State of Pasundan

State of Pasundan Negara Pasundan ᮕᮞᮥᮔ᮪ᮓᮔ᮪ | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1948–1950 | |||||||||

| Motto: Gemah Ripah, Pasir Wukir, Loh Djinawi (Sundanese) (Prosperity and joy from the ocean to the mountains makes everybody thriving and longliving) | |||||||||

| Anthem: Indonesia Raya[2] | |||||||||

| Status | Dutch-sponsored state (1948–1949) Constituent state of the United States of Indonesia (1949–1950) | ||||||||

| Capital | Bandoeng | ||||||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | ||||||||

| Head of State | |||||||||

• 1948–1950 | R. A. A. Wiranatakusumah | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1948–1949 | Adil Poeradiredja | ||||||||

• 1949–1950 | Djumhana Wiriaatmadja | ||||||||

• 1950 | Anwar Tjokroaminoto | ||||||||

| Legislature | Parliament of Pasundan | ||||||||

| Historical era | Aftermath of World War II/Indonesian National Revolution | ||||||||

| 26 February 1948 | |||||||||

| 27 December 1949 | |||||||||

| 22–23 January 1950 | |||||||||

• Dissolved | 11 March 1950 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

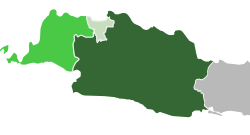

The State of Pasundan (Indonesian: Negara Pasundan; Sundanese: Nagara Pasundan) was a federal state (negara bagian) formed in the western part of the Indonesian island of Java by the Netherlands in 1948 following the Linggadjati Agreement. It was similar to the geographical area now encompassed by the current provinces of West Java, Banten and Jakarta.

A Pasundan Republic (Indonesian: Republik Pasundan) was declared on 4 May 1947 but was dissolved later that year. On 26 February 1948, the State of West Java (Negara Jawa Barat) was established and, on 24 April 1948, the state was renamed Pasundan. Pasundan became a federal state of the United States of Indonesia in 1949 but was incorporated into the Republic of Indonesia (itself also a constituent of the USI) on 11 March 1950.[3][4]

In 2009, there was a proposal to rename the present West Java province Pasundan ("Province of the Sundanese") after the historical name for West Java.[5]

Background

[edit]Indonesian developments

[edit]On 17 August 1945, Sukarno proclaimed the independence of Indonesia, which had been a Dutch colony, and then had been occupied by the Japanese since 1942. The Dutch wished to retain control, and an armed conflict broke out.[6][7] In November 1946, following international pressure, the Indonesians and Dutch signed the Linggadjati Agreement, in which the Dutch recognized Indonesian de facto authority over Java and Sumatra and both sides agreed to cooperate in the establishment of a United States of Indonesia comprising the Republic, Borneo and eastern Indonesia. However the Dutch began creating federal states unilaterally, beginning with the State of East Indonesia in December 1946. By July 1947, the cost to the Dutch of maintaining military forces in Indonesia and the desire to regain access to the resources of Java and Sumatra led the decision to attack the Republic. At midnight on 30 July 1947, the Dutch launched a "Police Action", and took control of West Java and Madura as well as the areas around Semarang, Medan and Palembang. [8][9][10][11]

Suriakartalegawa's Pasundan Republic

[edit]The first attempt at establishing an independent republican State of Pasundan was by a Sundanese aristocrat named Musa Suriakartalegawa, who later claimed that it was at the suggestion of the political adviser to Dutch East Indies Lieutenant Governor Hubertus van Mook.[12] He began laying the foundations of the republic by establishing the Pasundan People's Party (Partai Rakyat Pasundan, PRP) on 18 November 1946, with Raden Sadikin as the chairman of the party.[13] Raden Sadikin, an employee of a Dutch food distribution centre in North Bandung, was chosen as the chairman of the party due to Kartalegawa's low reputation. Suriakartalegawa himself was not sympathetic to the Indonesian national movement.[14] The party itself was established as a response to the lack of Sundanese representation in the Malino Conference and Pangkalpinang Conference.[15] As secretary and treasurer of the party, two men who had been a chauffeur before the war and garden foremen during the Japanese occupation were appointed. Party membership was done by ‘subtle coercion’.[14] Kartalegawa sought to realise a Pasundan Republic independent of Indonesia. This effort was supported by the Dutch Resident in Bandung, M. Klaassen, who wrote a report, dated 27 December 1946. The Preanger resident wrote in his report, that for centuries, there had been Sundanese-Javanese ethnic rivalry, due to differences in customs, traditions and mentality. Indonesia had always been led by the Javanese, so the PRP was seen as a spontaneous popular movement. Klaassen expressed satisfaction with the rise of this anti-republican movement in Tatar Pasundan, advocating for Dutch support, though he harbored concerns about certain PRP members who he believed were motivated by personal gain rather than genuine regional loyalty. Whist governor Abbenhuis shared Klaassen's view and backing, Dr. Hubertus van Mook, the Dutch High Commissioner of the Dutch East Indies, opposed backing the movement.

Using the party as the base of support, Suriakartalegawa established the State of Pasundan in the small areas of West Java still controlled by the Dutch. On May 4, 1947, he proclaimed the establishment of the Pasundan State at a large gathering in Bandung, attended by approximately 5,000 people.[16] Dutch military forces provided trucks to transport people to the proclamation site and during the ceremony, Dutch military police officers presented attendees with Pasundan flags and bread to encourage them to parade in support of the republic. Suriakartalegawa appointed himself as the president and Koestomo as the prime minister in a provisional government. The Dutch supported Suriakartalegawa by providing facilities such as the press and radio, while the Enlightenment Service of the Dutch helped to spread propaganda pamphlets of the PRP.[17][18][19] Its implementation was assisted by Dutch military intelligence, Netherlands East Indies Forces Intelligence Service (NEFIS). Although Van Mook had prohibited such actions, local Dutch officials provided logistical support, transporting Kartalegawa's followers to Bogor, where they were welcomed by Colonel Thompson and Resident Statius Muller.[16]

The establishment of the state was denounced by Sundanese aristocrats and commoners and did not lessen people's support for the Republic of Indonesia. Wiranatakusumah and his family sent out a wire to Sukarno on 6 May 1947 that opposed the establishment of the State of Pasundan.[20][21] At the time, Soekarno was still supported by many people and Kartalegawa was considered a defector. But this did not prevent Kartalegawa from launching a movement in Bogor in May 1947, occupying offices and stations and even taking a resident prisoner. The PRP case was a political upheaval that illustrated the situation after Military Aggression, July 1947, in Tatar Sunda. Public meetings were held throughout West Java to oppose the formation of the state, and the Indonesian army in Garut announced IDR 10,000 bounty for the capture of Suriakartalegawa, either dead or alive. Suriakartalegawa's son and mother spoke out against the formation of the state on the Indonesian Radio Republik Indonesia.[22]

Following press reports of the farcical nature of the state, and noticing the lack of support for it, the Netherlands Government Information Service withdrew its support. Suriakartalegawa's republic practically disappeared after the July 1947 Dutch "Police Action". The establishment of Pasundan convinced the Republican side of the Dutch intention to "divide and rule" and maintain their control over Indonesia.[22][23]

West Java Conferences

[edit]

Following the "Police Action", the Dutch authorities established an organization to administer the areas they had gained control over. This was headed by a Government Commissioner for Administrative Affairs (Dutch: Regeringscommissarissen vor Bestuursaangelegenheden (Recomba)). The West Java Recomba organized a series of conferences involving various groups in West Java to establish a new State of Pasundan. Three conferences were held, all in the city of Bandung.[21][24]

The first conference was held from 13 until 18 November 1947. It was attended by 50 delegates from all of the regions of West Java and discussed matters regarding the government of the State of Pasundan, the integration between Dutch and Indonesian officials, and efforts to restore peace and security in West Java.[25] The conference managed to form a liaison committee between the Dutch and the Indonesian officials, headed by Hilman Djajadiningrat (then Governor of Jakarta).[26]

The next conference was held a month later, from 16 until 20 December 1947. A larger number of delegates (170 delegates) attended. Instead of representing the Sundanese people only, the delegates also came from minorities in West Java (Chinese, Arabic, Europeans, Indo people).[27] Five more people were appointed to the liaison committee, three of which represented minorities. The liaison committee was renamed the preparatory committee.[28]

There were three opinions regarding the formation of the State of Pasundan. The majority of the delegates opted to establish a definitive government, while the others (mainly pro-Indonesian) opted for transitional government or refused to form a government until a referendum was held.[29] Three motions were submitted to the conference by the delegates. Even though these motions had differences, they were seen as all having a common aim, and following negotiations, they were combined in the form of a resolution stating that the next conference should form a provisional government for West Java with a parliament.[30]

In January 1948, following international pressure, Indonesian Republicans and the Dutch signed the Renville Agreement, which recognized Dutch authority over Indonesia pending the handing over of sovereignty to a United States of Indonesia (USI), of which the Republic of Indonesia would be one component. Regions would be given the option to decide whether to join the USI or the Republic of Indonesia. The agreement also led to the division of Java into areas of Dutch and Republic of Indonesia control separated by a ceasefire line known as the van Mook Line. The Pasundan region was within the Dutch-controlled area.[31][32]

The final West Java conference, the third, was held from 23 February until 5 March 1948. Of the 100 delegates, 53 were chosen by indirect election, and 43 appointed by the Dutch. Most of these delegates were pro-Indonesia, and a particularly vocal nationalist minority expressed its opposition to the establishment of a separate state without a referendum - as specified in the Renville Agreement. At this conference, republican R. A. A. Wiranatakusumah, who had served in Indonesia's first cabinet, was narrowly elected head of state, or wali negara, and the head of the pro-republican faction, Adil Poeradiredja, was elected prime minister. The delegates to the conference subsequently became the Pasundan parliament.[33][34]

Establishment of the State of Pasundan

[edit]

On 26 February 1948, the Dutch East Indies government expressed approval of the resolution establishing a provisional West Java government, subsequently renamed Pasundan, and the state came into being.[35] The cabinet was sworn in on 8 May. The Indonesians supporting the state were those dissatisfied with their positions within the Republic of Indonesia or who believed that the republic would not survive and wanted to protect the interests of the ethnic Sundanese people within a Sundanese state in a Dutch-supported federal state. However, support for the Indonesian Republic was so strong among the members of the parliament and the cabinet, that the Dutch authorities in Batavia felt obliged to control many aspects of Pasundan life and restrict civil liberties, including the right of assembly. Some powers were transferred to the Pasundan government, but these were severely limited, and the Dutch even kept control of secondary and higher education, as well as the radio, newspapers and information offices.[36]

On 19 December 1948, the Dutch launched a second "Police Action" against the areas controlled by the Republic. Dutch forces captured the republican capital, Yogyakarta and detained President Sukarno. In protest, the Pasundan cabinet, along with the cabinet of the largest federal state, the State of East Indonesia, resigned, to the embarrassment of the Dutch, who had planned a conference to discuss the form of the federal Indonesian state. Prime Minister Adil Poeradiredja refused to form a new cabinet, and its 6-member replacement was formed by Djumhana Wiriaatmadja. However, the new cabinet's anti-Dutch stance angered the Batavia administration, which threatened to arrest key members of the government and install a military government. Four members of the cabinet subsequently resigned, as did Djumhana on 28 January 1949. He then formed a cabinet more acceptable to the Dutch. In early March 1949, Prime Minister Djumhana was part of the Federal Consultative Assembly delegation, representing the non-Republican Indonesian states, that took part in negotiations with Indonesian president Sukarno and other senior officials on the island of Bangka, where Sukarno had been exiled by the Dutch. Both parties to these negotiations, together with the Dutch, then took part in the Dutch–Indonesian Round Table Conference in the Hague from August to November. This conference led to the Dutch transferring sovereignty to the United States of Indonesia, with Pasundan as one component of it, on 27 December.[37][38][39]

Dissolution

[edit]The Dutch-sponsored Pasundan government was never in control of the entire area that officially constituted the state. At the time of its establishment, around 25 percent of the area was in the hands of Islamic anti-Dutch groups, including Darul Islam. Even following the second Dutch "police action" launched against the Republic in December 1948, only one-third of the state was controlled by the Dutch.[40]

On 23 January 1950, Raymond Westerling's Legion of the Just Ruler (APRA) launched a coup attempt. They occupied key locations in Bandung and then headed for Jakarta to attack the United States of Indonesia Cabinet. The coup failed, but the fact that it had been launched from Pasundan, and that several Pasundan leaders were arrested for their involvement, severely damaged the credibility of the state. On 9 February, a day after the USI cabinet passed an emergency law transferring the authority of the Pasundan government to a State Commissioner for Pasundan, Wiranatakusumah handed over his powers. The following month, Pasundan and a number of other states requested they be merged into the Republic of Indonesia. On 11 March 1950, the state of Pasundan became part of the Republic and ceased to exist as a separate entity.[7][41][42]

See also

[edit]- History of Indonesia

- Indonesian National Revolution

- Indonesian regions

- Djerman Prawirawinata last Minister of State of Pasundan

- Mohammad Enoch Pasundan senator

Notes

[edit]- ^ The flag of the Negara Jawa Barat (State of West Java), later renamed to Negara Pasundan (Sundanese State) used from 1948‒1950. A precursor design of the White and Green were used for Suriakartalegawa's Pasundan Republic. However, it was unrecognized and was dissolved.

- ^ Under federal government but governor appointed by the Wali Negara of Pasundan.

- ^ From 30 December 1949 until 11 March 1950 as Jakarta Federal District.

- ^ Claimed by the State of Pasundan but uncontrolled.

References

[edit]- ^ Kasputra, Danil (2023-03-09). "Selayang Pandang Eksistensi Negara Pasundan Bikinan Belanda". Romansa Bandung. Retrieved 2024-09-15.

- ^ ""Indonesia Raja" Pasundans volkslied". Het nieuwsblad voor Sumatra. 21 April 1949.

- ^ "United States of Indonesia".

- ^ Simanjuntak 2003, pp. 99–100

- ^ Nasrullah, Annas (2009-10-29). "Tokoh Jabar Siapkan Deklarasi Provinsi Pasundan : Okezone News". Okezone (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-03-21.

- ^ Reid 1974, p. 28

- ^ a b Ricklefs 2008, pp. 341–344

- ^ Reid 1974, p. 110

- ^ Ricklefs 2008, p. 361

- ^ Ricklefs 2008, pp. 362–363

- ^ Reid 1974, pp. 111–112

- ^ Kahin 1952, pp. 108–109

- ^ Mulyana 2015, p. 66

- ^ a b Handayani, Maulida Sri. "Berakhirnya Negara Pasundan". tirto.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ Mulyana 2015, p. 67

- ^ a b Handayani, Maulida Sri. "Berakhirnya Negara Pasundan". tirto.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ Mulyana 2015, pp. 68–69

- ^ Kahin 1952, p. 238

- ^ Wolf 2007, pp. 108–109

- ^ Helius et al. 1992, p. 32

- ^ a b Kahin 1952, p. 239

- ^ a b Helius et al. 1992, p. 33

- ^ Wolf 2007, p. 109

- ^ Schiller 1955, pp. 74–75

- ^ Tuhuteru 1948, p. 1

- ^ Tuhuteru 1948, p. 2

- ^ Tuhuteru 1948, p. 6

- ^ Tuhuteru 1948, p. 7

- ^ Helius et al. 1992, p. 36

- ^ Tuhuteru 1948, p. 14

- ^ Kahin 1952, pp. 369

- ^ Ricklefs 2008, p. 364

- ^ Helius et al. 1992, pp. 42–43

- ^ Reid 1974, pp. 226, 233

- ^ Kahin 1952, pp. 244–245

- ^ Kahin 1952, pp. 369–374

- ^ Kahin 1952, pp. 374–377, 444

- ^ Ricklefs 2008, pp. 369–370

- ^ Agung 1996, p. 514

- ^ Kahin 1952, p. 369

- ^ Kahin 1952, p. 455

- ^ Schiller 1955, pp. 339, 432

Bibliography

[edit]- Agung, Ide Anak Agung Gde (1996) [1995]. From the Formation of the State of East Indonesia Towards the Establishment of the United States of Indonesia. Translated by Owens, Linda. Yayasan Obor. ISBN 978-979-461-216-3.

- Bastiaans, W.Ch.J. (1950). Personalia van Staatkundige Eenheden (Regering en Volksvertegenwoordiging) in Indonesie. Djakarta: Kementerian Penerangan.

- Kahin, George McTurnan (1952). Nationalism and Revolution in Indonesia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Helius, Sjamsuddin; Ekadjati, Edi S.; Marlina, Kuswiah; Wiwi, Ietje (1992). Menuju Negara Kesatuan: Negara Pasundan. Jakarta: Ministry of Education and Culture.

- Mulyana, Agus (2015). Negara Pasundan 1947-1950: Gejolak Menak Sunda Menuju Integrasi Nasional (in Indonesian). Yogyakarta: Penerbit Ombak. ISBN 9786022583011.

- Reid, Anthony J.S (1974), The Indonesian National Revolution, 1945-1950, Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia: Longman, ISBN 0-582-71047-2

- Ricklefs, M.C. (2008) [1981], A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1200 (4th ed.), Palgrave MacMillan, ISBN 978-0-230-54686-8

- Schiller, A. Arthur (1955), The Formation of Federal Indonesia 1945-1949, The Hague: W. van Hoeve Ltd

- Simanjuntak, P. N. H. (2003). Kabinet-Kabinet Republik Indonesia: Dari Awal Kemerdekaan Sampai Reformasi (in Indonesian). Jakarta: Djambatan. ISBN 979-428-499-8.

- Tuhuteru, J.M.A. (1948). Riwajat Singkat Terdirinja Negara Pasoendan. Jakarta: Government Information Office.

- Wolf, Charles (2007) [1948]. The Indonesian Story - The Birth, Growth And Structure of The indonesian Republic. France Press. ISBN 9781406713312.