BMI1

Polycomb complex protein BMI-1 also known as polycomb group RING finger protein 4 (PCGF4) or RING finger protein 51 (RNF51) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the BMI1 gene (B cell-specific Moloney murine leukemia virus integration site 1).[3][4] BMI1 is a polycomb ring finger oncogene.

Function

[edit]BMI1 (B lymphoma Mo-MLV insertion region 1 homolog) has been reported as an oncogene by regulating p16 and p19, which are cell cycle inhibitor genes. Bmi1 knockout in mice results in defects in hematopoiesis, skeletal patterning, neurological functions, and development of the cerebellum. Recently it has been reported that BMI1 is rapidly recruited to sites of DNA damage, where it sustains for over 8h. Loss of BMI1 leads to radiation sensitive and impaired repair of DNA double-strand breaks by homologous recombination.[5]

Bmi1 is necessary for efficient self-renewing cell divisions of adult hematopoietic stem cells as well as adult peripheral and central nervous system neural stem cells.[6][7] However, it is less important for the generation of differentiated progeny. Given that phenotypic changes in Bmi1 knockout mice are numerous and that Bmi1 has very broad tissue distribution, it is possible that it regulates the self-renewal of other types of somatic stem cells.[8]

Bmi1 is also thought to inhibit ageing in neurons through the suppression of p53.[9]

The Bmi-1 protein interacts with several signaling pathways containing Wnt, Akt, Notch, Hedgehog and receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK). In Ewing sarcoma family of tumors (ESFT), the knockdown of BMI-1 gene would greatly influence the Notch and Wnt signaling pathway which are important for ESFT formation and development.[10] Bmi-1 was shown to mediate the effect of Hedgehog signaling pathway on mammary stem cell proliferation.[11] Bmi-1 also regulates multiple downstream factors or genes. It represses p19Arf and p16Ink4a. Bmi-1-/- neural stem cells and HSCs have high expression level of p19Arf and p16Ink4a which diminished the proliferation rate.[12][13] Bmi-1 is also indicated as a key factor in controlling Th2 cell differentiation and development by stabilizing GATA transcription factors.[14]

Structure

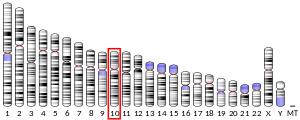

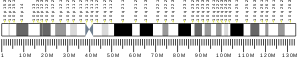

[edit]The BMI-1 gene is 10.04 kb with 10 exon and is highly conserved sequence between species. The human BMI-1 gene localizes at chromosome 10 (10p11.23). The Bmi-1 protein is consist of 326 amino acids and has a molecular weight of 36949 Da. Bmi1 has a RING finger at the N-terminus and a central helix-turn-helix domain.[15] The ring finger domain is a cysteine rich domain (CRD) involved in zinc binding and contributes to the ubiquitination process. The binding of bmi-1 to Ring 1B would activate the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity greatly. It is indicated that both the RING domain and the extended N-terminal tail contribute to the interaction of bmi-1 and Ring 1B.[16]

Clinical significance

[edit]Overexpression of Bmi1 seems to play an important role in several types of cancer, such as bladder, skin, prostate, breast, ovarian, colorectal as well as hematological malignancies. Its amplification and overexpression is especially pronounced in mantle cell lymphomas.[17] Inhibiting BMI1 has been shown to inhibit the proliferation of glioblastoma multiforme,[18] chemoresistant ovarian cancer, prostatic, pancreatic and skin cancers.[4] Colorectal cancer stem cell self-renewal was reduced by BMI1 inhibition. The colon cancer stem cells in mouse xenografts could be eliminated by inhibiting BMI-1 gene, providing a novel potential method to treat colorectal cancer.[19]

According to a study by Canadian doctors, the loss of the BMI1 gene expression in human neurons may play a direct role in the development of Alzheimer's disease.[20][21]

Interactions

[edit]BMI1 has been shown to interact with:

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000168283 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Alkema MJ, Wiegant J, Raap AK, Berns A, van Lohuizen M (October 1993). "Characterization and chromosomal localization of the human proto-oncogene BMI-1". Hum. Mol. Genet. 2 (10): 1597–603. doi:10.1093/hmg/2.10.1597. PMID 8268912.

- ^ a b Siddique HR, Saleem M (March 2012). "Role of BMI1, a stem cell factor, in cancer recurrence and chemoresistance: preclinical and clinical evidences". Stem Cells. 30 (3): 372–8. doi:10.1002/stem.1035. PMID 22252887. S2CID 7520976.

- ^ Fitieh A, Locke AJ, Mashayekhi F, Khaliqdina F, Sharma AK, Ismail IH (March 2022). "BMI-1 regulates DNA end resection and homologous recombination repair". Cell Reports. 38 (12): 110536–61. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110536. PMID 35320715. S2CID 247629517.

- ^ Lessard J, Sauvageau G (May 2003). "Bmi-1 determines the proliferative capacity of normal and leukaemic stem cells". Nature. 423 (6937): 255–60. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..255L. doi:10.1038/nature01572. PMID 12714970. S2CID 4426856.

- ^ Molofsky AV, He S, Bydon M, Morrison SJ, Pardal R (June 2005). "Bmi-1 promotes neural stem cell self-renewal and neural development but not mouse growth and survival by repressing the p16Ink4a and p19Arf senescence pathways". Genes Dev. 19 (12): 1432–7. doi:10.1101/gad.1299505. PMC 1151659. PMID 15964994.

- ^ Park IK, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF (January 2004). "Bmi1, stem cells, and senescence regulation". J. Clin. Invest. 113 (2): 175–9. doi:10.1172/JCI20800. PMC 311443. PMID 14722607.

- ^ Chatoo W, Abdouh M, David J, Champagne MP, Ferreira J, Rodier F, Bernier G (January 2009). "The polycomb group gene Bmi1 regulates antioxidant defenses in neurons by repressing p53 pro-oxidant activity". J. Neurosci. 29 (2): 529–42. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5303-08.2009. PMC 2744209. PMID 19144853.

- ^ Douglas D, Hsu JH, Hung L, Cooper A, Abdueva D, van Doorninck J, Peng G, Shimada H, Triche TJ, Lawlor ER (2008). "BMI-1 promotes ewing sarcoma tumorigenicity independent of CDKN2A repression". Cancer Res. 68 (16): 6507–15. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6152. PMC 2570201. PMID 18701473.

- ^ Liu S, Dontu G, Mantle ID, Patel S, Ahn NS, Jackson KW, Suri P, Wicha MS (2006). "Hedgehog signaling and Bmi-1 regulate self-renewal of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells". Cancer Res. 66 (12): 6063–71. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0054. PMC 4386278. PMID 16778178.

- ^ Molofsky AV, Pardal R, Iwashita T, Park IK, Clarke MF, Morrison SJ (2003). "Bmi-1 dependence distinguishes neural stem cell self-renewal from progenitor proliferation". Nature. 425 (6961): 962–7. Bibcode:2003Natur.425..962M. doi:10.1038/nature02060. PMC 2614897. PMID 14574365.

- ^ Park IK, Qian D, Kiel M, Becker MW, Pihalja M, Weissman IL, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF (2003). "Bmi-1 is required for maintenance of adult self-renewing haematopoietic stem cells". Nature. 423 (6937): 302–5. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..302P. doi:10.1038/nature01587. hdl:2027.42/62508. PMID 12714971. S2CID 4403711.

- ^ Hosokawa H, Kimura MY, Shinnakasu R, Suzuki A, Miki T, Koseki H, van Lohuizen M, Yamashita M, Nakayama T (2006). "Regulation of Th2 cell development by Polycomb group gene bmi-1 through the stabilization of GATA3". J. Immunol. 177 (11): 7656–64. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7656. PMID 17114435.

- ^ Itahana K, Zou Y, Itahana Y, Martinez JL, Beausejour C, Jacobs JJ, Van Lohuizen M, Band V, Campisi J, Dimri GP (January 2003). "Control of the Replicative Life Span of Human Fibroblasts by p16 and the Polycomb Protein Bmi-1". Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 (1): 389–401. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.1.389-401.2003. PMC 140680. PMID 12482990.

- ^ Li Z, Cao R, Wang M, Myers MP, Zhang Y, Xu RM (2006). "Structure of a Bmi-1-Ring1B polycomb group ubiquitin ligase complex". J. Biol. Chem. 281 (29): 20643–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M602461200. PMID 16714294.

- ^ Shakhova O, Leung C, Marino S (August 2005). "Bmi1 in development and tumorigenesis of the central nervous system" (PDF). Journal of Molecular Medicine. 83 (8): 596–600. doi:10.1007/s00109-005-0682-0. PMID 15976916. S2CID 24297688.

- ^ Abdouh M, Facchino S, Chatoo W, Balasingam V, Ferreira J, Bernier G (July 2009). "BMI1 sustains human glioblastoma multiforme stem cell renewal". The Journal of Neuroscience. 29 (28): 8884–96. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0968-09.2009. PMC 6665439. PMID 19605626.

- ^ Kreso A, van Galen P, Pedley NM, Lima-Fernandes E, Frelin C, Davis T, Cao L, Baiazitov R, Du W, Sydorenko N, Moon YC, Gibson L, Wang Y, Leung C, Iscove NN, Arrowsmith CH, Szentgyorgyi E, Gallinger S, Dick JE, O'Brien CA (January 2014). "Self-renewal as a therapeutic target in human colorectal cancer". Nature Medicine. 20 (1): 29–36. doi:10.1038/nm.3418. PMID 24292392. S2CID 13954804.

- ^ Eureka.net University of Montreal Understanding the origin of Alzheimer's, looking for a cure

- ^ Flamier, Anthony; El Hajjar, Jida; Adjaye, James; Fernandes, Karl J.; Abdouh, Mohamed; Bernier, Gilbert (May 2018). "Modeling Late-Onset Sporadic Alzheimer's Disease through BMI1 Deficiency". Cell Reports. 23 (9): 2653–2666. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2018.04.097. PMID 29847796.

- ^ a b Gunster MJ, Satijn DP, Hamer KM, den Blaauwen JL, de Bruijn D, Alkema MJ, van Lohuizen M, van Driel R, Otte AP (April 1997). "Identification and characterization of interactions between the vertebrate polycomb-group protein BMI1 and human homologs of polyhomeotic". Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 (4): 2326–35. doi:10.1128/mcb.17.4.2326. PMC 232081. PMID 9121482.

- ^ a b Satijn DP, Gunster MJ, van der Vlag J, Hamer KM, Schul W, Alkema MJ, Saurin AJ, Freemont PS, van Driel R, Otte AP (July 1997). "RING1 is associated with the polycomb group protein complex and acts as a transcriptional repressor". Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 (7): 4105–13. doi:10.1128/mcb.17.7.4105. PMC 232264. PMID 9199346.

- ^ Satijn DP, Otte AP (January 1999). "RING1 interacts with multiple Polycomb-group proteins and displays tumorigenic activity". Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 (1): 57–68. doi:10.1128/mcb.19.1.57. PMC 83865. PMID 9858531.

- ^ Barna M, Merghoub T, Costoya JA, Ruggero D, Branford M, Bergia A, Samori B, Pandolfi PP (October 2002). "Plzf mediates transcriptional repression of HoxD gene expression through chromatin remodeling". Dev. Cell. 3 (4): 499–510. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00289-7. PMID 12408802.

External links

[edit]- Human BMI1 genome location and BMI1 gene details page in the UCSC Genome Browser.

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P35226 (Polycomb complex protein BMI-1) at the PDBe-KB.

Further reading

[edit]- Ginjala V, Nacerddine K, Kulkarni A, Oza J, Hill SJ, Yao M, Citterio E, van Lohuizen M, Ganesan S (May 2011). "BMI1 is recruited to DNA breaks and contributes to DNA damage-induced H2A ubiquitination and repair". Mol. Cell. Biol. 31 (10): 1972–82. doi:10.1128/MCB.00981-10. PMC 3133356. PMID 21383063.

- Alkema MJ, van der Lugt NM, Bobeldijk RC, Berns A, van Lohuizen M (1995). "Transformation of axial skeleton due to overexpression of bmi-1 in transgenic mice". Nature. 374 (6524): 724–7. Bibcode:1995Natur.374..724A. doi:10.1038/374724a0. PMID 7715727. S2CID 4335040.

- Alkema MJ, Wiegant J, Raap AK, Berns A, van Lohuizen M (1994). "Characterization and chromosomal localization of the human proto-oncogene BMI-1". Hum. Mol. Genet. 2 (10): 1597–603. doi:10.1093/hmg/2.10.1597. PMID 8268912.

- Levy LS, Lobelle-Rich PA, Overbaugh J (1993). "flvi-2, a target of retroviral insertional mutagenesis in feline thymic lymphosarcomas, encodes bmi-1". Oncogene. 8 (7): 1833–8. PMID 8390036.

- Alkema MJ, Bronk M, Verhoeven E, Otte A, van 't Veer LJ, Berns A, van Lohuizen M (1997). "Identification of Bmi1-interacting proteins as constituents of a multimeric mammalian polycomb complex". Genes Dev. 11 (2): 226–40. doi:10.1101/gad.11.2.226. PMID 9009205.

- Gunster MJ, Satijn DP, Hamer KM, den Blaauwen JL, de Bruijn D, Alkema MJ, van Lohuizen M, van Driel R, Otte AP (1997). "Identification and characterization of interactions between the vertebrate polycomb-group protein BMI1 and human homologs of polyhomeotic". Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 (4): 2326–35. doi:10.1128/mcb.17.4.2326. PMC 232081. PMID 9121482.

- Satijn DP, Gunster MJ, van der Vlag J, Hamer KM, Schul W, Alkema MJ, Saurin AJ, Freemont PS, van Driel R, Otte AP (1997). "RING1 is associated with the polycomb group protein complex and acts as a transcriptional repressor". Mol. Cell. Biol. 17 (7): 4105–13. doi:10.1128/mcb.17.7.4105. PMC 232264. PMID 9199346.

- Alkema MJ, Jacobs J, Voncken JW, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Satijn DP, Otte AP, Berns A, van Lohuizen M (1997). "MPc2, a new murine homolog of the Drosophila polycomb protein is a member of the mouse polycomb transcriptional repressor complex". J. Mol. Biol. 273 (5): 993–1003. doi:10.1006/jmbi.1997.1372. PMID 9367786.

- Satijn DP, Otte AP (1999). "RING1 Interacts with Multiple Polycomb-Group Proteins and Displays Tumorigenic Activity". Mol. Cell. Biol. 19 (1): 57–68. doi:10.1128/mcb.19.1.57. PMC 83865. PMID 9858531.

- Voncken JW, Schweizer D, Aagaard L, Sattler L, Jantsch MF, van Lohuizen M (2000). "Chromatin-association of the Polycomb group protein BMI1 is cell cycle-regulated and correlates with its phosphorylation status". J. Cell Sci. 112 (24): 4627–39. doi:10.1242/jcs.112.24.4627. PMID 10574711.

- Bárdos JI, Saurin AJ, Tissot C, Duprez E, Freemont PS (2000). "HPC3 is a new human polycomb orthologue that interacts and associates with RING1 and Bmi1 and has transcriptional repression properties". J. Biol. Chem. 275 (37): 28785–92. doi:10.1074/jbc.M001835200. PMID 10825164.

- Trimarchi JM, Fairchild B, Wen J, Lees JA (2001). "The E2F6 transcription factor is a component of the mammalian Bmi1-containing polycomb complex". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (4): 1519–24. doi:10.1073/pnas.041597698. PMC 29289. PMID 11171983.

- Levine SS, Weiss A, Erdjument-Bromage H, Shao Z, Tempst P, Kingston RE (2002). "The Core of the Polycomb Repressive Complex Is Compositionally and Functionally Conserved in Flies and Humans". Mol. Cell. Biol. 22 (17): 6070–8. doi:10.1128/MCB.22.17.6070-6078.2002. PMC 134016. PMID 12167701.

- Suzuki M, Mizutani-Koseki Y, Fujimura Y, Miyagishima H, Kaneko T, Takada Y, Akasaka T, Tanzawa H, Takihara Y, Nakano M, Masumoto H, Vidal M, Isono K, Koseki H (2002). "Involvement of the Polycomb-group gene Ring1B in the specification of the anterior-posterior axis in mice". Development. 129 (18): 4171–83. doi:10.1242/dev.129.18.4171. PMID 12183370.

- Dimri GP, Martinez JL, Jacobs JJ, Keblusek P, Itahana K, Van Lohuizen M, Campisi J, Wazer DE, Band V (2002). "The Bmi-1 oncogene induces telomerase activity and immortalizes human mammary epithelial cells". Cancer Res. 62 (16): 4736–45. PMID 12183433.

- Barna M, Merghoub T, Costoya JA, Ruggero D, Branford M, Bergia A, Samori B, Pandolfi PP (2002). "Plzf mediates transcriptional repression of HoxD gene expression through chromatin remodeling". Dev. Cell. 3 (4): 499–510. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00289-7. PMID 12408802.

- Cmarko D, Verschure PJ, Otte AP, van Driel R, Fakan S (2003). "Polycomb group gene silencing proteins are concentrated in the perichromatin compartment of the mammalian nucleus". J. Cell Sci. 116 (Pt 2): 335–43. doi:10.1242/jcs.00225. PMID 12482919.

- Itahana K, Zou Y, Itahana Y, Martinez JL, Beausejour C, Jacobs JJ, Van Lohuizen M, Band V, Campisi J, Dimri GP (2003). "Control of the Replicative Life Span of Human Fibroblasts by p16 and the Polycomb Protein Bmi-1". Mol. Cell. Biol. 23 (1): 389–401. doi:10.1128/MCB.23.1.389-401.2003. PMC 140680. PMID 12482990.

- Park IK, Qian D, Kiel M, Becker MW, Pihalja M, Weissman IL, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF (2003). "Bmi-1 is required for maintenance of adult self-renewing haematopoietic stem cells". Nature. 423 (6937): 302–5. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..302P. doi:10.1038/nature01587. hdl:2027.42/62508. PMID 12714971. S2CID 4403711.

- Xia ZB, Anderson M, Diaz MO, Zeleznik-Le NJ (2003). "MLL repression domain interacts with histone deacetylases, the polycomb group proteins HPC2 and BMI-1, and the corepressor C-terminal-binding protein". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (14): 8342–7. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.8342X. doi:10.1073/pnas.1436338100. PMC 166231. PMID 12829790.