), and most other countries (see list of countries' copyright length).

However, the work is still under copyright in several countries: until 2013 in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, where copyright lasts 75 years after the author's death; in Colombia and Spain until 2018, where the applicable term is 80 years after death. (It would also be under copyright in Côte d'Ivoire, Guatemala, and Honduras, but these countries recognise the "rule of the shorter term", which means that the term of the country of origin applies if it is shorter than their local term.)

See also

- List of works based on Peter Pan

- Peter Pan's Flight, an attraction at many of the Walt Disney Parks and Resorts.

- Puer aeternus

References

- ^ Birkin, Andrew: J M Barrie & the Lost Boys (Yale University Press, 2003)

- ^ Barrie, J.M. (1999). Peter Hollindale (Introduction and Notes) (ed.). Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens and Peter and Wendy. Oxford Press. pp. xix. ISBN 0-19-283929-2.

- ^ a b Birkin, Andrew (2003). J.M. Barrie & the Lost Boys. Yale University Press. p. 47. ISBN 0-300-09822-7.

- ^ Birkin, Andrew (2003). J.M. Barrie & the Lost Boys. Yale University Press. p. 105. ISBN 0-300-09822-7.

- ^ "It's Behind You – Peter Pan". Its-behind-you.com. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ Act I, Peter Pan (Hodder & Stoughton 1928)

- ^ Act I, Peter PanHodder & Stoughton, 1928

- ^ Barrie, J.M. (1999). Peter Hollindale (Introduction and Notes) (ed.). Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens and Peter and Wendy. Oxford Press. p. 231. ISBN 0-19-283929-2.

- ^ Norman, Teresa (2003). A World of Baby Names. Perigee. pp. 130, 147. ISBN 0-399-52894-6.

- ^ "Behind the Name: the Etymology and History of First Names: "Wendy"".

- ^ Norman, Teresa (2003). A World of Baby Names. Perigee. p. 196. ISBN 0-399-52894-6.

- ^ Withycombe, Elizabeth Gidley (1977). Oxford Dictionary of English Christian Names. Clarendon. p. 293. ISBN 0-19-869124-6.

- ^ a b "The Movies and Ethnic Representation: Native Americans". Lib.berkeley.edu. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ Barrie, J.M. (1999). Peter Hollindale (ed.). Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens and Peter and Wendy. Oxford Press. p. 132. ISBN 0-19-283929-2.

- ^ Duke Of York's Theatre. "Peter Pan.", Reviews, The Times, 28 December 1904

- ^ Roger Lancelyn Green, Fifty Years of Peter Pan, Peter Davies Publishing, 1954

- ^ Roger Lancelyn Green, J. M. Barrie, Bodley Head, 1960

- ^ Hanson, Bruce K. Peter Pan on Stage and Screen, 1904-2010, McFarland (2011), pp. 151–53 ISBN 0786447788

- ^ "Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988". Legislation.hmso.gov.uk. 31 December 1987. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ "Copyright – Publishing and Stage". GOSH. 31 December 2007. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

- ^ "Stanford Center for Internet and Society". Web.archive.org. Archived from the original on 27 October 2006. Retrieved 8 May 2010.

General references

- Barrie, James Matthew and Scott Gustafson (illustrator). Peter Pan: The Complete and Unabridged Text, Viking Press, October 1991. (ISBN 0-670-84180-3).

- Birkin, Andrew. J.M. Barrie and the Lost Boys.

- The original text of

- Peter Pan and Wendy at Project Gutenberg (Note: Project Gutenberg claims a copyright "to assist in the preservation of this edition in proper usage". It is only to be distributed in the United States). (This is the novel, not the script of the play.)

- People's memories of the Peter Pan statue

- The Victorian Web: Frampton's Peter Pan statue

- The Adventures of Peter Pan (electronic text) (actually just "Peter Pan and Wendy" with the title changed)

- Murray, Roderick. "An Awfully Big Adventure: John Crook's Incidental Music to Peter Pan". The Gaiety (Spring 2005). (pp. 35–36)