Arup Group

This article may have been created or edited in return for undisclosed payments, a violation of Wikipedia's terms of use. It may require cleanup to comply with Wikipedia's content policies, particularly neutral point of view. (October 2021) |

| Company type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Design, Engineering, Architecture and Business consultation |

| Founded | 1 April 1946 |

| Headquarters | , England |

Number of locations | 94 offices in 34 countries (2023) |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Jerome Frost (Chair) |

| Services | Consultancy services |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

Number of employees | |

| Subsidiaries | Ove Arup & Partners International Ltd, Arup Associates Ltd, and others. |

| Website | www |

Arup (officially Arup Group Limited) is a British multinational professional services firm headquartered in London that provides design, engineering, architecture, planning, and advisory services across every aspect of the built environment. It employs about 17,000 people in over 90 offices across 35 countries,[2] and has participated in projects in over 160 countries.[3][4]

Arup was established in 1946 by Sir Ove Arup as Ove N. Arup Consulting Engineers. Through its involvement in high-profile projects such as the Sydney Opera House, it became well known for undertaking complex and challenging projects.[5] In 1970, Arup stepped down from actively leading the company, setting out the principles which have continued to guide its operation.[5]

Arup's ownership is structured as a trust[6] whose beneficiaries are its employees, past and present, who receive a share of its operating profit each year.[7][8]

History

[edit]Founding the firm

[edit]The company was founded in London in 1946 as Ove N. Arup Consulting Engineers by Sir Ove Arup. Arup had established himself in the 1930s as an expert in reinforced concrete, known for projects such as the Penguin Pool at London Zoo.[9] According to the architectural author Ian Volner, Arup's vision when establishing the company came out of a combination of his wartime experiences and a progressive-minded philosophy broadly aligning with early modernism, was for the organisation to be a force for peace and social betterment in the postwar world.[5] To this end, it would employ professionals of diverse disciplines that could work together to produce projects of greater quality than was achievable by them working in isolation, a concept known as 'Total Design'.[5][10][11]

Early years

[edit]As the company grew, Arup spurned the common practice amongst its rivals of acquiring other companies; instead, it pursued natural growth, opening up new offices at locations where the potential for work had been identified.[5]

During 1963, together with the architect Philip Dowson, a new division of the company, Arup Associates, was formed.[12]

Within 25 years of its establishment, the firm had become well known for its design work for the built environment,[13][14] acquiring a reputation for its competence at undertaking projects that were structurally and/or logistically complex.[5] Arup himself worked on multiple projects during the firm's early years, including the Sydney Opera House, where he was lead engineer, and which author Peter Jones credited with launching Arup into the premier league of engineering consultancies.[15][16] The Opera House was the first application of computer calculations to an engineering project, using the Ferranti Pegasus computer to generate models.[17]

During Arup's lifetime, the company would also work on high-profile projects such as the 'inside-out' Centre Pompidou with Rogers & Piano, and the HSBC headquarters with Norman Foster & Partners.[18][19]

The Key Speech

[edit]1970 was a particularly transformative year for the firm; 24 years after founding the company, Arup opted to retire from actively leading the company. At the time, the firm (then Ove Arup & Partners) was made up of several independent practices spread across the globe, so prior to his departure, Arup delivered his 'Key Speech' on 9 July in Winchester to all his partners from the various practices.[20] The speech set out the aims of the firm and identified the principles of governance by which they might be achieved. These included quality of work, total architecture, humane organisation, straight and honorable dealings, social usefulness, and the reasonable prosperity of its members.[5]

Arup's philosophy work on influential projects was the subject of a dedicated retrospective at the V&A Museum in 2016.[21]

Operations

[edit]

Arup is an employee-owned business, with all staff owning a stake in the company and part of a global profit share.[22]

By 2013, Arup was operating 90 offices across 60 countries around the world.[5] These offices are elaborately interconnected by shared internet-based collaborative working packages and communication systems that can, where required, enable a single project to be worked on by multiple offices across a seamless, 24-hour working cycle. However, it is more common for individual offices to specialise in working on an assigned subsection of a project rather than continuously exchanging.[5]

The BBC Television and RIBA documentary The Brits who Built the Modern World highlighted Arup's collaboration with architects and described Arup as "the engineering firm which Lord Norman Foster and his peers Lord Richard Rogers, Sir Nicholas Grimshaw, Sir Michael Hopkins and Sir Terry Farrell most frequently relied upon."[23]

The firm has published an annual sustainability report since 2008, and is involved in several projects around the world aiming to cut greenhouse gas emissions,[24] such as Dongtan Eco-City, which is planned to be zero waste,[25] and the High Speed 2 Interchange Station, which is the first railway station in the world to achieve BREEAM 'outstanding certification.[26]

Arup also runs community engagement programmes comprising initiatives to combat homelessness,[27] improve sanitation in disaster relief programmes,[28] and disaster recovery after earthquakes.[29] They also engage in partnerships with governments, NGOs, think tanks, and other advocacy groups.[30][31]

Notable projects

[edit]

Africa

[edit]- Eastgate Centre, Harare, Zimbabwe (1996)

- Letsibogo Dam, Botswana (design and geotechnics, 1997)

- Constitutional Court, Johannesburg, South Africa (multidisciplinary engineers and project manager, 2004, architect: OMM)

- Scottish Livingstone Hospital, Molepolole, Botswana (design and construction supervision, 2007)

- Gautrain Rapid Rail Link Johannesburg to Pretoria, Sandton to OR Tambo International Airport, South Africa (concept studies and independent certification, 2010)

North America

[edit]- Apple Park is the corporate headquarters of Apple Inc, Cupertino, California, United States.

- Cathedral of Our Lady of the Angels, Los Angeles, US (mechanical and electrical engineers, 2002, architect: Rafael Moneo)

- De Young Museum, San Francisco, US (mechanical and electrical engineers, 2005, architects: Herzog & de Meuron)

- California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco, US (structural and services engineers, 2008, architect: Renzo Piano)

- New Tappan Zee Bridge (Hudson River), New York City (concept studies, 2009)

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Headquarters, Seattle, WA, US (structural and services engineers, 2011, architects: NBBJ)

- Fulton Center, New York City, US (structural engineers, 2014, HDR Daniel Frankfurt/Page Ayres Cowley Architects/Grimshaw Architects/Lee Harris Pomeroy Architects)

- High Roller, Las Vegas, NV, US (structural and electrical engineering, 2014, architects: The Hettema Group and Klai Juba Architects)[32]

- Gerald Desmond Bridge Design-Build Project, Long Beach, California (civil, structural, geotechnical design services, ongoing)

- Second Avenue Subway, New York City, US (tunnel engineering, ongoing)

- Lake Mead Intake No. 3, Nevada, US (tunnel engineering)

- Champlain Bridge, Montreal, Qc, Canada (bridge design)

- Little Island, New York, New York City, US

Asia

[edit]

- Druk White Lotus School was built to survive the Ladakhi weather.

- Kingdom Centre, The third tallest skyscraper in Saudi Arabia, and the second tallest in Riyadh and an icon of it.

- Aspire Tower, one of the tallest buildings in Qatar.

- HSBC Building (Hong Kong) (civil and structural engineers, 1985, architects: Foster + Partners)

- Kansai International Airport, Osaka, Japan (structural and services engineers, 1994, architect: Renzo Piano)

- Vattanac Capital Phnom Penh, Cambodia (structural engineers, 2014, architect: Farrells)

- Petron Megaplaza, Makati, Philippines (structural engineers, 1998, architect: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill)

- International Finance Centre, Hong Kong (structural and geotechnical engineers, 2003, Rocco Design Architects)

- National Aquatics Centre (Water Cube), Beijing, China (design and structural engineers, 2008, architects: PTW Architects/CSCEC/CCDI)

- Beijing National Stadium (the "Bird's Nest"), Beijing, China (structural engineers, 2008, architects: Herzog & de Meuron/China Architectural Design & Research Group/Ai Weiwei)

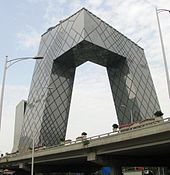

- CCTV Headquarters, Beijing, China (structural engineers, 2008, architects: Rem Koolhaas and Ole Scheeren/OMA)

- Fusionopolis, Singapore (structural and specialist engineers, 2008, architects: Kisho Kurokawa)

- Rajiv Gandhi International Airport, Delhi, India (full engineering services, 2008, architect: Integrated Design Associates)

- Singapore Flyer, Singapore (structural engineers, 2008, architects: Kisho Kurokawa/DP)

- Stonecutters Bridge, Hong Kong (bridge engineers, 2009, architect: Dissing+Weitling)

- Dongtan, Shanghai, China (design and masterplan, 2010, main designer: Thomas V. Harwood III)

- Canton Tower, Guangzhou, China (structural engineers, 2010, architects: Mark Hemel/Barbara Kuit/IBA)

- King Power MahaNakhon, Bangkok, Thailand (structural engineers 2016, architects: Ole Scheeren)

- Marina Bay Sands Integrated Resort, Singapore (structural and specialist engineers, 2010, architects: Moshe Safdie/Aedas)

- The Helix, Singapore (structural, civil, maritime, mechanical, electrical engineers, lighting designers 2010, architects: Cox Architects/architects61)

- Singapore Sports Hub, Singapore (structural and specialist engineers, 2010, architects: Arup Associates (Arup Sport)/DP Architects)

- King Abdullah Sports City (The Jewel), Jeddah, Saudi Arabia (structural and services engineers, 2014, architect: Arup Associates (Arup Sport))

- Capitol Development, Singapore (structural, civil, mechanical, electrical, facade, fire engineers, sustainability and vertical transportation consultants 2015, architects: Richard Meier & Partners/architects61)

- Tanjong Pagar Centre, Singapore (structural and facade engineers, sustainability consultants 2016, architects: Skidmore, Owings & Merrill)

- Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport, Taiwan Taoyuan International Airport, Terminal 3, Taiwan (expected to be opened in 2020)

- Aldar Headquarters building, Abu Dhabi, rounded skyscraper (2009)

- King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center, a non-profit institution for independent research into global energy economics located in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.[33]

Australia

[edit]

- Sydney Opera House, Sydney (structural engineers, 1973, architect: Jørn Utzon)

- Melbourne Museum, Melbourne (civil and structural engineers, 2000, architects: Denton Corker Marshall)

- Swan Bells, Perth, (structural engineers, 2000, architects: Hames Sharley)

- Goodwill Bridge, Brisbane, (bridge design, 2001, architects: Cox Rayner)

- National Museum of Australia, Canberra, (structural engineers, 2001, architects: Howard Raggatt)

- Lang Park redevelopment, Brisbane, (masterplanning, civil and structural engineers, 2003, architects: Populous/PDT)

- National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, (structural engineers, 2003, architects: Mario Bellini)

- State Library of Victoria, Melbourne, (structural engineers, 2004, architects: Ancher Mortlock & Woolley)

- Melbourne Cricket Ground, Melbourne, (civil and structural engineers, 2005, architects: MCG5)

- Australian Synchrotron, Melbourne, (specialist engineering, 2007)

- Kurilpa Bridge, Brisbane (bridge design, 2009, architects: Cox Rayner)

- Melbourne Recital Centre & Melbourne Theatre Company Theatre, Melbourne, (acoustic and theatre engineers, 2009, architects: Ashton Raggat McDougall)

- Andrew "Boy" Charlton Pool, Sydney, (structural and services engineering, 2011, architects: Lippmann Associates)

- Melbourne Star, Melbourne, (structural engineering, 2013)

- Perth Stadium, Perth, (civil and structural engineering, 2017, architects: Hassell, HKS, Cox)

Europe

[edit]

- Light House, London, UK (environmental and structural engineering)

- Coventry Cathedral, UK (structural engineers, 1962, architect: Sir Basil Spence)

- Kingsgate Bridge, Durham, UK (engineering design, 1966)

- Preston bus station, Lancashire, UK (structural engineering, 1969)

- Greyfriars bus station, Northampton, UK (engineering design, 1976)

- Pompidou Centre, Paris, France (structural and service engineers, 1977, architects: Renzo Piano & Richard Rogers)

- The Barbican Centre, London, UK (civil and structural engineers, 1982, architects: Chamberlin, Powell and Bon)

- Lloyds Building, London, UK (building engineers and project planners, 1986, architect: Richard Rogers)

- Angel of the North, Gateshead, UK (advanced structural research, 1998, designer: Antony Gormley)

- London Eye, London, UK (structural engineers, 2000, architect: Marks Barfield)[34]

- Millennium Bridge, London, UK (bridge engineering, 2000, architects: Foster + Partners and Sir Anthony Caro)

- Øresund Bridge, Denmark / Sweden (planning and bridge engineering, 2000, architects: Dissing+Weitling)

- Sony Center, Berlin, Germany (structural and environmental engineers, 2000, architect: Helmut Jahn)

- HSBC Tower, London, UK (structural engineers, 2002, architects: Foster + Partners)

- City of Manchester Stadium, Manchester, England, UK (Arup Associates architects, 2002)

- Selfridges, Birmingham, UK (structural engineers, 2003, architect: Future Systems)

- 30 St Mary Axe ("The Gherkin"), London, UK (structural engineers, 2004, architect: Foster + Parners)

- Scottish Parliament Building, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK (structural, civil, façade, geotechnical, blast and landscaping engineers, 2004, architect: Enric Miralles)

- Allianz Arena, Munich, Germany (structural engineers, 2005, architects: Herzog & de Meuron)

- Arnolfini refurbishment, Bristol, England, UK (structural, mechanical and electrical engineers, 2005, architects: Snell Associates)

- Casa da Música, Porto, Portugal (building engineers, 2005: architects: Rem Koolhaas/OMA)

- Restoration programme of Brunel's SS Great Britain, Bristol, England, UK (civil and structural engineers, 2005, architect: Alex French Partnership)

- Kanyon Shopping Mall, Istanbul, Turkey (structural engineers, 2006, architect: Tabanlıoğlu Architects)

- Nescio Bridge, Amsterdam, Netherlands (structural engineers, 2006, architect: Wilkinson Eyre)

- High Speed 1, UK (rail engineering, 2007)

- Terminal 5 at Heathrow Airport, England, UK (civil engineers, 2008, architect: Richard Rogers)

- Ahmed Adnan Saygun Arts Center, İzmir, Turkey (acoustic consulting, 2008, architect: Tozkoparan Architecture)[35]

- Snowdon Summit Building, Wales, UK (structural engineers, 2009, Ray Hole Architects)

- Donbass Arena, Ukraine (structural engineers, 2009)

- Grand Canal Theatre, Dublin, Ireland (acoustic, theatre technical, structural and building services engineers, 2010, architect: Daniel Libeskind)

- London Aquatics Centre, London, UK (structural and services engineers, 2012, architect: Zaha Hadid)

- The Shard, London, UK (services engineers, 2013, architect: Renzo Piano)

- Sky Studios, London, UK (Arup Associates architects, 2013)

- Nou Mestalla Stadium, Valencia, Spain (structural engineers, ongoing, architects: Reid Fenwick Asociados)

- Seat of the European Central Bank, Frankfurt, Germany (building services engineers, ongoing, architect: Coop Himmelb(l)au)

- Lakhta Center, Saint Peterburg, Russia (verification calculation for the underground part, foundation pile base and the superstructure, ongoing, architect: Tony Kettle, RMJM)

Sports

[edit]Arup had its own sports division, specialising in designing, consulting and structural engineering for sporting facilities such as stadia.[36] Many of Arup's modern stadia are designed with a contemporary, distinctive edge and the company strives to revolutionise stadium architecture and performance.[36] For instance, the Bird's Nest Stadium for the 2008 Olympics was complimented for its striking architectural appearance[37] and the City of Manchester Stadium for the 2002 Commonwealth Games has stairless entry to the upper tiers through circular ramps outside the stadium.[36] The most notable stadium projects led by Arup remain the City of Manchester Stadium (2002), Allianz Arena (2005), Beijing National Stadium (2008), Donbass Arena (2009) and the Singapore Sports Hub (2014).

-

The City of Manchester Stadium built for 2002 Commonwealth Games and now home of Manchester City F.C.

-

Allianz Arena in Germany, home of FC Bayern Munich

-

The 'Bird's Nest or Beijing National Stadium, for 2008 Summer Olympics, Beijing and national stadium of China

Awards

[edit]Awards to group

[edit]The firm is consistently placed amongst top performers in Corporate and Social Responsibility rankings such as the ACCSR.[38]

Arup's multidisciplinary sports venue design and engineering scope on the Singapore Sports Hub won the 2013 World Architecture Festival Award in the Future Projects, Leisure Category.[39]

The Casa da Música, Oporto, designed by Arup and Office for Metropolitan Architecture was nominated for the 2007 Stirling Prize.[40]

Arup's work with The Druk White Lotus School, Ladakh, won them Large Consultancy Firm of the Year 2003 at the British Consultants and Construction Bureau – International Expertise Awards, 2003 building on their triple win at the 2002 World Architecture Awards.[41]

Arup was awarded the Worldaware Award for Innovation for its Vawtex air system in Harare International School.[42]

Arup won the Gold Medal for Architecture at the National Eisteddfod of Wales of 1998 for their work on the Control Techniques Research and Development HQ, in Newtown, Powys.[43]

Arup Fire has won the Fire Safety Engineering Design award four times since its creation in 2001.[44] The 2001 inaugural award was won for Arup's contribution to the Eden Project in Cornwall, UK, the world's largest greenhouse. In 2004, the design for London's City Hall was appointed joint winner. In 2005, the Temple Mills Eurostar Depot won. The 2006 winning entry was for Amethyst House, a nine-storey building with an atrium from the ground to the top, in Manchester, UK.[45]

Arup was Royal Town Planning Institute Consultancy of the year in 2008.[46]

Arup was awarded the 2010 Live Design Excellence Award for Theatre Design for the integrated theatre and acoustic team's design for the new Jerome Robbins Theatre, created for Mikhail Baryshnikov and The Wooster Group.[47]

The Evelyn Grace Academy, London designed by Zaha Hadid Architects and Arup won the RIBA Stirling Prize in 2011.[48]

Arup was named Tunnel Design Firm of the Year at the 2012 ITA AITES International Tunnelling Awards.[49]

Arup was awarded Infrastructure Architect of the Year at the 2020 Architect of the Year Awards.[50]

Arup was awarded Britains Most Admired Company 2021 by Management Today[51]

Awards to Arup employees

[edit]Barbara Lane, associate director with Arup, won the Royal Academy of Engineering Silver Medal in 2008[52] for her outstanding contribution to British engineering on design of structures for fire. Rogier van der Heide, at that time Director of Arup and the firm's global leader of the lighting design business, received the Radiance Award, the world's most prestigious lighting design prize presented by the International Association of Lighting Designers[53]

Fellows

[edit]Arup Fellow is a lifelong honorary title awarded to selected honorary individuals in the firm. It acknowledges the highest design and technical achievements of people, not only within the firm, but also in the industry as a whole. They are considered role models who possess world-class expertise who put theory into effective practice.

The current fellows, as of April 2024, are:[54]

- Alice Chow

- Alisdair McGregor

- Alison Norrish

- Alistair Guthrie

- Andrew Allsop

- Andrew Lawrence

- Andy Sedgwick

- Atila Zekioglu

- Barbara Lane

- Brian Simpson OBE

- Brian Stacy

- Bruce Chong

- Chris Luebkeman

- Corinne Swain OBE (d. 2020)[55]

- Craig Gibbons

- Davar Abi-Zadeh

- David Caiden

- Dinesh Patel

- Duncan Nicholson

- Erin McConahey

- Fiona Cousins

- Florence Lam

- Geoffrey Tai

- Goman Ho

- Graham Dodd

- Haico Schepers

- Helen Campbell

- Ian Feltham

- Ian Gardner

- Jon Hurt

- Jo da Silva OBE

- Justin Abbott

- Kym Burgemeister

- Liu Peng

- Mahadev Raman

- Malcolm Smith

- Marianne Foley

- Mark Chown

- Mark Fletcher

- Mathew Vola

- Matt Carter

- Melissa Burton

- Michael Beaven

- Michael Willford

- Mike Glover OBE

- Naeem Hussain

- Nick O'Riordan

- Paul Johnson

- Paul Sloman

- Peter Burnton

- Peter Gist

- Peter Johnson

- Raj Patel

- Regine Weston

- Richard Greer

- Richard Hornby

- Richard Sturt

- Rory McGowan

- Rudi Scheuermann

- Sam Chow

- Sowmya Parthasarathy

- Susan Lamont

- Tateo Nakajima

- Tim Suen

- Tony Vidago

- Tristram Carfrae

- Vincent Cheng

- Wilfred Lau

Notable alumni and current staff

[edit]- Sir Ove Nyquist Arup (1895–1988), structural engineer and philosopher, founder of the company, recipient of the RIBA Royal Gold Medal for Architecture 1966, Institution of Structural Engineers Gold Medal 1973.[56]

- Peter Dunican (1918–1989), structural engineer, first chairman of Ove Arup Partnership (1977–1984), and President of the Institution of Structural Engineers in 1977 and 1978.

- Sir Jack Zunz (1923–2018), civil engineer, and principal structural designer of the Sydney Opera House, IStructE Gold Medal 1988.[57]

- Sir Philip Dowson (1924–2014), architect, founding partner of Arup Associates, Royal Gold Medal 1981, and President of the Royal Academy 1993–1999.[58]

- Povl Ahm (1926–2005), structural engineer, principal engineer for Coventry Cathedral, and chairman of Ove Arup & Partners 1984–1992.[59]

- Professor Sir Ted Happold (1930–1996), structural engineer, executive partner for the Pompidou Centre, and founder of Buro Happold in 1976.[60]

- Peter Rice (1935–1992), structural engineer, responsible for the roof geometry of the Sydney Opera House and the build project for the Pompidou Centre.

- Dr Edmund Hambly (1942–1995), structural engineer, and president of the Institution of Civil Engineers 1994–1995.

- Cecil Balmond (1943–), structural engineer, founder of Arup's Advanced Geometry Unit, lead designer for the Centre Pompidou-Metz, the CCTV tower in Beijing, the Ito-Balmond Serpentine Pavilion, and the ArcelorMittal Orbit.

- Steven Groák (1944–1998) head of research and development at Ove Arup Partnership from 1990 to 1998.

- Mike Glover (1946–), civil and structural engineer, technical director for the Channel Tunnel Rail Link, and recipient of IStructE Gold Medal 2008.

- Tony Fitzpatrick (1950–2003), structural engineer, and leader of the Millennium Bridge damping project.

- Sir Philip Dilley (1955–), civil engineer, Arup Group chairman 2009–2014, chairman of London First, chairman of the Infrastructure and Urban Development Community at the World Economic Forum.

- Professor Chris Wise (1956–), structural engineer, and later Professor of Creative Design at Imperial College. He was one of the founders of Expedition Engineering in 1999.

- Nille Juul-Sørensen (1958–), renown global product designer.

- Tristram Carfrae (1959–), IStructE Gold Medal 2014.

- Tim Jarvis (1966–), environmental scientist, author and explorer.

- Jo da Silva (1967–), IStructE Gold Medal 2017.

- Rogier van der Heide (1970–), lighting designer, and former leader of Arup's lighting consultancy, and later chief design officer at Philips Lighting.

Related companies

[edit]Companies under Arup Group

- Oasys Ltd, established in 1976 as the software house of Arup, providing engineering software for structural, geotechnical and pedestrian movement simulation/analysis software.

Several staff have left to form other companies, often with significant parallels with Arup.

- In 1976, Edmund Happold (engineer for the Pompidou Centre) and six other engineers left Arup to form Buro Happold in Bath.

- Mark Whitby left Buro Happold to form Whitby Bird.

- In 1999, Chris Wise (engineer for the Millennium Bridge) and Sean Walsh left Arup to form Expedition Engineering in London.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e "Arup Financial statements 2022". arup.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ "Arup Financial Statements 2022 - Arup". www.arup.com. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 27 March 2023.

- ^ "The history of Arup - Arup". www.arup.com. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "How Arup Became The Go-To Firm for Architecture's Most Ambitious Projects". ArchDaily. 16 September 2013. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Volner, Ian (16 September 2013). "How Arup Became The Go-To Firm for Architecture's Most Ambitious Projects". archdaily.com. Archived from the original on 9 July 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Corporate Report 2008, section 23 (Report). The Arup Group. p. 19.

Arup Group Ltd is owned by the Ove Arup Partnership Employee Trust, the Ove Arup Partnership Charitable Trust and the Arup Service Trust.

- ^ "Arup Structure". The Arup Group. Archived from the original on 1 November 2009. Retrieved 25 November 2009.

- ^ Odoi, Antoinette (20 August 2007). "Firms owned by staff have beaten the FTSE all-share". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 May 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "V&A · Engineering the Penguin Pool at London Zoo". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 14 June 2023. Retrieved 2 September 2021.

- ^ "Arup Associates". historicengland.org.uk. 15 June 2018. Archived from the original on 13 June 2023. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Alexandra Wynne (3 August 2016). "Arup's total design legacy". New Civil Engineer. Archived from the original on 13 June 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ "Sir Philip Dowson - obituary". www.telegraph.co.uk. 14 September 2014. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ Ove Arup & Partners 1946–1986. London: Academy Editions. 1986. ISBN 0-85670-898-4.

- ^ Campbell, Peter; Allan, John; Ahrends, Peter; Zunz, Jack; Morreau, Patrick (1995). Ove Arup 1895–1988. London: Institution of Civil Engineers. ISBN 0-7277-2066-X.

- ^ Jones, Peter (2006). Ove Arup, Master Builder of the Twentieth Century. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11296-2.

- ^ Hunt, Tony (October 2001). "Utzon's Sphere: Sydney Opera House—How It Was Designed and Built—Review". EMAP Architecture, Gale Group. Archived from the original on 19 December 2006. Retrieved 30 January 2007.

- ^ "V&A · Computers and the Sydney Opera House". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 14 September 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ "Centre Pompidou: high-tech architecture's inside-out landmark". Dezeen. 5 November 2019. Archived from the original on 5 July 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ "The construction of the HSBC building in Hong Kong – The Industrial History of Hong Kong Group". industrialhistoryhk.org. Archived from the original on 21 June 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ "Ove Arup Key Speech - Arup". www.arup.com. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ "V&A · Engineering the World: Ove Arup and the Philosophy of Total Design - Exhibition at South Kensington". Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 14 September 2021. Retrieved 14 September 2021.

- ^ Easen, Nick (3 November 2019). "Employee ownership: how Arup's CFO stays ahead of the curve". Raconteur. Archived from the original on 18 August 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "The Politics of Power". The Brits who Built the Modern World. London. 27 February 2014. BBC Four. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ^ Earley, Katharine (16 May 2013). "Arup: sustainability shapes every project". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "Dongtan Eco-City in China designed by Arup - Verdict Designbuild". www.designbuild-network.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ Marshall2020-08-28T06:00:00+01:00, Jordan. "Arup's HS2 Interchange station approved". Building Design. Archived from the original on 28 January 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Arup Partnership". Habitat for Humanity Australia. 16 September 2021. Archived from the original on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "WaterAid joins forces with Arup | WaterAid Australia". www.wateraid.org. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "Generous UK donors can be proud of post-tsunami reconstruction | Disasters Emergency Committee". www.dec.org.uk. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "LocalGov.co.uk - Your authority on UK local government - Government appoints Arup-led consortium for £3.6bn Towns Fund delivery". www.localgov.co.uk. 15 June 2020. Archived from the original on 24 June 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ UCL (15 July 2009). "UCL signs agreement with Arup". UCL News. Archived from the original on 23 June 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ "High Roller Observation Wheel". London: Arup. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Alshangiti, Mohammed. "Link to press release - project overview". Company website. Archived from the original on 1 March 2021.

- ^ "The Singapore Flyer and design of Giant Observation Wheels"Brendon McNiven & Pat Dallard, IStructE Asia-Pacific Forum on Structural Engineering: Innovations in Structural Engineering, Singapore, 2 – 3 November 2007

- ^ "Ahmed Adnan Saygun Arts Centre". arup.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ a b c "Arup Sport". arup.com. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ Rayner, Gordon (7 August 2008). "Beijing Olympics: The Bird's Nest stadium". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2011.

- ^ "Australia's CSR Top 10". Pro Bono Australia. Archived from the original on 28 September 2021. Retrieved 22 September 2021.

- ^ Basulto, David (3 October 2013). "Winners of the World Architecture Festival 2013". archdaily.com. Archived from the original on 1 February 2020. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Stirling prize 2007". The Guardian. 26 July 2007. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "World Architecture Awards" (Press release). Arup. 5 August 2002. Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- ^ "The Worldaware Award for Innovation". Worldaware. 2002. Archived from the original on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- ^ "Gold Medal for Architecture". National Eisteddfod of Wales. Archived from the original on 24 January 2021.

- ^ "Innovation key to FSE Design Award winners". FSE: Fire Safety Engineering. 15 November 2006. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- ^ "Fire Safety Engineering Design Awards". Arup. 8 November 2006. Archived from the original on 21 February 2007. Retrieved 27 March 2007.

- ^ "Arup success at the RTPI Awards". The Arup Group. 17 February 2009. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Live Design's Excellence in Live Design Award (Theatre)". Live Design/Penton Media. 2010. Archived from the original on 7 May 2010. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- ^ Griffiths, Alyn (1 October 2011). "Evelyn Grace Academy by Zaha Hadid Architects wins RIBA Stirling Prize". dezeen.com. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Maloney, Rebecca (11 December 2012). "Arup named Tunnel Design Firm of 2012". The Arup Group. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Wright, Sarah (26 October 2020). "Arup named 'Infrastructure Architect of the Year' 2020". The Arup Group. Archived from the original on 20 April 2021. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ "Arup revealed as Britain's Most Admired Company". www.managementtoday.co.uk. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "Less is more for fire protection". Royal Academy of Engineering. 5 June 2008. Archived from the original on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 3 July 2008.

- ^ "Rogier van der Heide". Architect Magazine. 8 March 2007. Retrieved 5 August 2024.

- ^ "Arup Fellows". Arup. arup.com. 8 May 2024. Archived from the original on 8 April 2024. Retrieved 8 April 2024.

- ^ Sue Manns, "Presidential team continues to raise profile of planning", RTPI, 17 March 2020 Archived 26 July 2020 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 31 March 2020

- ^ Bevan, Robert (8 June 2016). "Ove Arup: the man who made engineering creative". www.standard.co.uk. Archived from the original on 15 March 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Harwood, Elain (2 January 2019). "Sir Jack Zunz obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 January 2019. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Glancey, Jonathan (5 September 2014). "Sir Philip Dowson obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 September 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ "Povl Ahm". the Times. 4 June 2005. Archived from the original on 21 October 2021. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

- ^ Sharpe, Dennis (23 October 2011). "OBITUARY: Professor Sir Edmund Happold". The Independent. Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2021.

External links

[edit]Arup (buildings and structures).

- Official website

- Innovation at Arup (archived)

- Arup Americas online magazine. Archived 20 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine.

- Ove Arup

- Architecture firms based in London

- Business services companies of the United Kingdom

- Construction and civil engineering companies established in 1946

- Construction and civil engineering companies of the United Kingdom

- Denmark–United Kingdom relations

- Design companies established in 1946

- Employee-owned companies of the United Kingdom

- Engineering consulting firms of the United Kingdom

- International engineering consulting firms

- 1946 establishments in England

- IStructE Supreme Award laureates

- British companies established in 1946