Medical gown

Medical gowns are hospital gowns worn by medical professionals as personal protective equipment (PPE) in order to provide a barrier between patient and professional. Whereas patient gowns are flimsy often with exposed backs and arms, PPE gowns, as seen below in the cardiac surgeon photograph, cover most of the exposed skin surfaces of the professional medics.

In several countries, PPE gowns for use in the COVID-19 pandemic became in appearance more like cleanroom suits as knowledge of the best practices filtered up through the national bureaucracies. For example, the European norm-setting bodies CEN and CENELEC on 30 March 2020 in collaboration with the European Commissioner for the Internal Market made freely-available the relevant standards documents in order "to tackle the severe shortage of protective masks, gloves and other products currently faced by many European countries. Providing free access to the standards will facilitate the work of the many companies wishing to reconvert their production lines in order to manufacture the equipment that is so urgently needed."[2]

History

[edit]The concept of PPE in regards to medical professionals was seen as early as the 17th century Plague doctor's outfit.

During the Ebola crisis of 2014, the WHO published a rapid advice guideline on PPE coveralls.[3]

Types

[edit]The different levels of various gown types are categorized as follows:[4]

| Level | Risk | Exposure | Product usable as/at | Protection levels | Tests |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One | Minimum | Standard isolation, Basic care | Visitor gown | Allows small amount of fluid penetration. Slight barrier to fluids. | Only one test of water impacting the gown material's surface is conducted to determine barrier protection. |

| Two | Low | Surgical suturing, and during blood draw | Pathology lab, Intensive care unit | Protection from fluids for longer period than level one gowns. | Two tests

|

| Three | Moderate | Intravenous therapy, and to draw arterial blood | In Trauma cases, or at Emergency | Protection from fluids for longer period than level two gowns. | Two tests

|

| Four | High | Surgery, and where pathogen transmission suspected | Operating theater | Protection against fluids and virus for one hour. | Three tests

|

Local variants

[edit]United States

[edit]In the United States, medical gowns are medical devices regulated by the Food and Drug Administration. FDA divides medical gowns into three categories. A surgical gown is intended to be worn by health care personnel during surgical procedures. Surgical isolation gowns are used when there is a medium to high risk of contamination and a need for larger critical zones of protection. Non-surgical gowns are worn in low or minimal risk situations.[5]

Surgical and surgical isolation gowns are regulated by the FDA as a Class II medical device that require a 510(k) premarket notification, but non-surgical gowns are Class I devices exempt from premarket review. Surgical gowns only require protection of the front of the body due to the controlled nature of surgical procedures, while surgical isolation gowns and non-surgical gowns require protection over nearly the entire gown.[5]

In 2004, the FDA recognized ANSI/AAMI PB70:2003 standard on protective apparel and drapes for use in health care facilities. Surgical gowns must also conform to the ASTM F2407 standard for tear resistance, seam strength, lint generation, evaporative resistance, and water vapor transmission. Because surgical gowns are considered to be a surface-contacting device with intact skin, FDA recommends that cytotoxicity, sensitization, and irritation or intracutaneous reactivity is evaluated.[5]

China

[edit]

The First Affiliated Hospital of the Zhejiang University School of Medicine in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, People's Republic of China developed their own protocol and equipment during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. A screenshot of the cover of the Handbook of COVID-19 Prevention and Treatment shows a picture of two rows of medical personnel, each wearing PPE gowns and PPE masks and PPE hoods and PPE goggles.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in Wuhan, doctors were provided with full PPE gown suits as early as January 2020.

European Union

[edit]During the COVID-19 pandemic, the European Commissioner for the Internal Market on 30 March 2020 listed the applicable norms for to help manufacturers re-convert their production lines:[2]

- Protective masks

- EN 149

- 2009-08: Respiratory protective devices – Filtering half masks to protect against particles - Requirements, testing, marking

- EN 14683

- 2019-10: Medical face masks - Requirements and test methods

- Eye protection

- EN 166

- 2002-04: Personal eye-protection – Specifications

- Protective clothing

- EN 14126

- 2004-01: Protective clothing - Performance requirements and tests methods for protective clothing against infective agents

- EN 14605

- 2009-08: Protective clothing against liquid chemicals - performance requirements for clothing with liquid-tight (Type 3) or spray-tight (Type 4) connections, including items providing protection to parts of the body only (Types PB [3] and PB [4])

- EN ISO 13688

- 2013-12 Protective clothing - General requirements (ISO 13688:2013)

- EN 13795-1

- 2019-06: Surgical clothing and drapes - Requirements and test methods – Part 1: Surgical drapes and gowns

- EN 13795-2

- 2019-06: Surgical clothing and drapes - Requirements and test methods – Part 2: Clean air suits

- Gloves

- EN 455-1

- 2001-01 Medical gloves for single use – Part 1: Requirements and testing for freedom from holes

- EN 455-2

- 2015-07: Medical gloves for single use – Part 2: Requirements and testing for physical properties

- EN 455-3

- 2015-07: Medical gloves for single use – Part 3: Requirements and testing for biological evaluation

- EN 455-4

- 2009-10: Medical gloves for single use – Part 4: Requirements and testing for shelf life determination

- EN 420

- 2010-03: Protective gloves - General requirements and test methods

- EN ISO 374-1

- 2018-10 Protective gloves against dangerous chemicals and micro-organisms – Part 1: Terminology and performance requirements for chemical risks

- EN ISO 374-5

- 2017-03: Protective gloves against dangerous chemicals and micro-organisms – Part 5: Terminology and performance requirements for micro-organisms risks (ISO 374-5:2016)

Israel

[edit]

As seen in the accompanying gallery figure, at least one Israeli hospital had access to full Tyvek PPE gowns as early as 17 March 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Italy

[edit]In an early April article, 20 doctors from the whole of Italy describe their experience with coronavirus patient care. Their conclusion reads:[6]

Instituting precise well-established plans to perform undeferrable surgical procedures and emergencies on COVID-19-positive patient is mandatory. Hospitals must prepare specific internal protocols and arrange adequate training of the involved personnel.

Their findings are set out in a table entitled "Necessary personal protection equipment":

- FFP2 facial mask or (in case of maneuvers at high risk of generating aerosolized particles:) FFP3 facial mask

- Disposable long sleeve waterproof coats, gowns, or Tyvek suits

- Disposable double pair of nitrile gloves

- Protective goggles or visors

- Disposable head caps

- Disposable long shoe covers

- Alcoholic hand hygiene solution

Criticisms

[edit]In a May 2017 research article, several French scientists complained that there was little harmonization across Europe for the names of pathogens, and went on to describe the PPE norms and regulations in France for infectious diseases under BSL-3.[7]

See also

[edit]- Plague doctor's outfit – Clothing worn by plague doctors that was intended to protect them from infection, historical equivalent

- Hazmat suit

- Workplace hazard controls for COVID-19

References

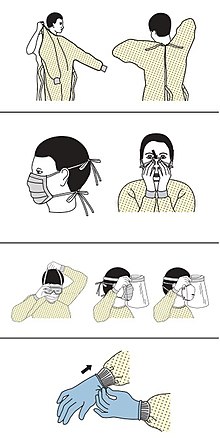

[edit]- ^ "Sequence for Putting On Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)" (PDF). CDC. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 March 2020. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ a b "COVID-19: DIN makes standards for medical equipment available". DIN Deutsches Institut für Normung e. V. 2020-03-30.

- ^ "Personal protective equipment for Ebola outbreak" (PDF). WHO. 31 October 2014.

- ^ Health, Center for Devices and Radiological (2021-01-13). "Medical Gowns". FDA.

- ^ a b c "Medical Gowns". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2020-03-11. Retrieved 2020-05-06.

- ^ Coccolini, F.; Perrone, G.; Chiarugi, M.; Di Marzo, F.; Ansaloni, L.; Scandroglio, I.; Marini, P.; Zago, M.; De Paolis, P.; Forfori, F.; Agresta, F.; Puzziello, A.; d'Ugo, D.; Bignami, E.; Bellini, V.; Vitali, P.; Petrini, F.; Pifferi, B.; Corradi, F.; Tarasconi, A.; Pattonieri, V.; Bonati, E.; Tritapepe, L.; Agnoletti, V.; Corbella, D.; Sartelli, M.; Catena, F. (2020). "Surgery in COVID-19 patients: Operational directives". World Journal of Emergency Surgery. 15 (1): 25. doi:10.1186/s13017-020-00307-2. PMC 7137852. PMID 32264898.

- ^ Pastorino, Boris; De Lamballerie, Xavier; Charrel, Rémi (2017). "Biosafety and Biosecurity in European Containment Level 3 Laboratories: Focus on French Recent Progress and Essential Requirements". Frontiers in Public Health. 5: 121. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2017.00121. PMC 5449436. PMID 28620600.