PPAR agonist

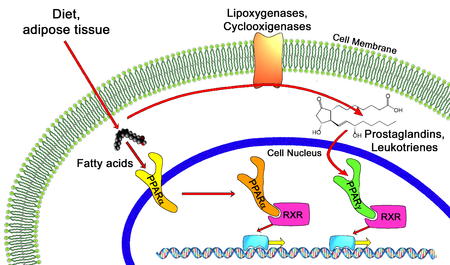

PPAR agonists are drugs which act upon the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor. They are used for the treatment of symptoms of the metabolic syndrome, mainly for lowering triglycerides and blood sugar.

Classification

[edit]PPAR-alpha and PPAR-gamma are the molecular targets of a number of marketed drugs. The main classes of PPAR agonists are:

PPAR-alpha agonists

[edit]An endogenous compound, 7(S)-Hydroxydocosahexaenoic Acid (7(S)-HDHA), which is a Docosanoid derivative of the omega-3 fatty acid DHA was isolated as an endogenous high affinity ligand for PPAR-alpha in the rat and mouse brain. The 7(S) enantiomer bound with micromolar affity to PPAR alpha with 10 fold higher affinity compared to the (R) enantiomer and could trigger dendritic activation.[1] PPARα (alpha) is the main target of fibrate drugs, a class of amphipathic carboxylic acids (clofibrate, gemfibrozil, ciprofibrate, bezafibrate, and fenofibrate). They were originally indicated for dyslipidemia of cholesterol and more recently for disorders characterized by high triglycerides.

PPAR-gamma agonists

[edit]PPARγ (gamma) is the main target of the drug class of thiazolidinediones (TZDs), used in diabetes mellitus and other diseases that feature insulin resistance. It is also mildly activated by certain NSAIDs (such as ibuprofen) and indoles, as well as from a number of natural compounds. Known inhibitors include the experimental agent GW-9662.

They are also used in treating hyperlipidaemia in atherosclerosis. Here they act by increasing the expression of ABCA1, which transports extra-hepatic cholesterol into HDL. Increased uptake and excretion from the liver therefore follows.

Animal studies have shown their possible role in amelioration of pulmonary inflammation, especially in asthma.[2]

PPAR-delta agonists

[edit]PPARδ (delta) is the main target of a research chemical named GW501516. It has been shown that agonism of PPARδ changes the body's fuel preference from glucose to lipids.[3]

Dual and pan PPAR agonists

[edit]A fourth class of dual PPAR agonists, so-called glitazars, which bind to both the α and γ PPAR isoforms, are currently under active investigation for treatment of a larger subset of the symptoms of the metabolic syndrome.[4][5] These include the experimental compounds aleglitazar, muraglitazar and tesaglitazar. In June 2013, saroglitazar was the first glitazar to be approved for clinical use.[6]

In addition, there is continuing research and development of new dual α/δ and γ/δ PPAR agonists for additional therapeutic indications, as well as "pan" agonists acting on all three isoforms.[7][8]

The anti-hypertension drug telmisartan is known to have PPAR γ/δ dual partial agonist activity in vivo. It also activates PPAR-α in vitro.[9]

Research

[edit]A relatively recent avenue of drug research in treating depression and drug addiction is through PPARα and PPARγ activation.[10] Both TLR4-mediated and NF-κB-mediated signalling pathways have been implicated in the development of addiction to several drugs such as opioids and cocaine, and therefore are appealing targets for pharmacotherapy.[11][12][13] Despite a breadth of preclinical research showing potential in animal models in the treatment of drug addictions including alcohol, nicotine, cocaine, opioids and methamphetamine, the human evidence is limited with the amount of trials looking at using PPAR agonists for humans still being low; and so far (as of 2020) not being particularly promising. There are several suggested hypotheses for the poor translation from animal to human research evidence such as the potency and selectivity of PPAR ligands, sex-related variability, and species differences in the distribution and signaling of PPAR.[14]

References

[edit]- ^ Jiabao Liu; et al. (2022). "The omega-3 hydroxy fatty acid 7(S)-HDHA is a high-affinity PPARα ligand that regulates brain neuronal morphology". Science Signaling. 15 (741): eabo1857. doi:10.1126/scisignal.abo1857. PMID 35857636.

- ^ Gu, M. X.; Liu, X. C.; Jiang, L (2013). "Effect of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma on proliferation of airway smooth muscle cells in mice with asthma". Zhongguo Dang Dai Er Ke Za Zhi = Chinese Journal of Contemporary Pediatrics. 15 (7): 583–7. doi:10.7499/j.issn.1008-8830.2013.07.018 (inactive 1 November 2024). PMID 23866284.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ B. Brunmair; et al. (2006). "Activation of PPAR-δ in isolated rat skeletal muscle switches fuel preference from glucose to fatty acids". Diabetologia. 49 (11): 2713–22. doi:10.1007/s00125-006-0357-6. PMID 16960684. S2CID 31757997.

- ^ Fiévet C, Fruchart JC, Staels B (2006). "PPARalpha and PPARgamma dual agonists for the treatment of type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 6 (6): 606–14. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2006.06.009. PMID 16973418.

- ^ Balakumar P, Rose M, Ganti SS, Krishan P, Singh M (2007). "PPAR dual agonists: are they opening Pandora's Box?". Pharmacol. Res. 56 (2): 91–8. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2007.03.002. PMID 17428674.

- ^ http://www.wallstreet-online.de/nachricht/6228479-zydus-gelingt-durchbruch-lipaglyn-wirkstoff-indien-markt-gelangt (in German)

- ^ Staels B, Fruchart JC (2005). "Therapeutic roles of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists". Diabetes. 54 (8): 2460–70. doi:10.2337/diabetes.54.8.2460. PMID 16046315.

- ^ Nevin DK, Fayne D, Lloyd DG (2011). "Rational targeting of peroxisome proliferating activated receptor subtypes". Current Medicinal Chemistry. 18 (36): 5598–623. doi:10.2174/092986711798347243. PMID 22172067.

- ^ Ayza, MA; Zewdie, KA; Tesfaye, BA; Gebrekirstos, ST; Berhe, DF (2020). "Anti-Diabetic Effect of Telmisartan Through its Partial PPARγ-Agonistic Activity". Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy. 13: 3627–3635. doi:10.2147/DMSO.S265399. PMC 7567533. PMID 33116714.

- ^ Le Foll B, Di Ciano P, Panlilio LV, Goldberg SR, Ciccocioppo R (2013). "Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) agonists as promising new medications for drug addiction: preclinical evidence". Current Drug Targets. 14 (7): 768–776. doi:10.2174/1389450111314070006. PMC 3826450. PMID 23614675.

- ^ Bachtell R, Hutchinson MR, Wang X, Rice KC, Maier SF, Watkins LR (2015). "Targeting the Toll of Drug Abuse: The Translational Potential of Toll-Like Receptor 4". CNS & Neurological Disorders Drug Targets. 14 (6): 692–9. doi:10.2174/1871527314666150529132503. PMC 5548122. PMID 26022268.

- ^ Nennig SE, Schank JR (2013). "The Role of NFkB in Drug Addiction: Beyond Inflammation". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 14 (7): 768–776. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agw098. PMC 6410896. PMID 28043969.

- ^ Russo SJ, Wilkinson MB, Mazei-Robison MS, Dietz DM, Maze I, Krishnan V, Renthal W, Graham A, Birnbaum SG, Green TA, Robison B, Lesselyong A, Perrotti LI, Bolaños CA, Kumar A, Clark MS, Neumaier JF, Neve RL, Bhakar AL, Barker PA, Nestler EJ (2009). "Nuclear Factor κB Signaling Regulates Neuronal Morphology and Cocaine Reward". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (11): 3529–3537. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.6173-08.2009. PMC 2677656. PMID 19295158.

- ^ Matheson, Justin; Le Foll, Bernard (May 2020). "Therapeutic Potential of Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (PPAR) Agonists in Substance Use Disorders: A Synthesis of Preclinical and Human Evidence". Cells. 9 (5): 1196. doi:10.3390/cells9051196. PMC 7291117. PMID 32408505.