Hodegetria

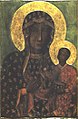

A Hodegetria,[a] or Virgin Hodegetria, is an iconographic depiction of the Theotokos (Virgin Mary) holding the Child Jesus at her side while pointing to him as the source of salvation for humankind. The Virgin's head usually inclines towards the child, who raises his hand in a blessing gesture. Metals are often used to draw attention to young Christ, reflecting light and shining in a way to embody divinity.[1] In the Western Church this type of icon is sometimes called Our Lady of the Way.

The most venerated icon of the Hodegetria type, regarded as the original, was displayed in the Monastery of the Panaghia Hodegetria in Constantinople, which was built specially to contain it. Unlike most later copies it showed the Theotokos standing full-length. It was said to have been brought back from the Holy Land by Eudocia, the wife of emperor Theodosius II (408–450), and to have been painted by Saint Luke the evangelist, the attributed author of the Gospel of Luke.[2] The icon was double-sided,[3] with a crucifixion on the other side, and was "perhaps the most prominent cult object in Byzantium".[4]

The original icon has probably now been lost, although various traditions claim that it was carried to Russia or Italy. There are a great number of copies of the image, including many of the most venerated of Russian icons, which have themselves acquired their own status and tradition of copying.

Constantinople

[edit]There are a number of images showing the icon in its shrine and in the course of being displayed publicly, which happened every Tuesday, and was one of the great sights of Constantinople for visitors. After the Fourth Crusade, from 1204 to 1261, it was moved to the Monastery of the Pantocrator, which had become the cathedral of the Venetian see during the period of Frankish rule, and since none of the illustrations of the shrine at the Hodegetria Monastery predate this interlude, the shrine may have been created after its return.[5]

There are a number of accounts of the weekly display, the two most detailed by Spaniards:

Every Tuesday twenty men come to the church of Maria Hodegetria; they wear long red linen garments,[6] covering up their heads like stalking clothes […] there is a great procession and the men clad in red go one by one up to the icon; the one with whom the icon is pleased is able to take it up as if it weighed almost nothing. He places it on his shoulder and they go chanting out of the church to a great square, where the bearer of the icon walks with it from one side to the other, going fifty times around the square. When he sets it down then others take it up in turn.[7]

Another account says the bearers staggered around the crowd, the icon seeming to lurch towards onlookers, who were then considered blessed by the Virgin. Clergy touched pieces of cotton-wool to the icon and handed them out to the crowd. A wall-painting in a church near Arta in Greece shows a great crowd watching such a display, whilst a street-market for unconcerned locals continues in the foreground.[8]

The Hamilton Psalter picture of the shrine in the monastery appears to show the icon behind a golden screen of large mesh, mounted on brackets rising from a four-sided pyramidal base, like many large medieval lecterns. The heads of the red-robed attendants are level with the bottom frame of the icon.[9]

The icon disappeared during the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 when it was deposited at the Chora Church. It may have been cut into four pieces.[10]

Spread of the image

[edit]

In the 10th century, after the period of iconoclasm in Byzantine art, this image became more widely used, possibly developing from an earlier type where the Virgin's right hand was on Christ's knee.[11] An example of this earlier type is the Salus Populi Romani icon in Rome. Many versions carry the inscription "Hodegetria" in the background and in the Byzantine context "only these named versions were understood by their medieval audience as conscious copies of the original Hodegetria in the Hodegon monastery", according to Maria Vasilakē.[12]

Full-length versions, both probably made by Greek artists, appear in mosaic in Torcello Cathedral (12th century) and the Cappella Palatina, Palermo (c. 1150), this last with the "Hodegetria" inscription.[13]

From the Hodegetria developed the Panagia Eleousa (Virgin of Tender Mercy), where Mary still indicates Christ, but he is nuzzling her cheek, which she slightly inclines towards him; famous versions include the Theotokos of Vladimir and the Theotokos of St. Theodore. Usually Christ is on the left in these images.

Hodegetria of Smolensk

[edit]

Some Russians, however, believe that after the fall of Constantinople, St. Luke's icon surfaced in Russia, where it was placed in the Assumption Cathedral in Smolensk, Russia. On several occasions, it was brought with great ceremony to Moscow, where the Novodevichy Convent was built in her honour. Her feast day is August 10.

This icon, dated by art historians to the 11th century, is believed to have been destroyed by fire during the German occupation of Smolensk in 1941. A number of churches all over Russia are dedicated to the Smolensk Hodegetria, e.g., the Smolensky Cemetery Church in St. Petersburg and the Odigitrievsky Cathedral in Ulan-Ude. They may refer to the Theotokos as "Our Lady of Smolensk."

Italian tradition

[edit]An Italian tradition relates that the original icon of Mary attributed to Luke, sent by Eudocia to Pulcheria from Palestine, was a large circular icon only of her head. When the icon arrived in Constantinople, it was fitted in as the head in a very large rectangular icon of Mary holding the Christ child; it is this composite icon that became the one historically known as the Hodegetria. Another tradition states that when the last Latin Emperor of Constantinople, Baldwin II, fled Constantinople in 1261, he took this original circular portion of the icon with him. It remained in the possession of the Angevin dynasty, who likewise had it inserted into a larger image of Mary and the Christ child, which is presently enshrined above the high altar of the Benedictine Abbey church of Montevergine.[14][15] Unfortunately, over the centuries this icon has been subjected to repeated repainting, so that it is difficult to determine what the original image of Mary's face would have looked like. However, Guarducci also claims that in 1950 an ancient image of Mary[16] at the Church of Santa Francesca Romana was determined to be a very exact, but reverse mirror image of the original circular icon that was made in the 5th century and brought to Rome, where it has remained until the present.[17]

An Italian "original" icon of the Hodegetria in Rome features in the crime novel Death and Restoration (1996) by Iain Pears, in the Jonathan Argyll series of art history mysteries.

It gives its name to the church of Santa Maria Odigitria al Tritone in Rome.

The Italian tradition spread also to Malta in the sixteenth century and the Chapel of Our Lady of Itria is dedicated to the Hodegetria.[18]

Gallery

[edit]Eastern church

[edit]-

Full-length mosaic by Greek artists, Torcello, 12th century

-

The Theotokos of Tikhvin (c. 1300)

-

The Theotokos of Perivleptos (c. 1350)

-

The Theotokos of the Passion (17th century)

-

Christodoulos Kalergis (18th century)

Western church

[edit]-

Duccio, 1284

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Koinē Greek: Ὁδηγήτρια, romanized: Hodēgḗtria, lit. 'She who points the Way' Koinē Greek: [(h)o.d̪e̝ˈɡˠe̝.tri.a], Modern Greek pronunciation: [o̞.ðiˈʝi.tri.ɐ];

Russian: Одиги́трия, romanized: Odigítria Russian pronunciation: [ɐ.dʲɪˈɡʲi.trʲɪ.jə]; Romanian: Hodighitria

- ^ Pentcheva, Bissera V. (2006). "The Performative Icon". The Art Bulletin. 88 (4): 633. doi:10.1080/00043079.2006.10786312.

- ^ James Hall, A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, p. 91, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0-7195-3971-4

- ^ Vasilakē; op & page cit

- ^ Cormack: 58

- ^ Cormack

- ^ Perhaps a lay confraternity – they are shown inside the shrine in a manuscript illumination in the Hamilton Psalter of c. 1300 (Berlin), Cormack illustration 9

- ^ Cormack:59-61 – Pero Tafur in 1437

- ^ Cormack: illustration p.60

- ^ Cormack:61 for display, 58 and illustration 9 for shrine

- ^ Warren Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and Society, Stanford, 1997 ISBN 0-8047-2630-2. Four pieces from Cormack: 59

- ^ Maria Vasilakē, p. 196

- ^ Vasilakē; op and page cit

- ^ James Hall, A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, p. 126, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0-7195-3971-4

- ^ "Image: madonna.jpg, (300 × 556 px)". avellinomagazine.it. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- ^ "Image: Montevergine4.jpg, (238 × 340 px)". mariadinazareth.it. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- ^ "Image: icona sta maria nuova.jpg, (350 × 502 px)". vultus.stblogs.org. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- ^ Margherita Guarducci, The Primacy of the Church of Rome. San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1991, 93–101.

- ^ Brincat, Joe. "MGR Tal-Itria". www.kappellimaltin.com. Retrieved 2023-11-12.

References

[edit]- Cormack, Robin (1997). Painting the Soul: Icons, Death Masks and Shrouds. London: Reaktion Books.

- Kurpik, Wojciech (2008). "Częstochowska Hodegetria" (in Polish, English, and Hungarian). Łódź-Pelplin: Wydawnictwo Konserwatorów Dzieł Sztuki, Wydawnictwo Bernardinum. p. 302. Archived from the original on 2011-05-18. Retrieved 2011-03-31.

- Vasilakē, Maria (2004). Images of the Mother of God: Perceptions of the Theotokos in Byzantium. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing Co. p. 196. ISBN 0-7546-3603-8. OCLC 1124558394.

External links

[edit]- Byzantium: Faith and Power (1261–1557), an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains many examples of Hodegetria