PSMD7

26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 7, also known as 26S proteasome non-ATPase subunit Rpn8, is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the PSMD7 gene.[5][6]

The 26S proteasome is a multicatalytic proteinase complex with a highly ordered structure composed of 2 complexes, a 20S core and a 19S regulator. The 20S core is composed of 4 rings of 28 non-identical subunits; 2 rings are composed of 7 alpha subunits and 2 rings are composed of 7 beta subunits. The 19S regulator is composed of a base, which contains 6 ATPase subunits and 2 non-ATPase subunits, and a lid, which contains up to 10 non-ATPase subunits. Proteasomes are distributed throughout eukaryotic cells at a high concentration and cleave peptides in an ATP/ubiquitin-dependent process in a non-lysosomal pathway. An essential function of a modified proteasome, the immunoproteasome, is the processing of class I MHC peptides.

Gene

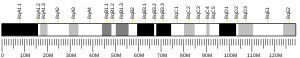

[edit]The gene PSMD7 encodes a non-ATPase subunit of the 19S regulator. A pseudogene has been identified on chromosome 17.[6] The human gene PSMD7 has 7 Exons and locates at chromosome band 16q22.3.

Protein

[edit]The human protein 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 14 is 37 kDa in size and composed of 324 amino acids. The calculated theoretical pI of this protein is 6.11.[7]

Complex assembly

[edit]26S proteasome complex is usually consisted of a 20S core particle (CP, or 20S proteasome) and one or two 19S regulatory particles (RP, or 19S proteasome) on either one side or both side of the barrel-shaped 20S. The CP and RPs pertain distinct structural characteristics and biological functions. In brief, 20S sub complex presents three types proteolytic activities, including caspase-like, trypsin-like, and chymotrypsin-like activities. These proteolytic active sites located in the inner side of a chamber formed by 4 stacked rings of 20S subunits, preventing random protein-enzyme encounter and uncontrolled protein degradation. The 19S regulatory particles can recognize ubiquitin-labeled protein as degradation substrate, unfold the protein to linear, open the gate of 20S core particle, and guide the substrate into the proteolytic chamber. To meet such functional complexity, 19S regulatory particle contains at least 18 constitutive subunits. These subunits can be categorized into two classes based on the ATP dependence of subunits, ATP-dependent subunits and ATP-independent subunits. According to the protein interaction and topological characteristics of this multisubunit complex, the 19S regulatory particle is composed of a base and a lid subcomplex. The base consists of a ring of six AAA ATPases (Subunit Rpt1-6, systematic nomenclature) and four non-ATPase subunits (Rpn1, Rpn2, Rpn10, and Rpn13).s The lid sub complex of 19S regulatory particle consisted of 9 subunits. The assembly of 19S lid is independent to the assembly process of 19S base. Two assembly modules, Rpn5-Rpn6-Rpn8-Rpn9-Rpn11 modules and Rpn3-Rpn7-SEM1 modules were identified during 19S lid assembly using yeast proteasome as a model complex.[8][9][10][11] The subunit Rpn12 incorporated into 19S regulatory particle when 19S lid and base bind together.[12] Recent evidence of crystal structures of proteasomes isolated from Saccharomyces cerevisiae suggests that the catalytically active subunit Rpn8 and subunit Rpn11 form heterodimer. The data also reveals the details of the Rpn11 active site and the mode of interaction with other subunits.[13]

Function

[edit]As the degradation machinery that is responsible for ~70% of intracellular proteolysis,[14] proteasome complex (26S proteasome) plays a critical roles in maintaining the homeostasis of cellular proteome. Accordingly, misfolded proteins and damaged protein need to be continuously removed to recycle amino acids for new synthesis; in parallel, some key regulatory proteins fulfill their biological functions via selective degradation; furthermore, proteins are digested into peptides for MHC class I antigen presentation. To meet such complicated demands in biological process via spatial and temporal proteolysis, protein substrates have to be recognized, recruited, and eventually hydrolyzed in a well controlled fashion. Thus, 19S regulatory particle pertains a series of important capabilities to address these functional challenges. To recognize protein as designated substrate, 19S complex has subunits that are capable to recognize proteins with a special degradative tag, the ubiquitinylation. It also have subunits that can bind with nucleotides (e.g., ATPs) in order to facilitate the association between 19S and 20S particles, as well as to cause confirmation changes of alpha subunit C-terminals that form the substrate entrance of 20S complex.

Clinical significance

[edit]The proteasome and its subunits are of clinical significance for at least two reasons: (1) a compromised complex assembly or a dysfunctional proteasome can be associated with the underlying pathophysiology of specific diseases, and (2) they can be exploited as drug targets for therapeutic interventions. More recently, more effort has been made to consider the proteasome for the development of novel diagnostic markers and strategies. An improved and comprehensive understanding of the pathophysiology of the proteasome should lead to clinical applications in the future.

The proteasomes form a pivotal component for the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) [15] and corresponding cellular Protein Quality Control (PQC). Protein ubiquitination and subsequent proteolysis and degradation by the proteasome are important mechanisms in the regulation of the cell cycle, cell growth and differentiation, gene transcription, signal transduction and apoptosis.[16] Subsequently, a compromised proteasome complex assembly and function lead to reduced proteolytic activities and the accumulation of damaged or misfolded protein species. Such protein accumulation may contribute to the pathogenesis and phenotypic characteristics in neurodegenerative diseases,[17][18] cardiovascular diseases,[19][20][21] inflammatory responses and autoimmune diseases,[22] and systemic DNA damage responses leading to malignancies.[23]

Several experimental and clinical studies have indicated that aberrations and deregulations of the UPS contribute to the pathogenesis of several neurodegenerative and myodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer's disease,[24] Parkinson's disease[25] and Pick's disease,[26] Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS),[26] Huntington's disease,[25] Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease,[27] and motor neuron diseases, polyglutamine (PolyQ) diseases, Muscular dystrophies[28] and several rare forms of neurodegenerative diseases associated with dementia.[29] As part of the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS), the proteasome maintains cardiac protein homeostasis and thus plays a significant role in cardiac ischemic injury,[30] ventricular hypertrophy[31] and heart failure.[32] Additionally, evidence is accumulating that the UPS plays an essential role in malignant transformation. UPS proteolysis plays a major role in responses of cancer cells to stimulatory signals that are critical for the development of cancer. Accordingly, gene expression by degradation of transcription factors, such as p53, c-jun, c-Fos, NF-κB, c-Myc, HIF-1α, MATα2, STAT3, sterol-regulated element-binding proteins and androgen receptors are all controlled by the UPS and thus involved in the development of various malignancies.[33] Moreover, the UPS regulates the degradation of tumor suppressor gene products such as adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) in colorectal cancer, retinoblastoma (Rb). and von Hippel–Lindau tumor suppressor (VHL), as well as a number of proto-oncogenes (Raf, Myc, Myb, Rel, Src, Mos, ABL). The UPS is also involved in the regulation of inflammatory responses. This activity is usually attributed to the role of proteasomes in the activation of NF-κB which further regulates the expression of pro inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-β, IL-8, adhesion molecules (ICAM-1, VCAM-1, P-selectin) and prostaglandins and nitric oxide (NO).[34] Additionally, the UPS also plays a role in inflammatory responses as regulators of leukocyte proliferation, mainly through proteolysis of cyclines and the degradation of CDK inhibitors.[35] Lastly, autoimmune disease patients with SLE, Sjögren syndrome and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) predominantly exhibit circulating proteasomes which can be applied as clinical biomarkers.[36]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000103035 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000039067 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Tsurumi C, DeMartino GN, Slaughter CA, Shimbara N, Tanaka K (May 1995). "cDNA cloning of p40, a regulatory subunit of the human 26S proteasome, and a homolog of the Mov-34 gene product". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 210 (2): 600–8. doi:10.1006/bbrc.1995.1701. PMID 7755639.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: PSMD7 proteasome (prosome, macropain) 26S subunit, non-ATPase, 7 (Mov34 homolog)".

- ^ "Uniprot: P51665 - PSMD7_HUMAN".

- ^ Le Tallec B, Barrault MB, Guérois R, Carré T, Peyroche A (Feb 2009). "Hsm3/S5b participates in the assembly pathway of the 19S regulatory particle of the proteasome". Molecular Cell. 33 (3): 389–99. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.010. PMID 19217412.

- ^ Gödderz D, Dohmen RJ (Feb 2009). "Hsm3/S5b joins the ranks of 26S proteasome assembly chaperones". Molecular Cell. 33 (4): 415–6. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.007. PMID 19250902.

- ^ Isono E, Nishihara K, Saeki Y, Yashiroda H, Kamata N, Ge L, Ueda T, Kikuchi Y, Tanaka K, Nakano A, Toh-e A (Feb 2007). "The assembly pathway of the 19S regulatory particle of the yeast 26S proteasome". Molecular Biology of the Cell. 18 (2): 569–80. doi:10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0635. PMC 1783769. PMID 17135287.

- ^ Fukunaga K, Kudo T, Toh-e A, Tanaka K, Saeki Y (Jun 2010). "Dissection of the assembly pathway of the proteasome lid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 396 (4): 1048–53. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.061. PMID 20471955.

- ^ Tomko RJ, Hochstrasser M (Dec 2011). "Incorporation of the Rpn12 subunit couples completion of proteasome regulatory particle lid assembly to lid-base joining". Molecular Cell. 44 (6): 907–17. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2011.11.020. PMC 3251515. PMID 22195964.

- ^ Pathare GR, Nagy I, Śledź P, Anderson DJ, Zhou HJ, Pardon E, Steyaert J, Förster F, Bracher A, Baumeister W (Feb 2014). "Crystal structure of the proteasomal deubiquitylation module Rpn8-Rpn11". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (8): 2984–9. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.2984P. doi:10.1073/pnas.1400546111. PMC 3939901. PMID 24516147.

- ^ Rock KL, Gramm C, Rothstein L, Clark K, Stein R, Dick L, Hwang D, Goldberg AL (Sep 1994). "Inhibitors of the proteasome block the degradation of most cell proteins and the generation of peptides presented on MHC class I molecules". Cell. 78 (5): 761–71. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(94)90462-6. PMID 8087844. S2CID 22262916.

- ^ Kleiger G, Mayor T (Jun 2014). "Perilous journey: a tour of the ubiquitin–proteasome system". Trends in Cell Biology. 24 (6): 352–9. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2013.12.003. PMC 4037451. PMID 24457024.

- ^ Goldberg, AL; Stein, R; Adams, J (August 1995). "New insights into proteasome function: from archaebacteria to drug development". Chemistry & Biology. 2 (8): 503–8. doi:10.1016/1074-5521(95)90182-5. PMID 9383453.

- ^ Sulistio YA, Heese K (Jan 2015). "The Ubiquitin–Proteasome System and Molecular Chaperone Deregulation in Alzheimer's Disease". Molecular Neurobiology. 53 (2): 905–31. doi:10.1007/s12035-014-9063-4. PMID 25561438. S2CID 14103185.

- ^ Ortega Z, Lucas JJ (2014). "Ubiquitin–proteasome system involvement in Huntington's disease". Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience. 7: 77. doi:10.3389/fnmol.2014.00077. PMC 4179678. PMID 25324717.

- ^ Sandri M, Robbins J (Jun 2014). "Proteotoxicity: an underappreciated pathology in cardiac disease". Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 71: 3–10. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.12.015. PMC 4011959. PMID 24380730.

- ^ Drews O, Taegtmeyer H (Dec 2014). "Targeting the ubiquitin-proteasome system in heart disease: the basis for new therapeutic strategies". Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 21 (17): 2322–43. doi:10.1089/ars.2013.5823. PMC 4241867. PMID 25133688.

- ^ Wang ZV, Hill JA (Feb 2015). "Protein quality control and metabolism: bidirectional control in the heart". Cell Metabolism. 21 (2): 215–26. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2015.01.016. PMC 4317573. PMID 25651176.

- ^ Karin, M; Delhase, M (2000). "The I kappa B kinase (IKK) and NF-kappa B: Key elements of proinflammatory signalling". Seminars in Immunology. 12 (1): 85–98. doi:10.1006/smim.2000.0210. PMID 10723801.

- ^ Ermolaeva MA, Dakhovnik A, Schumacher B (Jan 2015). "Quality control mechanisms in cellular and systemic DNA damage responses". Ageing Research Reviews. 23 (Pt A): 3–11. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2014.12.009. PMC 4886828. PMID 25560147.

- ^ Checler, F; da Costa, CA; Ancolio, K; Chevallier, N; Lopez-Perez, E; Marambaud, P (26 July 2000). "Role of the proteasome in Alzheimer's disease". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1502 (1): 133–8. doi:10.1016/s0925-4439(00)00039-9. PMID 10899438.

- ^ a b Chung, KK; Dawson, VL; Dawson, TM (November 2001). "The role of the ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway in Parkinson's disease and other neurodegenerative disorders". Trends in Neurosciences. 24 (11 Suppl): S7–14. doi:10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01998-6. PMID 11881748. S2CID 2211658.

- ^ a b Ikeda, K; Akiyama, H; Arai, T; Ueno, H; Tsuchiya, K; Kosaka, K (July 2002). "Morphometrical reappraisal of motor neuron system of Pick's disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with dementia". Acta Neuropathologica. 104 (1): 21–8. doi:10.1007/s00401-001-0513-5. PMID 12070660. S2CID 22396490.

- ^ Manaka, H; Kato, T; Kurita, K; Katagiri, T; Shikama, Y; Kujirai, K; Kawanami, T; Suzuki, Y; Nihei, K; Sasaki, H (11 May 1992). "Marked increase in cerebrospinal fluid ubiquitin in Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease". Neuroscience Letters. 139 (1): 47–9. doi:10.1016/0304-3940(92)90854-z. PMID 1328965. S2CID 28190967.

- ^ Mathews, KD; Moore, SA (January 2003). "Limb-girdle muscular dystrophy". Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports. 3 (1): 78–85. doi:10.1007/s11910-003-0042-9. PMID 12507416. S2CID 5780576.

- ^ Mayer, RJ (March 2003). "From neurodegeneration to neurohomeostasis: the role of ubiquitin". Drug News & Perspectives. 16 (2): 103–8. doi:10.1358/dnp.2003.16.2.829327. PMID 12792671.

- ^ Calise, J; Powell, S. R. (2013). "The ubiquitin proteasome system and myocardial ischemia". AJP: Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 304 (3): H337–49. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00604.2012. PMC 3774499. PMID 23220331.

- ^ Predmore, JM; Wang, P; Davis, F; Bartolone, S; Westfall, MV; Dyke, DB; Pagani, F; Powell, SR; Day, SM (2 March 2010). "Ubiquitin proteasome dysfunction in human hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies". Circulation. 121 (8): 997–1004. doi:10.1161/circulationaha.109.904557. PMC 2857348. PMID 20159828.

- ^ Powell, SR (July 2006). "The ubiquitin-proteasome system in cardiac physiology and pathology". American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 291 (1): H1–H19. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00062.2006. PMID 16501026. S2CID 7073263.

- ^ Adams, J (1 April 2003). "Potential for proteasome inhibition in the treatment of cancer". Drug Discovery Today. 8 (7): 307–15. doi:10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02647-3. PMID 12654543.

- ^ Karin, M; Delhase, M (February 2000). "The I kappa B kinase (IKK) and NF-kappa B: key elements of proinflammatory signalling". Seminars in Immunology. 12 (1): 85–98. doi:10.1006/smim.2000.0210. PMID 10723801.

- ^ Ben-Neriah, Y (January 2002). "Regulatory functions of ubiquitination in the immune system". Nature Immunology. 3 (1): 20–6. doi:10.1038/ni0102-20. PMID 11753406. S2CID 26973319.

- ^ Egerer, K; Kuckelkorn, U; Rudolph, PE; Rückert, JC; Dörner, T; Burmester, GR; Kloetzel, PM; Feist, E (October 2002). "Circulating proteasomes are markers of cell damage and immunologic activity in autoimmune diseases". The Journal of Rheumatology. 29 (10): 2045–52. PMID 12375310.

Further reading

[edit]- Coux O, Tanaka K, Goldberg AL (1996). "Structure and functions of the 20S and 26S proteasomes". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 65: 801–47. doi:10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.004101. PMID 8811196.

- Goff SP (Aug 2003). "Death by deamination: a novel host restriction system for HIV-1". Cell. 114 (3): 281–3. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00602-0. PMID 12914693. S2CID 16340355.

- Gridley T, Gray DA, Orr-Weaver T, Soriano P, Barton DE, Francke U, Jaenisch R (May 1990). "Molecular analysis of the Mov 34 mutation: transcript disrupted by proviral integration in mice is conserved in Drosophila". Development. 109 (1): 235–42. doi:10.1242/dev.109.1.235. PMID 2209467.

- Winkelmann DA, Kahan L (Apr 1983). "Immunochemical accessibility of ribosomal protein S4 in the 30 S ribosome. The interaction of S4 with S5 and S12". Journal of Molecular Biology. 165 (2): 357–74. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(83)80261-7. PMID 6188845.

- Seeger M, Ferrell K, Frank R, Dubiel W (Mar 1997). "HIV-1 tat inhibits the 20 S proteasome and its 11 S regulator-mediated activation". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (13): 8145–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.13.8145. PMID 9079628.

- Mahalingam S, Ayyavoo V, Patel M, Kieber-Emmons T, Kao GD, Muschel RJ, Weiner DB (Mar 1998). "HIV-1 Vpr interacts with a human 34-kDa mov34 homologue, a cellular factor linked to the G2/M phase transition of the mammalian cell cycle". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (7): 3419–24. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.3419M. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.7.3419. PMC 19851. PMID 9520381.

- Madani N, Kabat D (Dec 1998). "An endogenous inhibitor of human immunodeficiency virus in human lymphocytes is overcome by the viral Vif protein". Journal of Virology. 72 (12): 10251–5. doi:10.1128/JVI.72.12.10251-10255.1998. PMC 110608. PMID 9811770.

- Simon JH, Gaddis NC, Fouchier RA, Malim MH (Dec 1998). "Evidence for a newly discovered cellular anti-HIV-1 phenotype". Nature Medicine. 4 (12): 1397–400. doi:10.1038/3987. PMID 9846577. S2CID 25235070.

- Mulder LC, Muesing MA (Sep 2000). "Degradation of HIV-1 integrase by the N-end rule pathway". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (38): 29749–53. doi:10.1074/jbc.M004670200. PMID 10893419.

- Sheehy AM, Gaddis NC, Choi JD, Malim MH (Aug 2002). "Isolation of a human gene that inhibits HIV-1 infection and is suppressed by the viral Vif protein". Nature. 418 (6898): 646–50. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..646S. doi:10.1038/nature00939. PMID 12167863. S2CID 4403228.

- Ramanathan MP, Curley E, Su M, Chambers JA, Weiner DB (Dec 2002). "Carboxyl terminus of hVIP/mov34 is critical for HIV-1-Vpr interaction and glucocorticoid-mediated signaling". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 277 (49): 47854–60. doi:10.1074/jbc.M203905200. PMID 12237292.

- Thompson HG, Harris JW, Wold BJ, Quake SR, Brody JP (Oct 2002). "Identification and confirmation of a module of coexpressed genes". Genome Research. 12 (10): 1517–22. doi:10.1101/gr.418402. PMC 187523. PMID 12368243.

- Huang X, Seifert U, Salzmann U, Henklein P, Preissner R, Henke W, Sijts AJ, Kloetzel PM, Dubiel W (Nov 2002). "The RTP site shared by the HIV-1 Tat protein and the 11S regulator subunit alpha is crucial for their effects on proteasome function including antigen processing". Journal of Molecular Biology. 323 (4): 771–82. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00998-1. PMID 12419264.

- Gaddis NC, Chertova E, Sheehy AM, Henderson LE, Malim MH (May 2003). "Comprehensive investigation of the molecular defect in vif-deficient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions". Journal of Virology. 77 (10): 5810–20. doi:10.1128/JVI.77.10.5810-5820.2003. PMC 154025. PMID 12719574.

- Lecossier D, Bouchonnet F, Clavel F, Hance AJ (May 2003). "Hypermutation of HIV-1 DNA in the absence of the Vif protein". Science. 300 (5622): 1112. doi:10.1126/science.1083338. PMID 12750511. S2CID 20591673.

- Zhang H, Yang B, Pomerantz RJ, Zhang C, Arunachalam SC, Gao L (Jul 2003). "The cytidine deaminase CEM15 induces hypermutation in newly synthesized HIV-1 DNA". Nature. 424 (6944): 94–8. Bibcode:2003Natur.424...94Z. doi:10.1038/nature01707. PMC 1350966. PMID 12808465.

- Mangeat B, Turelli P, Caron G, Friedli M, Perrin L, Trono D (Jul 2003). "Broad antiretroviral defence by human APOBEC3G through lethal editing of nascent reverse transcripts". Nature. 424 (6944): 99–103. Bibcode:2003Natur.424...99M. doi:10.1038/nature01709. PMID 12808466. S2CID 4347374.