Pan Am: Difference between revisions

Break up awkward hyphen/slash combination |

Akosiyavre (talk | contribs) Tag: repeating characters |

||

| Line 53: | Line 53: | ||

===Formation=== |

===Formation=== |

||

[[File:Tran12G7.jpg|left|thumb|[[Juan Trippe]] surveying his office globe]] |

[[File:Tran12G7.jpg|left|thumb|[[Juan Trippe]] surveying his office globe]] |

||

'''Pan American Airways, Incorporated''' (PAA) was founded as a [[Shell_corporation#Different_meaning|shell company]] <ref group=nb>publicly held company with no or nominal assets other than money</ref> on March 14, 1927, by [[United States Army Air Corps|Air Corps]] Majors [[Henry H. Arnold|Henry H. "Hap" Arnold]], [[Carl Andrew Spaatz|Carl A. Spaatz]], and John H. Jouett as a counterbalance to the [[Germany|German]]-owned [[Colombia]]n carrier [[SCADTA]],{{sfn|Daley|1980|pp=27–28}} operating in Colombia since 1920. SCADTA lobbied hard for landing rights in the [[Panama |

'''Pan American Airways, Incorporated''' (PAA) was founded as a [[Shell_corporation#Different_meaning|shell company]] <ref group=nb>publicly held company with no or nominal assets other than money</ref> on March 14, 1927, by [[United States Army Air Corps|Air Corps]] Majors [[Henry H. Arnold|Henry H. "Hap" Arnold]], [[Carl Andrew Spaatz|Carl A. Spaatz]], and John H. Jouett as a counterbalance to the [[Germany|German]]-owned [[Colombia]]n carrier [[SCADTA]],{{sfn|Daley|1980|pp=27–28}} operating in Colombia since 1920. SCADTA lobbied hard for landing rights in the [[Panama Canahgtfrdel Zone]], ostensibly to survey air routes for a connection to the United States, which the Air Corps viewed as a precursor to a possible German aerial thregfvdsdfghat to the canal. Arnold and Spaatz drew up the prospectus for Pan American when SCADTA chartered a company in [[Delaware]] to obtain air mail contracts from the [[United States|US]] government. Pan American was able to obtain the US mail delivery contract to Cuba, but lacked any aircraft to perfonhgfrerm the job and did not have landing rights in Cuba.<ref name="afm67">{{cite journal | last = Newton| first = Dr. Wesley P.| year = 1967| title = The Role of the Army Air Arm in Latin America, 1922–1931| journal=Air Power Journal| issue = September–October| url=http://www.airpower.maxwell.af.mil/airchronicles/aureview/1967/sep-oct/newton.html | accessdate =Jan 22, 2011}}</ref> |

||

On June 2, 1927, [[Juan Trippe]] formed the '''Aviation Corporation of the Americas''' (ACA) with the backing of powerful and politically connected financiers who included [[Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney]] and [[W. Averell Harriman]], and raised $250,000 in startup capital from the sale of stock.<ref>Anthony J. Mayo, Nitin Nohria and Mark Rennella, ''Entrepreneurs, Managers, and Leaders: What the Airline Industry Can Teach Us about Leadership'' (Macmillan, 2009) p49</ref> Their operation had the all-important landing rights for Havana, having acquired American International Airways, a small airline established in 1926 by John K. Montgomery and Richard B. Bevier as a [[seaplane]] service from Key West, Florida, to Havana. ACA met its deadline of having an air mail service operating by October 19, 1927, by chartering a [[Fairchild FC-2]] floatplane from a small Dominican Republic carrier, West Indian Aerial Express.<ref name="cent"/><ref>John R. Steele, "The Very Beginning" [http://panam.com/default1.asp History of Pan American World Airways: The Early Years]</ref> |

On June 2, 1927, [[Juan Trippe]] formed the '''Aviation Corporation of the Americas''' (ACA) with the backing of powerful and politically connected financiers who included [[Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney]] and [[W. Averell Harriman]], and raised $250,000 in startup capital from the sale of stock.<ref>Anthony J. Mayo, Nitin Nohria and Mark Rennella, ''Entrepreneurs, Managers, and Leaders: What the Airline Industry Can Teach Us about Leadership'' (Macmillan, 2009) p49</ref> Their operation had the all-important landing rights for Havana, having acquired American International Airways, a small airline established in 1926 by John K. Montgomery and Richard B. Bevier as a [[seaplane]] service from Key West, Florida, to Havana. ACA met its deadline of having an air mail service operating by October 19, 1927, by chartering a [[Fairchild FC-2]] floatplane from a small Dominican Republic carrier, West Indian Aerial Express.<ref name="cent"/><ref>John R. Steele, "The Very Beginning" [http://panam.com/default1.asp History of Pan American World Airways: The Early Years]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 08:22, 4 December 2011

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Founded | March 14, 1927 (as Pan American Airways PAA)) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ceased operations | December 4, 1991 | ||||||

| Hubs | |||||||

| Focus cities |

| ||||||

| Frequent-flyer program | WorldPass | ||||||

| Fleet size | 226 | ||||||

| Destinations | 86 countries on all six major continents at its peak in 1968 | ||||||

| Parent company | Pan Am Corporation | ||||||

| Headquarters | New York City Miami, Florida | ||||||

| Key people | Juan T. Trippe (CEO 1927–1968) Harold Gray (CEO 1968–1969) Najeeb E. Halaby Jr (CEO 1969–1971) William T. Seawell (CEO 1971–1981) C. Edward Acker (CEO 1981–1988) Thomas G. Plaskett (CEO 1988–1991) Russell L. Ray, Jr. (CEO 1991) | ||||||

Pan American World Airways, commonly known as Pan Am, was the principal and largest international air carrier in the United States from 1927 until its collapse on December 4, 1991. Founded in 1927 as a scheduled air mail and passenger service operating between Key West, Florida and Havana, Cuba, the airline became a major company credited with many innovations that shaped the international airline industry, including the widespread use of jet aircraft, jumbo jets, and computerized reservation systems.[1] It was also a founder member of the International Air Transport Association (IATA), the global airline industry association.[2] Identified by its blue globe logo, the use of the word "Clipper" in aircraft names and call signs, and the white pilot uniform caps, the airline was a cultural icon of the 20th century. In an era dominated by flag carriers that were wholly or majority government-owned, it was also the unofficial flag carrier of the United States. During most of the jet era, Pan Am's flagship terminal was the Worldport located at John F. Kennedy Airport in New York.[1]

History

Formation

Pan American Airways, Incorporated (PAA) was founded as a shell company [nb 1] on March 14, 1927, by Air Corps Majors Henry H. "Hap" Arnold, Carl A. Spaatz, and John H. Jouett as a counterbalance to the German-owned Colombian carrier SCADTA,[3] operating in Colombia since 1920. SCADTA lobbied hard for landing rights in the Panama Canahgtfrdel Zone, ostensibly to survey air routes for a connection to the United States, which the Air Corps viewed as a precursor to a possible German aerial thregfvdsdfghat to the canal. Arnold and Spaatz drew up the prospectus for Pan American when SCADTA chartered a company in Delaware to obtain air mail contracts from the US government. Pan American was able to obtain the US mail delivery contract to Cuba, but lacked any aircraft to perfonhgfrerm the job and did not have landing rights in Cuba.[4]

On June 2, 1927, Juan Trippe formed the Aviation Corporation of the Americas (ACA) with the backing of powerful and politically connected financiers who included Cornelius Vanderbilt Whitney and W. Averell Harriman, and raised $250,000 in startup capital from the sale of stock.[5] Their operation had the all-important landing rights for Havana, having acquired American International Airways, a small airline established in 1926 by John K. Montgomery and Richard B. Bevier as a seaplane service from Key West, Florida, to Havana. ACA met its deadline of having an air mail service operating by October 19, 1927, by chartering a Fairchild FC-2 floatplane from a small Dominican Republic carrier, West Indian Aerial Express.[6][7]

The Atlantic, Gulf, and Caribbean Airways company was established on October 11, 1927, by New York City investment banker Richard Hoyt, who served as president.[6] This company merged with PAA and ACA on June 23, 1928.[6] Richard Hoyt was named as president of the new Aviation Corporation of the Americas, but Trippe and his partners held 40% of the equity and Whitney was made president. Trippe became operational head of Pan American Airways, the new company's principal operating subsidiary.[6]

The US government approved the original Pan Am's mail delivery contract with little objection, out of fears that SCADTA would have no competition in bidding for routes between Latin America and the United States. The government further helped Pan Am by insulating it from its US competitors, seeing the airline as the "chosen instrument" for US foreign air routes.[8] The airline expanded internationally, benefiting from a virtual monopoly on foreign routes.[9]

Trippe and his associates planned to extend Pan Am's network through all of Central and South America. During the late 1920s and early 1930s, Pan Am purchased a number of ailing or defunct airlines in Central and South America and negotiated with postal officials to win most of the government's airmail contracts to the region. In September 1929, Trippe toured Latin America with Charles Lindbergh to negotiate landing rights in a number of countries, including SCADTA's home turf of Colombia. By the end of the year, Pan Am offered flights along the west coast of South America to Peru. The following year, Pan Am purchased the New York, Rio, and Buenos Aires Line, giving it a seaplane route along the east coast of South America to Buenos Aires, Argentina, and westbound to Santiago, Chile. Its Brazilian subsidiary NYRBA do Brasil was later renamed as Panair do Brasil.[10] Pan Am also partnered with Grace Shipping Company in 1929 to form Pan American-Grace Airways, better known as Panagra, to gain a foothold to destinations in South America.[6]

Pan Am's holding company, the Aviation Corporation of the Americas, was one of the most sought after stocks on the New York Curb Exchange in 1929, and flurries of speculation surrounded each of its new route awards. In April 1929, Trippe and his associates reached an agreement with United Aircraft and Transport Corporation (UATC) to segregate Pan Am operations to south of the Mexico – United States border, in exchange for UATC taking a large shareholder stake (UATC was the parent company of what are now Boeing, Pratt & Whitney, and United Airlines).[11][12] The Aviation Corporation of the Americas changed its name to Pan American Airways Corporation in 1931.

Flight crews

Critical to Pan Am's success as an airline was the proficiency of its flight crews, who were rigorously trained in long-distance flight, seaplane anchorage and berthing operations, over-water navigation, radio procedure, aircraft repair, and marine tides.[13] During the day, use of the compass while judging drift from sea currents was normal procedure; at night, all flight crews were trained to use celestial navigation. In bad weather, pilots used dead reckoning and timed turns, making successful landings at fogged-in harbors by landing out to sea, then taxiing the plane into port. Many pilots had merchant marine certifications and radio licenses as well as pilot certificates.[14][15] A Pan Am flight captain would normally begin his career years earlier as a radio operator or even mechanic, steadily gaining his licenses and working his way up the flight crew roster to navigator, second officer, and first officer. Before the war, it was not unusual to see a Pan Am first officer or captain changing a cylinder head or other engine part while the plane rocked at a floating berth in a remote anchorage.[16]

Pan Am's mechanics and support staff were similarly trained. Newly hired applicants were frequently paired with experienced flight mechanics in several areas of the company until they had achieved proficiency in all aircraft types.[17] Emphasis was placed on learning to maintain and overhaul aircraft in harsh seaborne environments when faced with logistical difficulties, as might be expected in a small foreign port without an aviation infrastructure or even an adequate road network. Many crews supported repair operations by flying in spare parts to planes stranded overseas, in some cases performing repairs themselves.[16]

Clipper era

Pan Am inaugurated its South American routes using Sikorsky S-38 and S-40 flying boats. The latter were three large passenger craft put in service by Trippe in 1931 to provide greater carrying capacity than the eight-passenger S-38. Carrying the nicknames American Clipper, Southern Clipper, and Caribbean Clipper, they were the first of the series of 28 Clippers that came to symbolize Pan Am between 1931 and 1946.

In 1937 Pan Am turned to Britain and France to begin seaplane service between the United States and Europe. Pan Am reached an agreement with both countries to offer service from Norfolk, Virginia, to Europe via Bermuda and the Azores using the S-40s. Starting in June 1937, a joint service from the US mainland to Bermuda was inaugurated, with Pan Am using Sikorsky flying boats and Imperial Airways using the C class flying boat RMA Cavalier.[18]

On July 5, 1937 the first commercial survey flights across the North Atlantic were conducted.[19] The Pan Am Clipper III, a Sikorsky S-42, landed at Botwood in the Bay of Exploits in Newfoundland from Port Washington, New York, via Shediac, New Brunswick. The next day Pan Am Clipper III left Botwood for Foynes in Ireland. The same day, a Short Empire C-Class flying boat, the Caledonia, left Foynes for Botwood, and landed July 6, 1937, reaching Montreal on July 8 and New York on July 9. These test flights marked the first steps toward the beginning of commercial transatlantic flights.[19]

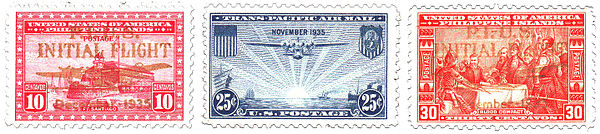

Trippe then decided to start a service from San Francisco to Honolulu, and from there to Hong Kong and Auckland following existing steamship routes. After negotiating traffic rights in 1934 to land at Pearl Harbor, Midway Island, Wake Island, Guam, and Subic Bay (Manila),[21] Pan Am shipped $500,000 worth of aeronautical equipment westward in March 1935 using the North Haven a 15,000 ton merchant ship it chartered for the purpose of provisioning each island that the clippers would stop at on their 4 to 5 day flight.[22] Pan Am ran its first survey flight to Honolulu in April 1935 with a Sikorsky S-42 flying boat.[23] The airline won the contract for a San Francisco – Canton mail route later that year and operated its first commercial flight carrying mail and express in a Martin M-130 from Alameda to Manila amid massive media fanfare on November 22, 1935. The five-leg, 8,000-mile (12,875 km) flight arrived in Manila on November 29 and returned to San Francisco on December 6, cutting the one way travel time in either direction between the two cities via the fastest scheduled steamship service by over two weeks.[24] (Both the United States and Philippine Islands issued special stamps for the two flights.) The first passenger flight over this route left Alameda on October 21, 1936.[25] The fare from San Francisco to both Manila and Hong Kong in 1937 was $950 one way (approximately $14,700 in 2010) and $1,710 round trip (approximately $26,400).[26]

On August 6, 1937 Juan Trippe accepted US aviation's highest annual prize, the Collier Trophy, on behalf of PAA from President Franklin D. Roosevelt for the company's "establishment of the transpacific airline and the successful execution of extended overwater navigation and the regular operations thereof."[27] Later, Pan Am used Boeing 314 flying boats for the Pacific route: in China, passengers could connect to domestic flights on the Pan Am-operated China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC) network, co-owned with the Chinese government. Pan Am flew to Singapore for the first time in 1941, starting a semi-monthly service which reduced San Francisco–Singapore travel times from 25 days to six days.[28] The Boeing 314s were used on transatlantic routes starting in 1939.[9]

A fleet of six large, long-range Boeing 314 flying boats was delivered to Pan Am in early 1939. The new type enabled commencement of a regular weekly transatlantic passenger and air mail service between the United States and Britain on June 24, 1939. The route was from New York via Shediac, Botwood, and Foynes to Southampton. After the outbreak of World War II, the terminal became Foynes until the service ceased for the winter on October 5; transatlantic service to Lisbon via the Azores continued into 1941. Throughout the war, Pan Am flew over 90 million miles worldwide in support of military operations.[9]

In 1940 Pan Am and TWA began using the Boeing 307 Stratoliner for passenger services. It was the first pressurized airliner to go into commercial service and the first to include a flight engineer as a member of the crew. The Boeing 307's airline service proved short-lived, as all five models built were commandeered for military service at the outbreak of World War II.[29]

The "Clippers" — the name hearkened back to the 19th century clipper ships — were the only American passenger aircraft of the time capable of intercontinental travel. To compete with ocean liners, the airline offered first-class seats on such flights, and the style of flight crews became more formal. Instead of being leather-jacketed, silk-scarved airmail pilots, the crews of the "Clippers" wore naval-style uniforms and adopted a set procession when boarding the aircraft.[30] The China Clipper became well-known for its South Seas routings.[31]

In 1942, while waiting at Foynes, County Limerick, Ireland for a Pan Am Clipper flight to New York, passengers were served a drink today known as Irish coffee by Chef Joe Sheridan.[32]

During World War II most of the Clippers were pressed into the military. During this era Pan Am pioneered a new air route across Western and Central Africa to Iran, and in early 1942 the airline became the first to operate a route circumnavigating the globe. Another first occurred in January 1943, when Franklin D. Roosevelt became the first US president to fly abroad, in the Dixie Clipper.[33] It was also during this period that Star Trek creator Gene Roddenberry was a Clipper pilot. He was aboard the Clipper Eclipse when it crashed in Syria on June 19, 1947.[34]

Postwar developments

Air transport's growing importance in the post-war era meant that Pan Am would no longer enjoy the official patronage it had been afforded in pre-war days to prevent the emergence of any meaningful competition, both at home and abroad.[35]

Although Pan Am continued to use its considerable political influence to lobby for protection of its position as America's primary international airline, it encountered increasing competition — first from American Export Airlines (American Overseas Airlines (AOA) from November 1945[36]) across the Atlantic to Europe, and subsequently from others including TWA to Europe, Braniff to South America, United to Hawaii and Northwest Orient to East Asia, as well as five potential rivals to Mexico. This changed situation resulted from a more enlightened approach of the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) towards the promotion of competition between major US carriers on key domestic and international scheduled routes compared with pre-war US aviation policy.[37][35][38]

AOA was the first airline to begin regular landplane flights across the Atlantic, on October 24, 1945. In January 1946 Pan Am scheduled seven DC-4s a week east from LaGuardia Airport, five to London (i.e. Hurn) and two to Lisbon. Time to Hurn was 17 hours 40 minutes including stops, and 20 hours 45 minutes to Lisbon. A Boeing 314 flying boat flew LaGuardia to Lisbon once every two weeks in 29 hours 30 minutes; flying boat flights ended shortly thereafter.[nb 2]

TWA's transatlantic challenge — the impending introduction of its faster, pressurized Lockheed Constellations — resulted in Pan Am ordering its own Constellation fleet at $750,000 apiece. Pan Am began transatlantic Constellation flights on January 14, 1946, beating TWA by three weeks.[35]

In June 1947 Pan Am started the first scheduled round-the-world airline flight. In September the weekly DC-4 was scheduled to leave San Francisco at 2200 Thursday as Flight 1, stopping at Honolulu, Midway, Wake, Guam, Manila, Bangkok and arriving in Calcutta on Monday at 1245, where it met Flight 2, a Constellation that had left New York at 2330 Friday. The DC-4 returned to San Francisco as Flight 2; the Constellation left Calcutta 1330 Tuesday, stopped at Karachi, Istanbul, London, Shannon, Gander, and arrived LaGuardia Thursday at 1455. A few months later PA 3 took over the Manila route while PA 1 shifted to Tokyo and Shanghai; Tokyo and London were always on Flight 1's route thereafter. All Pan Am round-the-world flights included at least one change of plane until Boeing 707s took over in 1960. PA 1 became daily in 1962-63, making different en route stops on different days of the week. When Boeing 747s finished replacing 707s in 1971, all stops except Tehran and Karachi were served daily in both directions. For a year or so in 1975-76 Pan Am finally completed the round-the-world trip, New York to New York.[39]

In January 1946 Miami to Buenos Aires took 71 hours 15 minutes in a Pan Am DC-3, but the following summer DC-4s flew Idlewild to Buenos Aires in 38 hr 30 min. In January 1958 Pan Am's DC-7B flew New York to Buenos Aires in 25 hours 20 minutes, while the National - Pan Am - Panagra DC-7B via Panama and Lima took 22 hours 45 minutes.[40] Convair 240s replaced DC-3s and other pre-war types on Pan Am's shorter flights in the Caribbean and South America. Pan Am also acquired a few Curtiss C-46s for an all-freight network that eventually extended to Buenos Aires.[38]

In January 1946 Pan Am had no transpacific flights beyond Hawaii, but they soon resumed, with DC-4s. In January 1958 the California to Tokyo flight was a daily Stratocruiser that took 31 hours 45 minutes from San Francisco or 32 hours 15 minutes from Los Angeles. (A flight to Seattle and a connection to Northwest's DC-7C totalled 24 hours 13 minutes from San Francisco, but Pan Am was not allowed to fly that route.)[40] The Stratocruisers' double-deck fuselage with sleeping berths and a lower-deck lounge helped it compete with its rival. Modified Stratocruisers with additional fuel tanks went into service on Pan Am's transatlantic routes in November 1954; the aim was to reliably fly nonstop New York to London and return with one stop instead of two.

In 1943-44 the airline had begun calling itself Pan American World Airways and in January 1950 Pan American Airways Corporation officially became Pan American World Airways, Inc.[41][42] In September of that year Pan Am completed the $17.45 million purchase of American Overseas Airlines from American Airlines.[35] That month Pan Am also ordered 45 Douglas DC-6Bs. The first of these, Clipper Liberty Bell (N6518C),[43] inaugurated Pan Am's all-tourist class Rainbow service between New York and London on May 1, 1952 to complement the all-first President Stratocruiser service.[42] From June 27, 1960 DC-6Bs also began replacing DC-4s on Pan Am's internal German routes.[44][45]

Pan Am introduced the Douglas DC-7C "Seven Seas" on transatlantic routes in summer 1956. In January 1958 the DC-7C nonstop to London took 10 hours 45 minutes, enabling Pan Am to hold its own against TWA's Super Constellations and Starliners. In 1957 Pan Am started DC-7C flights direct from the US West Coast to London and Paris with a fuel stop in Canada or Greenland. The introduction of the faster Bristol Britannia turboprop by rival British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC) between New York and London from December 19, 1957 ended Pan Am's competitive leadership in that market.[46][42]

In January 1958 Pan Am scheduled 47 flights a week east from Idlewild to Europe, Africa, the Middle East and beyond.[40]

With growing competition on many of its routes, Pan Am began investing in innovations such as jet aircraft and widebody types.[47]

Pan Am was the launch customer of the Boeing 707, placing an order for 20 in October 1955. It also ordered 25 of Douglas's DC-8 for additional revenue-generating capacity due to its ability to seat six across (as opposed to five-abreast seating Boeing had originally offered on its 707). The combined order value was $269 million. To maintain its competitive lead as the first US aircraft manufacturer to offer a jetliner and meet its rival's competitive challenge, Boeing modified the 707's fuselage to seat six passengers across as well. The airline inaugurated transatlantic jet service from New York Idlewild to Paris Le Bourget[nb 3] on October 26, 1958, with Boeing 707-121 Clipper America (N711PA) carrying 111 passengers.[47][48]

Introduction of the 320 "Intercontinental" series 707 in 1959 enabled non-stop transatlantic jet crossings with a viable payload in both directions. These later-model 707s' increased capacity reduced seat-mile costs, helping Pan Am reinforce its transatlantic market dominance.[48]

Pan Am was also the launch customer of the Boeing 747, placing a $525 million order for 25 in April 1966.[49][50] On January 15, 1970, First Lady Pat Nixon officially christened a Pan Am Boeing 747 the Juan T. Trippe[51] at Washington Dulles in the presence of Pan Am president Najeeb Halaby. During the next few days, Pan Am flew several of their new 747s to various major airports in the US as part of a public relations effort, allowing the public to tour the airplanes. Pan Am then began its final preparations for the first commercial 747 service on the evening of January 21, 1970, when Clipper Young America was scheduled to fly from New York John F. Kennedy to London Heathrow. An engine failure delayed the inaugural flight's departure by several hours, necessitating the substitution of the originally scheduled aircraft with another 747, which eventually flew to London Heathrow.[52] Passengers cheered and drank champagne as the jet finally lifted off from the runway at John F. Kennedy Airport.

Pan Am was one of the first three airlines to sign options for the Concorde, but like other airlines that took out options — with the exception of BOAC and Air France — it did not purchase the supersonic jet. Pan Am was the first US airline to sign for the Boeing 2707, the American supersonic transport (SST) project, with 15 delivery positions reserved;[53] these aircraft never saw service after Congress voted against additional funding in 1971.[54]

Pan Am commissioned IBM to build PANAMAC, a large computer that booked airline and hotel reservations, which was installed in 1964. It also held large amounts of information about cities, countries, airports, aircraft, hotels, and restaurants.[55] The computer occupied the fourth floor of the Pan Am Building, which was the largest commercial office building in the world for some time.[56] The airline also built Worldport, a terminal building at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York. It was distinguished by its elliptical, four-acre (16,000 m²) roof, suspended far from the outside columns of the terminal below by 32 sets of steel posts and cables. The terminal was designed to allow passengers to board and disembark via stairs without getting wet by parking the nose of the aircraft under the overhang. The introduction of the jetbridge made this feature obsolete. Pan Am built a gilded training building in the style of Edward Durell Stone designed by Steward-Skinner Architects in Miami.[57]

At its peak in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Pan Am advertised under the slogan, the "World's Most Experienced Airline"[58]. It carried 6.7 million passengers in 1966, and by 1968, its 150 jets flew to 86 countries on every continent except for Antarctica over an unduplicated scheduled route network covering 81,410 miles (131,000 km). The number of scheduled destinations served peaked at 160. During that period, the airline was profitable and its cash reserves totaled $1 billion.[48] Most of its routes were between New York, Europe, and South America, and between Miami and the Caribbean. In 1964, Pan Am began providing a helicopter shuttle service between New York's three main airports[nb 4] and Lower Manhattan in association with New York Airways.[47] Aside from the DC-8, the Boeing 707 and 747, the Pan Am jet fleet also included Boeing 720Bs, 727s (the first aircraft to sport Pan Am — rather than Pan American — titles[48]), 737s, and Boeing 747SPs, which allowed Pan Am to fly nonstop New York to Tokyo. The airline also operated Lockheed L-1011 Tristars, McDonnell-Douglas DC-10s, and Airbus A300s and A310s. Pan Am also owned the InterContinental Hotel chain and had a financial interest the Falcon Jet Corporation, which held exclusive marketing rights to the Dassault Falcon 20 business jet in North America. The airline was furthermore involved in creating a missile-tracking range in the South Atlantic and operating a nuclear-engine testing laboratory in Nevada.[59] In addition, Pan Am participated in several notable humanitarian flights.[47]

From 1950 until 1990, Pan Am operated a comprehensive network of high-frequency, short-haul scheduled services between West Germany and West Berlin, first with Douglas DC-4s, then with DC-6Bs (from 1960) and Boeing 727s (from 1966).[44][45][60][61][62][63][64][65] (This had come about as a result of an agreement between the United States, the United Kingdom, France and the Soviet Union at the end of World War II, which prohibited Germany from having its own airlines and restricted the provision of commercial air services from and to Berlin to air transport providers headquartered in these four countries. Rising Cold War tensions between the Soviet Union and the three Western powers resulted in unilateral Soviet withdrawal from the quadripartite Allied Control Commission in 1948, culminating in the division of Germany the following year. These events, together with Soviet insistence on a very narrow interpretation of the post-war agreement on the Western powers' access rights to Berlin meant that until the end of the Cold War air transport in West Berlin continued to be confined to the carriers of the remaining Allied Control Commission powers, with aircraft required to fly across hostile East German territory through three 25-mile wide air corridors at a maximum altitude of 10,000 feet[nb 5].[66][48]) The airline's West Berlin operation consistently accounted for more than half of the city's entire commercial air traffic during that period.[67][68][69]

Pan Am operated Rest and Recreation (R&R) flights during the Vietnam War. These flights carried American service personnel for R&R leaves in Hong Kong, Tokyo, and other Asian cities.[70]

It is said that the airline was well regarded for its modern fleet[71] and experienced and professional crews: cabin staff were multilingual and usually college graduates, frequently with nursing training.[72] During this period, Pan Am's onboard service and cuisine, inspired by Maxim's de Paris, were delivered "with a personal flair that has rarely been equaled."[73][74]

Pan Am's London reservations number was REGent PAWA (7292).[75] Not many people were aware of this[citation needed], as London numbers were rarely quoted as letters other than the exchange name itself—unlike in New York.

Revenue passenger traffic (in millions of passenger-miles), scheduled flights only: 1,551 in 1951, 2,676 in 1955, 4,833 in 1960, 8,869 in 1965, 16,389 in 1970 and 14,863 in 1975.[76]

Downturn

Pan Am had invested in a large fleet of new Boeing 747s in the expectation that demand for air travel would continue to rise. This was not the case as the simultaneous introduction of a large number of these high-capacity aircraft by Pan Am and its principal competitors coincided with an economic slowdown. Reduced demand for air travel following the 1973 oil crisis made the airline industry's overcapacity problem worse, leaving Pan Am with its high overheads and fixed costs as a result of a large decentralized infrastructure in a vulnerable position. In addition, high jet fuel prices and the large number of older, less fuel-efficient narrowbodied airplanes in its fleet significantly increased the airline's operating costs. Federal route awards to other airlines, such as the Transpacific Route Case, further reduced the number of passengers Pan Am carried, as well as its profit margins.[9][50]

On September 23, 1974, a group of Pan Am employees published an advertisement in The New York Times to register their disagreement over federal policies which they felt were harming the financial viability of their employer.[77] The ad cited discrepancies in airport landing fees, such as Pan Am paying $4,200 to land a plane in Sydney, Australia, while the Australian carrier, Qantas, paid only $178 to land a jet in Los Angeles. The ad also contended that the United States Postal Service was paying foreign airlines five times as much to carry US mail in comparison to Pan Am. Finally, the ad questioned why the Export-Import Bank of the United States loaned money to Japan, France, and Saudi Arabia at 6% interest while Pan Am paid 12%.[78]

By the mid-1970s, Pan Am had racked up $364 million of accumulated losses[nb 6] and its debts approached $1 billion. This threatened the airline with bankruptcy. Former American Airlines vice president of operations, William T. Seawell, who had replaced Najeeb Halaby as Pan Am president in 1972, began implementing a turnaround strategy that entailed trimming the network by 25%, slashing the 40,000-strong workforce by 30% including wage cuts, introducing stringent economies and rescheduling debt, in addition to reducing the size of the fleet. These measures aided by the use of tax-loss credits enabled Pan Am to avert financial collapse and return to the black in 1977.[50]

Since the 1930s, Juan Trippe had coveted domestic routes for Pan Am. Throughout the late 1950s and early 1960s as well as in the mid-1970s the airline attempted to merge with American Airlines, Eastern Air Lines, and Trans World Airlines.[35] As rival airlines convinced Congress that Pan Am would use its political clout to monopolize all US air routes, the CAB repeatedly denied the airline permission to operate within the United States, either as a result of organic growth or a merger with another airline. As a consequence, Pan Am remained an American carrier operating international routes only (aside from Hawaii and Alaska). The last time Pan Am was permitted to merge with another airline prior to the deregulation of the airline industry in the United States was in 1950, when it took over American Overseas Airlines.[35] Following the US airline industry's deregulation in 1978, a growing number of US domestic operators began competing with Pan Am internationally.[79][80]

In order to acquire domestic routes, Pan Am, under president Seawell, set its eyes on National Airlines. Pan Am wound up in a bidding war with Frank Lorenzo, which greatly raised the price of National's stock. Nevertheless, Pan Am was granted permission to buy National in 1980 in what was described as the "Coup of the Decade." The acquisition of National Airlines for $437 million further burdened Pan Am's balance sheet, which was already under strain as a result of financing the large number of Boeing 747s that were ordered in the mid-1960s. This acquisition did little to improve Pan Am's competitive position in relation to nimbler, lower-cost competitors in a deregulated industry as National's North-South route structure provided insufficient feed at Pan Am's transatlantic and transpacific gateways in New York and Los Angeles respectively. In addition, both airlines had incompatible fleets (apart from the Boeing 727) and corporate cultures (partly as a result of the former being perceived by some Pan Am employees as mainly a regional "backwoods" carrier with few trunk routes), and the integration was poorly handled by Pan Am management who presided over an increase in labor costs as a result of harmonizing National's pay scales with Pan Am's.[81] Although revenues increased by 62% from 1979 to 1980, fuel costs from the merger increased by 157% during a weak economic climate. Further "miscellaneous expenses" increased by 74%.[82][83] As 1980 progressed and the airline's financial situation worsened, Seawell began selling Pan Am's non-core assets. The first asset to be sold off was the airline's 50% interest in Falcon Jet Corporation in August. Later in November, Pan Am sold the Pan Am Building to the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company for $400 million. In September 1981, Pan Am sold off its InterContinental hotels chain. Before this transaction closed, Seawell was replaced by C. Edward Acker, Air Florida's founder and ex-president as well as a former Braniff International executive. The combined sale value of the InterContinental chain and the Falcon Jet Corp stake was $500 million.[84][85]

Acker followed up the asset disposal program he had inherited from his predecessor with operational cutbacks. Most prominent among these was the discontinuation of the round-the world service from October 31 1982, when Pan Am ceased flying between Delhi, Bangkok and Hong Kong due to the sector's unprofitability.[86] To provide additional seating capacity for its 1983 spring/summer season, the airline also acquired three Boeing 747-200B passenger aircraft from Flying Tigers, who took four of Pan Am's 747-100 freighters in return.[87]

Despite Pan Am's precarious financial situation, during the summer of 1984, Acker went ahead with an order for new Airbus A300/A310/A320 wide- and narrowbodied aircraft. These technologically advanced aircraft, which were economically and operationally superior to the 747s and 727s Pan Am operated at the time, were intended to make the airline more competitive. Brand-new A300s began replacing aging 727s on the Internal German Services (IGS) and Caribbean networks later the same year while subsequently delivered new A310s replaced some of the 747s on the slimmed-down transatlantic network following ETOPS certification (approval by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) of transoceanic flying with twin-engined aircraft). Pan Am's decision not to take delivery of the A320s and to sell its delivery positions to Braniff meant that the majority of its short-haul US domestic and European mainline feeder routes, as well as most of its IGS services, continued to be flown with technologically obsolete 727s until the airline's demise. This put it at a commercial disadvantage against rivals operating state-of-the-art aircraft with a greater passenger appeal.[85] In September 1984, Pan American World Airways created a holding company called Pan Am Corporation to assume ownership and control of the airline and the services division.

Given the airline's dire state, in April 1985, Acker sold Pan Am's entire Pacific Division, which consisted of 25% of its entire route system, to United Airlines for $750 million. This sale also enabled Pan Am to address fleet incompatibility issues related to the earlier acquisition of National Airlines as it included Pan Am's Pratt & Whitney JT9D-powered 747SPs, its Rolls-Royce RB211-powered L-1011s and the General Electric CF6-powered DC-10s inherited from National, which were transferred to United along with the Pacific routes.[88][50]

The subsequent acquisition in June 1986 of Pennsylvania-based commuter airline Ransome Airlines for $65 million was meant to address the issue of providing additional feed for Pan Am's mainline services at its hubs in New York, Los Angeles and Miami in the United States, and Berlin in Germany.[89][90][88][85] The renamed Pan Am Express launched commuter routes from New York, Los Angeles and San Diego in the US, and Berlin, Germany. Miami services were added the following spring.[91] However, the regional Pan Am Express operation provided only an incremental feed to Pan Am's international route system, which was now focused on the Atlantic Division.

In an attempt to gain a presence on the busy Washington–New York–Boston commuter air corridor, the Ransome acquisition was accompanied by the $100 million purchase of New York Air's shuttle service between Boston, New York, and Washington, D.C. This parallel move was intended to enable Pan Am to provide a high-frequency service for high-yield business travelers in direct competition with the long-established, successful Eastern Air Lines shuttle operation. The renamed Pan Am Shuttle began operating out of LaGuardia Airport's refurbished historic Marine Air Terminal in October 1986. However, it did not address the pressing issue of Pan Am's continuing lack of a strong domestic feeder network.[85]

Thomas G. Plaskett, a former American Airlines and Continental executive, replaced Acker as president in January 1988 (joining Pan Am from the latter).[85] While a program to refurbish Pan Am aircraft and improve the company's on-time performance began showing positive results (in fact, Pan Am's most profitable quarter ever was third quarter of 1988), on December 21, 1988, the terrorist bombing of Pan Am flight 103 above Lockerbie, Scotland, resulted in 270 fatalities.[92] Pan Am's iconic image had made it a repeated target for terrorists, resulting in many travelers avoiding the airline as they had begun to associate it with danger. Faced with a $300 million lawsuit filed by more than 100 families of the Pan Am flight 103 victims, the airline subpoenaed records of six US government agencies, including the CIA, the Drug Enforcement Administration, and the State Department. Though the records suggested that the US government was aware of warnings of a bombing and failed to pass the information to the airline, the families claimed Pan Am was attempting to shift the blame.[93]

Also, in December 1988 the FAA fined Pan Am for 19 security failures, out of the 236 that were detected amongst 29 airlines.[94]

In June 1989 Plaskett presented Northwest Airlines with a $2.7 billion takeover bid that was backed by Bankers Trust, Morgan Guaranty Trust, Citicorp and Prudential-Bache. The proposed merger was Pan Am's final attempt to create a strong domestic network to provide sufficient feed for the two remaining mainline hubs at New York JFK and Miami. It was also intended to help the airline regain its status as a global airline by re-establishing a sizable transpacific presence. The merger was expected to result in annual savings of $240 million.[95][96] In the event, billionaire financier Al Checchi outbid Pan Am by presenting Northwest's directors with a superior proposal.

The first Gulf War triggered by the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait on August 2, 1990 sent fuel prices sky-rocketing, which severely depressed global economic activity. This in turn caused a sharp contraction of worldwide air travel demand, plunging hitherto profitable operations including Pan Am's prime transatlantic routes into steep losses. These unforeseen events constituted a further major blow to Pan Am, which was still reeling from the 1988 Lockerbie disaster. To shore up its finances, Pan Am sold most of its routes serving London Heathrow — arguably Pan Am's most important international destination — to United Airlines. This left Pan Am with only two daily London flights,[nb 7] which used Gatwick as their London terminal from the start of the 1990/91 winter timetable. Further asset disposals included Pan Am's sale of its IGS routes to Berlin to Lufthansa for $150 million, which became effective at the same time and brought the total value of asset disposals to $1.2 billion.[85][97] These measures were accompanied by the elimination of 2,500 jobs (8.6% of its work force). (This had already been announced by the airline in September 1990.)[98]

Bankruptcy

Pan Am was forced to declare bankruptcy on January 8, 1991. Delta Air Lines purchased the remaining profitable assets of Pan Am, including its remaining European routes[nb 8], the Shuttle operation, 45 jets and the Pan Am Worldport at John F. Kennedy Airport, for $416 million and injected $100 million as a 45% owner of a reorganized but smaller Pan Am serving the Caribbean, Central and South America from a main hub in Miami. The airline's creditors would hold the other 55%.[99][100][101][102][103][104]

The Boston-New York LaGuardia-Washington National Pan Am Shuttle service was taken over by Delta in September 1991.[105] Two months later Delta assumed all of Pan Am's remaining transatlantic traffic rights, except Miami to Paris and London.[100]

In October 1991 former Douglas Aircraft executive Russell Ray, Jr. was hired as Pan Am's new president and CEO.[106] As part of this restructuring, Pan Am relocated its headquarters from the Pan Am Building in New York City to new offices in the Miami area in preparation for the airline's relaunch from both Miami and New York on November 1, 1991.[107] The new airline would have operated approximately 60 aircraft and generate about $1.2 billion in annual revenues with 7,500 employees.[99] Following the relaunch, Pan Am continued to sustain heavy losses. Revenue throughout October and November 1991 fell short of what had been anticipated in the reorganization plan, with Delta claiming that Pan Am was losing $3 million a day. This undermined Delta's, Wall Street's and the traveling public's confidence in the viability of the reorganized Pan Am.[100][104]

Pan Am's senior executives outlined a projected shortfall of between $100 and possibly $200 million, with the airline requiring a $25 million installment just to fly through the following week.[citation needed] On the evening of December 3 Pan Am's Creditors Committee advised US Bankruptcy Judge Cornelius Blackshear that it was close to convincing an airline (TWA) to invest $15 million to keep Pan Am operating. A deal with TWA owner Carl Icahn could not be struck. Pan Am opened for business at 9:00 am and within the hour, Ray was forced to withdraw Pan Am's plan of reorganization and execute an immediate shutdown plan for Pan Am.[citation needed] Over 9,000 employees lost their jobs. As a result of this action, Delta was sued for more than $2.5 billion on December 9, 1991 by the Pan Am Creditors Committee.[108] Shortly thereafter, a large group of former Pan Am employees sued Delta.[104] In December 1995, a US federal judge ruled in favor of Delta, concluding that it was not liable for Pan Am's demise.[109]

Pan Am ceased operations on December 4, 1991, following a decision by Delta's CEO Ron Allen and other senior executives not to go ahead with the final $25 million payment Pan Am was scheduled to receive the weekend after Thanksgiving.[110][100] As a result, some 7,500 Pan Am employees lost their jobs, thousands of whom had worked in the New York City area and were preparing to move to the Miami area to work at Pan Am's new headquarters near Miami International Airport. Economists predicted that 9,000 jobs in the Miami area, including jobs at companies not connected to Pan Am that were dependent on the airline's presence, would be lost after it folded.[110] The carrier's last flown scheduled operation was Pan Am flight 436 which departed that day from Bridgetown, Barbados at 2 pm (EST) for Miami under the command of Captain Mark Pyle flying Clipper Goodwill, a Boeing 727–200 (N368PA).[111][100][104]

Pan Am was the third major airline to shut down in 1991, after Eastern Air Lines and Midway Airlines.[110]

After serving only two months as Pan Am's CEO, Ray was replaced by Peter McHugh to supervise the sale of Pan Am's remaining assets by Pan Am's Creditor's Committee.[citation needed] Pan Am's last remaining hub (at Miami International Airport) was split during the following years between United Airlines and American Airlines. TWA's Carl Icahn purchased Pan Am Express at a court ordered bankruptcy auction for $13 million and promptly renamed it Trans World Express.[citation needed] The Pan Am brand was sold to Charles Cobb, CEO of Cobb Partners and former United States Ambassador to the Republic of Iceland under President George H.W. Bush and Under Secretary of the US Department of Commerce under President Reagan. Cobb, along with Hanna-Frost partners invested in a new Pan American World Airways headed by veteran airline executive Martin R. Shugrue, Jr, a former Pan Am executive with 20 years of experience at the original carrier.[112]

In his book, Pan Am: An Aviation Legend, Barnaby Conrad III contends that the collapse of the original Pan Am was a combination of corporate mismanagement, government indifference to protecting its prime international carrier, and flawed regulatory policy.[113] He cites an observation made by former Pan Am Vice President for External Affairs, Stanley Gewirtz:

"What could go wrong did. No one who followed Juan Trippe had the foresight to do something strongly positive … it was the most astonishing example of Murphy's law in extremis. The sale of Pan Am's profitable parts was inevitable to the company's destruction. There were not enough pieces to build on".

— Stanley Gerwitz[114]

Under the terms of the airline bankruptcy, the airline's International Flight Academy in Miami, Florida was permitted to remain open. It was established as an independent training organization beginning in 1992 under its current name, Pan Am International Flight Academy. The company began operating by using the flight simulation and type rating training center of the defunct Pan Am. In 2006, American Capital Strategies invested $58 million into the academy.[115] Pan Am International Flight Academy is the only surviving division of Pan American World Airways.

Reuse of name

The Pan Am brand was resurrected four times after 1991, but the reincarnations were related to the original Pan Am in name only. In November 2010 Pan American Airways, Inc., was resurrected for a fifth time. The company's inaugural flight was to Monterrey, Mexico, on November 12, 2010.[116] The airline has said it will carry cargo only at this stage but intends to announce passenger service by 2011.[117]

Airlines

Pan American World Airways trademarks and some assets were purchased by Eclipse Holdings, Inc. at an auction by the US Bankruptcy Court on December 2-3, 1993. The scheduled airline rights were sold to Pan American Airways on December 20-29, 1993 by Eclipse Holdings, which was to retain the Pan Am charter rights and operate through its subsidiary Pan Am Charters, Inc., now Airways Corporation.

The first operated from 1996 to 1998, with a focus on low-cost, long-distance flights between the US and the Caribbean with the IATA airline designator PN.

The second was unrelated to the first and was a small regional carrier based in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, that operated between 1998 and 2004. It found its niche in operating usually at smaller airports near major airports, such as Pease International (Portsmouth), and Gary Municipal Airport, in Indiana. It used the IATA code PA, and the ICAO code PAA.

Boston-Maine Airways, a sister company of the second reincarnation, operated the "Pan Am Clipper Connection" brand from 2004 to February 2008. A domestic airline in the Dominican Republic, descended from the company's first reincarnation, continues to trade as Pan Am Dominicana. Pan American Airways and World-Wide Consolidated Logistics, Inc. will open cargo service to Latin America in 2011.

Railways

In 1998, Guilford Transportation Industries purchased Pan American World Airways and all related naming rights.[118] The railway is now operated as Pan Am Railways.

Record-setting flights

When Pearl Harbor was bombed a Boeing 314 was in New Zealand. With its Pacific bases attacked or abandoned, the seaplane was ordered to return via Australia, India, Arabia, Africa, South America and the Caribbean. It arrived in New York on January 6 after the first (almost) round-the-world airliner flight.[119]

During the mid-1970s Pan Am set two round-the-world records. Liberty Bell Express, a Boeing 747SP-21 named Clipper Liberty Bell, broke the commercial round-the-world record set by a Flying Tiger Line Boeing 707 with a new record of 46 hours, 50 seconds. The flight left New York-JFK on May 1, 1976 and returned on May 3. The flight stopped only in New Delhi and Tokyo, where a strike among the airport workers delayed it two hours. The flight beat the Flying Tiger Line's record by 16 hours 24 minutes.[120]

To commemorate its 50th birthday Pan Am organized a round-the-world flight San Francisco to San Francisco, this time over the North Pole and the South Pole with stops in London Heathrow, Cape Town and Auckland. 747SP-21 Clipper New Horizons was the former Liberty Bell, making the plane the only one to go around the globe over the Equator and the poles. The flight made it in 54 hours, 7 minutes, and 12 seconds, creating six new world records certified by the FAI. The captain who commanded the flight also commanded the Liberty Bell Express flight.[121]

Popular culture

Pan Am held a lofty position in the popular culture of the Cold War era. One of the most famous images in which a Pan Am plane formed a backdrop was The Beatles' 1964 arrival at John F. Kennedy Airport aboard a Pan Am Boeing 707-321, Clipper Defiance.[122]

From 1964 to 1968, con artist Frank Abagnale, Jr. masqueraded as a Pan Am pilot, dead-heading to many destinations in the cockpit jump seat. He also used Pan Am's preferred hotels, paid the bills with bogus checks, and later cashed fake payroll checks in Pan Am's name. He documented this era in the memoir Catch Me if You Can, which became a distantly related movie in 2002. Abagnale called Pan Am the "Ritz-Carlton of airlines" and noted that the days of luxury in airline travel are over.[123]

In the 1960s, Pan Am established a waiting list for future flights to the moon,[124] issuing free "First Moon Flights Club" membership cards to those who requested them. A fictional Pan Am "Space Clipper,"[124] a commercial spaceplane called the Orion III, had a prominent role in Stanley Kubrick's film 2001: A Space Odyssey and was featured in the movie's poster. Plastic models of the 2001 Pan Am Space Clipper were sold by both the Aurora Company and Airfix at the time of the film's release in 1968. A satire of the movie by Mad magazine in 1968 showed Pan Am female flight attendants in "Actionwear by Monsanto" outfits as they joked about the problems their passengers faced while vomiting in zero gravity. The film's sequel, 2010, also featured Pan Am in a background television commercial in the home of David Bowman's mother with the slogan, "At Pan Am, the sky is no longer the limit."[125]

The airline appeared in other movies, notably in several James Bond films. The company's Boeing 707s were featured in Dr. No and From Russia with Love, while a Pan Am 747 and the Worldport appeared in Live and Let Die.[126]

A term used in popular psychology is "Pan American (or Pan Am) Smile." Named after the greeting flight attendants (or at least actresses playing flight attendants on TV advertisements) supposedly gave to passengers. It consists of a perfunctory mouth movement without the activity of facial muscles around the eyes that characterizes a genuine smile.[127]

In 2011, ABC announced a new television series based on the lives of a 1960s Pan Am flight crew. The series, titled Pan Am, began airing in September 2011.[128]

Acquisitions and divestitures

- 1927: Pan American Airways, Atlantic, Gulf, and Caribbean Airways, and Aviation Corporation of the Americas founded.

- 1928: All three precursor firms merge into Aviation Corporation of the Americas, with Pan American Airways as its brand.

- 1929: Mexicana of Mexico acquired by Pan Am.

- 1929: Pan American-Grace Airways (PANAGRA), operating on the west coast of South America, formed as a 50–50 joint venture with W. R. Grace and Company.

- 1930: New York, Rio, and Buenos Aires Line (NYRBA) acquired, allowing Pan Am to operate along the east coast of South America. NYRBA's Brazilian subsidiary is renamed Panair do Brasil.

- 1931: Majority control of SCADTA of Columbia acquired in secret.

- 1932: Cubana of Cuba acquired.

- 1933: China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC) acquired.

- 1937: CNAC merged with China Airways.

- 1940: Minority holders of SCADTA bought-out.

- 1940: Aerovías of Guatemala formed.

- 1941: SCADTA merged into SACO to form Avianca, owned by the Colombian government.

- 1943: Aerovías Venezolanas Sociedad Anónima (AVENSA) of Venezuela founded as a joint venture.

- 1944: Cuban investors acquire 56% of Cubana through a stock float.

- 1946: InterContinental, a chain of hotels, founded.

- 1949: Pan Am acquires a stake in Middle East Airlines (MEA), as well as a management contract.

- 1949: Pan Am's 20% stake in CNAC acquired by Chinese Nationalists, with assets split variously between the Nationalists and the People's Republic of China.

- 1950: American Overseas Airlines (AOA) acquired from American Airlines.

- 1954: Cuban government acquires Pan Am's remaining stake in Cubana.

- 1955: Pan Am's 49% stake in MEA is sold to British Overseas Airways Corporation (BOAC).

- 1959: Mexican government acquires Pan Am's stake in Mexicana and Aeroméxico.

- 1961: Brazilian government acquires Panair do Brasil.

- 1967: PANAGRA sold to Braniff International Airways.

- 1976: AVENSA stake divested to Venezuelan government.

- 1980: National Airlines acquired.

- 1980: Pan Am Building sold to MetLife.

- 1981: InterContinental sold to Grand Metropolitan.

- 1986: Pacific Division sold to United Airlines.

- 1989: Pan Am unsuccessfully attempts to buy Northwest Airlines.

- 1990: London Heathrow routes sold to United Airlines.

- 1990: Internal German Services Division sold to Lufthansa.

- 1991: Atlantic Division, Pan Am Shuttle, and New York City Worldport sold to Delta Air Lines.

Accidents and incidents

Pan Am aircraft were involved in numerous accidents and incidents, including a number of Aircraft hijackings and terrorist attacks.[129]

An accident involving a Pan Am plane on December 8, 1963 led to the FAA's ordering the installation of safety devices on aircraft. The 707, named Clipper Tradewind (N709PA) and operating as flight 214, was in a holding pattern on a flight from Baltimore to Philadelphia when it was last seen going down in flames. It was determined that lightning had ignited vapors in the plane's fuel tanks. As a result of the disaster, lightning discharge wicks were installed on all commercial airliners.[130]

Between 1965 and 1974 a further five Pan Am 707s were involved in major accidents that resulted in substantial loss of lives. Three of these occurred on the airline's Pacific network between December 1973 and April 1974 within a time span of five months. More than 300 lives were lost in all five accidents, two-thirds of which were accounted for by the last three (30 fatalities: September 17, 1965 / 707-121B N708PA Montserrat, Caribbean; 51 fatalities: December 12, 1968 / 707-321B N494PA near Caracas, Venezuela; 78 fatalities: July 22, 1973 / 707-321B N417PA near Papeete Faaa; 97 fatalities: January 30, 1974 / 707-321B N454PA near Pago Pago, American Samoa; 107 fatalities: April 22, 1974 / 707-321B N446PA near Denpasar Ngurah Rai, Bali, Indonesia).[129]

A Pan Am 727 was also involved in an enduring Cold War mystery that remains unresolved to this day, which occurred on November 15, 1966. On that day, a company Boeing 727–21 (N317PA) operating the return leg of the airline's daily cargo flight from Berlin to Frankfurt Rhein-Main Airport (flight 708) was due to land that night at Tegel Airport, rather than Tempelhof, due to runway resurfacing work taking place at that time at the latter. Berlin Control had cleared flight 708 for an Instrument Landing System (ILS) approach to Tegel Airport's runway 08, soon after the crew had begun its descent from Flight Level (FL) 090 to FL 030 before entering the southwest air corridor over East Germany on the last stretch of its journey to Berlin. The aircraft impacted the ground near Dallgow, East Germany, almost immediately after the crew had acknowledged further instructions received from Berlin Control, just 10 mi (16 km) from Tegel Airport. All three crew members lost their lives in this accident. Visibility was poor, and it was snowing at the time of the accident. Following the accident, the Soviet military authorities in East Germany returned only half of the aircraft's wreckage to their US counterparts in West Berlin. This excluded vital parts, such as the flight data recorder (FDR), the cockpit voice recorder (CVR) as well as the plane's flight control systems, its navigation and communication equipment. The subsequent National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigation report concluded that the aircraft's descent below its altitude clearance limit was the accident's probable cause. However, the NTSB was unable to establish the factors that had caused the crew to descend below its cleared minimum altitude.[131][132][133]

On November 24, 1968 three hijackers demanding to go to Cuba took over a Pan Am Boeing 707 operating as flight 281 from New York to San Juan, Puerto Rico. The hijacking ended the same day with the release of the aircraft and its occupants.[134]

On August 3, 1970 a lone hijacker, who demanded to be flown to Hungary, took over a Pan Am Boeing 727-21 operating as flight 742 from Munich Riem Airport to Berlin Tempelhof Airport. The hijacking ended the same day with the release of the aircraft and its 125 occupants.[135]

On September 6, 1970 Pan Am flight 93, two men hijacked a Boeing 747-121 (N752PA) en route from Amsterdam to New York as part of the Dawson's Field hijackings. The flight diverted to Beirut International Airport to take on board seven other gang members for the next leg to Cairo. The hijackers instructed all 170 occupants to evacuate the aircraft immediately after landing at Cairo International Airport, following which they detonated explosives on board resulting in the plane's destruction.[136]

On December 17, 1973 five Palestinian terrorists, who had had taken six hostages at Rome Fiumicino Airport, bombed Pan Am flight 110 while passengers boarded. The Boeing 707-321B (Clipper Celestial, N407PA) caught fire, killing 30 people.[137]

On July 9, 1982 Clipper Defiance, a Boeing 727-235 (N4737), flying as Pan Am Flight 759, crashed minutes after takeoff from New Orleans International Airport in the worst accident in aviation history involving microburst-induced wind shear. All 145 passengers and crew members perished, as well as eight people on the ground when the plane careered through a residential area adjacent to the airport.[138]

On August 11, 1982, Pan Am flight 830, a Boeing 747-121 (N754PA), was bombed over the Pacific Ocean killing one passenger before safely landing in Honolulu.[139]

On September 5, 1986 a Pan Am 747 named the Clipper Empress of the Seas (N656PA), operating as Pan Am flight 73, was taken over by hijackers while on a scheduled stop in Karachi. The flight never departed Karachi, but 20 people were killed when the aircraft was stormed on the ground.[140]

On November 6, 1986 Eastern Air Lines Captain George Baines was flying in his private aircraft, a Piper PA-23 (N2185P), from his home to Tampa International to catch a flight. As he approached Tampa International's 36L (now 1L) in heavy fog, he declared a missed approach and went around to try it again. On the second attempt, he touched down on a parallel taxiway and ultimately collided with a Pan Am 727-200 that was taxiing on this taxiway. Baines lost his life in the accident. He was the only fatality. No other injuries were reported.[141][142]

Pan Am Flight 1736

Clipper Victor, which was the first Boeing 747 to operate carry fare-paying passengers in 1970 (N736PA), was involved in the Tenerife disaster on March 27, 1977, the deadliest air disaster in aviation history. On that day, Clipper Victor operated a charter flight, PA 1736, from Los Angeles to Las Palmas in the Canary Islands, Spain, via New York. The aircraft diverted to Los Rodeos Airport on Tenerife because of a bomb scare at Las Palmas. With visibility lessened by thick fog, a KLM 747 taking off in the mistaken belief they were cleared collided with the Pan Am airplane on the runway. A total of 583 people were killed. 335 passengers on the Pan Am plane died while 61 survived.[143]

Pan Am Flight 103

Pan Am Flight 103 was Pan Am's third daily scheduled transatlantic flight from London Heathrow Airport to New York John F. Kennedy Airport. On December 21, 1988 the aircraft flying this route, a Boeing 747-121, N739PAdisaster[144], named Clipper Maid of the Seas, was blown up as it flew over Lockerbie in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland, UK, when approximately 450 grams (0.99 lb)[145] of plastic explosive was detonated in its forward cargo hold, triggering a sequence of events that led to the rapid destruction of the aircraft. The aircraft that crashed was the 15th 747 ever built delivered to Pan Am in February 1970.[146] Until the September 11, 2001 attacks, the bombing of Pan Am Flight 103 was the second-deadliest terrorist attack against the United States and remains the largest terrorist attack on British soil to this day. A total of 270 people lost their lives, including 11 in the town of Lockerbie.[147]

Fleet

Fleet in 1990

The following were aircraft operated Pan Am and Pan Am Express in March 1990, a year and a half before the airline's collapse:

Pan Am Fleet, March 1990[148]

| Aircraft | In Service | Orders | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Airbus A300B4 | 12 | — | |

| Airbus A310-200 | 7 | — | |

| Airbus A310-300 | 12 | — | |

| Boeing 727-200 | 91 | 9 | Orders for used aircraft |

| Boeing 737-200 | 5 | — | |

| Boeing 747-100 | 18 | — | |

| Boeing 747-200B | 7 | — | |

| Total | 152 | 9 |

Pan Am Express Fleet, March 1990[148]

| Aircraft | In Service | Orders |

|---|---|---|

| ATR 42-300 | 8 | 3 |

| De Havilland Canada Dash 7 | 10 | — |

| Total | 18 | 3 |

Fleet History

All the aircraft ever operated by Pan Am:

| Aircraft | Years operated | Total | Type | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airbus A300-B4 | 1984-1991 | 13 | Jet aircraft | 2 more ordered |

| Airbus A310-224 | 1985-1991 | 7 | Jet aircraft | |

| Airbus A310-324 | 1987-1991 | 14 | Jet aircraft | |

| Airbus A320-200 | N/A | 0 | Jet aircraft | 50 ordered, never delivered to PA. First 16 delivered to Braniff (BN). |

| Avions de Transport Régional ATR-42 | ??-1991 | 12 | Turboprop aircraft | Operated by Pan Am Express |

| BAe Jetstream 31 | ??? | 10 | Turboprop aircraft | Operated by Pan Am Express |

| Boeing 307 Stratoliner | 1940-1948 | 3 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Boeing 314 | 1939-1946 | 9 | Flying boat | Carried first Transatlantic Air Mail |

| Boeing 377 Stratocruiser | 1949-1961 | 28 | Propeller aircraft | 8 Stratocruiser acquired from AOA |

| Boeing 707-121 | 1958-1974 | 8 | Jet aircraft | Launch customer of the 707 series |

| Boeing 707-321 | 1959-1973 | 26 | Jet aircraft | |

| Boeing 707-321B | 1962-1981 | 60 | Jet aircraft | |

| Boeing 707-321C | 1963-1979 | 34 | Jet aircraft | |

| Boeing 720B | 1963-1974 | 9 | Jet aircraft | |

| Boeing 727-121 | 1965-1991 | 46 | Jet aircraft | |

| Boeing 727-221 | 1979-1991 | 105 | Jet aircraft | |

| Boeing 737–200 | 1982-1991 | 16 | Jet aircraft | |

| Boeing 747-100 | 1969-1991 | 44 | Jet aircraft | Launch Customer of the Boeing 747-100 Series 33 Boeing 747–121s owned by Pan Am 5 Boeing 747–122s were bought from United Airlines 4 Boeing 747–123s were bought from American Airlines 2 Boeing 747–132s were bought from Delta Air Lines |

| Boeing 747-212B | 1974-1991 | 7 | Jet Aircraft | All 7 Boeing 747-212Bs were previously owned and operated by Singapore Airlines. |

| Boeing 747-273C | ??-1983 | 1 | Cargo Aircraft | Operated by Pan Am Cargo, was previously operated by World Airways. |

| Boeing 747-221F | ??-1983 | 2 | Cargo Aircraft | Operated by Pan Am Cargo |

| Boeing 747SP | 1976-1986 | 11 | Jet Aircraft | Launch Customer of the Boeing 747SP Series 10 Boeing 747SP-21s owned by Pan Am 1 Boeing 747SP-27 was bought by Braniff Airways |

| Consolidated Commodore | 1930-1943 | 14 | Flying boat | |

| Convair CV-240 | 1948-1957 | 20 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Convair CV-340 | 1953-1955 | 6 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Curtiss-Wright C-46 Commando | 1948-1956 | 12 | Propeller aircraft | |

| de Havilland Canada Dash 7 | ??-1991 | 8 | Turboprop aircraft | Operated by Pan Am Express |

| Douglas Dolphin | ??? | 2 | Flying boat | Transferred to CNAC |

| Douglas DC-2 | 1934-1941 | 9 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Douglas DC-3 | 1937-1948 | 90 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Douglas DC-4 | 1947-1961 | 22 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Douglas DC-6 | 1953-1968 | 49 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Douglas DC-7 | 1955-1966 | 37 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Douglas DC-8-32 | 1960-1970 | 19 | Jet aircraft | |

| Douglas DC-8-62 | 1970-1971 | 1 | Jet aircraft | DC-8-62 just operated one year |

| McDonnell-Douglas DC-10-10 | 1980-1984 | 11 | Jet aircraft | acquired from National in 1980 |

| McDonnell-Douglas DC-10-30 | 1980-1985 | 5 | Jet aircraft | acquired from National in 1980 |

| Fairchild FC-2 | 1928-1933 | 5 | Propeller aircraft | First aircraft of Pan Am's subsidiary Panagra |

| Fairchild 71 | 1930-1940 | 3 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Fairchild 91 | 1936-1937 | 2 | Propeller aircraft | 4 more ordered, but all cancelled |

| Fokker F-10A | 1929-1935 | 12 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Fokker F.VIIa/3m | 1927-1930 | 3 | Propeller aircraft | First Pan Am owned airplane to carry air mail |

| Ford Trimotor | 1929-1940 | 11 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Lockheed Model 9 Orion | 1935-1936 | 2 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Lockheed Model 10 Electra | 1934-1938 | 4 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Lockheed L-049 Constellation | 1946-1957 | 29 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Lockheed L-749 Constellation | 1947-1950 | 4 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Lockheed L-1049 Constellation | 1955 | 1 | Propeller aircraft | |

| Lockheed L-1011-500 TriStar | 1980-1986 | 12 | Jet aircraft | |

| Martin M-130 | 1935-1945 | 3 | Flying boat | Carried first Transpacific Air Mail |

| Sikorsky S-36 | ??? | 5 | Flying boat | |

| Sikorsky S-38 | 1928-1943 | 24 | Flying boat | |

| Sikorsky S-40 | 1931-1944 | 3 | Flying boat | First aircraft to carry the Clipper name |

| Sikorsky S-42 | 1934-1946 | 10 | Flying boat | |

| Sikorsky S-43 Baby Clipper | 1936-1945 | 10 | Flying boat |

See also

- Avensa

- Pan Am Air Bridge (Chalk's International Airlines sold its seaplane operations to a group of investors who operated Chalk's under the Bridge name with Pan Am logos)

- Pan American Airways (1996–1998)

- Pan American Airways (1998–2004)

- Boston-Maine Airways (operated Pan Am Clipper Connection from 2004 to February 2008)

- Pan Am Railways

- Pan Am Systems

- Pan Am destinations

- Pan Am (TV series)

- Pan Am International Flight Academy Only surviving division of Pan American World Airways

- Pan American Airways Guided Missile Range Division

Notes and Citations

- Notes

- ^ publicly held company with no or nominal assets other than money

- ^ The 1/46 Air Traffic Guide shows the B314 to Lisbon, but a B314 book says PA's last transatlantic B314 was in December 1945.

- ^ stopping in Gander

- ^ John F. Kennedy, LaGuardia and Newark

- ^ the cruising altitude of propliners employed on the Berlin Airlift

- ^ over a 10-year period

- ^ from Detroit and Miami

- ^ including the Frankfurt mini hub

- Citations

- ^ a b Guy Norris and Mark Wagner (September 1, 1997). "Birth of a Giant". Boeing 747: Design and Development Since 1969. Zenith Imprint. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0-7603-0280-4.

- ^ Airliner World (IATA: A new mandate in a changed world), p. 32, Key Publishing, Stamford, November 2011

- ^ Daley 1980, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Newton, Dr. Wesley P. (1967). "The Role of the Army Air Arm in Latin America, 1922–1931". Air Power Journal (September–October). Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ Anthony J. Mayo, Nitin Nohria and Mark Rennella, Entrepreneurs, Managers, and Leaders: What the Airline Industry Can Teach Us about Leadership (Macmillan, 2009) p49

- ^ a b c d e Siddiqi, As if (2003). "Air Transportation: Pan American: The History of America's "Chosen Instrument" for Overseas Air Transport". U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

- ^ John R. Steele, "The Very Beginning" History of Pan American World Airways: The Early Years

- ^ Bilstein 2001, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d "Chasing the Sun – Pan Am". PBS. 2001. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

- ^ Homan & Reilly 2000, p. 38.

- ^ "U.S. Aviation Development". Flight International. April 25, 1929. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

- ^ "50 years ago: 9 May 1956". Flight International. May 9, 2006. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

- ^ http://thescuttlefish.com/2010/09/pan-ams-seaplanes/ Pan Am's Seaplanes : The Scuttlefish

- ^ http://b377.ovi.ch/brochures/captain/index.html Meet Your Clipper Captain

- ^ http://www.clipperpioneers.com/NL09/CPNews509.pdf May 2009 - Clipper Pioneers Newsletter; Would You Believe? by Robert L. Bragg, Capt., Pan Am and United, Ret.

- ^ a b Masland, William M.,Through the Back Doors Of The World In A Ship That Had Wings, Vantage Press (1984)

- ^ http://runway.cloudaccess.net/points-of-departure/stories/78-recollections-of-dinner-key-.html Recollections of Dinner Key

- ^ Kauffman, Sanford; Hopkins, George (1995). Pan Am pioneer: a manager's memoir from seaplane clippers to jumbo jets. Texas Tech University Press. p. 195. ISBN 0896723577.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ a b Kauffman & Hopkins 1995, pp. 59, 195.

- ^ "China Clipper".

- ^ "Trans Pacific Airlines To Touch At Islands" Popular Mechanics, April 1935

- ^ "Wing Over The Pacific" Popular Mechanics, June 1935 see page 863

- ^ "Clipper Conquers Pacific on Hawaiian Hops" Popular Mechanics, July 1935

- ^ Wings Over The Pacific

- ^ Trautmann, James (2008). Pan American Clippers: The Golden Age of Flying Boats. The Boston Mills Press.

- ^ Pan American Airways System U.S. Cy. Passenger Tariff – Pacific, Orient, & Alaska Services Eff. May 1, 1937

- ^ LIFE, August 23, 1937

- ^ "Pan Am to Singapore". TIME. June 2, 1941.

- ^ Kauffman & Hopkins 1995, p. 212.

- ^ Gandt 1995, p. 19.

- ^ Greenfield, James (February 11, 1991). "Pan Am's Glory Days". The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- ^ http://flyingboatmuseum.com/coffee.php

- ^ Bilstein 2001, p. 173.

- ^ Lester, Valerie (1995). Fasten your seat belts!. Paladwr Press. pp. 86–89. ISBN 0962648388.

- ^ a b c d e f Aviation News (Pan American Airways: Part 2), p. 48, Key Publishing, Stamford, November 2011

- ^ airline timetable images, American Overseas Airlines - AOA

- ^ Bilstein 2001, p. 169.

- ^ a b Aviation News (Pan American Airways: Part 2 — South American problems), p. 50, Key Publishing, Stamford, November 2011

- ^ Pan Am global 747, Air Transport ..., Flight International, 28 October 1971, p. 677

- ^ a b c Pan American Airways System Timetable (pdf) January 1, 1958

- ^ "Pan American World Airways, Inc. Records – History". University of Miami Libraries, Special Collections. 2006. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- ^ a b c Aviation News (Pan American Airways: Part 2 — New name, new aircraft), p. 50, Key Publishing, Stamford, November 2011

- ^ Aviation News (The Douglas DC-4, DC-6 and DC-7), p. 64/5, Key Publishing, Stamford, November 2011

- ^ a b BEA in Berlin, Air Transport, Flight International, 10 August 1972, p. 180

- ^ a b Aeroplane — Pan Am and the IGS, Vol. 116, No. 2972, pp. 4, 8, Temple Press, London, 2 October 1968

- ^ "British Airways – History and heritage (Home > History & heritage > Explore our past >> 1950 - 1959 (1957: 19 December)". British Airways plc, London. 2011. Retrieved October 30, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Burns 2000.

- ^ a b c d e Aviation News (Pan American Airways: Part 2 — Leading the way), p. 50, Key Publishing, Stamford, November 2011

- ^ "Boeing 747–400 Program Milestones". Boeing.com. Retrieved August 27, 2005.

- ^ a b c d Aviation News (Pan American Airways: Part 2 — A falling star), p. 51, Key Publishing, Stamford, November 2011

- ^ Glionna, John M. (December 6, 2010). "Storied American Jetliner Languishes in Obscurity – in South Korea". Los Angeles Times.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ "Jumbo and the Gremlins". TIME. February 1, 1970. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- ^ Clausen, Meredith (2004). The Pan Am building and the shattering of the modernist dream. MIT Press. p. 357. ISBN 0262033240.

- ^ "Aerospace Industry. Refusal of Congress to approve Federal Funds for Development of Boeing Supersonic Airliner". Keesing's World News Archives. July 21, 1971. Retrieved June 1, 2009.

- ^ "Terminal Interchange from PANAMAC Airlines Reservation System". National Museum of American History. Retrieved September 12, 2010.

- ^ Horsley, Carter C. (2007). "The MetLife Building". The Midtown Book. Retrieved April 7, 2008. When it was completed, the 2,400,000 sq ft (220,000 m2) building became "the world's largest office building in bulk, a title it would lose a few years later to 55 Water Street downtown."

- ^ "Pan Am Training Facility (Miami 1963)". Beyond the Box Mid-Century Modern Architecture in Miami & New York. 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- ^ Conrad 1999, p. 164.

- ^ Ray 1999, p. 184.

- ^ Aeroplane — Tempelhof trials prelude to Pan Am 727 order, Vol. 108, No. 2773, p. 11, Temple Press, London, 10 December 1964

- ^ A Jet into Berlin Tempelhof, Air Commerce ..., Flight International, 17 December 1964, p. 1034

- ^ Aeroplane — The Battle of Berlin, Vol. 111, No. 2842, p. 15, Temple Press, London, 7 April 1966

- ^ Aeroplane — Commercial continued, Pan Am 727s take over in Berlin, Vol. 111, No. 2853, p. 11, Temple Press, London, 23 June 1966

- ^ Aeroplane — Pan Am and the IGS, Vol. 116, No. 2972, pp. 4, 5, 6, 8, Temple Press, London, 2 October 1968