Pembrokeshire

Pembrokeshire

Sir Benfro (Welsh) | |

|---|---|

Tenby in southeast Pembrokeshire | |

Pembrokeshire shown within Wales | |

| Coordinates: 51°50′42″N 4°50′32″W / 51.84500°N 4.84222°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Wales |

| Preserved county | Dyfed |

| Incorporated | 1 April 1996 |

| Administrative HQ | Haverfordwest |

| Government | |

| • Type | Principal council |

| • Body | Pembrokeshire County Council |

| • Control | No overall control |

| • MPs | 2 MPs

|

| • MSs | 2 MSs

|

| Area | |

• Total | 625 sq mi (1,618 km2) |

| • Rank | 5th |

| Population (2022)[2] | |

• Total | 124,367 |

| • Rank | 13th |

| • Density | 200/sq mi (77/km2) |

| Welsh language (2021) | |

| • Speakers | 17.2% |

| • Rank | 8th |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (GMT) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (BST) |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-PEM |

| GSS code | W06000009 |

| Website | pembrokeshire |

Pembrokeshire (/ˈpɛmbrʊkʃɪər, -ʃər/ PEM-bruuk-sheer, -shər; Welsh: Sir Benfro [siːr ˈbɛnvrɔ]) is a county in the south-west of Wales. It is bordered by Carmarthenshire to the east, Ceredigion to the northeast, and otherwise by the sea.[note 1] Haverfordwest is the largest town and administrative headquarters of Pembrokeshire County Council.

The county is generally sparsely populated and rural, with an area of 610 square miles (1,600 km2) and a population of 123,400. After Haverfordwest, the largest settlements are Milford Haven (13,907), Pembroke Dock (9,753), and Pembroke (7,552). St Davids (1,841) is a city, the smallest by population in the UK. Welsh is spoken by 17.2 percent of the population, and for historic reasons is more widely spoken in the north of the county than in the south.

Pembrokeshire's coast is its most dramatic geographic feature, created by the complex geology of the area. It is a varied landscape which includes high sea cliffs, wide sandy beaches, the large natural harbour of Milford Haven, and several offshore islands which are home to seabird colonies. Most of it is protected by Pembrokeshire Coast National Park, and can be hiked on the 190-mile (310 km) Pembrokeshire Coast Path. The interior of Pembrokeshire is relatively flat and gently undulating, with the exception of the Preseli Mountains in the north.

There are many prehistoric sites in Pembrokeshire, particularly in the Preseli Mountains. During the Middle Ages several castles were built by the Normans, such as Pembroke and Cilgerran, and St David's Cathedral became an important pilgrimage site. During the Industrial Revolution the county remained relatively rural, with the exception of Milford Haven, which was developed as a port and Royal Navy dockyard. It is now the UK's third-largest port, primarily because of its two liquefied natural gas terminals. The economy of the county is now focused on agriculture, oil and gas, and tourism.

Settlements

[edit]- See List of places in Pembrokeshire for a comprehensive list of settlements in Pembrokeshire.

The county town is Haverfordwest. Other towns include Pembroke, Pembroke Dock, Milford Haven, Fishguard, Tenby, Narberth, Neyland and Newport. In the west of the county, St Davids is the United Kingdom's smallest city in terms of both size and population (1,841 in 2011). Saundersfoot is the most populous village (more than 2,500 inhabitants)[4] in Pembrokeshire. Less than 4 per cent of the county, according to CORINE, is built-on or green urban.[5]

Geography

[edit]Climate

[edit]| Milford Haven | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There are three weather stations in Pembrokeshire: at Tenby, Milford Haven and Penycwm, all on the coast. Milford Haven enjoys a mild climate and Tenby shows a similar range of temperatures throughout the year,[6] while at Penycwm, on the west coast and 100m above sea level, temperatures are slightly lower.[7]

The county has on average the highest coastal winter temperatures in Wales due to its proximity to the relatively warm Atlantic Ocean. Inland, average temperatures tend to fall 0.5 °C for each 100 metres increase in height.[8]

The air pollution rating of Pembrokeshire is "Good", the lowest rating.[9]

Geology

[edit]The rocks in the county were formed between 600 and 290 million years ago. More recent rock formations were eroded when sea levels rose 80 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous Period. Around 60 million years ago, the Pembrokeshire landmass emerged through a combination of uplift and falling sea levels; the youngest rocks, from the Carboniferous Period, contain the Pembrokeshire Coalfield.[10] The landscape was subject to considerable change as a result of ice ages; about 20,000 years ago the area was scraped clean of soil and vegetation by the ice sheet; subsequently, meltwater deepened the existing river valleys.[11][12] While Pembrokeshire is not usually a seismically active area, in August 1892 there was a series of pronounced activities (maximum intensity: 7) over a six-day period.[13]: 184

Coastline and landscape

[edit]

The Pembrokeshire coastline includes numerous bays and sandy beaches. The Pembrokeshire Coast National Park, the only park in the UK established primarily because of its coastline,[14][15] occupies more than a third of the county. The park contains the Pembrokeshire Coast Path, a near-continuous 186-mile (299 km) long-distance trail from Amroth, by the Carmarthenshire border in the southeast, to St Dogmaels just down the River Teifi estuary from Cardigan, Ceredigion, in the north.[16] The National Trust owns 60 miles (97 km) of Pembrokeshire's coast.[17] Nowhere in the county is more than 10 miles (16 km) from tidal water. The large estuary and natural harbour of Milford Haven cuts deep into the coast; this inlet is formed by the confluence of the Western Cleddau (which flows through Haverfordwest), the Eastern Cleddau, and rivers Cresswell[18] and Carew. Since 1975, the estuary has been bridged by the Cleddau Bridge,[19] a toll bridge carrying the A477 between Neyland and Pembroke Dock. Large bays are Newport Bay, Fishguard Bay, St Bride's Bay and western Carmarthen Bay. There are several small islands off the Pembrokeshire coast, the largest of which are Ramsey, Grassholm, Skokholm, Skomer and Caldey.[20] The seas around Skomer and Skokholm, and some other areas off the Pembrokeshire coast are Marine protected areas.[21]

There are many known shipwrecks off the Pembrokeshire coast with many more undiscovered.[22][23] A Viking wreck off The Smalls has protected status.[24] The county has six lifeboat stations, the earliest of which was established in 1822; in 2015 a quarter of all Royal National Lifeboat Institution Welsh rescues took place off the Pembrokeshire coast.[25]

Pembrokeshire's diverse range of geological features was a key factor in the establishment of the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park and a number of sites of special scientific interest (SSSIs).[26] In the north of the county are the Preseli Mountains, a wide stretch of high moorland supporting sheep farming and some forestry, with many prehistoric sites and the probable source of the bluestones used in the construction of the inner circle of Stonehenge in England.[27] The highest point is Foel Cwmcerwyn at 1,759 feet (536 m), which is also the highest point in Pembrokeshire. Elsewhere in the county most of the land (86 per cent according to CORINE) is used for farming, compared with 60 per cent for Wales as a whole.[5]

Biodiversity

[edit]Pembrokeshire's wildlife is diverse, with marine, estuary, woodland, moorland and farmland habitats.[28][29] The county has a number of seasonal seabird breeding sites, including for razorbill, guillemot, puffin and Manx shearwater,[30] and rare endemic species such as the red-billed chough;[31]: 133–135 Grassholm has a large gannet colony.[32] Seals,[33] several species of whales (including rare humpback whale sightings[34][35]), dolphins and porpoises can be seen off the Pembrokeshire coast; whale-watching boat trips are frequent, particularly during the summer months.[36] An appeal for otter sightings in 2014 yielded more than 100 responses,[37] and a rare visit by a walrus occurred in the spring of 2021.[38]

Pembrokeshire is one of the few places in the UK that is home to the rare Southern damselfly, Coenagrion mercuriale, which is found at several locations in the county, and whose numbers have been boosted by conservation work over a number of years.[39]

Ancient woodland still exists, such as Tŷ Canol Wood, where biofluorescence, seen under ultraviolet light under the dark sky, is a feature that has led to the wood being described as "...one of the most magical and special woodlands in the UK."[40]

The Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales is in the process of restoring a lost temperate rainforest, also known as a Celtic forest, in Trellwyn Fach, near the town of Fishguard.[41] Although temperate rainforests once covered much of western Britain's coasts, they were destroyed over centuries and only remain in fragments.[42] The 59-hectare (150-acre) site will connect with remnants of the remaining rainforest in the Gwaun valley.[43] The project is part of a larger, 100-year Atlantic rainforest recovery programme.[44]

History

[edit]

Human habitation of the region that is now Pembrokeshire extends back to between 125,000 and 70,000 years[45]: 3 and there are numerous prehistoric sites such as Pentre Ifan, and neolithic remains (12,000 to 6,500 years ago), more of which were revealed in an aerial survey during the 2018 heatwave;[46] in the same year, a 1st-century Celtic chariot burial was discovered in Llanstadwell, the first such find in Wales.[47][48] There may have been dairy farming in Neolithic times.[49]

Roman period

[edit]

There is little evidence of Roman occupation in what is now Pembrokeshire. Ptolemy's Geography, written c. 150, mentioned some coastal places, two of which have been identified as the River Teifi and what is now St Davids Head, but most Roman writers did not mention the area; there may have been a Roman settlement near St Davids and a road from Bath, but this comes from a 14th-century writer. Any evidence for villas or Roman building materials reported by mediaeval or later writers has not been verified, though some remains near Dale were tentatively identified as Roman in character by topographer Richard Fenton in his Historical Tour of 1810. Fenton stated that he had "...reason to be of opinion that they had not colonized Pembrokeshire till near the decline of their empire in Britain".[50]: 144

Part of a possible Roman road is noted by CADW near Llanddewi Velfrey,[51] and another near Wiston.[52] Wiston is also the location of the first Roman fort discovered in Pembrokeshire, investigated in 2013.[53] A find in north Pembrokeshire in 2024 of the likely remains of a Roman fort adds to the extent of Roman military presence in the area.[54]

Some artefacts, including coins and weapons, have been found, but it is not clear whether these belonged to Romans or to a Romanised population. Welsh tradition has it that Magnus Maximus founded Haverfordwest, and took a large force of local men on campaign in Gaul in 383 which, together with the reduction of Roman forces in south Wales, left a defensive vacuum which was filled by incomers from Ireland.[55]: 37–51 [better source needed]

Sub-Roman period

[edit]

Between 350 and 400, an Irish tribe known as the Déisi settled in the region known to the Romans as Demetae.[45]: 52, 17, 30, 34 The Déisi merged with the local Welsh, with the regional name underlying Demetae evolving into Dyfed, which existed as an independent petty kingdom from the 5th century.[45]: 52, 72, 85, 87 In 904, Hywel Dda married Elen (died 943),[56] daughter of the king of Dyfed Llywarch ap Hyfaidd, and merged Dyfed with his own maternal inheritance of Seisyllwg, forming the new realm of Deheubarth ("southern district"). Between the Roman and Norman periods, the region was subjected to raids from Vikings, who established settlements and trading posts at Haverfordwest, Fishguard, Caldey Island and elsewhere.[45]: 81–85 [50]: 135–136

Norman period and Middle Ages

[edit]Dyfed remained an integral province of Deheubarth, but this was contested by invading Normans and Flemings who arrived between 1067 and 1111.[45]: 98 The region became known as Pembroke (sometimes archaic "Penbroke"[57]: 53–230 ), after the Norman castle built in the cantref of Penfro. In 1136, Prince Owain Gwynedd at Crug Mawr near Cardigan met and destroyed a 3,000-strong Norman/Flemish army and incorporated Deheubarth into Gwynedd.[58]: 80–85 [45]: 124 Norman/Flemish influence never fully recovered in West Wales.[59]: 79 In 1138, the county of Pembrokeshire was named as a county palatine. Rhys ap Gruffydd, the son of Owain Gwynedd's daughter Gwenllian, re-established Welsh control over much of the region and threatened to retake all of Pembrokeshire, but died in 1197. After Deheubarth was split by a dynastic feud, Llywelyn the Great almost succeeded in retaking the region of Pembroke between 1216 and his death in 1240.[45]: 106, 112, 114 In 1284 the Statute of Rhuddlan was enacted to introduce the English common law system to Wales,[60] heralding 100 years of peace, but had little effect on those areas already established under the Marcher Lords, such as Cemais in the north of the county.[61]: 123–124

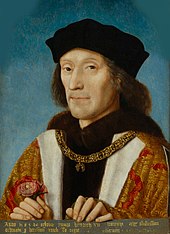

Henry Tudor, born at Pembroke Castle in 1457, landed an army in Pembrokeshire in 1485 and marched to Cardigan via Haverforwest.[55]: 223 [62] Rallying support, he continued to Leicestershire and defeated the larger army of Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field. As Henry VII, he became the first monarch of the House of Tudor, which ruled England until 1603.[63]: 337–379

Tudor and Stuart periods

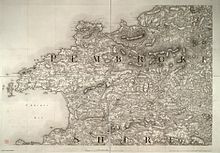

[edit]The Laws in Wales Act 1535 effectively abolished the powers of the Marcher Lords and divided the county into seven hundreds, roughly corresponding to the seven pre-Norman cantrefi of Dyfed.[55]: 247 [64] The hundreds were (clockwise from the northeast): Cilgerran, Cemais, Dewisland, Roose, Castlemartin, Narberth and Dungleddy and each was divided into civil parishes;[65] a 1578 map by Christopher Saxton is the earliest known to show parishes and chapelries in Pembrokeshire;[66] (see list of hundreds and parishes). The Elizabethan era brought renewed prosperity to the county through an opening up of rural industries, including agriculture, mining and fishing, with exports to England and Ireland, though the formerly staple woollen industry had all but disappeared.[55]: 310

During the First English Civil War (1642–1646) the county gave strong support to the Roundheads (Parliamentarians), in contrast to the rest of Wales, which was staunchly Royalist. In spite of this, an incident in Pembrokeshire triggered the opening shots of the Second English Civil War when local units of the New Model Army mutinied. Oliver Cromwell defeated the uprising at the Siege of Pembroke in July 1648.[67]: 437–438 On 13 August 1649, the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland began when New Model Army forces sailed from Milford Haven.[68]

18th and 19th centuries

[edit]

In 1720, Emmanuel Bowen described Pembrokeshire as having five market towns, 45 parishes, and about 4,329 houses, with an area of 420,000 acres (1,700 km2).[69] In 1791 a petition was presented to the House of Commons concerning the poor state of many of the county's roads, pointing out that repairs could not be made compulsory by the law as it stood. The petition was referred to committee.[70]: 178 People applying for poor relief were often put to work mending roads. Workhouses were poorly documented. Under the Poor Laws, costs and provisions were kept to a minimum, but the emphasis was often on helping people to be self-employed. While the Poor Laws provided a significant means of support, there were many charitable and benefit societies.[71] After the Battle of Fishguard, the failed French invasion of 1797, 500 French prisoners were held at Golden Hill Farm, Pembroke.[72] From 1820 to 1878 one of the county's prisons, with a capacity of 86, was in the grounds of Haverfordwest Castle.[73] In 1831, the area of the county was calculated to be 345,600 acres (1,399 km2) with a population of 81,424.[69]

It was not until nearly the end of the 19th century that mains water was provided to rural south Pembrokeshire by means of a reservoir at Rosebush and cast iron water pipes throughout the district.[74]

20th century

[edit]

Throughout much of the 20th century (1911 to 1961) the population density in the county remained stable while it rose in England and Wales as a whole.[75] There was considerable military activity in Pembrokeshire and offshore in the 20th century: a naval base at Milford Haven because German U-boats were active off the coast in World War I[76] The County of Pembroke War Memorial in Haverfordwest carries the names of 1,200 of those that perished in World War I.[77]

The Pembrokeshire War Savings Movement was a local initiative during World War I to encourage county residents to invest in the war effort through the purchase of war bonds and savings certificates. Linking savings with schools was key; schools were the backbone of the 138 war savings associations which were operational in Pembrokeshire in the summer of 1918. The movement continued beyond the end of the war; for the week ending 1 February 1919, some 2,308,810 certificates were sold.[78]

In World War II, military exercises in the Preseli Mountains and a number of military airfields.[79] The wartime increase in air activity saw a number of aircraft accidents and fatalities, often due to unfamiliarity with the terrain.[80] From 1943 to 1944, 5,000 soldiers from the United States Army's 110th Infantry Regiment were based in the county, preparing for D-Day.[81][82] Military and industrial targets in the county were subjected to bombing during World War II.[83] After the end of the war, German prisoners of war were accommodated in Pembrokeshire, the largest prison being at Haverfordwest, housing 600.[84]

In 1972, a second reservoir for south Pembrokeshire, at Llys y Fran, was completed.[85]

Demography

[edit]

Population

[edit]Pembrokeshire's population was 122,439 at the 2011 census,[86] increasing marginally to 123,400 at the 2021 census. 66.4 per cent of residents were born in Wales, while 27.5 per cent were born in England.[87]

Language

[edit]The 2021 census recorded that Welsh is spoken by 17.2 per cent of the population, a fall from 19.2 per cent in 2011.[87] As a result of differential immigration over hundreds of years, such as the influx of Flemish people,[88] the south of the county has fewer Welsh-speaking inhabitants (about 15 per cent) than the north (about 50 per cent). The rough line that can be drawn between the two regions, illustrated by the map, is known as the Landsker Line, and the area south of the line has been termed "Little England Beyond Wales". The first objective, statistically based description of this demarcation was made in the 1960s,[89]: 7–29 but the distinction was remarked upon as early as 1603 by George Owen of Henllys.[90] A 21st century introduction of Welsh place names for villages which had previously been known locally only by their English names has caused some controversy.[91]

Religion

[edit]In 1851, a religious census of Pembrokeshire showed that of 70 per cent of the population, 53 per cent were nonconformists and 17 per cent Church of England (now Church in Wales, in the Diocese of St Davids).[92] The 2001 census for Preseli Pembrokeshire constituency showed that 74 per cent were Christian and 25 per cent of no religion (or not stated), with other religions totalling less than 1 per cent. This approximated to the figures for the whole of Wales.[93] By 2021, 43 per cent reported "no religion", while 48.8 per cent described themselves as Christian. 6.6 per cent did not state their religion, and the remainder represented a number of other religions combined.[87]

Ethnicity

[edit]In 2001, Preseli Pembrokeshire constituency was 99 per cent white European, marginally lower than in 1991, compared with 98 per cent for the whole of Wales. 71 per cent identified their place of birth as Wales and 26 per cent as from elsewhere in the UK.[93] In 2021, 52.7 per cent of residents identified as "Welsh only", a slight decrease since 2011.[87]

Governance, politics and public services

[edit]Under the Local Government Act 1888, an elected county council was set up to take over the functions of the Pembrokeshire Quarter Sessions. It was based at the Shire Hall, Haverfordwest.[94] This and the administrative county of Pembrokeshire were abolished under the Local Government Act 1972, with Pembrokeshire forming two districts of the new county of Dyfed: South Pembrokeshire and Preseli – the split being made at the request of local authorities in the area. Under the same Act, civil parishes[95] were replaced by communities across the whole of Wales.[96][97] In 1996, under the Local Government (Wales) Act 1994, the county of Dyfed was broken up into its constituent parts, and Pembrokeshire has been a unitary authority since then.[98] A new County Hall was built in 1999 in Haverfordwest and serves as the county council's headquarters. In 2017 Pembrokeshire County Council had 60 members and no political party in overall control; there were 34 independent councillors.[99]

In 2009, the question of county names and Royal Mail postal addresses was raised in the Westminster parliament; it was argued that Royal Mail's continued use of the county address Dyfed was causing concern and confusion in the Pembrokeshire business community.[98] The Royal Mail subsequently ceased requiring county names to be used in postal addresses.

In 2018, Pembrokeshire County Council increased council tax by 12.5 per cent, the largest increase since 2004, but the county's council tax remains the lowest in Wales.[100] In 2023 the council published its corporate strategy document for 2023-28.[101]

The Pembrokeshire (Communities) Order 2011 established the most recent arrangement of communities (the successors to civil parishes) in the county which have their own councils; see the foot of this page for a list of communities.[102]

From 2010 to 2024, Pembrokeshire returned two Conservative MPs to the Parliament of the United Kingdom at Westminster: Stephen Crabb for Preseli Pembrokeshire and Simon Hart for South Pembrokeshire which is represented jointly with West Carmarthenshire.[103] The corresponding Members of the Senedd (MSs) returned to the Senedd (Welsh Parliament) in Cardiff are Paul Davies and Samuel Kurtz respectively, both Conservatives.[104]

From 2024, Pembrokeshire was represented by the new UK Parliament constituencies Ceredigion Preseli and Mid and South Pembrokeshire[105] which, in the 2024 General Election, returned Ben Lake (Plaid Cymru)[106] and Henry Tufnell (Labour)[107] respectively.

Pembrokeshire is served by the Mid and West Wales Fire and Rescue Service[108] and Dyfed-Powys Police.[109]

Transport

[edit]

There are no motorways in Pembrokeshire; the nearest is the M4 motorway from London which terminates at the Pont Abraham services in Carmarthenshire some 46 miles (74 km) from Haverfordwest. The A40 crosses Pembrokeshire from the border with Carmarthenshire westwards to Haverfordwest, then northwards to Fishguard.[110] The A477 from St. Clears to Pembroke Dock is 24 miles (39 km) long, of which only 2 miles (3.2 km) are dual carriageway. The Cleddau Bridge, toll-free from 28 March 2019,[111] carries the A477 across the Cleddau Estuary. The A478 traverses eastern Pembrokeshire from Tenby in the south to Cardigan, Ceredigion in the north, a distance of 30 miles (48 km). The A487 is the other major route, running northwest from Haverfordwest to St Davids, then northeast following the coast, through Fishguard and Newport, to the boundary with Ceredigion at Cardigan.[110] Owing to length restrictions in Fishguard, some freight vehicles are not permitted to travel northeast from Fishguard but must take a longer route via Haverfordwest and Narberth.[112] The B4329 former turnpike runs from Eglwyswrw in the north to Haverfordwest across the Preselis.[113]

The main towns in the county are covered by regular bus and train services operated by First Cymru (under their "Western Welsh" livery), Transport for Wales Rail and sometimes Great Western Railway respectively, and many villages by local bus services, or community or education transport.[114]

Pembrokeshire is served by rail via the West Wales Lines from Swansea. Direct trains from Milford Haven run to Manchester Piccadilly. Branch lines terminate at Pembroke Dock, Milford Haven and Fishguard, linking with ferries to Ireland from Pembroke Dock and Fishguard.[115] Seasonal ferry services operate from Tenby to Caldey Island,[116] from St Justinians (St Davids) to Ramsey Island[117] and Grassholm Island,[118] and from Martin's Haven to Skomer Island.[119] Haverfordwest (Withybush) Airport provides general aviation services.[120]

Economy

[edit]Pembrokeshire's economy now relies heavily on tourism; agriculture, once its most important industry with associated activities such as milling, is still significant. Mining of slate and coal had largely ceased by the 20th century. Since the 1950s, petrochemical and liquid natural gas industries have developed along the Milford Haven Waterway and the county has attracted other major ventures. In 2016, Stephen Crabb, then Welsh Secretary, commented in a government press release: "...with a buoyant local economy, Pembrokeshire is punching above its weight across the UK."[121]

In August 2019, the Pembrokeshire County Show celebrated 60 years at Haverfordwest Showground. The organisers anticipated 100,000 visitors, the largest three-day such event in Wales at the time. It showcased agriculture, food and drink, a rugby club, entertainment, with the star attraction a motorcycle display team.[122]

Agriculture

[edit]Until the 12th century, a great extent of Pembrokeshire was virgin woodland. Clearance in the lowland south began under Anglo-Flemish colonisation and under mediaeval tenancies in other areas. Such was the extent of development that by the 16th century there was a shortage of timber in the county. Little is known about mediaeval farming methods, but much arable land was continuously cropped and only occasionally ploughed. By the 18th century, many of the centuries-old open field systems had been enclosed, and much of the land was arable or rough pasture in a ratio of about 1:3.[123]

Kelly's Directory of 1910 gave a snapshot of the agriculture of Pembrokeshire: 57,343 acres (23,206 ha) were cropped (almost half under oats and a quarter barley), there were 37,535 acres (15,190 ha) of grass and clover and 213,387 acres (86,355 ha) of permanent pasture (of which a third was for hay). There were 128,865 acres (52,150 ha) of mountain or heathland used for grazing, with 10,000 acres (4,000 ha) of managed or unmanaged woodland. Estimates of livestock included 17,810 horses, 92,386 cattle, 157,973 sheep and 31,673 pigs. Of 5,981 agricultural holdings, more than half were between 5 and 50 acres.[124]

Pembrokeshire had a flourishing wool industry.[125] There are still working woollen mills at Solva and Tregwynt.[126] One of the last few watermills in Wales producing flour is in St Dogmaels.[127]

Pembrokeshire has good soil and benefits from the Gulf Stream, which provides a mild climate and a longer growing season than other parts of Wales.[128]: 142 Pembrokeshire's mild climate means that crops such as its new potatoes (which have protected geographical status under European law)[129] often arrive in British shops earlier in the year than produce from other parts of the UK. Other principal arable crops are oilseed rape, wheat and barley, while the main non-arable activities are dairy farming for milk and cheese, beef production and sheep farming.[130]

The county lends its name to the Pembroke Welsh Corgi, a herding dog whose lineage can be traced back to the 12th century,[131]: 6 but which in 2015 was designated as a "vulnerable" breed.[132]

Since 2006, Pembrokeshire Local Action Network for Enterprise and Development (PLANED) has provided a forum to promote an integrated approach to rural development, in which communities, public sector and voluntary partners and specialist interest groups come together to influence policy and promote projects aimed at sustainable agriculture. Sub-groups include promoting food and farming in schools and shortening supply chains.[133]

Fishing

[edit]

With Pembrokeshire's extensive coastal areas and tidal river estuaries, fishing was an important industry at least from the 16th century. Many ports and villages were dependent on the fishing.[134] The former large sea fishing industry around Milford Haven is now greatly reduced, although limited commercial fishing still takes place. At its peak, Milford was landing over 40,000 tons of fish a year.[134] Pembrokeshire Fish Week is a biennial event[135] which in 2014 attracted 31,000 visitors and generated £3 million for the local economy.[136]

Mining

[edit]Slate quarrying was a significant industry in the 19th and early 20th centuries with quarrying taking place at about 100 locations throughout the county.[137] Over 50 coal workings in the Pembrokeshire Coalfield were in existence between the 14th and 20th centuries,[138] with the last coal mine, at Kilgetty, closing in 1950.[10][139] Pembrokeshire has 61 disused coal tips; only one of these is in Category C (carrying a potential safety risk), but its location has not been disclosed.[140]

Oil, gas and renewable energy

[edit]

There are two oil refineries, two liquified natural gas (LNG) terminals and the 2,000 MW gas-fired Pembroke Power Station (opened in 2012) at Milford Haven. The LNG terminals on the north side of the river, just outside Milford Haven were opened in 2008;[141] a 196-mile (315 km) pipeline connecting Milford Haven to Tirley in Gloucestershire was completed in 2007.[142] The two oil refineries are operated by Chevron (formerly Texaco) producing 214,000 bbl/d (34,000 m3/d) and Murco (formerly Amoco/Elf) producing 108,000 bbl/d (17,200 m3/d); the latter was sold to Puma Energy in 2015 with the intention of converting it to a storage facility.[143] At the peak, there were a total of five refineries served from around the Haven: the Esso refinery operated from 1960 to 1983, was demolished in the late 1980s and the site converted into the South Hook LNG terminal; the Gulf Refinery operated from 1968 to 1997 and the site now incorporates the Dragon LNG terminal; BP had an oil terminal at Angle Bay which served its refinery at Llandarcy and operated between 1961 and 1985.[144]

The Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority has identified a number of areas in which renewable energy can be, and has been, generated in the county.[145] Following several years of planning after the initial impact studies begun in 2011,[146] the first submarine turbine of three was installed in Ramsey Sound in December 2015.[147] The cumulative impact of single and multiple wind turbines is not without controversy[148] and was the subject of a comprehensive assessment in 2013.[149] In 2011 the first solar energy farm in Wales was installed at Rhosygilwen, Rhoshill with 10,000 panels in a field of 6 acres (2.4 ha), generating 1 MW.[150]

Tourism

[edit]

Pembrokeshire's tourism portal is Visit Pembrokeshire, run by Pembrokeshire County Council.[151] In 2015 4.3 million tourists visited the county, staying for an average of 5.24 days, spending £585 million; the tourism industry supported 11,834 jobs.[152] Many of Pembrokeshire's beaches have won awards,[153] including Poppit Sands and Newport Sands.[154] In 2018, Pembrokeshire received the most coast awards in Wales, with 56 Blue Flag, Green Coast or Seaside Awards.[155][156] In the 2019 Wales Coast Awards, 39 Pembrokeshire beaches were recognised, including 11 awarded Blue Flag status.[157]

The Pembrokeshire coastline is a major draw to tourists; in 2011 National Geographic Traveller magazine voted the Pembrokeshire Coast the second best in the world and in 2015 the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park was listed among the top five parks in the world by a travel writer for the Huffington Post.[158] Countryfile Magazine readers voted the Pembrokeshire Coast the top UK holiday destination in 2018,[159] and in 2019 Consumers' Association members placed Tenby and St Davids in the top three best value beach destinations in Britain.[160] With few large urban areas, Pembrokeshire is a "dark sky" destination.[161] The many wrecks off the Pembrokeshire coast attract divers.[23] The decade from 2012 saw significant, increasing numbers of Atlantic bluefin tuna, not seen since the 1960s, and now seen by some as an opportunity to encourage tourist sport fishing.[162]

The county has a number of theme and animal parks (examples are Folly Farm Adventure Park and Zoo, Manor House Wildlife Park, Blue Lagoon Water Park and Oakwood Theme Park), museums and other visitor attractions including Castell Henllys reconstructed Iron Age fort, Tenby Lifeboat Station and Milford Haven's Torch Theatre.[151] There are 21 marked cycle trails around the county.[163]

Pembrokeshire Destination Management Plan for 2020 to 2025 sets out the scope and priorities to grow tourism in Pembrokeshire by increasing its value by 10 per cent in the five years, and to make Pembrokeshire a top five UK destination.[164]

Culture

[edit]Flag

[edit]The flag of Pembrokeshire is a yellow cross on a blue field; in the centre of the cross is a green pentagon bearing a red and white Tudor rose, divided quarterly and counterchanged, the inner and outer roses having alternating red and white quarters.[165][166]

Physical heritage

[edit]

Pembrokeshire has more than 1,600 listed buildings, ranging from mud huts to castles, and including bridges and other ancient and modern structures, under the auspices of Cadw and the County Council.[167] The National Monuments Record of Wales of the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales identifies nearly 6,000 sites in Pembrokeshire as worthy of study, preservation and recording, including prehistoric and modern buildings, wrecks and natural features.[168] There are 10 National Trust properties in Pembrokeshire.[169]

The arts and media

[edit]Music festivals in Pembrokeshire include those at St Davids, Fishguard (folk, jazz and the International Music Festival) and Tenby (Blues Festival).[170] Milford Haven's Torch Theatre produces drama, screens films and holds exhibitions of art and crafts,[171] and there is a theatre-cinema in Fishguard (Theatr Gwaun)[172] and a cinema in Haverfordwest.[173] There are museums and art galleries in several locations in the county, including Scolton Manor, Narberth, Tenby, Milford Haven and Fishguard;[174] in Fishguard, the 100 feet (30 m) long Last Invasion Tapestry, commemorating the Battle of Fishguard in 1797, is on display.[175] The Llangwm Literary Festival is a literary festival held in Llangwm.[176]

Pembrokeshire's coastal landscape and wealth of historic buildings has made it a popular location choice for film and television, including Moby Dick at Fishguard, and the final two Harry Potter films at Freshwater West. Others include:

There are seven local newspapers based in Pembrokeshire: the Western Telegraph (the largest in Pembrokeshire), The Milford Mercury, Tenby Observer, Pembroke Observer, County Echo and The Pembrokeshire Herald (founded 2013.[197] The Milford Mercury (circulation 3,681) and Western Telegraph (circulation 19,582) are part of the Newsquest group. Radio Pembrokeshire, and several other West Wales radio stations, were broadcast from Narberth until 2016, when they were relocated to the Vale of Glamorgan, while retaining satellite offices at Narberth and Milford Marina.[198][199]

Sport

[edit]As the national sport of Wales, rugby union is widely played throughout the county at both town and village level. Haverfordwest RFC, founded in 1875, is a feeder club for Llanelli Scarlets. Village team Crymych RFC in 2014 plays in WRU Division One West.[200] There are numerous football clubs in the county, playing in five leagues with Haverfordwest County A.F.C. competing in the Cymru Premier.[201]

Triathlon event Ironman Wales has been held in Pembrokeshire since 2011, contributing £3.7 million to the local economy, and the county committed in 2017 to host the event for a further five years.[202] Ras Beca, a mixed road, fell and cross country race attracting UK-wide competitors, has been held in the Preselis annually since 1977. The record of 32 minutes 5 seconds has stood since 1995.[203] Pembrokeshire Harriers athletics club was formed in 2001 by the amalgamation of Cleddau Athletic Club (established 1970) and Preseli Harriers (1989) and is based in Haverfordwest.[204]

The annual Tour of Pembrokeshire road-cycling event takes place over routes of optional length.[205] The 4th Tour, in April 2015, attracted 1,600 riders including Olympic gold medallist Chris Boardman[206] and there were 1,500 entrants to the 2016 event.[207] Part of Route 47 of the Celtic Trail cycle route is in Pembrokeshire. The Llys y Fran Hillclimb is an annual event run by Swansea Motor Club,[208] and there are several other county motoring events held each year.[209]

Abereiddy's Blue Lagoon was the venue for a round of the Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series in 2012,[210] 2013,[211] and 2016;[212] the Welsh Surfing Federation has held the Welsh National Surfing Championships at Freshwater West for several years,[213] and Llys y Fran Country Park hosted the Welsh Dragonboat Championships from 2014 to 2017.[214][215]

While not at major league level, cricket is played throughout the county and many villages such as Lamphey, Creselly, Llangwm, Llechryd and Crymych field teams in minor leagues under the umbrella of the Cricket Board of Wales.[216]

Notable people

[edit]

From mediaeval times, Rhys ap Gruffydd (c. 1132-1197), ruler of the kingdom of Deheubarth, was buried in St Davids Cathedral.[217] and Gerald of Wales was born c. 1146 at Manorbier Castle.[218] Henry Tudor (later Henry VII) was born in 1457 at Pembroke Castle.[219]

Robert Recorde, inventor of the equals sign (=) in mathematics was from Tenby.[220]

The pirate Bartholomew Roberts (Black Bart) (Welsh: Barti Ddu) was born in Casnewydd Bach, between Fishguard and Haverfordwest in 1682.[221]

In later military history, Jemima Nicholas, heroine of the so-called "last invasion of Britain" in 1797, was from Fishguard,[222] Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Picton GCB, born in Haverfordwest, was killed at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815[223] and Private Thomas Collins is believed to be the only Pembrokeshire man that fought in the Battle of Rorke's Drift in 1879.[224]

In the arts, siblings Gwen and Augustus John were both born in Pembrokeshire,[225]: 251–252 as was the novelist Sarah Waters;[226] singer Connie Fisher grew up in Pembrokeshire.[227] The actor Christian Bale was born in Haverfordwest.[228]

Stephen Crabb, a former Secretary of State for Work and Pensions and Secretary of State for Wales, was brought up in Pembrokeshire and until 2024 was one of the county's two Members of Parliament,[229] the other being Simon Hart,[103] who served as Secretary of State for Wales from 2019 to 2022.[230][231]

Education and health

[edit]A comprehensive review of education in Pembrokeshire was carried out in 2014 with a number of options for discussion in 2015.[232] In 2018 there were 58 primary schools, eight secondary schools (two for ages 3 to 16) and one special school, in all providing education for more than 18,300 pupils. These include 15 Welsh medium primary schools in the county, three dual stream schools and two transition schools; four primary schools are classified as English Welsh schools (English medium schools with significant use of Welsh). In 2017/18, 22 per cent of seven-year-old pupils were educated through the medium of Welsh. This figure was expected to rise to 25 per cent by 2019/20.[233] In 2019, there were two fewer primary schools. The local authority's education budget for 2019/2020 was £88 million, equating to £4,856 per pupil. A February 2020 report by schools' inspection body Estyn, however, considered the local authority's performance in education provision "a significant concern".[234]

Pembrokeshire has had a branch of the University of the Third Age (U3A) since 1991 and has a wide range of groups.[235][236][237]

Health services in the county are provided by Hywel Dda University Health Board which also provides for Ceredigion and Carmarthenshire. The county's principal hospital is Withybush General Hospital in Haverfordwest,[238] with local hospitals in Tenby[239] and Pembroke Dock.[240] In November 2018, the health board informed Pembrokeshire's Community Health Council that the county had 38 full-time and 34 part-time GPs.[241]

See also

[edit]- List of national parks of England and Wales

- List of castles in Pembrokeshire

- List of Scheduled prehistoric Monuments in north Pembrokeshire

- List of Scheduled prehistoric Monuments in south Pembrokeshire

- List of Scheduled Roman to modern Monuments in Pembrokeshire

- List of Lord Lieutenants of Pembrokeshire

- List of Custodes Rotulorum of Pembrokeshire

- List of High Sheriffs of Pembrokeshire

- List of MPs for the former county of Pembrokeshire

- Cuisine of Pembrokeshire

Notes

[edit]- ^ Clockwise from Carmarthen Bay: Bristol Channel, Celtic Sea/Atlantic Ocean, St George's Channel/Irish Sea. There are no clearly-defined boundaries between these bodies of water.

References

[edit]- ^ "Council & Democracy". Pembrokeshire County Council. 30 November 2016. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ a b "Mid-Year Population Estimates, UK, June 2022". Office for National Statistics. 26 March 2024. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "How life has changed in Pembrokeshire: Census 2021". Office for National Statistics. 19 January 2023. Retrieved 6 August 2024.

- ^ "Saundersfoot: Ward and community population 2011". UK Census Data. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ a b Easton, Mark (9 November 2017). "How much of your area is built on?". BBC News. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- ^ "Tenby climate information". Met Office. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ "Penycwm climate information". Met Office. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ "Wales: Climate". Met Office. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ^ "Pollution hotspots revealed: Check your area". BBC News. 10 January 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Coal Mining". Pembrokeshire Virtual Museum. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- ^ "Geology". Pembrokeshire Virtual Museum. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ Howells, Sid. "Geological History of Pembrokeshire". pembrokeshireonline.co.uk. Retrieved 21 June 2016.

- ^ Davison, Charles (2009) [1924]. A History of British Earthquakes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-14099-7. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "Exploring the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park". Visit Wales. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Coast National Park, Wales". National Geographic. 2 November 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Coast Path". nationaltrail.co.uk. National Trails. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ "£40K cash boost for Pembrokeshire conservation project". BBC News. 27 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ "River Cresswell". Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ^ "Cleddau Bridge". Hansard. 8 December 1994. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire's Islands". Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ "Skomer, Skokholm and the Seas off Pembrokeshire". Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ Prior, Neil (26 October 2014). "Pembrokeshire has 'thousands' of undiscovered wrecks - diver". BBC News. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Wrecks around Pembrokeshire". Dive Pembrokeshire UK. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- ^ Hayward, Will (6 January 2018). "The hidden wrecks of Wales that you never knew were there". Wales online. Retrieved 11 January 2018.

- ^ "Quarter of all 2015 Welsh lifeboat rescues were off Pembrokeshire". Milford & West Wales Mercury. 27 January 2016. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire's geology". Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "Mynydd Preseli". Dyfed Archaeological Trust. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire". The Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ Davies, Andy (10 July 2012). "Top 10 wildlife spots in Pembrokeshire - in pictures". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Seasonal seabirds". Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1994). Crows and jays: a guide to the crows, jays and magpies of the world. London: Christopher Helm / A & C Black. ISBN 978-0-7136-3999-5.

- ^ "Grassholm Island". Visit Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ "Seal watching in Pembrokeshire". Visit Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Humpback whale spotted off Pembrokeshire coast". BBC News. 14 August 2021. Retrieved 14 August 2021.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire: Humpback whale spotted near Welsh port". BBC News. 20 January 2024. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ "Whale and Dolphin watching in Pembrokeshire". Visit Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "100 otters spotted on Pembrokeshire coast after appeal". BBC News. 17 June 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Walrus spotted in Wales". BBC News. 20 March 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ^ "Southern damselfly boosted in Pembrokeshire by 'fantastic' conservation". BBC. 24 September 2020. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- ^ "Biofluorescence: Unseen world of the Celtic rainforest revealed by UV". Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire: Plan to restore Celtic rainforests". BBC News. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire announced as new location for Atlantic rainforest restoration". 15 July 2024. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ "Lost Atlantic rainforest to be restored in South West Wales". Forestry Journal. 15 July 2024. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ Houghton, Amy (16 July 2024). "A lost ancient rainforest in Wales is being brought back to life". Time Out. Retrieved 6 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Davies, John (1994). A History of Wales. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-014581-6.

- ^ "Heatwave crop marks reveal 200 ancient sites in Wales". BBC News. 28 December 2018. Retrieved 29 December 2018.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire chariot burial finds ruled as treasure". BBC News. 31 January 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Huw Thomas (26 June 2019). "Late Iron Age chariot pieces found in Pembrokeshire". BBC News. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- ^ Prior, Neil (12 August 2021). "Trellyffaint: Proof unearthed of Neolithic dairy farming in Pembrokeshire". BBC News. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ a b Fenton, Richard (1811). A historical tour through Pembrokeshire. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme & co.

- ^ Cadw. "Roman Road 300m East of Bryn Farm (PE472)". National Historic Assets of Wales.

- ^ "Roman road W of Carmarthen; Via Julia, possible features NE of Wiston (309510)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ "Dyfed Archaeological Trust: Wiston Roman Fort". Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- ^ Sarah Bowdidge. "New find hints Wales fully-integrated into Roman Britain". Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d Laws, Edward (1888). The History of Little England Beyond Wales. London: George Bell.

- ^ "The Chronicle of the Princes". Archaeologia Cambrensis. 4. 10: 25. 1864. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Pughe, William Owen (1799). Cambrian Register for the Year 1796, Vol. II. London: E & T Williams. Retrieved 7 May 2015.

- ^ Lloyd, J. E. (2004). A History of Wales: From the Norman Invasion to the Edwardian Conquest. New York: Barnes & Noble. ASIN B01FKW4P94.

- ^ Warner, Philip (1997). Famous Welsh Battles. New York: Barnes & Noble. ASIN B01K3MUPM2.

- ^ Francis Jones (1969). The Princes and Principality of Wales. University of Wales Press. ISBN 978-0-900768-20-0. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ Rees, David (1997). The son of prophecy: Henry Tudor's road to Bosworth (2nd., rev. ed.). London: J. Jones. ISBN 978-1-871083-01-9.

- ^ Rees, David (1985). The Son of Prophecy: Henry Tudor's Road to Bosworth. Black Raven Press. ISBN 978-0-85159-005-9.

- ^ Davies, Norman (2000). The Isles – A History. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-69283-7.

- ^ "Laws in Wales Act 1535 (repealed 21.12.1993) (c.26)". statutelaw.gov.uk. The National Archive. 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Hundreds and Parishes". GENUKI: UK & Ireland Genealogy. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ "Penbrok comitat". British Library. Archived from the original on 27 September 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2024.

- ^ Royle, Trevor (2005). Civil War: The War of the Three Kingdoms 1638–1660. London: Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11564-1.

- ^ "Timelines: 1649". BCW Project. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ^ a b "Pembrokeshire". GENUKI: UK & Ireland Genealogy. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ Journals of the House of Commons. Vol. 46. London: HM Stationery Office. 1803. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ^ Hancock, Simon (9 December 2016). "Aspects of the Old Poor Law". Pembrokeshire Historical Society. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ "Golden Hill Prison (412561)". Coflein. RCAHMW. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire council to sell old Haverfordwest prison". BBC News. 9 July 2010. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ "Pembroke Borough Waterworks". The Pembrokeshire Herald. 14 April 1882. Retrieved 20 July 2019.

- ^ "Current rate: Population Density (Persons per Acre)". visionofbritain.org.uk. A Vision of Britain through Time. Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire's front line role in the U-boat war". Western Telegraph. 12 November 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Historical Society: The story behind the Pembrokeshire County Great War Monument at Haverfordwest". 12 December 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ Hancock, Simon (2023). "Duty and Personal Advantage Combined: The War Savings Movement in Pembrokeshire during the First World War". The Welsh History Review. 31 (3) – via Ingenta connect.

- ^ Thomas, Roger, ed. (2013). A Guide to the Military Heritage of Pembrokeshire. Compiled by local historians. Planed. Retrieved 22 June 2014.

- ^ "Military aircraft crash sites in south-west Wales" (PDF). Dyfed Archaeological Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire memorial plan for US D-Day servicemen". BBC News. 19 March 2019. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- ^ "D-Day: Pembrokeshire memorial unveiled for US soldiers". BBC News. 22 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- ^ "Air Raids". Pembrokeshire Virtual Museum. Archived from the original on 12 December 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "German Prisoners of War in Pembrokeshire". Western Telegraph. 19 November 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2018.

- ^ "Llys y Fran Reservoir and Country Park". Archived from the original on 14 January 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2014.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire". UK Census data. Archived from the original on 25 January 2018. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d "How life has changed in Pembrokeshire: Census 2021". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ "The Flemish Colonists in Wales". BBC Legacies. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ John, Brian (1972). "The Linguistic Significance of the Pembrokeshire Landsker". The Pembrokeshire Historian. 4. Haverfordwest: The Pembrokeshire Community Council. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ Owen, George (1994). Miles, Dillwyn (ed.). The Description of Pembrokeshire (First ed.). Llandysul: Gomer Press. ISBN 978-1-85902-120-0.

- ^ Lynch, David (26 June 2018). "Concerns over new standard place name spellings for Pembrokeshire villages". Western Telegraph. Retrieved 30 December 2018.

- ^ Jones, Ray (2017). "The 1851 Religious Census in Pembrokeshire". Pembrokeshire Historical Society. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ a b "2001 Census of Population for Preseli Pembrokeshire" (PDF). Research Paper 03/044. Assembly Wales. April 2003. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- ^ Cadw. "The Shire Hall (12110)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 5 October 2021.

- ^ "Ordnance Survey: Civil parishes". National Library of Scotland. 1909. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ Wood, Bruce (1976). The Process of Local Government Reform: 1966–1974. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-350052-1.

- ^ Local Government Act 1972. 1972 c.70. The Stationery Office Ltd. 1997. ISBN 0-10-547072-4.

- ^ a b "Westminster Hall Debate: Pembrokeshire (Royal Mail Database)". Hansard. 23 June 2009. Column 218WH. Retrieved 5 February 2017.

- ^ "Your Councillors". Pembrokeshire County Council. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "Monthly bin collection: Conwy council warns of tax hike". BBC News. 26 September 2018. Retrieved 26 September 2018.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire County Council: Corporate Strategy 2023-2028". 2 October 2023. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ "The Pembrokeshire (Communities) Order 2011". legislation.gov.uk. The National Archive. 7 March 2011. 2011 No. 683 (W.101). Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ a b "All change in Carmarthen and Pembrokeshire". BBC News. 7 May 2010. Election 2010. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ Jones, Ciaran (6 May 2016). "Assembly Election 2016: The full list of Welsh AMs". WalesOnline. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- ^ "2023 Parliamentary Review - Revised Proposals | Boundary Commission for Wales". Boundary Commission for Wales. 19 October 2022. Retrieved 20 June 2023.

- ^ "Ben Lake MP". U K Parliament. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "General Election 2024 results live as Labour wins seats from the Tories in Wales". Wales Online. 5 July 2024. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ "Mid and West Wales Fire and Rescue Service". Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ "Dyfed-Powys Police". Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ a b "Pembrokeshire" (Map). Pembrokeshire. Microsoft. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Neil Prior (28 March 2019). "Cleddau Bridge toll-free after 44 years". BBC News. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Humfrey, Anwen (27 June 2010). "Lower Town, Fishguard, still blighted by lorry chaos". Western Telegraph. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ Pembrokeshire (Map) (Landranger ed.). Ordnance Survey. 2007. §§ 145, 157, 158.

- ^ "Public transport". Pembrokeshire County Council. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ^ "Route Map". Transport for Wales. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Caldey Island". Tenby Guide. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "Ramsey Island". Visit Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "Grassholm Island". Visit Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "Skomer Island". Visit Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "Haverfordwest - EGFE". NATS Aeronautical Information Service. Archived from the original on 16 February 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- ^ Crabb, Stephen (18 March 2016). "Pembrokeshire is punching above its weight with a strong local economy". gov.uk. Office of the Sectretary of State for Wales. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire County Show gets underway in the sun". Western Telegraph. 13 August 2019. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Farming c1580-1620". GENUKI: UK & Ireland Genealogy. Archived from the original on 13 December 2014. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "Agricultural Statistics 1908". GENUKI: UK & Ireland Genealogy. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "Woollen Mills Working and Weaving in West Wales". The Real Wales. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Mills Open to the Public". Welsh Mills Society. 14 September 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ Parkinson, Dave (11 February 2019). "Chance to look behind the scenes at St Dogmaels water mill". Tivyside Advertiser. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ Davies, Gilli (1995). A Taste of Wales (First ed.). London: Pavilion Books. ISBN 978-1-85793-293-5.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Early Potato gets protected European status". BBC News. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ "Types of Farming". Pembrokeshire Virtual Museum. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Wheeler, Jill C. (2010). Welsh Corgis. Edina, MN: ABDO Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60453-786-4.

- ^ Sawer, Patrick (8 February 2015). "The Queen's Corgis designated a 'vulnerable' breed". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 16 May 2015.

- ^ "Sustainable agriculture and natural resources". PLANED. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ a b "The Fishing Industry". Pembrokeshire Virtual Museum. 24 June 2013. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Fish Week". Wales Online. 3 June 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ^ Misstear, Rachael (28 November 2014). "Why fish are proving to be Pembrokeshire's newest tourism asset". Wales Online. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Tucker, Gordon & Mary (1983). Griffith-Jones, Bill (ed.). The old slate industry of Pembrokeshire and other parts of South Wales. Vol. XXIII/2, Winter. Aberystwyth: National Library of Wales journal.

- ^ Edwards, George (1963). "The Coal Industry in Pembrokeshire". Contributed by Delyth Wilson (April 2007). GENUKI: UK & Ireland Genealogy. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ^ Scourfield, Aled (14 February 2019). "New plaque for Pembrokeshire's 'forgotten' pit disaster". BBC News. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- ^ "Coal tips: Areas of Wales with most higher-risk sites revealed". BBC News. 26 October 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ "Timeline: LNG plants in Wales". BBC News. 19 March 2009. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "Controversial gas pipe completed". BBC News. 27 November 2007. Retrieved 15 February 2009.

- ^ "Puma Energy buys Murco Milford Haven oil refinery site". BBC News. 13 March 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- ^ "Angle Bay BP oil terminal and pumping station, Popton, Milford Haven (306321)". Coflein. RCAHMW. 14 April 2010. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ "Renewable energy sources". Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority. Retrieved 3 March 2019.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire tidal power impact studied". BBC News. 8 May 2011. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ "Giant tidal turbine placed on seabed off Pembrokeshire". BBC News. 13 December 2015. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ "Wind turbine plans in Pembrokeshire continue to generate debate". Western Telegraph. 10 April 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire and Carmarthenshire: Cumulative Impact of Wind Turbines on Landscape and Visual Amenity guidance" (PDF). Pembrokeshire Coast National Park Authority. 11 December 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ ap Dafydd, Iolo (8 July 2011). "Wales' first solar park powers up in Pembrokeshire". BBC News. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ^ a b "Welcome to Pembrokeshire". Visit Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "£585 million Pembrokeshire tourism boost". Western Telegraph. 23 July 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire's award winning beaches". Visit Pembrokeshire. May 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- ^ "Ceredigion and Pembrokeshire beaches get top award". Tivyside Advertiser. 17 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Top awards for beautiful Pembrokeshire beaches". Western Telegraph. 17 May 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- ^ "Wales beaches praised in Keep Wales Tidy Blue Flag awards". BBC News. 17 May 2018. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire beaches claim 11 Blue Flags in 2019 Wales Coast Awards". Western Telegraph. 15 May 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Coast National Park named among the five best in the world". Western Telegraph. 22 May 2015. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ^ "BBC Countryfile Magazine Awards 2018". Visit Pembrokeshire. January 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- ^ "Best value British beach towns". Consumers Association. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Coast National Park: Dark sky destination". Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ Messenger, Steffan (1 April 2021). "Giant bluefin tuna return in Wales a 'massive opportunity'". BBC News. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire County Council: Cycle Pembrokeshire". 23 March 2018. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Destination Management Plan 2020 to 2025" (PDF). Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire flag". flaginstitute.org. Flag Institute. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire flag". CRWFlags.com. CRW Flags Inc. Retrieved 6 July 2016.

- ^ "Listed Buildings". Pembrokeshire County Council. 24 January 2018. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire: Sites". coflein.gov.uk. Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments of Wales. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire". National Trust. Retrieved 27 February 2018.

- ^ "Music in Pembrokeshire". Visit Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ "The Torch Theatre". Visit Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ "Theatr Gwaun". Visit Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ "Secret history of Pembrokeshire's forgotten cinemas rediscovered". Western Telegraph. 14 January 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ "Museums and art galleries". Visit Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- ^ "Last Invasion Tapestry". Visit Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ^ "Llangwmlitfest". www.llangwmlitfest.co.uk. Retrieved 30 July 2023.

- ^ "The Thief of Bagdad". IMDb. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d e "Lights, camera, action: Welsh film & TV locations". Visit Wales. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ^ "Fury at Smuggler's Bay". IMDb. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ "Jaberwocky". IMDb. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ "Dragonworld". IMDb. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ Jasper Rees (28 April 1994). "All aboard the unsinkable soap opera". Independent. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ "Basil". IMDb. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ "Baltic Storm". IMDb. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ "I Capture the Castle". IMDb. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ Youngman, Angela (2011). In the Footsteps of Robin Hood (eBook). Oxted: Collca. ISBN 978-1-908795-00-7.

- ^ "Third Star". IMDb. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- ^ Miller, Charles D. (8 June 2012). "Chapter 10—Site #38: Freshwater West Beach, Pembrokeshire, Wales". Harry Potter Places: Snitch-Seeking in Southern England and Wales, Book 3. London: First Edition Design Pub. ISBN 978-1-937520-98-4.

- ^ McDowell, Martin (21 September 2011). "Filming Snow White and the Huntsman at Marloes Sands". Archived from the original on 28 January 2012. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ Moore, Sarah (23 June 2014). "Solva taken over for Under Milkwood filming". BBC News. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ Jones, Hannah (27 March 2015). "Bad Education takes over Pembroke Castle for film version of the hit show". Wales online. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "Premiere for new film Their Finest shot in Wales". BBC News. 18 April 2017. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- ^ Sinclair, Bruce (10 May 2016). "Me Before You movie release will see Pembroke on the silver screen". Western Telegraph. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ^ "Luke Evans: The Pembrokeshire Murders sees actor return to Wales". BBC. 7 January 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- ^ Cremona, Patrick (13 January 2021). "Where was The Pembrokeshire Murders filmed?". Radio Times. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ^ Clarke, Cath (27 August 2021). "The Toll review – toll booth man with no name fights back in jokey Welsh western". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- ^ Moore, Sarah (5 July 2013). "Third new local newspaper launched in Wales". BBC News. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- ^ "Jobs at risk as Nation Broadcasting plans to relocate stations". BBC News. 14 September 2016. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Mumford, Martin (March 2016). "Radio Pembrokeshire Public file" (PDF). Radio Pembrokeshire. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ "SWALEC League: 1 West". Welsh Rugby Union Wales. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Sport: Football". Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "New five-year Ironman Wales deal confirmed for Tenby". BBC News. 7 September 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2017.

- ^ Lewis, Sue (13 August 2014). "All set for Beca event". Tivyside Advertiser. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Harriers: Club history". pembrokeshireharriers.org.uk. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- ^ "Tour of Pembrokeshire". tourofpembrokeshire.co.uk. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ^ Sinclair, Thomas (22 April 2015). "Gold medallist to ride Tour of Pembrokeshire". Pembrokeshire Herald. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ^ Coles, Jon (20 May 2016). "Cycling tour a resounding success!". Pembrokeshire Herald. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ^ "Llys-Y-Fran Hillclimb Guide". Motorsportcircuits.co.uk. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ Bruce Sinclair (10 June 2019). "Classic motors delight on 2019 Bluestone Run". BBC News. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ Aaron, Martin (8 September 2012). "Red Bull Cliff Diving World Series' Pembrokeshire UK debut". BBC News. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ Neal, Abigail (13 September 2013). "World Series cliff divers brave Pembrokeshire cliffs". BBC News. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ Coleman-Phillips, Ceri (10 September 2016). "Cliff diving: 'It's always a jump into the unknown'". BBC News. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ "Welsh Surf News". The Welsh Surfing Federation. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ^ "Country Park welcomes Welsh Dragonboat Championships". BBC News. 29 May 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- ^ "Hear the dragons roar at rowing championship tomorrow". Milford Mercury. 27 May 2017. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- ^ "Directory Of Clubs". Cricket Wales. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ Jones Pierce, Thomas (1959). "RHYS ap GRUFFYDD (1132 - 1197), lord of Deheubarth, known in history as ' Yr Arglwydd Rhys ' (' The lord Rhys ')". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ MacCaffrey, James (1909). "Giraldus Cambrensis". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved 17 February 2018 – via New Advent.

- ^ Rogers, Caroline; Turvey, Roger (2005). Access to History: Henry VII (3rd ed.). London: Hodder Murray. ISBN 978-0-340-88896-4.

- ^ Johnston, Stephen (2004). "Recorde, Robert (c. 1512–1558)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/23241. Retrieved 1 November 2024. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Yount, Lisa (2002). Pirates. Lucent Books. ISBN 1-56006-955-4.

- ^ "Invasion heroine's records find". BBC News. 4 April 2006. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ Johnston, Samuel Henry Fergus (1959). "PICTON, Sir THOMAS (1758-1815), a soldier". Dictionary of Welsh Biography. National Library of Wales. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "Plan to honour Rorke's Drift hero". BBC News. 22 January 2006. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ Holroyd, Michael (2002). "Augustus John". In Mintle, Justin (ed.). Makers of Modern Culture. Vol. 1. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-26583-6. Retrieved 29 January 2018.

- ^ Allardice, Lisa (1 June 2006). "Uncharted Waters". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ Hotchin, Becky (16 September 2006). "Pembrokeshire's Maria - Vote Connie". pembrokeshiretv.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007.

- ^ Francis, Damien (22 July 2008). "Batman star Christian Bale arrested". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 31 August 2022.

- ^ Shute, Joe (26 March 2016). "From council house to cabinet: the unlikely childhood of Stephen Crabb". Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 31 January 2018.

- ^ "Simon Hart appointed new Welsh secretary". BBC News. 16 December 2019. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- ^ "Simon Hart resigns as Secretary of State for Wales". Sky News. Retrieved 20 July 2023.

- ^ "Closure of Sir Thomas Picton, Tasker Milward, Ysgol Dewi Sant and Ysgol Bro Gwaun Schools planned in huge shake-up". Western Telegraph. 22 January 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire Schools". Pembrokeshire County Council. 28 April 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- ^ Abbie Wightwick (12 February 2020). "Schools in Pembrokeshire are a 'significant concern', says inspections body Estyn". Wales Online. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ Searle, Ian (16 June 2011). "Education: the age of uncertainty". The Independent. Archived from the original on 25 May 2022. Retrieved 25 January 2015.

- ^ "U3A Pembrokeshire". Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ "Pembrokeshire County Council: Lifelong learning". 20 July 2017. Retrieved 14 February 2020.

- ^ "Withybush General Hospital, Haverfordwest". wales.nhs.uk. University Health Board. 2 January 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ "Tenby Cottage Hospital" (PDF). wales.nhs.uk. Pembrokeshire and Derwen NHS Trust. March 2006. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ^ "South Pembrokeshire Hospital". wales.nhs.uk. University Health Board. 3 October 2018. Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- ^ "Pressure on GP surgeries in Pembrokeshire". Tivyside Advertiser. 14 November 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2018.

Further reading

[edit]- Awbery, G. M. (1986). Pembrokeshire Welsh, A Phonological Study (First ed.). Cardiff: National Museum of Wales. ASIN B000S54DVE.

- Charles, B. G. (1992). The Place-Names of Pembrokeshire (2 Volumes) (First ed.). Cardiff: National Museum of Wales. ISBN 978-0-907158-58-5.

- Charles-Jones, Caroline (2001). Historic Pembrokeshire Homes and Their Families: The Francis Jones. Illustrations by Leon Olin & David H. White Jr. (2nd Revised ed.). Dinas: Brawdy Books. ISBN 978-0-9528344-5-8.

- Davies, E.; et al. (1987). Pembrokeshire County History. Vol. 1. Pembrokeshire Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-903771-16-0.

- Davies, B. S. (1997). Pembrokeshire Limekilns (2nd Revised ed.). St Davids: Merrivale Publications. ISBN 978-0-9515207-7-2.

- Dillon, Myles (1977). "The Irish settlements in Wales". Celtica. Vol. 12. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. pp. 1–11.

- Downes, John (2011). Folds, Faults and Fossils: Exploring geology in Pembrokeshire. Pwllheli: Llygad Gwalch Cyf. ISBN 978-1-84524-172-8.

- Fudge, Pam (2014). South West Wales Through the Lens of Harry Squibbs Pembrokeshire. Vol. 2. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-3435-7.

- Harris, P. Valentine (2011). South Pembrokeshire Dialect And Place Names. Tenby: H. G. Walters. ISBN 978-1-4474-1940-2 – via Gebert Press, Plano, TX.

- Hughes, Basil H.J. (1993) [1988]. Jottings and Historical Records with Index on the History of South Pembrokeshire. Vol. 1: 1066 - 1389 (3 ed.). Pennar Publications. ISBN 978-1-898687-00-9.

- Hughes, Basil H.J. (2014). "Pembrokeshire Parishes, Places & People. Castlemartin Hundred". archive.org.

- James, J. Ivor (1968). Molleston Baptist Church-Reflections on the Founders' Tercentenary (First ed.). Carmarthen: V.G. Lodwick & Sons Ltd. ASIN B00J1IHH9Y.

- Jenkins, J. Geraint (2016). Pembrokeshire, its present and its past Explored. Pwllheli: Llygad Gwalch Cyf. ISBN 978-1-84524-246-6.

- John, Brian S. (1998). The Geology of Pembrokeshire. Cardigan: Abercastle Publications. ISBN 978-1-872887-20-3.

- Jones, Francis (1996). Innes-Smith, Robert (ed.). Historic Houses of Pembrokeshire and Their Families (First ed.). Dinas: Brawdy Books. ISBN 978-0-9528344-0-3.

- Laws, Edward (1888). The History of Little England Beyond Wales. London: George Bell.

- Lloyd, Thomas; Orbach, Julian; Scourfield, Robert (2004). Pembrokeshire: The Buildings of Wales (Pevsner Architectural Guides: Buildings of Wales) (First ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10178-2.

- Lockley, Ronald Mathias (1969). The Regional Books: Pembrokeshire (2nd ed.). London: Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-7091-0781-1.

- Owen, George of Henllys (1796) [First published 1603]. A History of Pembrokeshire. With additions and observations by John Lewis of Manarnawan. London. pp. 53–230 – via Cambrian Register, Volume 2.

- Thornhill-Timmins, H. (1895). Nooks and Corners of Pembrokeshire. London: Elliot Stock.

- Willison, Christine (2013). Pembrokeshire Folk Tales. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6565-4.

External links

[edit]- Historical information about Pembrokeshire on GENUKI

- Pembrokeshire County Council

- Visit Pembrokeshire (official council tourism website)

- Pembrokeshire Cultural Services (archives, libraries, museums)

- Pembrokeshire Historical Society: Pembrokeshire Antiquarians

- 19th century Ordnance Survey maps, page 1 and page 2

- List of documents and collections held at Pembrokeshire Archives and Local Studies

- Iolo's Pembrokeshire: BBC Documentary series by Iolo Williams