Captive orcas

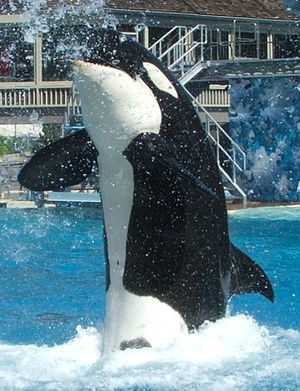

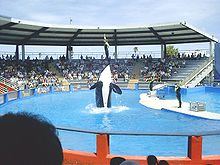

Dozens of orcas (killer whales) are held in captivity for breeding or performance purposes. The practice of capturing and displaying orcas in exhibitions began in the 1960s, and they soon became popular attractions at public aquariums and aquatic theme parks due to their intelligence, trainability, striking appearance, playfulness, and sheer size. As of 24 March 2024, around 55 orcas are in captivity worldwide, 33 of which were captive-born.[1][2] At that time, there were 18 orcas in the SeaWorld parks.[3]

The practice of keeping orcas in captivity is controversial, due to their separation from their familial pod during capture, and their living conditions and health in captivity.[4] Additionally, concerns have been raised regarding the safety of animal trainers entering the water to work with captive orcas, which have been responsible for numerous attacks on humans—some fatal. Attacks on humans by wild orcas are rare, and no fatal ones have been reported.

Orcas

[edit]Orcas are large, active and intelligent. Males range from 6 to 9.7 m (20 to 32 ft) and can weigh over 8 tonnes (8.8 tons), while females range from 5 to 7 m (16 to 23 ft) and weigh 3 to 5 tonnes (3.3 to 5.5 tons).[5] The orca is the largest species of the dolphin family. The species is found in all the world's oceans, from the frigid Arctic and Antarctic regions to warm, tropical seas. Orcas are intelligent, versatile and opportunistic predators. Some populations feed entirely on fish, while others hunt marine mammals, including sea lions, elephant seals, seals, walruses, porpoises, dolphins, large whales and some species of shark, including great whites. The species is an apex predator, as no other animal predates on orcas. There are up to five distinct orca types, some of which may be separate races, subspecies or species.[6] Orcas are highly social, and some populations are composed of matrilineal family groups that are the most stable of any animal species.[7] The sophisticated social behaviour, hunting techniques, and vocal behaviour of orcas have been described as manifestations of animal culture.[8]

Although the orca is not an endangered species, some populations are threatened or endangered due to bioaccumulation of persistent organic pollutants, depletion of prey populations, captures for marine mammal parks, conflicts with fishing activities, acoustic pollution, shipping vessels, stress from whale-watching boats, and habitat loss.[9][10][11]

Capture and breeding

[edit]North Eastern Pacific captures

[edit]

The first capture in the North Eastern Pacific occurred in November 1961. An orca of the Pacific offshore ecotype,[12] suspected to be ailing by Marineland of the Pacific officials,[13] was netted by its collecting crew when swimming alone near Newport Beach, California. They took the 5.2 m (17 ft) orca to a tank at the aquarium.[14] She became known as Wanda, but convulsed and died two days later after "swimming at high speed around the tank, striking her body repeatedly", recalled Marineland's Frank Brocato.[15] The next orca captured, Moby Doll, was harpooned in 1964[16] but survived for nearly three months in captivity when taken to Vancouver, British Columbia, by the Vancouver Aquarium.[17] He was a member of J Pod of the Southern Resident Killer Whales,[18] the population of killer whales most damaged by subsequent captures.[19]

The third capture for display occurred in June 1965 when a fisherman found a 22-foot (6.7 m) male orca in his floating salmon net that had drifted close to shore near Namu, British Columbia. The killer whale was sold for $8,000 to Ted Griffin, a Seattle public aquarium owner. Named after his place of capture, Namu was the subject of a film that changed some people's attitudes toward orcas.[20]

A few months later, Griffin procured a companion for Namu: a very young, 14 foot (4.25 m), 2000 lb (900 kg) orca captured off Whidbey Island, Puget Sound, Washington.[21][22][23] Shamu means 'Friend of Namu'[24] (alternately 'She-Namu').[25] However, Shamu did not get along with Namu and so was sold to SeaWorld in San Diego in December 1965.[26][27]

The Yukon Harbor operation was the first planned, deliberate capture of multiple orcas. After a long and dramatic 17-day operation in February and March 1967, five southern resident orcas were taken into captivity, while three others died entangled in nets.[28][29]

During the 1960s and early 1970s, nearly 50 orcas were taken from Pacific waters for exhibition. The Southern Resident community of orcas in the Northeast Pacific lost 48 of its members to captivity. By 1976, only 80 orcas were left in the community, which remains endangered. With subsequent captures, the theme parks learned more about avoiding injury during capture and subsequent care of orcas. In addition, animal trainers developed techniques to work with orcas, whose performances and tricks made them a great attraction to visitors. As commercial demand increased, growing numbers of Pacific orcas were captured, peaking in 1970.[30]

A turning point came with a mass capture of orcas from the L-25 pod on August 8, 1970 at Penn Cove in Puget Sound off the coast of Washington. The Penn Cove capture became controversial due to the large number of wild orcas that were taken (seven) and the number of deaths that resulted: four juveniles died, as well as one adult female who drowned when she became tangled in a net while attempting to reach her calf. In his interview for the CNN documentary Blackfish, former diver John Crowe told how all five of the orcas had their abdomens slit open and filled with rocks, their tails weighted down with anchors and chains, in an attempt to conceal the deaths.[31] The facts surrounding their deaths were discovered three months later after three carcasses washed ashore on Whidbey Island. Public concern about the welfare of the animals and the effect of captures on the wild pods led to the Marine Mammal Protection Act being passed in 1972 by the US Congress, protecting orcas from being harassed or killed, and requiring special permits for capture. Since then, few wild orcas have been captured in Northeastern Pacific waters.[32][33]

Lolita, originally known as Tokitae, was a survivor of the Penn Cove captures. She was about four years old at time of capture and was the second oldest captive orca at the time of her death in August 2023. Lolita is the subject of the documentary Lolita: Slave to Entertainment, released in 2008.[34] Various groups argued that Lolita should be released into the wild.[35][36] Lolita's mother, L-25 (also known as Ocean Sun), is still alive at approximately 90 years old and is the oldest living southern resident orca in the wild.[37][38]

Icelandic captures

[edit]

When the US Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 effectively stopped the capture of Pacific orcas, exhibitors found an area more tolerant of killer whale captures in Iceland. Icelandic herring fishermen had traditionally seen orcas as competitors for their catch, and sale of live killer whales promised a large new source of income. 48 orcas captured in Icelandic waters were exported to marine parks between 1976 and 1988. The capture process was based on luring the orcas by dumping leftovers from herring fishing in front of the pod, capturing the orcas in a purse seine net, selecting desirable animals and hauling them on board in a specially designed frame, then placing them in foam-lined boxes full of seawater.[39] However, restrictions on US Orca import permits and advances in captive breeding programs meant that the market never became as large as expected. Growing concern from conservationists and animal rights activists has caused the Icelandic government to limit the number of orcas that may be captured each year.[40]

The Icelandic captives included Keiko, caught in 1979 and sold to the Icelandic aquarium in Hafnarfjörður. Three years later, he was sold to Marineland of Canada, where he first started performing for the public and developed skin lesions indicative of poor health. He was then sold to Reino Aventura (now named Six Flags México), an amusement park in Mexico City, in 1985. He was the star of the 1993 movie Free Willy, the publicity from which led to an effort by Warner Brothers Studio to find him a better home. Using donations from the studio, Craig McCaw from the Oregon Coast Aquarium spent over $7 million to construct facilities to return him to health with the hope of returning him to the wild. He was airlifted to his new home in January 1996, where he soon regained weight. In September 1998, he was flown to Klettsvik Bay in Vestmannaeyjar in Iceland, and gradually reintroduced to the wild, returning to the open sea on July 11, 2002. Keiko died from pneumonia on December 12, 2003, at the age of 27 years.[41][42] He had become lethargic and had a loss of appetite.

North Western Pacific captures

[edit]1,477 killer whales were hunted in Japanese waters between 1948 and 1972, 545 of them around Hokkaido. Killer whale encounters in Japanese waters are now rare.[43] In 1997 a group of ten killer whales was corralled by Japanese fisherman banging on iron rods and using water bombs to disorient the animals and force them into a bay near Taiji, Wakayama, a technique known as dolphin drive hunting which these villagers have been practising for years. The orcas were held in the bay for two days before being auctioned to Japanese marine parks. Five animals were released, and the other five transported via road or sea to the aquariums. All five are now dead.[44]

The first live killer whale captured in Russia was an 18-foot (5.5 m)-long female estimated to be about six years old, captured off the Pacific coast of the Kamchatka district on September 26, 2003. She was transferred over 7,000 miles (11,000 km) to a facility owned by the Utrish Dolphinarium on the Black Sea, where she died in October 2003 after less than a month in captivity.[45]

Killer whales born in captivity

[edit]The majority of today's theme-park orcas were born in captivity: 33 out of 56. Kalina, a female orca born in September 1985 at SeaWorld Orlando, was the first captive orca calf to survive more than two months. Her mother, Katina, was captured near Iceland, and her father, Winston (also known as Ramu III), was a Pacific Southern Resident, making Kalina an Atlantic/Pacific hybrid—a situation that would not have occurred in the wild.[46]

The first orca conceived through artificial insemination was a male named Nakai, who was born to Kasatka and father Tilikum at the SeaWorld park in San Diego in September 2001.[47] A female killer whale named Kohana, the second orca conceived in this manner, was born at the same park eight months later.[48] Artificial insemination lets park owners maintain a healthier genetic mix in the small groups of orcas at each park while avoiding the stress of moving the animals between marinas.[49]

The practice of exhibiting orcas born in captivity is less controversial than of retaining free-born orcas, since the captive-born orcas have known no other world and may not be able to adapt to life in the wild. Captive breeding also promises to reduce incentives to capture wild orcas.[50] However, in January 2002 the Miami Seaquarium stated that captive orcas are dying faster than they are being born, and as it is virtually impossible to obtain orcas captured from the wild, the business of exhibiting captive orcas may eventually disappear.[51]

Captivity locations

[edit]

As of September 29, 2016, orcas in 13 facilities in North and South America, Europe and Asia provide entertainment for theme park visitors.[52] Building the physical infrastructure of the parks requires major capital expenditure, but as the star attractions the orcas are arguably the most valuable and irreplaceable assets.

SeaWorld

[edit]SeaWorld is a chain of marine mammal parks in the United States and is the largest owner of captive killer whales in the world. The parks feature killer whale, sea lion, and dolphin shows and zoological displays featuring various other marine animals. The parks' icon is Shamu, the orca.[53] Parks include:

- SeaWorld San Diego, San Diego, California; home of Corky II, Orkid, Ulises, Kalia, Ikaika, Keet, Shouka and Makani. Corky II is the oldest killer whale ever kept in human care, estimated to be 58 years old.

- SeaWorld Orlando, Orlando, Florida; home of Katina, Trua, Nalani, Malia, and Makaio

- SeaWorld San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas; home of Kyuquot, Tuar, Takara, Sakari, and Kamea

SeaWorld Ohio closed in 2001.

Miami Seaquarium

[edit]The Miami Seaquarium is an aquarium located on Virginia Key in Biscayne Bay near downtown Miami, Florida. Currently owned by The Dolphin Company,[54][55] the Seaquarium was the first major marine park attraction in South Florida, opening in 1955. In addition to marine mammals, it houses fish, sharks, sea turtles, birds and reptiles.[56] It was home to Lolita (aka Tokitae), who was expected to be returned in 2024 to her natal waters in the Pacific Northwest and reside in a semi-wild sea-pen in the Salish Sea for the remainder of her life.[57][55][58] However, she died on August 18, 2023.[59]

Marineland Canada

[edit]Marineland was the last facility in Canada to hold a captive orca. It is a privately held themed amusement and animal exhibition park in the city of Niagara Falls, Ontario, and one of the main tourist destinations in town.[60] The last orca held there was Kiska, who died of a bacterial infection on March 9, 2023, ending orca captivity in Canada.

A law banning breeding or keeping cetaceans in captivity (except for rehabilitation or research, and those already held) was passed by the Parliament of Canada in June 2019. During the debate, the Vancouver Aquarium, the only other Canadian facility still holding cetaceans, announced it would no longer keep dolphins or whales.[61][62]

Marineland (Antibes)

[edit]Marineland is an animal exhibition park in Antibes, France, founded in 1970. It receives more than 750,000 visitors per year, and is the only French facility to house orcas.[63] The park is a subsidiary of Parques Reunidos, a Spanish group with properties in Europe, Argentina and the United States. It currently holds Wikie, born at the park in 2001, and her son Keijo, born in 2013. Moana, who was born at the park in 2011, died in October of 2023. In March 2024, Inouk, a 25-year old male and Wikie's brother, died.[64] With only two orcas remaining at the park and the French government having enacted a law banning the public display of cetaceans starting in 2026, the future of Marineland's orca exhibit is in doubt. Marineland has reportedly been considering transferring its remaining orcas to Japan, although French authorities have stated that no export permit applications had yet been submitted by the park.[65]

Loro Parque

[edit]Loro Parque (Spanish for "parrot park") is a zoo located on the outskirts of Puerto de la Cruz on Tenerife, Spain. The park has the world's largest indoor penguin exhibition, the longest shark tunnel in Europe, and is one of only two parks in Europe to house killer whales.[66]

In February 2006, Loro Parque received four young killer whales; two males, Keto (1995-2024) and Tekoa (born in 2000), and two females, Kohana (2002-2022) and Skyla (2004-2021) on loan from SeaWorld. Sea World sent its own professionals, including trainers, curators & veterinarians, to supplement the staff at Loro Parque. In 2004 and 2005, before the killer whales were brought to Loro Parque, eight animal trainers from the park were sent to Sea World parks in Texas and Florida for training. However, only half of these trainers are currently employed in Orca Ocean, Loro Parque's facility for the killer whales. None of the subsequent employees hired have been sent to Sea World parks for training.[67] On December 24, 2009, orca trainer Alexis Martinez, age 29, was killed during a Christmas show rehearsal when he was attacked by Keto, which resulted in his drowning. He had worked at Loro Parque since 2004. From this date the trainers no longer enter the water with the orcas during live shows. In December 2017, SeaWorld announced that the orcas they had loaned to Loro Parque now belonged to the Spanish amusement park.

Male orca Adán, the inbred son of Kohana and Keto, and female orca Morgan also live at Loro Parque. Morgan was rescued in 2010 and arrived at the facility in 2011, while Adán was born there in 2010. Adán's sister, Victoria (Vicky), was born in 2012, but died in 2013.[68] In 2018, Morgan gave birth to her first calf, female orca Ula. Skyla died on March 11, 2021, Ula died on August 10, 2021, Kohana died on September 14, 2022 and Keto died on November 22, 2024.[citation needed]

Mundo Marino

[edit]Mundo Marino, located south of Buenos Aires in the coastal town of San Clemente del Tuyú, Argentina, is the largest aquarium in South America. Mundo Marino is home to one male killer whale, Kshamenk, who stranded or was force-stranded in 1992.[69] Kshamenk is estimated to have been around 4+1⁄2 years old when he arrived.

Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium

[edit]Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium is a public aquarium in Minato-ku, Nagoya, Aichi Prefecture, Japan. The Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium is the largest existing public aquarium in Japan. Orcas have been housed in Japan's largest main show tank of 13,500,000 litres (3,566,000 US gal) since 2003. Captivity began with Kū/Ku,[70] followed by Nami,[71] Stella, Bingo, and Ran II, and on November 13, 2012, Bingo and Stella's female calf, Lynn, was born. Port of Nagoya Public Aquarium is currently home to Lynn, and Earth.[72]

Kamogawa Sea World

[edit]Kamogawa Sea World is an aquarium located in Kamogawa, Chiba Prefecture, Japan. In 1970, the facility first started breeding killer whales in Japan, and in 1998, Stella succeeded in giving birth and received a breeding award from JAZA[73](Maggie gave birth to the aquarium's first calves, but none survived). Currently, Lovey (F), Lara (F), Ran II (F) and Luna (F) are housed there.[74]

Chimelong Spaceship

[edit]Chimelong Spaceship is a marine park located in Hengqin, Zhuhai, Guangdong, China. In 2017, the facility opened an orca breeding facility, initially containing five males and four females sourced from Russia.[75] They currently house 14 orcas: five females (Sonya, Nukka / Grace, Jade, Katenka and Katniss), and eight males (Tyson, Nakhod, Bandhu, Kaixin, Chad, Yīlóng, Loki and Wulong) and one unknown gender calf at Chimelong Holding Facility who was expected to be born between September to December 2023.

Other marine exhibitions

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2023) |

- Moskvarium, Moscow, Russia; home of Naja/Naya

- Shanghai Haichang Ocean Park, Shanghai, China;[76] home of Pànghǔ, Shawn II/Sean, Dora, Cookie, Cody/Fat Beans and Dora's calf who was born in December 2023.

- SunAsia Beluga Whale World, China; home of females "Samara" and "Kyra" (real names unknown)

- Wuxi Changqiao Killer Whale Ocean World Resort, Jiangsu, China; home of two unnamed males

- Kobe Suma Sea World, Kobe, Japan; new home of Stella and Ran

- It is unknown where TIN-OO-C1306 and Malvina currently reside; they may be at a park previously listed.

Captivity conditions

[edit]Tank size and water conditions

[edit]Legal requirements for tank size vary greatly from country to country. In the US, the minimum enclosure size is set by the Code of Federal Regulations, 9 CFR 3.104, under the Specifications for the Humane Handling, Care, Treatment, and Transportation of Marine Mammals.[77] In 9 CFR 3.104, Table III classifies killer whales as Group I cetaceans with an average length of 24 feet (7.3 m). Based on length, Table I states up to two killer whales may be held in a pool with a minimum horizontal dimension (the diameter of a circular pool of water) of twice that length or 48 feet (15 m) and a minimum depth of 12 feet (3.7 m), giving a minimum volume of 21,700 cubic feet (615 m3) for two killer whales. Each additional killer whale requires a pool with an additional 10,900 cubic feet (308 m3) of volume. 9 CFR 3.104 also requires a minimum of 680 square feet (63 m2) surface area per killer whale in Table IV (the example with a cylindrical tank 48 feet (15 m) in diametre for two whales provides 905 square feet (84.1 m2) of surface area per killer whale). Swiss regulations require a larger minimum volume: 400 square metres (4,300 sq ft) × 4 metres (13 ft) deep for two killer whales, or 1,600 cubic metres (57,000 cu ft). The Alliance of Marine Mammal Parks and Aquariums (AMMPA) goes further, and recommends 1,918 cubic metres (67,700 cu ft) for two killer whales.[78] The US exhibitors of captive killer whales belong to the AMMPA, but exhibitors in other countries do not.[79]

The Miami Seaquarium has been criticised for the small size of the tank holding their sole killer whale, Lolita, which is less than two of her body lengths wide at any point.[80] The tank used by Marineland of Canada for Kiska was an estimated 40 metres (130 ft) x 20 metres (66 ft) wide. Kiska would complete 879 laps around her tank every day which was a total distance of about 100 km, the minimum distance most wild orca pods travel daily. Kiska developed ritualistic, repetitive behaviours (such as repeatedly rubbing her skin against the tank until injured, thrashing, and floating motionless in one spot) that indicate stress and are abnormal for wild orcas.[81]

Nutrition and medical care

[edit]On average, an adult killer whale in the wild may eat about three to four percent of their body weight daily,[82] or as much as 227 kg (500 lb) of food for a six-ton male. Their diet in the wild depends on what is available, and may include fish, walruses, seals, sea lions, penguins, squid, sea turtles, sharks and whales.[83] According to SeaWorld, each of their adult orcas receives 140 to 240 pounds of food per day, primarily herring, capelin, salmon and mackerel. To maintain their alertness, the killer whales are fed at sporadic intervals throughout the day (as would happen in the wild) and feeding is often combined with training and shows. Each batch of fish is carefully tested to determine its nutritive composition, and each killer whale's weight, activity and health is carefully monitored to determine any special dietary requirements.[84]

Killer whales have been the subject of extensive medical research since their first capture, and much is known about prevention and treatment of the common viral and bacterial infections, including vaccination and use of antibiotics and other medicines.[85] Allometric principles and therapeutic drug monitoring are used to accurately determine the doses and avoid toxicity.[86]

Training

[edit]Whales are trained using positive reinforcement; usually by giving the killer whale food when they perform the desired tasks. If the animal is unsuccessful, it is asked again. Food withdrawal is only used in facilities considered to be improper. Food rewards are often called "least rewarding scenarios" as many whales find fish boring or are simply not hungry.[87] Secondary reinforcement—things not essential to life, such as play time, tactile rewards and fun games—can also be used as rewards.[88]

Issues with captivity

[edit]The practice of keeping killer whales in captivity is controversial, and organisations such as World Animal Protection, PETA, and the Whale and Dolphin Conservation campaign against the captivity of killer whales. Orcas in captivity may develop physical pathologies, such as the dorsal fin collapse seen in 80–90% of captive males.

The captive environment bears little resemblance to their wild habitat, and the social groups that the killer whales are put into are foreign to those found in the wild.[4] Captive orcas are kept in small tanks, false social groupings and chemically altered water. Captive killer whales have been observed acting aggressively toward themselves, other killer whales, or humans, which is a result of stress.[89]

Disease and lifespan

[edit]The lifespan of killer whales in captivity versus wild killer whales is disputed. Several studies published in scientific journals show that the average mortality rate for captive killer whales is approximately three times higher than in the wild.[90] A 2015 study in the Journal of Mammalogy, authored by SeaWorld's vice-president of theriogenology, Todd Robeck,[91][92] concluded that the life expectancy for killer whales born at SeaWorld is the same as those in the wild.[93] In the wild, female killer whales have a typical lifespan of 60–80 years, and a maximum recorded lifespan of 103 years.[94] The average lifespan for males in the wild is 30 years, but some live up to 50–60 years.[95] The 2015 study has been criticised by Trevor Willis, senior lecturer in marine biology at the University of Portsmouth, who stated that the study is misleading, "clearly wrong" and indicative of "poor practice". He stated that it is misleading in two ways: "First, it compares two completely different circumstances: the controlled environment of a swimming pool, with highly trained vets on hand; and the wild ocean. "There are no predators in a swimming pool. Second, and in the absence of any other information, it appears they've looked at the survival rate of calves in the first two years of life and extrapolated it out 50 years into the future." He also stated that no captive orca has lived for 55.8 years,[91] the recorded average life expectancy of adult orcas at SeaWorld.[92]

SeaWorld San Antonio's 14-year-old Taku, born in captivity, died suddenly on October 17, 2007. Trainers were notified that Taku had been acting differently a week before his death. The necropsy determined that Taku had died from a sudden case of pneumonia, a common illness among captive orcas.[96][97] It was also discovered that Taku was infected by the West nile virus, transmitted by mosquitos.[98]

The shallowness of orca tanks forces orcas to spend a lot of time at the surface, where they are exposed to ultraviolet (UV) rays. Sunburns and the development of cataracts in orcas in captivity are attributed to this exposure. Orcas in the wild live at higher latitudes, meaning less intense sun, and spend more time in deeper, darker waters.[99] While the effects of prolonged UV exposure on orcas' skin is uncertain, since captive orca necropsies are extremely secretive,[100] it is thought that prolonged exposure to UV rays on unprotected skin would have the same negative effects such as melanoma (skin cancer) on orcas as it does on humans.[citation needed]

The original Namu developed a bacterial infection which damaged his nervous system, causing him to become unresponsive to people. During his illness he charged full-speed into the wire mesh of his pen, thrashed violently for a few minutes and then died.[101]

Dorsal fin collapse

[edit]

Most captive male killer whales, and some females, have a dorsal fin that is partially or completely collapsed to one side. Several hypotheses exist as to why this happens. A dorsal fin is held erect by collagen, which normally hardens in late adolescence.

Scientists from the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) have reported that "the collapsed dorsal fins commonly seen in captive killer whales do not result from a pathogenic condition, but are instead thought to most likely originate from an irreversible structural change in the fin's collagen over time. Possible explanations for this include: (1) alterations in water balance caused by the stresses of captivity dietary changes, (2) lowered blood pressure due to reduced activity patterns, or (3) overheating of the collagen brought on by greater exposure of the fin to the ambient air."[102] According to SeaWorld's website, another reason for the fin to bend may be the greater amount of time that captive whales spend at the surface, where the fin is not supported by water pressure.[103] The Whale and Dolphin Conservation says that dorsal fin collapse is largely explained by captive killer whales swimming in small circles due to the inadequate space in which they have to swim.[104]

Collapsed or collapsing dorsal fins are rare in most wild populations and usually result from a serious injury to the fin, such as from being shot or colliding with a vessel.[102] After exposure to the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, two male resident killer whales experienced dorsal fin collapse, and the animals subsequently died. In 2002, the dorsal fin of a stranded killer whale showed signs of collapse after three days but regained its natural upright appearance as soon as the orca resumed strong normal swimming upon release.[102]

A study in 1998 recorded that 7 out of 30 (23%) adult male killer whales off the coast of New Zealand had abnormal dorsal fins. Fins were considered abnormal if they displayed collapse, partial collapse, or bends.[105] This is a higher prevalence of these deformities than in other areas of the world, as studies have reported rates of abnormal fins in wild adult males at 4.7% in British Columbia and 0.57% in Norway.[105] Researchers in 1994 found that of the ~300 killer whales photographed off the coast of British Columbia, fewer than 1% were observed to have "droopy" dorsal fins.[106]

Attacks on humans

[edit]ABC News reported that captive killer whales have attacked nearly two dozen people since the 1970s.[107] Studies of killer whales in the wild have identified at least two categories, based on their territorial range. Those living in a limited area, such as Puget Sound or the Strait of Juan de Fuca, are termed "resident" whales, while "transient" whales roam the oceans at will. These "transient" types have to be more aggressive, in order to assert themselves in a wide range of territories and to prey on a variety of different species. This increased aggressiveness does not disappear in captivity.[108] Furthermore, captivity itself has been asserted to aggravate aggressive behavior, resulting in a "cetacean equivalent of anxiety disorder".[109]

Captive killer whale attacks on humans fall mostly into the categories of biting during feeding, ramming in the water, and holding under water. Killer whales biting trainers during feeding or shows is generally the mildest form of attack seen, but can escalate to an animal dragging the trainer underwater and holding them there until they lose consciousness or drown. Trainers who have had killer whales ram into them in the water have suffered from injuries including internal bleeding, broken bones, ruptured organs, and heart attack.[110]

Tilikum, a large bull male killer whale who died in early 2017, was involved in the death of three individuals since his capture near Iceland in November 1983. In 1991, Tilikum and two other killer whales grabbed 20-year-old trainer Keltie Byrne in their mouths and tossed her to each other, drowning Byrne.[111] On July 5, 1999, Daniel P. Dukes visited SeaWorld and stayed after the park closed, evading security so as to enter a killer whale tank.[112] He was found dead the next day, floating in Tilikum's pool. He died due to a combination of hypothermia,[dubious – discuss] trauma, and drowning but Dukes was covered in bruises, abrasions and bite marks, and his scrotum had been ripped open,[113] indicating that Tilikum had toyed with the victim. It is unclear whether Tilikum actually caused the man's death.[114] On February 24, 2010, after a noontime performance at Sea World, Orlando, Florida, Tilikum killed trainer Dawn Brancheau during a training session with the whale.[115] This latest incident with Tilikum reawakened a heated discussion about the effect of captivity on the killer whale's behavior.[116] In May 2012, Occupational Safety and Health Administration administrative law judge Ken Welsch faulted SeaWorld for the death of Dawn Brancheau and introduced regulations requiring a physical barrier between trainers and killer whales.[117]

Kasatka, a female killer whale who was captured off the coast of Iceland in October 1978 at the age of one year, has shown aggression toward humans. Kasatka tried to bite a trainer during a show in 1993, and again in 1999.[118] On November 30, 2006, Kasatka grabbed a trainer and dragged him underwater during their show. The trainer suffered puncture wounds to both feet and a torn metatarsal ligament in his left foot.[119][120][121]

On Christmas Eve of 2009, 29-year-old Alexis Martínez of Loro Parque, Tenerife, Spain, was killed by a whale named Keto. After spending two and a half minutes at the bottom of the 12-meter-deep main pool, his body was retrieved but he could not be revived. The park initially characterized the death as an accident and claimed that the body showed no signs of violence, but the subsequent autopsy report stated that Martinez died due to grave injuries sustained by an orca attack, including multiple compression fractures, tears to vital organs, and the bite marks of the animal on his body.[122] During the investigation into Martinez's death, it came to light that the park had also misrepresented a 2007 incident with Tekoa, the other male, claiming that it was an accident rather than an attack.[123]

The only recorded injury of a human by an orca in the wild happened in 1972 at Point Sur, California.[124]

Aggression between captive orcas

[edit]In August 1989, the dominant female Icelandic killer whale at SeaWorld San Diego, Kandu V, attempted to "rake" a female newcomer named Corky. Raking is a way orcas show dominance by forcefully scratching at another with their teeth (however, raking can also be a way of communication or play between whales, and it is witnessed in the wild). Kandu charged at Corky, attempting to rake her, missed, and continued her charge into the back pool, where she ended up ramming the wall, rupturing an artery in her jaw. The crowd was quickly ushered out of the stadium. Forty-five minutes later Kandu V sank to the bottom of the pool and died.[125]

Kanduke, a male captured from T pod in British Columbia, Canada, in August 1975, often fought with a younger Icelandic male named Kotar. The aggression became increasingly serious, leading to an incident in which Kotar bit a part of Kanduke's genitals and caused an infection. It is not known if such serious aggression and injury would occur in the open seas.[126]

Early pregnancy and related issues

[edit]Captive killer whales often give birth at a much younger age than in the wild, sometimes as young as age seven. The young mothers may have difficulty raising their offspring. The calves have a relatively low survival rate, though some have lived into adulthood.

Corky (II), a female from the A5 Pod in British Columbia, Canada became the first killer whale to become pregnant in captivity, giving birth on February 28, 1977. The calf died after 18 days. Corky went on to give birth six more times, but the longest surviving calf, Kiva, lived only 47 days.[127] SeaWorld has attracted criticism over its continued captivity of Corky II from the Born Free Foundation, which wants her returned to the wild.[128]

A killer whale named Katina, captured near Iceland at about three years old in October 1978, became pregnant in early spring of 1984 at SeaWorld San Diego and gave birth in September 1985 to a female named Kalina. Although ten years was an extremely young age for a killer whale to become a mother, Kalina was the first killer whale calf to be successfully born and raised in captivity.[129] In turn, Kalina gave birth at only seven and a half years of age to her first calf, a male named Keet.[46]

Gudrun was an Icelandic female caught in the 1970s. In 1993, she gave birth to Nyar, a female who was both mentally and physically ill, and who Gudrun tried to drown during several shows. Nyar died from an illness a few months later. Gudrun died in 1996 from stillbirth complications.[130][131]

Taima is a transient/Icelandic hybrid female killer whale born in captivity to Gudrun in 1989.[132] Trainers believe that Gudrun's behavior towards Nyar may have confused Taima, as she may have learned by example that this was how to raise a calf. In May 1998, Taima gave birth to a male calf named Sumar. They were separated when he was about eight months old because of the aggression between them. On one occasion while performing, Taima started biting Sumar and throwing him out of the pool onto the trainer's platform. She then slid out herself, and continued to bite him. In November 2000, Taima gave birth to a male named Tekoa. The two were separated after only nine months due to aggression between them.[133][134] On March 12, 2007, Taima gave birth to her third calf, Malia. Taima seemed to be a better mother this time, and no notable occurrences of aggression were reported; this may be in part due to the fact that Kalina acted as "aunt" to Malia and helped Taima to look after her. Kalina was a very experienced mother and was often kept with Malia, while Taima was given time with her mate, Tilikum. Taima died in 2010 during the birthing process of her fourth calf. The calf, fathered by Tilikum, was stillborn.

Kayla, a killer whale born in captivity, gave birth to her first calf on October 9, 2005, a female named Halyn. Kayla rejected her calf, perhaps because she had never been exposed to a young calf before and did not know how to deal with it. Halyn was moved to a special animal care facility to be hand raised. Halyn died unexpectedly on June 15, 2008.[135]

On October 13, 2010, Kohana, an eight-year-old female killer whale, gave birth to a male calf at Loro Parque's "Orca Ocean" exhibit after a four-hour labor. The calf weighed about 150 kilograms (330 lb), and was two meters (6 ft 7 in) long. Kohana has yet to establish a "maternal bond" with her calf, forcing trainers to take the first steps in hand rearing him. The outcome of this pregnancy was not considered surprising, since Kohana was separated from her own mother, Takara, at three years of age, and was never able to learn about maternal care, compounded by the fact that she spent the formative years of her life surrounded by the three other juvenile killer whales at Loro Parque.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Fate of orcas in captivity". Whale & Dolphin Conservation UK. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ "Captive Orcas – Inherently Wild". Retrieved December 9, 2023.

- ^ "'Truly Amazing' 6-Year-Old Orca Whale Dies Unexpectedly at SeaWorld San Diego". Peoplemag. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ a b "Orcas in captivity". Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society. Archived from the original on August 5, 2007. Retrieved July 25, 2007.

- ^ Baird, Robin W (2002). Killer whales of the world: natural history and conservation. Stillwater, Minnesota: Voyageur Press. ISBN 0-89658-512-3.

- ^ Fisheries, NOAA. "Killer whale (Orcinus orca):: NOAA Fisheries". www.nmfs.noaa.gov. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Balcomb, C. Kenneth (2000). Killer whales: the natural history and genealogy of Orcinus orca in British Columbia and Washington State. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 0-7748-0800-4.

- ^ Glen Martin (December 1, 1993). "Killer Culture". Discover. Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- ^ "Washington Officials Say Orcas Threatened". Los Angeles Times. March 2, 2004. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "Untitled". captivekillerwhales.tumblr.com. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ Canada Dot Com. "Killer whales threatened by salmon shortage". World News Network. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ Colby, Jason M. (2018). Orca: how we came to know and love the ocean's greatest predator. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 328. ISBN 9780190673116.

- ^ "Captured Killer Whale Dies". St. Joseph Gazette. November 21, 1961. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Killer Whale Netted in Newport Harbor". Independent-Press-Telegram Newspaper of Long Beach, California / Bob Geivet. November 19, 1961. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Other Captive Orcas - Historical Chronology". PBS. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Whale to Leave For New Corral". Vancouver Sun. July 18, 1964. p. 2.

- ^ Colby, op. cit., pp. 65-66

- ^ Leiren-Young, Mark (2016). The Killer Whale Who Changed the World. Vancouver, B.C.: Greystone. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-1771643511.

- ^ Colby, op. cit., p. 3

- ^ WGBH Frontline: "Edward 'Ted' Griffin, The Life and Adventures of a Man Who Caught Killer Whales". Retrieved March 28, 2008

- ^ "The Killer in the Pool", Zimmermann, Tim, Outside, 2010 July. Retrieved 2010 July 12

- ^ "Granny's Struggle: A black and white gold rush is on", Lyke, M. L., Seattle Post-Intelligencer 2006 October 11 Retrieved 2010 July 12

- ^ "Stories Of Captive Killer Whales | A Whale Of A Business | FRONTLINE | PBS". www.pbs.org. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ "How did Shamu get her name?".

- ^ "'The Killer in the Pool': A Story that Started a Movement". July 30, 2010.

- ^ "SeaWorld Investigation: Secrets Below the Surface". KGTV San Diego. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2018.

- ^ "Shamu - Orca Aware". Orca Aware.

- ^ Colby, op. cit., pp. 103-106

- ^ "Griffin Adds Fifth Whale To Aquarium". The Seattle Times. March 6, 1967. p. 8.

- ^ Heimlich, Sara and Boran, James. Killer Whales (2001) Voyageur Press, Stillwater, Minnesota.

- ^ Aguilar, Rose. "Blackfish: Highlighting the plight of captive orcas". Aljazeera. Aljazeera Satellite Network. Retrieved November 5, 2013.

- ^ "The Capture of Orcas" In Kokomo. Retrieved February 14, 2009. Archived April 2, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Since first orca capture, views have changed". The Seattle Times. Retrieved April 1, 2022.

- ^ "Lolita's Life Today" Archived February 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Orca Network. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ "Orca survival trumps profits, 'ownership' " Archived October 4, 2011, at the Wayback Machine San Juan Journal. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Free Lolita! Bid to bring orca 'home' heats up" Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ Garrett, Howard. "Welcome to Orca Network". Welcome to Orca Network. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ "L-25 Ocean Sun". The Whale Museum. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ The Icelandic live-capture fishery for killer whales 1976–1988 Orca Home. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ^ "A Whale of a Business" PBS, Reproduced from "The Performing Orca, Why the Show Must Stop" by Erich Hoyt. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Keiko's Story: The Timeline". Keiko.com. December 12, 2003. Archived from the original on October 26, 2015. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "The Free Willy Keiko Foundation". Keiko.com. Archived from the original on May 17, 2014. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ Estes, J.A. (2007). Whales, whaling, and ocean ecosystems. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24884-7.

- ^ "More Orcas Under Threat As A Cruel Capture Is Commemorated" Archived September 8, 2012, at archive.today Orca Zone. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ "Kamchatka Orca First Victim of Russia's Captive Orca Business" Archived December 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine Humane Society International. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ a b "Kalina" Orca Spirit. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ "Artificially inseminated killer whale gives birth" BBC. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ Surprisingly, Kasatka is Kohana's grandmother."Kohana" Friend of the Orcas. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ "Artificial Insemination Produces Killer Whales" Smithsonian National Zoological Park. Retrieved February 14, 2009. Archived February 4, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Davis, Susan G. (1996). Spectacular nature : corporate culture and the Sea World experience (p72ff). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20981-7.

- ^ Free Lolita Update #52 – ACT NOW to help Lolita Archived March 11, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Orca Network. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ^ "Earth". BBC. Archived from the original on September 7, 2011.

- ^ SeaWorld Press Release Kit Archived March 7, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 5, 2007.

- ^ Ojo, Joseph (March 23, 2023). "Miami-Dade County announces Lolita the Orca will be examined by third party vets". cbsnews.com. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ a b Diaz, Johnny (March 30, 2023). "Lolita the Orca May Swim Free After Decades at Miami Seaquarium". The New York Times. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ "History of the Miami Seaquarium". Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved November 30, 2007.

- ^ Bartick, Alex (March 30, 2023). "Captured Southern Resident orca Lolita to return to Puget Sound after more than 50 years". komonews.com. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ Lolita's Life Today Archived February 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ "Lolita, beloved killer whale who had been in captivity, has died, Miami Seaquarium says". CBS News. August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ "Marineland Canada website" Archived July 28, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Marineland Canada. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ Lake, Holly (May 4, 2017). "Bill to ban whale and dolphin captivity is being stalled in the Senate — again". Toronto Star.

- ^ "Canada Bans Keeping Whales And Dolphins In Captivity". NPR. Archived from the original on May 5, 2023.

- ^ Thompson, Hannah. "Marineland in south of France again criticised over new whale death". The Connexion.

- ^ Fischer, Sofia (March 30, 2024). "New orca death in French marine park raises questions over animal welfare". Le Monde. Retrieved April 2, 2024.

- ^ Gérard, Mathilde (January 11, 2024). "Animal rights associations fear French water park will send its three orcas abroad". Le Monde. Retrieved April 2, 2024.

- ^ "Loro Parque Website" Loro Parque. Retrieved February 16, 2009. Archived February 26, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ M. Á. Montero / Puerto De La Cruz (October 18, 2010). "Los adiestradores del Loro Parque no tienen titulación oficial". ABC.es. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "Loro Parque da la bienvenida a la cría de la orca Morgan". Archived from the original on June 26, 2022. Retrieved December 8, 2023.

- ^ Humane Society. "Held Captive: Orcas". Archived from the original on September 30, 2011. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ^ 「ありがとう、さよなら」シャチのクーにお別れ 名古屋 2008年9月20日11時32分 asahi.com(朝日新聞社)2013年3月2日閲覧

- ^ シャチの「ナミ」死ぬ 2011年1月14日22時48分 asahi.com(朝日新聞社)2013年3月2日閲覧

- ^ "こんにちはアース part.1". Archived from the original on June 9, 2023. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ "さかまた No.96" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 22, 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2021.

- ^ "鴨川シーワールドと名古屋港水族館の間でシャチ2頭の交換輸送を実施しました". Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ Hall, Jani (March 17, 2017). "China's First Orca Breeding Center Sparks Controversy". National Geographic. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021.

- ^ Li, You (August 20, 2019). "The Activists Fighting to Free China's Captive Killer Whales". Sixth Tone.

- ^ Title 9 CFR Part 3, Subpart E Retrieved March 10, 2014

- ^ Killer whale World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ^ Our Members Archived September 14, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Alliance of Marine Mammal Parks and Aquariums. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ^ Garcia-Roberts, Gus (August 21, 2008). "Seaquarium Activists Push to Free Lolita the Whale". Miami New Times. Retrieved September 6, 2021.

- ^ Moon, Jenna. "The Last Orca". Toronto Star. Retrieved April 18, 2024.

- ^ Orca diet and location Archived March 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Oracle ThinkQuest. Retrieved March 8, 2009

- ^ Hughes, Catherine D. "National Geographic creature feature". Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ^ Ask Shamu Archived October 3, 2013, at the Wayback Machine SeaWorld. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ^ Dierauf, Leslie A Gulland D Frances M, ed. (2001). CRC handbook of marine mammal medicine. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0839-9.

- ^ Comparison Of Amikacin Pharmacokintetics In A Killer Whale (Orcinus orca) And A Beluga Whale (Delphinapterus leucas) American Association of Zoo Veterinarians. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ^ "The Debate – Dangers To Trainers | A Whale Of A Business". Frontline. PBS. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ Resnick, Jane (1994). All about training Shamu. Bridgeport, Conn.: Third Story Books. ISBN 1-884506-11-9.

- ^ Marino, Lori; Rose, Naomi; Visser, Ingrid; Rally, Heather; Ferdowsian, Hope; Slootsky, Veronica (2020). "The harmful effects of captivity and chronic stress on the well-being of orcas". Journal of Veterinary Behavior. 35: 69–82. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2019.05.005.

- ^ Parsons, ECM (2013). An Introduction to Marine Mammal Biology and Conservation. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-7637-8344-0.

- ^ a b Robeck, Todd R.; Willis, Kevin; Scarpuzzi, Michael R.; O'Brien, Justine K. (July 10, 2015). "Comparisons of life-history parameters between free-ranging and captive killer whale (Orcinus orca) populations for application toward species management". Journal of Mammalogy. 96 (5): 1055–1070. doi:10.1093/jmammal/gyv113. ISSN 0022-2372. PMC 4668992. PMID 26937049.

- ^ a b "The Real Story Behind SeaWorld's 'Clearly Wrong' Statement On Its Dying Orca". The Huffington Post. March 11, 2016. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ^ Green, Amy. "Study Concludes Life Expectancy of SeaWorld Orcas Same As In The Wild". WMFE. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

- ^ "World's oldest orca spotted near Vancouver Island". Archived from the original on May 17, 2014.

- ^ "Killer Whale (Orcinus orca)". Retrieved September 12, 2013.

- ^ "Sea World Killer Whale Dies". WOAI-TV. Archived from the original on October 30, 2007. Retrieved October 18, 2007.

- ^ "Killer whale at SeaWorld San Antonio dies". Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on October 23, 2007. Retrieved October 19, 2007.

- ^ "A Second Captive Orca, Taku, Dies from Virus Transmitted By Mosquito Vector". Scribd.com. October 15, 2011. doi:10.1578/AM.35.2.2009.163. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "Keto and Tilikum Express the Stress of Orca Captivity". 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ "Killer Controversy: Why Orcas Should No Longer Be Kept in Captivity" (PDF). 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2015.

- ^ "The First Captive Killer Whales – A Changing Attitude". Rockisland.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c National Marine Fisheries Service Northwest Regional Office (August 2005). "Proposed Conservation Plan for Southern Resident Killer Whales (Orcinus orca)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 21, 2007. Retrieved May 7, 2007.

- ^ "Ask Shamu: Frequently Asked Questions". SeaWorld/Busch Gardens. Archived from the original on October 3, 2013. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- ^ Williams, Vanessa (April 30, 2001). "Captive Orcas 'Dying to Entertain You'" (PDF). Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Ingrid N. Visser. "Prolific body scars and collapsing dorsal fins on killer whales (Orcinus orca) in New Zealand waters" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2008. Retrieved March 28, 2008.

- ^ Hoyt, Erich; Garrett, Howard E.; Rose, Naomi A. "Observations of Disparity Between Educational Material Related to Killer Whales (Orcinus orca) Disseminated by Public Display Institutions and the Scientific Literature" (PDF). Orca Network. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 9, 2022. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ "ABC News: Killer Whale Attacks SeaWorld Trainer". ABC News.

- ^ Kluger, Jeffrey (February 26, 2010). "Killer-Whale Tragedy: What Made Tilikum Snap?". Time. Archived from the original on February 28, 2010. Retrieved March 5, 2010.

- ^ "Inside the mind of a 'killer whale'". Cosmic Log (website). MSNBC. February 25, 2010. Archived from the original on March 1, 2010. Retrieved March 9, 2010.

- ^ "Keep Whales Wild: Trainer Incidents". Retrieved November 5, 2010.

- ^ "Tilikum" Orca Spirit. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ "Park Is Sued Over Death of Man in Whale Tank". The New York Times. Associated Press. September 21, 1999. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ^ "Daniel Dukes Medical Examiners Report". Retrieved August 8, 2013.

Postmortem abrasions, laceration and avulsion of the scrotum with testes. Avulsion of the skin of the pubic area including the scrotal sac and testis, with the left testis separate.

- ^ "OSHA Investigates Trainer's Death, Separate Incident – Orlando News Story – WKMG Orlando". Archived from the original on October 23, 2011.

- ^ "SeaWorld trainer killed by killer whale - CNN.com". CNN. February 25, 2010. Archived from the original on April 3, 2010. Retrieved April 28, 2010. See also: Tilikum

- ^ "What's best for "Tilikum" now, and what have we learned?". Orcanetwork.org. February 24, 2010. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "Secretary of Labor, Complainant v. SeaWorld of Florida – Decision and Order" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on June 8, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- ^ Repard, Pauline (November 30, 2006). "Killer whale bites trainer, takes him to tank bottom". SignOnSanDiego.com. Archived from the original on May 1, 2009.

- ^ "Near Death At SeaWorld: Worldwide Exclusive Video" Huffington Post July 24, 2012.

- ^ "Killer whale attacks Sea World trainer" CNN November 30, 2006.

- ^ "Kasatka" Archived May 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Beyond the Blue. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ M. Á. Montero / Santa Cruz De Tenerife (October 3, 2010). "La orca "Keto" sí atacó y causó la muerte de Alexis, el adiestrador del Loro Parque". ABC.es. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ Moisés Á. Montero / Puerto De La Cruz (November 2010). "Uno de los responsables de las orcas reconoce la "agresión" de "Tekoa" en 2007". ABC.es. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "In the jaws of an orca - ORCAZINE". ORCAZINE. February 29, 2016. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- ^ "Corky's Story" Archived September 10, 2012, at archive.today The Orca Zone. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ "Kanduke" Orca Spirit. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ "Corky's saddest day" Orca Lab. Retrieved September 3, 2014.

- ^ UK. "Behind the bars – Orca in captivity". Bornfree.org.uk. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved April 29, 2014.

- ^ "Captive Orcas 'Dying to Entertain You'" Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ "Gudrun" GeoCities. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ^ Website Dolfinarium, Downloaded on November 5, 2008, from http://www.dolfinarium.nl/index.php?do=content&id=210 Archived February 19, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ SeaWorld Welcomes Newest "Pea" to Pod, press release, SeaWorld Orlando, March 12, 2007. Retrieved June 6, 2007. Archived May 17, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Beyond the Blue: Taima" Free Webs. Retrieved February 12, 2009. Archived March 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sumar" Beyond the Blue. Retrieved February 12, 2009. Archived October 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Killer whale at SeaWorld San Antonio dies". Dallas Morning News. Archived from the original on March 8, 2009. Retrieved June 15, 2008.

External links

[edit]- Further reading Selected bibliography on Orcas from NOAA.