Papyrus: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 216.120.170.163 to last version by VoABot II (HG) |

|||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

==Documents written on papyrus == |

==Documents written on papyrus == |

||

All of this is bull-shit. |

|||

The word for the material ''papyrus'' is also used to designate documents written on sheets of it, often rolled up into scrolls. The plural for such documents is ''papyri''. Historical papyri are given identifying names—generally the name of the discoverer, first owner or institution where it is kept—and numbered, such as "[[Papyrus Harris I]]". Often an abbreviated form is used such as "pHarris I". |

The word for the material ''papyrus'' is also used to designate documents written on sheets of it, often rolled up into scrolls. The plural for such documents is ''papyri''. Historical papyri are given identifying names—generally the name of the discoverer, first owner or institution where it is kept—and numbered, such as "[[Papyrus Harris I]]". Often an abbreviated form is used such as "pHarris I". |

||

Revision as of 14:14, 19 September 2008

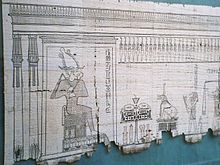

Papyrus (/pəˈpaɪrəs/) (Rhymes: -aɪrəs) is a thick paper-like material produced from the pith of the papyrus plant, Cyperus papyrus, a wetland sedge that was once abundant in the Nile Delta of Egypt. Papyrus usually grow 2–3 meters (5–9 ft) tall. Papyrus is first known to have been used in ancient Egypt (at least as far back as the First dynasty), but it was also used throughout the Mediterranean region. Ancient Egypt used this plant for boats, mattresses, mats and paper.

History

In the first centuries BC and AD, papyrus scrolls gained a rival as a writing surface in the form of parchment, which was prepared from animal skins. Sheets of parchment were folded to form quires from which book-form codices were fashioned. Early Christian writers soon adopted the codex form, and in the Græco-Roman world it became common to cut sheets from papyrus rolls in order to form codices.

Codices were an improvement on the papyrus scroll as the papyrus was not flexible enough to fold without cracking and a long roll, or scroll, was required to create large volume texts. Papyrus had the advantage of being relatively cheap and easy to produce, but it was fragile and susceptible to both moisture and excessive dryness. Unless the papyrus was of good quality, the writing surface was irregular, and the range of media that could be used was also limited.

By AD 800 the use of parchment and vellum had replaced papyrus in many areas, though its use in Egypt continued until it was replaced by more inexpensive paper introduced by Arabs. The reasons for this switch include the significantly higher durability of the hide-derived materials, particularly in moist climates, and the fact that they can be manufactured anywhere. The latest certain dates for the use of papyrus are 1057 for a papal decree (typically conservative, all papal "bulls" were on papyrus until 1022) and 1087 for an Arabic document. Papyrus was used as late as the 1100s in the Byzantine Empire, but there are no surviving examples. Although its uses had transferred to parchment, papyrus therefore just overlapped with the use of paper in Europe, which began in the 11th century.

Etymology

The English word papyrus derives, via Latin, from Greek πάπυρος papyros. Greek has a second word for papyrus, βύβλος byblos (said to derive from the name of the Phoenician city of Byblos). The Greek writer Theophrastus, who flourished during the 4th century BC, uses papuros when referring to the plant used as a foodstuff and bublos for the same plant when used for non-food products, such as cordage, basketry, or a writing surface. The more specific term βίβλος biblos, which finds its way into English in such words as bibliography, bibliophile, and bible, refers to the inner bark of the papyrus plant. Papyrus is also the etymon of paper, a similar substance.

It is often claimed that Egyptians referred to papyrus as pa-per-aa [p3y pr-ˁ3] (lit., "that which is of Pharaoh"), apparently denoting that the Egyptian crown owned a monopoly on papyrus production. However no actual ancient text using this term is known. In the Egyptian language, papyrus was known by the terms wadj [w3ḏ], tjufy [ṯwfy], and djet [ḏt]. The Greek word papyros has no known relationship to any Egyptian word or phrase.

Documents written on papyrus

All of this is bull-shit. The word for the material papyrus is also used to designate documents written on sheets of it, often rolled up into scrolls. The plural for such documents is papyri. Historical papyri are given identifying names—generally the name of the discoverer, first owner or institution where it is kept—and numbered, such as "Papyrus Harris I". Often an abbreviated form is used such as "pHarris I".

Manufacture and use

Papyrus is made from the stem of the plant. The outer rind is first stripped off, and the sticky fibrous inner pith is cut lengthwise into thin strips of about 40 cm long. The strips are then placed side by side on a hard surface with their edges slightly overlapping, and then another layer of strips is laid on top at a right angle. The strips may have been soaked in water long enough for decomposition to begin, perhaps increasing adhesion, but this is not certain. While still moist, the two layers are hammered together, mashing the layers into a single sheet. The sheet is then dried under pressure. After drying, the sheet of papyrus is polished with some rounded object, possibly a stone or seashell or round hard wood.

To form the long strip that a scroll required, a number of such sheets were united, placed so that all the horizontal fibres parallel with the roll's length were on one side and all the vertical fibres on the other. Normally, texts were first written on the recto, the lines following the fibres, parallel to the long edges of the scroll. Secondarily, papyrus was often reused, writing across the fibres on the verso [1] Pliny the Elder describes the methods of preparing papyrus in his Naturalis Historia.

In a dry climate like that of Egypt, papyrus is stable, formed as it is of highly rot-resistant cellulose; but storage in humid conditions can result in molds attacking and destroying the material. In European conditions, papyrus seems only to have lasted a matter of decades; a 200–year-old papyrus was considered extraordinary. Imported papyrus that was once commonplace in Greece and Italy has since deteriorated beyond repair, but papyrus is still being found in Egypt; extraordinary examples include the Elephantine papyri and the famous finds at Oxyrhynchus and Nag Hammadi. The Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum, containing the library of Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, Julius Caesar's father-in-law, was preserved by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, but has only been partially excavated.

There have been sporadic attempts to revive the manufacture of papyrus during the past 250 years. The Scottish explorer James Bruce experimented in the late eighteenth century with papyrus plants from the Sudan, for papyrus had become extinct in Egypt. Also in the eighteenth century, a Sicilian named Saverio Landolina manufactured papyrus at Syracuse, where papyrus plants had continued to grow in the wild. The modern technique of papyrus production used in Egypt for the tourist trade was developed in 1962 by the Egyptian engineer Hassan Ragab using plants that had been reintroduced into Egypt in 1872 from France. Both Sicily and Egypt have centres of limited papyrus production.

Papyrus is still used by communities living in the vicinity of swamps, to the extent that rural householders derive up to 75% of their income from swamp goods (Maclean et al. 2003b; c). Particularly in East and Central Africa, people harvest papyrus, which is used to manufacture items that are sold or used locally. Examples include baskets, hats, fish traps, trays or winnowing mats and floor mats. Papyrus is also used to make roofs, ceilings, rope and fences, or as fuel (Maclean 2003c). Although increasingly, alternatives such as eucalyptus are available, papyrus is still used as fuel.

See also

- Pliny the Elder

- Papyrology

- Papyrus sanitary pad

- For Egyptian papyri:

- Other papyri:

- The papyrus plant in Egyptian art

Other ancient writing materials:

- Palm leaf manuscript India

- Amate Mesoamerica

- Paper invented in Han Dynasty China

- Ostracon

- Writing boards

- Wax tablets

- Clay tablets

References

- H. Idris Bell and T.C. Skeat, 1935. "Papyrus and its uses" (British Museum pamphlet).

- Bierbrier, Morris Leonard, ed. 1986. Papyrus: Structure and Usage. British Museum Occasional Papers 60, ser. ed. Anne Marriott. London: British Museum Press.

- Černý, Jaroslav. 1952. Paper and Books in Aancient Egypt: An Inaugural Lecture Delivered at University College London, 29 May 1947. London: H. K. Lewis. (Reprinted Chicago: Ares Publishers Inc., 1977).

- Langdon, S. 2000. Papyrus and its Uses in Modern Day Russia, Vol. 1, pp. 56-59.

- Leach, Bridget, and William John Tait. 2000. "Papyrus". In Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology, edited by Paul T. Nicholson and Ian Shaw. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 227–253. Thorough technical discussion with extensive bibliography.

- Leach, Bridget, and William John Tait. 2001. "Papyrus". In The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, edited by Donald Bruce Redford. Vol. 3 of 3 vols. Oxford, New York, and Cairo: Oxford University Press and The American University in Cairo Press. 22–24.

- Parkinson, Richard Bruce, and Stephen G. J. Quirke. 1995. Papyrus. Egyptian Bookshelf. London: British Museum Press. General overview for a popular reading audience.

External links

- Leuven Homepage of Papyrus Collections

- Papyrus Institute: Homepage of the company founded by Dr. Hassan Ragab.

- Complete List of Greek NT Papyri

- Ancient Egyptian Papyrus - Aldokkan