Perineural invasion

In pathology, perineural invasion, abbreviated PNI, refers to the invasion of cancer to the space surrounding a nerve. It is common in head and neck cancer, prostate cancer and colorectal cancer.

Unlike perineural spread (PNS), which is defined as gross tumor spread along a larger, typically named nerve that is at least partially distinct from the main tumor mass and can be seen on imaging studies, PNI is defined as tumor cells infiltrating small, unnamed nerves that can only be seen microscopically but not radiologically and are often confined to the main tumor mass. The transition from PNI to PNS is not precisely defined, but PNS is detectable on MRI and may have clinical manifestations that correlate with the affected nerve.[1]

Significance

[edit]Cancers with PNI usually have a poorer prognosis,[2] as PNI is thought to be indicative of perineural spread, which can make resection of malignant lesions more difficult. Cancer cells use nerves as routes of metastasis, which could explain why PNI is associated with poorer outcomes.[3]

Prostate cancer

[edit]In prostate cancer, PNI in needle biopsies is poor prognosticator;[2] however, in prostatectomy specimens it is unclear whether it carries a worse prognosis.[4]

In one study, PNI was found in approximately 90% of radical prostatectomy specimens, and PNI outside of the prostate, especially, was associated with a poorer prognosis.[5] However, there exists controversies about whether PNI has prognostic significance toward cancer malignancy.

In perineural invasion, cancer cells proliferate around peripheral nerves and eventually invade them. Cancer cells migrate in response to different mediators released by autonomic and sensory fibers. Tumor cells secrete CCL2 and CSF-1 to accumulate endoneurial macrophages and, at the same time, release factors that stimulate perineural invasion. Schwann cells release TGFβ, increasing the aggressiveness of cancer cells through TGFβ-RI. Schwann cells drive perineural invasion, cancer cells interact directly with Schwann cells via NCAM1 to invade and migrate along nerves.[6]

Head and neck cancer

[edit]PNI and PNS are considered an unfavorable prognostic factors in head and neck cancer of virtually all sites, associated with poor local and regional disease control, probability of locoregional and distant metastases, disease recurrence, and lower survival rate. Although adenoid cystic carcinoma accounts for only 1-3% of head and neck tumors, it has the highest relative incidence of PNI. PNI is also commonly found in patients with salivary duct carcinomas, polymorphous low-grade adenocarcinomas, cutaneous malignancies, desmoplastic melanomas, myelomas, lymphomas, and leukemias. If PNS is not detected, there is a high risk of cancer progression. PNS recurrence is rarely resectable, and repeated irradiation has greater toxic side effects and fewer benefits compared with initial early treatment. The trigeminal nerve and facial nerve are the most commonly affected nerves primarily because of their extensive innervation area, although virtually any cranial nerve and its branches can provide a route for the PNS.[1]

Additional images

[edit]-

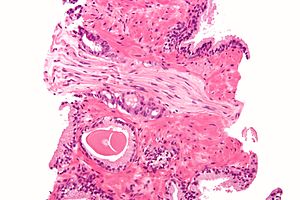

Micrograph demonstrating perineural invasion. HPS stain.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Medvedev, Olga; Hedesiu, Mihaela; Ciurea, Anca; Lenghel, Manuela; Rotar, Horatiu; Dinu, Cristian; Roman, Rares; Termure, Dragos; Csutak, Csaba (2021-06-29). "Perineural spread in head and neck malignancies: imaging findings - an updated literature review". Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. doi:10.17305/bjbms.2021.5897. ISSN 1840-4812. PMC 8860315. PMID 34255618.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- ^ a b Potter, SR.; Partin, AW. (2000). "The significance of perineural invasion found on needle biopsy of the prostate: implications for definitive therapy". Rev Urol. 2 (2): 87–90. PMC 1476100. PMID 16985741.

- ^ Gillespie, Shawn; Monje, Michelle (2020). "The Neural Regulation of Cancer". Annual Review of Cancer Biology. 4: 371–390. doi:10.1146/annurev-cancerbio-030419-033349.

- ^ Bostwick, DG.; Foster, CS. (Nov 1999). "Predictive factors in prostate cancer: current concepts from the 1999 College of American Pathologists Conference on Solid Tumor Prognostic Factors and the 1999 World Health Organization Second International Consultation on Prostate Cancer". Semin Urol Oncol. 17 (4): 222–72. PMID 10632123.

- ^ Merrilees, AD.; Bethwaite, PB.; Russell, GL.; Robinson, RG.; Delahunt, B. (Sep 2008). "Parameters of perineural invasion in radical prostatectomy specimens lack prognostic significance". Mod Pathol. 21 (9): 1095–100. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2008.81. PMID 18500264.

- ^ Cervantes-Villagrana RD, Albores-García D, Cervantes-Villagrana AR, García-Acevez SJ (18 June 2020). "Tumor-induced Neurogenesis and Immune Evasion as Targets of Innovative Anti-Cancer Therapies". Signal Transduct Target Ther. 5 (1): 99. doi:10.1038/s41392-020-0205-z. PMC 7303203. PMID 32555170.