Peptic ulcer disease: Difference between revisions

m Reverted good faith edits by 24.5.174.60 talk, (HG) |

|||

| Line 157: | Line 157: | ||

Peptic ulcer disease had a tremendous effect on morbidity and mortality until the last decades of the 20th century, when epidemiological trends started to point to an impressive fall in its incidence.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://lib.bioinfo.pl/meid:32219| title=Peptic ulcer disease |accessdate= 2010-06-18}}</ref> The reason that the rates of peptic ulcer disease decreased is thought to be the development of new effective medication and acid suppressants and the discovery of the cause of the condition, ''H. pylori''. |

Peptic ulcer disease had a tremendous effect on morbidity and mortality until the last decades of the 20th century, when epidemiological trends started to point to an impressive fall in its incidence.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://lib.bioinfo.pl/meid:32219| title=Peptic ulcer disease |accessdate= 2010-06-18}}</ref> The reason that the rates of peptic ulcer disease decreased is thought to be the development of new effective medication and acid suppressants and the discovery of the cause of the condition, ''H. pylori''. |

||

In the [[United States]] about 4 million people have active peptic ulcers and about 350,000 new cases are diagnosed each year. Four times as many duodenal ulcers as gastric ulcers are diagnosed. Approximately 3,000 deaths per year in the United States are due to duodenal ulcer and 3,000 to gastric ulcer.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kurata JH, Haile BM |title=Epidemiology of peptic ulcer disease |journal=Clin Gastroenterol |volume=13 |issue=2 |pages=289–307 |year=1984 |month= |

In the [[United States]] about 4 million people have active peptic ulcers and about 350,000 new cases are diagnosed each year. Four times as many duodenal ulcers as gastric ulcers are diagnosed. Approximately 3,000 deaths per year in the United States are due to duodenal ulcer and 3,000 to gastric ulcer.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kurata JH, Haile BM |title=Epidemiology of peptic ulcer disease |journal=Clin Gastroenterol |volume=13 |issue=2 |pages=289–307 |year=1984 |month=Maydfgbgebebfevfebfebfebfe |

||

|pmid=6378441 }}</ref> |

|||

=== Diet as a predisposing cause=== |

=== Diet as a predisposing cause=== |

||

Revision as of 12:12, 23 April 2013

| Peptic ulcer disease | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Gastroenterology |

A peptic ulcer, also known as peptic ulcer disease (PUD),[1] is the most common ulcer of an area of the gastrointestinal tract that is usually acidic and thus extremely painful. It is defined as mucosal erosions equal to or greater than 0.5 cm. As many as 70–90% of such ulcers are associated with Helicobacter pylori, a helical-shaped bacterium that lives in the acidic environment of the stomach; however, only 40% of those cases go to a doctor[citation needed]. Ulcers can also be caused or worsened by drugs such as aspirin, ibuprofen, and other NSAIDs.[2]

Four times as many peptic ulcers arise in the duodenum—the first part of the small intestine, just after the stomach—as in the stomach itself. About 4% of gastric ulcers are caused by a malignant tumor, so multiple biopsies are needed to exclude cancer. Duodenal ulcers are generally benign.

Classification

By Region/Location

- Duodenum (called duodenal ulcer)

- Esophagus (called esophageal ulcer)

- Stomach (called gastric ulcer)

- Meckel's diverticulum (called Meckel's diverticulum ulcer; is very tender with palpation)

Modified Johnson Classification of peptic ulcers:

- Type I: Ulcer along the body of the stomach, most often along the lesser curve at incisura angularis along the locus minoris resistantiae.

- Type II: Ulcer in the body in combination with duodenal ulcers. Associated with acid oversecretion.

- Type III: In the pyloric channel within 3 cm of pylorus. Associated with acid oversecretion.

- Type IV: Proximal gastroesophageal ulcer

- Type V: Can occur throughout the stomach. Associated with chronic NSAID use (such as aspirin).

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of a peptic ulcer can be

- abdominal pain, classically epigastric strongly correlated to mealtimes. In case of duodenal ulcers the pain appears about three hours after taking a meal;

- bloating and abdominal fullness;

- waterbrash (rush of saliva after an episode of regurgitation to dilute the acid in esophagus - although this is more associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease);

- nausea, and copious vomiting;

- loss of appetite and weight loss;

- hematemesis (vomiting of blood); this can occur due to bleeding directly from a gastric ulcer, or from damage to the esophagus from severe/continuing vomiting.

- melena (tarry, foul-smelling feces due to oxidized iron from hemoglobin);

- rarely, an ulcer can lead to a gastric or duodenal perforation, which leads to acute peritonitis. This is extremely painful and requires immediate surgery.

A history of heartburn, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and use of certain forms of medication can raise the suspicion for peptic ulcer. Medicines associated with peptic ulcer include NSAID (non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs) that inhibit cyclooxygenase, and most glucocorticoids (e.g. dexamethasone and prednisolone).

In patients over 45 with more than two weeks of the above symptoms, the odds for peptic ulceration are high enough to warrant rapid investigation by esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

The timing of the symptoms in relation to the meal may differentiate between gastric and duodenal ulcers: A gastric ulcer would give epigastric pain during the meal, as gastric acid production is increased as food enters the stomach. Symptoms of duodenal ulcers would initially be relieved by a meal, as the pyloric sphincter closes to concentrate the stomach contents, therefore acid is not reaching the duodenum. Duodenal ulcer pain would manifest mostly 2–3 hours after the meal, when the stomach begins to release digested food and acid into the duodenum.

Also, the symptoms of peptic ulcers may vary with the location of the ulcer and the patient's age. Furthermore, typical ulcers tend to heal and recur and as a result the pain may occur for few days and weeks and then wane or disappear.[3] Usually, children and the elderly do not develop any symptoms unless complications have arisen.

Burning or gnawing feeling in the stomach area lasting between 30 minutes and 3 hours commonly accompanies ulcers. This pain can be misinterpreted as hunger, indigestion or heartburn. Pain is usually caused by the ulcer but it may be aggravated by the stomach acid when it comes into contact with the ulcerated area. The pain caused by peptic ulcers can be felt anywhere from the navel up to the sternum, it may last from few minutes to several hours and it may be worse when the stomach is empty. Also, sometimes the pain may flare at night and it can commonly be temporarily relieved by eating foods that buffer stomach acid or by taking anti-acid medication.[4] However, peptic ulcer disease symptoms may be different for every sufferer.[5]

Complications

- Gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common complication. Sudden large bleeding can be life-threatening.[6] It occurs when the ulcer erodes one of the blood vessels, such as the gastroduodenal artery.

- Perforation (a hole in the wall) often leads to catastrophic consequences. Erosion of the gastro-intestinal wall by the ulcer leads to spillage of stomach or intestinal content into the abdominal cavity. Perforation at the anterior surface of the stomach leads to acute peritonitis, initially chemical and later bacterial peritonitis. The first sign is often sudden intense abdominal pain. Posterior wall perforation leads to bleeding due to involvement of gastroduodenal artery that lies posterior to the 1st part of duodenum.

- Perforation and penetration are when the ulcer continues into adjacent organs such as the liver and pancreas.[3]

- Gastric outlet obstruction is the narrowing of pyloric canal by scarring and swelling of gastric antrum and duodenum due to peptic ulcers. Patient often presents with severe vomiting without bile.

- Cancer is included in the differential diagnosis (elucidated by biopsy), Helicobacter pylori as the etiological factor making it 3 to 6 times more likely to develop stomach cancer from the ulcer.[3]

Cause

A major causative factor (60% of gastric and up to 90% of duodenal ulcers) is chronic inflammation due to Helicobacter pylori that colonizes the antral mucosa.[7] The immune system is unable to clear the infection, despite the appearance of antibodies. Thus, the bacterium can cause a chronic active gastritis (type B gastritis), resulting in a defect in the regulation of gastrin production by that part of the stomach, and gastrin secretion can either be increased, or as in most cases, decreased, resulting in hypo- or achlorhydria. Gastrin stimulates the production of gastric acid by parietal cells. In H. pylori colonization responses to increased gastrin, the increase in acid can contribute to the erosion of the mucosa and therefore ulcer formation. Studies in the varying occurrence of ulcers in third world countries despite high H. pylori colonization rates suggest dietary factors play a role in the pathogenesis of the disease.[8]

Another major cause is the use of NSAIDs. The gastric mucosa protects itself from gastric acid with a layer of mucus, the secretion of which is stimulated by certain prostaglandins. NSAIDs block the function of cyclooxygenase 1 (cox-1), which is essential for the production of these prostaglandins. COX-2 selective anti-inflammatories (such as celecoxib or the since withdrawn rofecoxib) preferentially inhibit cox-2, which is less essential in the gastric mucosa, and roughly halve the risk of NSAID-related gastric ulceration.

The incidence of duodenal ulcers has dropped significantly during the last 30 years, while the incidence of gastric ulcers has shown a small increase, mainly caused by the widespread use of NSAIDs. The drop in incidence is considered to be a cohort-phenomenon independent of the progress in treatment of the disease. The cohort-phenomenon is probably explained by improved standards of living which has lowered the incidence of H. pylori infections.[9]

Although some studies have found correlations between smoking and ulcer formation,[10] others have been more specific in exploring the risks involved and have found that smoking by itself may not be much of a risk factor unless associated with H. pylori infection.[11][12][13][nb 1] Some suggested risk factors such as diet, and spice consumption, were hypothesized as ulcerogens (helping cause ulcers) until late in the 20th century, but have been shown to be of relatively minor importance in the development of peptic ulcers.[14] Caffeine and coffee, also commonly thought to cause or exacerbate ulcers, have not been found to affect ulcers to any significant extent.[15][16] Similarly, while studies have found that alcohol consumption increases risk when associated with H. pylori infection, it does not seem to independently increase risk, and even when coupled with H. pylori infection, the increase is modest in comparison to the primary risk factor.[11][17][nb 2]

Gastrinomas (Zollinger Ellison syndrome), rare gastrin-secreting tumors, also cause multiple and difficult-to-heal ulcers.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis is mainly established based on the characteristic symptoms. Stomach pain is usually the first signal of a peptic ulcer. In some cases, doctors may treat ulcers without diagnosing them with specific tests and observe whether the symptoms resolve, thus indicating that their primary diagnosis was accurate.

Confirmation of the diagnosis is made with the help of tests such as endoscopies or barium contrast x-rays. The tests are typically ordered if the symptoms do not resolve after a few weeks of treatment, or when they first appear in a person who is over age 45 or who has other symptoms such as weight loss, because stomach cancer can cause similar symptoms. Also, when severe ulcers resist treatment, particularly if a person has several ulcers or the ulcers are in unusual places, a doctor may suspect an underlying condition that causes the stomach to overproduce acid.[3]

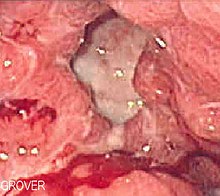

An esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), a form of endoscopy, also known as a gastroscopy, is carried out on patients in whom a peptic ulcer is suspected. By direct visual identification, the location and severity of an ulcer can be described. Moreover, if no ulcer is present, EGD can often provide an alternative diagnosis.

One of the reasons that blood tests are not reliable for accurate peptic ulcer diagnosis on their own is their inability to differentiate between past exposure to the bacteria and current infection. Additionally, a false negative result is possible with a blood test if the patient has recently been taking certain drugs, such as antibiotics or proton pump inhibitors.[18]

The diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori can be made by:

- Urea breath test (noninvasive and does not require EGD);

- Direct culture from an EGD biopsy specimen; this is difficult to do, and can be expensive. Most labs are not set up to perform H. pylori cultures;

- Direct detection of urease activity in a biopsy specimen by rapid urease test;

- Measurement of antibody levels in blood (does not require EGD). It is still somewhat controversial whether a positive antibody without EGD is enough to warrant eradication therapy;

- Stool antigen test;

- Histological examination and staining of an EGD biopsy.

The breath test uses radioactive carbon atom to detect H. pylori.[19] To perform this exam the patient will be asked to drink a tasteless liquid which contains the carbon as part of the substance that the bacteria breaks down. After an hour, the patient will be asked to blow into a bag that is sealed. If the patient is infected with H. pylori, the breath sample will contain radioactive carbon dioxide. This test provides the advantage of being able to monitor the response to treatment used to kill the bacteria.

The possibility of other causes of ulcers, notably malignancy (gastric cancer) needs to be kept in mind. This is especially true in ulcers of the greater (large) curvature of the stomach; most are also a consequence of chronic H. pylori infection.

If a peptic ulcer perforates, air will leak from the inside of the gastrointestinal tract (which always contains some air) to the peritoneal cavity (which normally never contains air). This leads to "free gas" within the peritoneal cavity. If the patient stands erect, as when having a chest X-ray, the gas will float to a position underneath the diaphragm. Therefore, gas in the peritoneal cavity, shown on an erect chest X-ray or supine lateral abdominal X-ray, is an omen of perforated peptic ulcer disease.

Macroscopic appearance

Gastric ulcers are most often localized on the lesser curvature of the stomach. The ulcer is a round to oval parietal defect ("hole"), 2 to 4 cm diameter, with a smooth base and perpendicular borders. These borders are not elevated or irregular in the acute form of peptic ulcer, regular but with elevated borders and inflammatory surrounding in the chronic form. In the ulcerative form of gastric cancer the borders are irregular. Surrounding mucosa may present radial folds, as a consequence of the parietal scarring.

Microscopic appearance

A gastric peptic ulcer is a mucosal defect which penetrates the muscularis mucosae and lamina propria, produced by acid-pepsin aggression. Ulcer margins are perpendicular and present chronic gastritis. During the active phase, the base of the ulcer shows 4 zones: inflammatory exudate, fibrinoid necrosis, granulation tissue and fibrous tissue. The fibrous base of the ulcer may contain vessels with thickened wall or with thrombosis.[20]

Differential diagnosis

Treatment

Younger patients with ulcer-like symptoms are often treated with antacids or H2 antagonists before EGD is undertaken. Bismuth compounds may actually reduce or even clear organisms [citation needed], though the warning labels of some bismuth subsalicylate products indicate that the product should not be used by someone with an ulcer.[21]

Patients who are taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) may also be prescribed a prostaglandin analogue (Misoprostol) in order to help prevent peptic ulcers, which are a side-effect of the NSAIDs.

When H. pylori infection is present, the most effective treatments are combinations of 2 antibiotics (e.g. Clarithromycin, Amoxicillin, Tetracycline, Metronidazole) and 1 proton pump inhibitor (PPI), sometimes together with a bismuth compound. In complicated, treatment-resistant cases, 3 antibiotics (e.g. amoxicillin + clarithromycin + metronidazole) may be used together with a PPI and sometimes with bismuth compound. An effective first-line therapy for uncomplicated cases would be Amoxicillin + Metronidazole + Pantoprazole (a PPI). In the absence of H. pylori, long-term higher dose PPIs are often used.

Treatment of H. pylori usually leads to clearing of infection, relief of symptoms and eventual healing of ulcers. Recurrence of infection can occur and retreatment may be required, if necessary with other antibiotics. Since the widespread use of PPI's in the 1990s, surgical procedures (like "highly selective vagotomy") for uncomplicated peptic ulcers became obsolete.

Perforated peptic ulcer is a surgical emergency and requires surgical repair of the perforation. Most bleeding ulcers require endoscopy urgently to stop bleeding with cautery, injection, or clipping.

Ranitidine and famotidine, which are both H2 antagonists, provide relief of peptic ulcers, heartburn, indigestion and excess stomach acid and prevention of these symptoms associated with excessive consumption of food and drink. Ranitidine and famotidine are available over the counter at pharmacies, both as brand-name drugs and as generics, and work by decreasing the amount of acid the stomach produces allowing healing of ulcers.[22]

Sucralfate (Carafate) has also been a successful treatment of peptic ulcers.[23]

Epidemiology

The lifetime risk for developing a peptic ulcer is approximately 10%.[25]

In Western countries the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infections roughly matches age (i.e., 20% at age 20, 30% at age 30, 80% at age 80 etc.). Prevalence is higher in third world countries where it is estimated at about 70% of the population, whereas developed countries show a maximum of 40% ratio. Overall, H. pylori infections show a worldwide decrease, more so in developed countries. Transmission is by food, contaminated groundwater, and through human saliva (such as from kissing or sharing food utensils).[26]

A minority of cases of H. pylori infection will eventually lead to an ulcer and a larger proportion of people will get non-specific discomfort, abdominal pain or gastritis.

Peptic ulcer disease had a tremendous effect on morbidity and mortality until the last decades of the 20th century, when epidemiological trends started to point to an impressive fall in its incidence.[27] The reason that the rates of peptic ulcer disease decreased is thought to be the development of new effective medication and acid suppressants and the discovery of the cause of the condition, H. pylori.

In the United States about 4 million people have active peptic ulcers and about 350,000 new cases are diagnosed each year. Four times as many duodenal ulcers as gastric ulcers are diagnosed. Approximately 3,000 deaths per year in the United States are due to duodenal ulcer and 3,000 to gastric ulcer.[28]

Diet as a predisposing cause

While working as a general surgeon at Holdsworthy Hospital, Mysore, India Dr Frank Tovey observed that the incidence of peptic ulcers was higher with staple diets of refined wheat flour and polished rice and much lower where the staple diets were village ground millet and pulses. Subsequently he and others have shown a mix of phospholipids and phytosterol in these diets will prevent ulcers where rats are exposed to ulcerogenic treatment with NSAIDs. They have also shown that H. pylori has a similar incidence in both populations. The combination of phospholipids and phytosterols may be of value in the prevention and treatment of duodenal ulceration and protection against the ulcerogenic effect of NSAIDs.[29]

History

John Lykoudis, a general practitioner in Greece, treated patients for peptic ulcer disease with antibiotics, beginning in 1958, long before it was commonly recognized that bacteria were a dominant cause for the disease.[30]

Helicobacter pylori was rediscovered in 1982 by two Australian scientists, Robin Warren and Barry J. Marshall as a causative factor for ulcers.[31] In their original paper, Warren and Marshall contended that most gastric ulcers and gastritis were caused by colonization with this bacterium, not by stress or spicy food as had been assumed before.[32]

The H. pylori hypothesis was poorly received,[33] so in an act of self-experimentation Marshall drank a Petri dish containing a culture of organisms extracted from a patient and five days later developed gastritis. His symptoms disappeared after two weeks, but he took antibiotics to kill the remaining bacteria at the urging of his wife, since halitosis is one of the symptoms of infection.[34] This experiment was published in 1984 in the Australian Medical Journal and is among the most cited articles from the journal.

In 1997, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with other government agencies, academic institutions, and industry, launched a national education campaign to inform health care providers and consumers about the link between H. pylori and ulcers. This campaign reinforced the news that ulcers are a curable infection, and that health can be greatly improved and money saved by disseminating information about H. pylori.[35]

In 2005, the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Dr. Marshall and his long-time collaborator Dr. Warren "for their discovery of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease." Professor Marshall continues research related to H. pylori and runs a molecular biology lab at UWA in Perth, Western Australia.

Some believed that mastic gum, a tree resin extract, actively eliminates the H. pylori bacteria.[36] However, multiple subsequent studies have found no effect of using mastic gum on reducing H. pylori levels.[37][38]

Notes

- ^ Kurata 1997 explains that "Data in Fig. 8 indicate that 89% of all serious upper GI disease can be accounted for by NSAIDs and H. pylori, with cigarette smoking acting as a synergistic co-factor."(14)

- ^ Sonnenberg in his study cautiously concludes that, among other potential factors that were found to correlate to ulcer healing, "moderate alcohol intake might [also] favor ulcer healing." (p. 1066)

References

- ^ "GI Consult: Perforated Peptic Ulcer". Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ "Peptic ulcer".

- ^ a b c d "Peptic Ulcer". Home Health Handbook for Patients & Caregivers. Merck Manuals. October 2006.

- ^ "Peptic ulcer". Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ "Ulcer Disease Facts and Myths". Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ Cullen DJ, Hawkey GM, Greenwood DC, et al. (1997). "Peptic ulcer bleeding in the elderly: relative roles of Helicobacter pylori and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs". Gut. 41 (4): 459–62. doi:10.1136/gut.41.4.459. PMC 1891536. PMID 9391242.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.humpath.com/spip.php?article7501

- ^ Ma LS A Tribute to Dr Frank I Tovey on his 90th Birthday World J Gastroentol 2011 August 21: 17(31):3565–3566

- ^ Johannessen T. "Peptic ulcer disease". Pasienthandboka.

- ^ Kato, Ikuko (1992). "A Prospective Study of Gastric and Duodenal Ulcer and Its Relation to Smoking, Alcohol, and Diet". American Journal of Epidemiology. 135 (5): 521–530. PMID 1570818.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Salih, Barik (June 2007). "H pylori infection and other risk factors associated with peptic ulcers in Turkish patients: A retrospective study". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (23): 3245–8. PMID 17589905.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Martin, U.S.A.F.M.C. (Major), David F. (28 June 2008). "Campylobacter pylori, NSAIDS, and Smoking: Risk Factors for Peptic Ulcer Disease". American Journal of Gastroenterology. 84 (10): 1268–72. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1989.tb06166.x. PMID 2801677. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)[dead link] - ^ Kurata Ph.D., M.P.H., John H. (January 1997). "Meta-analysis of Risk Factors for Peptic Ulcer: Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs, Helicobacter pylori, and Smoking". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 24 (1): 2–17. doi:10.1097/00004836-199701000-00002. PMID 9013343.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ For nearly 100 years, scientists and doctors thought that ulcers were caused by stress, spicy food, and alcohol. Treatment involved bed rest and a bland diet. Later, researchers added stomach acid to the list of causes and began treating ulcers with antacids. National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse

- ^ Ryan-Harshman, M (2004 May). "How diet and lifestyle affect duodenal ulcers. Review of the evidence". Canadian family physician Medecin de famille canadien. 50: 727–32. PMID 15171675.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pennsylvania, Editors, Raphael Rubin, M.D., Professor of Pathology, David S. Strayer, M.D., Ph.D., Professor of Pathology, Department of Pathology and Cell Biology, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University Philadelphia, Pennsylvania ; Founder and Consulting Editor, Emanuel Rubin, M.D., Gonzalo Aponte Distinguished Professor of Pathology, Chairman Emeritus of the Department of Pathology and Cell Biology, Jefferson Medical College of Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia,. Rubin's pathology : clinicopathologic foundations of medicine (Sixth Edition. ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 623. ISBN 978-1605479682.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ A, Sonnenberg (1981). "Predictors of duodenal ulcer healing and relapse". Journal of Gastroenterology. 81 (6): 1061–7. PMID 7026344.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Peptic ulcer". Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ "Tests and diagnosis". Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ "ATLAS OF PATHOLOGY". Retrieved 26 August 2007.

- ^ "PEPTO-BISMOL ORIGINAL LIQUID". PEPTO-BISMOL. PROCTOR AND GAMBLE. Retrieved 10 September 2011.

- ^ "Ranitidine in Peptic Ulcer".

- ^ "Sucralfate for Peptic Ulcer".

- ^ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. Retrieved Nov. 11, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Snowden FM (2008). "Emerging and reemerging diseases: a historical perspective". Immunol. Rev. 225 (1): 9–26. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00677.x. PMID 18837773.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Brown LM (2000). "Helicobacter pylori: epidemiology and routes of transmission". Epidemiol. Rev. 22 (2): 283–97. PMID 11218379.

- ^ "Peptic ulcer disease". Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- ^ Kurata JH, Haile BM (1984). "Epidemiology of peptic ulcer disease". Clin Gastroenterol. 13 (2): 289–307. PMID 6378441.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Ma LS. A tribute to Dr. Frank I Tovey on his 90th birthday World J Gastroenterol. 2011 August 21; 17(31): 3565-3566.

- ^ Rigas, Basil; Papavasassiliou, Efstathios D. (22 May 2002). "Ch. 7 John Lykoudis. The general practitioner in Greece who in 1958 discovered the etiology of, and a treatment for, peptic ulcer disease.". In Marshall, Barry J. (ed.). Helicobacter pioneers: firsthand accounts from the scientists who discovered helicobacters, 1892–1982. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 74–88. ISBN 978-0-86793-035-1.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - ^ Marshall B.J. (1983). "Unidentified curved bacillus on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis". Lancet. 1 (8336): 1273–75. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(83)92719-8. PMID 6134060.

- ^ Marshall B.J., Warren J.R. (1984). "Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration". Lancet. 1 (8390): 1311–15. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91816-6. PMID 6145023.

- ^ Kathryn Schulz (9 September 2010). "Stress Doesn't Cause Ulcers! Or, How To Win a Nobel Prize in One Easy Lesson: Barry Marshall on Being ... Right". The Wrong Stuff. Slate. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ^ Van Der Weyden MB, Armstrong RM, Gregory AT (2005). "The 2005 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine". Med. J. Aust. 183 (11–12): 612–4. PMID 16336147.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ulcer, Diagnosis and Treatment - CDC Bacterial, Mycotic Diseases

- ^ Huwez FU, Thirlwell D, Cockayne A, Ala'Aldeen DA (1998). "Mastic gum kills Helicobacter pylori [Letter to the editor, not a peer-reviewed scientific article]". N. Engl. J. Med. 339 (26): 1946. doi:10.1056/NEJM199812243392618. PMID 9874617. Retrieved 6 September 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) See also their corrections in the next volume. - ^ Loughlin MF, Ala'Aldeen DA, Jenks PJ (2003). "Monotherapy with mastic does not eradicate Helicobacter pylori infection from mice". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51 (2): 367–71. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg057. PMID 12562704.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bebb JR, Bailey-Flitter N, Ala'Aldeen D, Atherton JC (2003). "Mastic gum has no effect on Helicobacter pylori load in vivo". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52 (3): 522–3. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg366. PMID 12888582.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

Radiology and Endoscopy from MedPix