8½

| 8½ | |

|---|---|

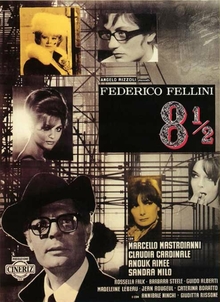

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Federico Fellini |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by |

|

| Produced by | Angelo Rizzoli |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gianni Di Venanzo |

| Edited by | Leo Catozzo |

| Music by | Nino Rota |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 138 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Language | Italian |

| Box office | $3.5 million (US/Canada rentals)[2] |

8½ (Italian: Otto e mezzo [ˈɔtto e mˈmɛddzo]) is a 1963 comedy drama film co-written and directed by Federico Fellini. The metafictional narrative centers on Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni), a famous Italian film director who suffers from stifled creativity as he attempts to direct an epic science fiction film. Claudia Cardinale, Anouk Aimée, Sandra Milo, Rossella Falk, Barbara Steele, and Eddra Gale portray the various women in Guido's life. The film was shot in black and white by cinematographer Gianni Di Venanzo and features a score by Nino Rota, with costume and set designs by Piero Gherardi.

8½ was critically acclaimed and won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Costume Design (black-and-white). It is acknowledged as an avant-garde film[3] and a highly influential classic. It was ranked 10th on the British Film Institute's The Sight & Sound Greatest Films of All Time 2012 critics' poll and 4th by directors.[4][5] It is included in the Vatican's compilation of 45 important films made before 1995, the 100th anniversary of cinema.[6] The film ranked 7th in BBC's 2018 list of The 100 Greatest Foreign Language Films voted by 209 film critics from 43 countries around the world.[7]

It was included on the Italian Ministry of Cultural Heritage's 100 Italian films to be saved, a list of 100 films that "have changed the collective memory of the country between 1942 and 1978".[8] It is considered to be one of the greatest and most influential films of all time.

Plot

[edit]Guido Anselmi, a famous Italian film director, is suffering from "director's block". Stalled on his new science fiction film that includes thinly veiled autobiographical references, he has lost interest amidst artistic and marital difficulties. While attempting to recover from his anxieties at a luxurious spa, Guido hires a well-known critic to review his ideas for his film, but the critic blasts them. Guido has recurring visions of an Ideal Woman, whom he sees as key to his story. His mistress Carla comes to visit him, but Guido puts her in a separate hotel. The film production crew relocates to Guido's hotel in an unsuccessful attempt to get him to work on the film.

Guido admits to a cardinal that he is not happy. The cardinal offers little insight. Guido invites his estranged wife Luisa and her friends to join him. They dance, but Guido abandons her for his production crew. Guido confesses to his wife's best friend Rosella that he wanted to make a film that was pure and honest, but he is struggling with something honest to say. Carla surprises Guido, Luisa, and Rosella outside the hotel, and Guido claims that he and Carla ended their affair years earlier. Luisa and Rosella call him on the lie, and Guido slips into a fantasy world where he lords over a harem of women from his life, but a rejected showgirl starts a rebellion. The fantasy women attack Guido with harsh truths about himself and his sex life.

When Luisa sees how bitterly Guido represents her in the film, she declares that their marriage is over. Guido's Ideal Woman arrives in the form of an actress named Claudia. Guido explains that his film is about a burned-out man who finds salvation in this Ideal Woman. Claudia concludes that the protagonist is unsympathetic because he is incapable of love. Broken, Guido calls off the film, but the producer and the film's staff announce a press conference. Guido attempts to escape from the journalists and eventually imagines shooting himself in the head. Guido realizes he was attempting to solve his personal confusion by creating a film to help others, when instead he needs to accept his life for what it is. He asks Luisa for her assistance in doing so. Carla tells him that she figured out what he was trying to say: that Guido cannot do without the people in his life. The men and women hold hands and walk briskly around the circle with Guido and Luisa joining them last.

Cast

[edit]- Marcello Mastroianni as Guido Anselmi, a film director

- Claudia Cardinale as Claudia, a film star Guido casts as his Ideal Woman

- Anouk Aimée as Luisa Anselmi, Guido's estranged wife

- Sandra Milo as Carla, Guido's mistress

- Rossella Falk as Rossella, Luisa's best friend and Guido's confidante

- Barbara Steele as Gloria Morin, Mezzabotta's new young girlfriend

- Madeleine Lebeau as Madeleine, a French actress

- Caterina Boratto as a mysterious lady in the hotel

- Eddra Gale as La Saraghina, a prostitute

- Guido Alberti as Pace, a film producer

- Mario Conocchia as a fictionalized version of himself, Guido's production assistant

- Bruno Agostini as a fictionalized version of himself, the production director

- Cesarino Miceli Picardi as a fictionalized version of himself, the production supervisor

- Jean Rougeul as Carini Daumier, a film critic

- Mario Pisu as Mario Mezzabotta, Guido's friend

- Yvonne Casadei as Jacqueline Bonbon, a former cabaret dancer

- Ian Dallas as Maurice, Maya's assistant

- Mino Doro as Alberto, Claudia's agent

- Nadia Sanders as Nadine

- Edy Vessel as a mannequin

- Eugene Walter as an American journalist

- Mary Indovino as Maya, the clairvoyant

- Giuditta Rissone as Guido's mother

- Annibale Ninchi as Guido's father

- Olimpia Cavalli as Olimpia (uncredited)

- Ferdinand Guillaume as the clown (uncredited)

- Maria Antonietta Beluzzi as a prostitute (uncredited)

Themes

[edit]8½ is about the struggles involved in the creative process, both technical and personal, and the problems artists face when expected to deliver something personal and profound with intense public scrutiny, on a constricted schedule, while simultaneously having to deal with their own personal relationships. It is, in a larger sense, about the search for meaning within a difficult, fragmented life. Like several Italian films of the period (most evident in the films of Fellini's contemporary, Michelangelo Antonioni), 8½ also is about the alienating effects of modernization.[9]

At this point, Fellini had directed six feature films: Lo sceicco bianco (1952), I Vitelloni (1953), La Strada (1954), Il bidone (1955), Le notti di Cabiria (1957), and La Dolce Vita (1960). He had co-directed Luci del varietà (Variety Lights) (1950) with Alberto Lattuada, and had directed two short segments, Un'Agenzia Matrimoniale (A Marriage Agency) in the omnibus film L'amore in città (Love in the City) (1953) and Le Tentazioni del Dottor Antonio from the omnibus film Boccaccio '70 (1962). The title is in keeping with Fellini's self-reflexive theme: by his count it was his eighth-and-a-half film.[10] The working title for 8½ was La bella confusione (The Beautiful Confusion) proposed by co-screenwriter, Ennio Flaiano, but Fellini then "had the simpler idea (which proved entirely wrong) to call it Comedy".[11]

According to Italian writer Alberto Arbasino, 8½ used techniques similar to, and has parallels with, Robert Musil's novel The Man Without Qualities (1930).[12]

The film is unusual in that it is a film about making a film, and the film that is being made is the film that the audience is viewing. An example is the dream sequence of "Guido's Harem" where Guido is bathed and carried in white linen by all the women from the film, only to have the women protest for being sent to live upstairs in the house when they turn 30, and "Jacquilene Bonbon" does her last dance. The Guido's Harem scene is immediately followed by the "Screen Test" depicting the same actors in a theater, each taking the stage for a screen test, being chosen to act for the very scene the audience just watched. This mirror of mirrors is further emphasized at the end where the director Guido sits at the table of the press conference, where the entire table is a mirror reflecting the director in it.

Production

[edit]

In an October 1960 letter to his colleague Brunello Rondi, Fellini first outlined his film ideas about a man suffering from a creative block: "Well then—a guy (a writer? any kind of professional man? a theatrical producer?) has to interrupt the usual rhythm of his life for two weeks because of a not-too-serious disease. It's a warning bell: something is blocking up his system."[13] Unclear about the script, its title, and his protagonist's profession, he scouted locations throughout Italy "looking for the film"[14] in the hope of resolving his confusion. Flaiano suggested La bella confusione (literally The Beautiful Confusion) as the film's title. Under pressure from his producers, Fellini finally settled on 8½, a self-referential title referring principally (but not exclusively)[15] to the number of films he had directed up to that time.

Giving the order to start production in spring 1962, Fellini signed deals with his producer Rizzoli, fixed dates, had sets constructed, cast Mastroianni, Anouk Aimée, and Sandra Milo in lead roles, and did screen tests at the Scalera Studios in Rome. He hired cinematographer Gianni Di Venanzo, among key personnel. But apart from naming his hero Guido Anselmi, he still could not decide what his character did for a living.[16] The crisis came to a head in April when, sitting in his Cinecittà office, he began a letter to Rizzoli confessing he had "lost his film" and had to abandon the project. Interrupted by the chief machinist requesting he celebrate the launch of 8½, Fellini put aside the letter and went on the set. Raising a toast to the crew, he "felt overwhelmed by shame... I was in a no exit situation. I was a director who wanted to make a film he no longer remembers. And lo and behold, at that very moment everything fell into place. I got straight to the heart of the film. I would narrate everything that had been happening to me. I would make a film telling the story of a director who no longer knows what film he wanted to make".[17]

When shooting began on 9 May 1962, Eugene Walter recalled Fellini taking "a little piece of brown paper tape" and sticking it near the viewfinder of the camera. Written on it was Ricordati che è un film comico ("Remember that this is a comic film").[18] Perplexed by the seemingly chaotic, incessant improvisation on the set, Deena Boyer, the director's American press officer at the time, asked for a rationale. Fellini told her that he hoped to convey the three levels "on which our minds live: the past, the present, and the conditional - the realm of fantasy".[19]

8½ was filmed in the spherical cinematographic process, using 35-millimeter film, and exhibited with an aspect ratio of 1.85:1. As with most Italian films of this period, the sound was entirely dubbed in afterwards; following a technique dear to Fellini, many lines of the dialogue were written only during post production, while the actors on the set mouthed random lines. 8½ marks the first time that actress Claudia Cardinale was allowed to dub her own dialogue; previously her voice was thought to be too throaty and, coupled with her Tunisian accent, was considered undesirable.[20] This is Fellini's last black-and-white film.[21]

In September 1962, Fellini shot the end of the film as initially written: Guido and his wife sit together in the restaurant car of a train bound for Rome. Lost in thought, Guido looks up to see all the characters of his film smiling ambiguously at him as the train enters a tunnel. Fellini then shot an alternative ending set around the spaceship on the beach at dusk but with the intention of using the scenes as a trailer for promotional purposes only. In the 2002 documentary Fellini: I'm a Born Liar, co-scriptwriter Tullio Pinelli explains how he warned Fellini to abandon the train sequence with its implicit theme of suicide for an upbeat ending.[22] Fellini accepted the advice, using the alternative beach sequence as a more harmonious and exuberant finale.[23]

After shooting wrapped on 14 October, Nino Rota composed various circus marches and fanfares that would later become signature tunes of the maestro's cinema.[24]

Soundtrack

[edit]| No. | Title | Composer |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | La Passerella di Otto e Mezzo | Nino Rota |

| 2a. | Cimitero | Nino Rota |

| 2b. | Gigolette | Franz Lehár |

| 2c. | Cadillac / Carlotta's Galop | Nino Rota |

| 3. | E Poi (Walzer) | Nino Rota |

| 4. | L'Illusionista | Nino Rota |

| 5. | Concertino Alle Terme | Gioachino Rossini and Piotr I. Tchaikovsky |

| 6. | Nell'Ufficio Produzione di Otto e Mezzo | Nino Rota |

| 7. | Ricordi d'Infanza - Discesa al Fanghi | Nino Rota |

| 8. | Guido e Luiza - Nostalgico Swing | Nino Rota |

| 9. | Carlotta's Galop | Nino Rota |

| 10. | L'Harem | Nino Rota |

| 11a. | Rivolta nell'Harem | Richard Wagner |

| 11b. | La Ballerina Pensionata (Ça C'Est Paris) | José Padilla Sánchez |

| 11c. | La Conferenza Stampa del Regista | Nino Rota |

| 12. | La Passerella di Addio | Nino Rota |

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]First released in Italy on 14 February 1963, 8½ received widespread acclaim, with reviewers hailing Fellini as "a genius possessed of a magic touch, a prodigious style".[24] Italian novelist and critic Alberto Moravia described the film's protagonist, Guido Anselmi, as "obsessed by eroticism, a sadist, a masochist, a self-mythologizer, an adulterer, a clown, a liar and a cheat. He's afraid of life and wants to return to his mother's womb ... In some respects, he resembles Leopold Bloom, the hero of James Joyce's Ulysses, and we have the impression that Fellini has read and contemplated this book. The film is introverted, a sort of private monologue interspersed with glimpses of reality .... Fellini's dreams are always surprising and, in a figurative sense, original, but his memories are pervaded by a deeper, more delicate sentiment. This is why the two episodes concerning the hero's childhood at the old country house in Romagna and his meeting with the woman on the beach in Rimini are the best of the film, and among the best of all Fellini's works to date".[25]

Reviewing for Corriere della Sera, Giovanni Grazzini underlined that "the beauty of the film lies in its 'confusion'... a mixture of error and truth, reality and dream, stylistic and human values, and in the complete harmony between Fellini's cinematographic language and Guido's rambling imagination. It is impossible to distinguish Fellini from his fictional director and so Fellini's faults coincide with Guido's spiritual doubts. The osmosis between art and life is amazing. It will be difficult to repeat this achievement.[26] Fellini's genius shines in everything here, as it has rarely shone in the movies. There isn't a set, a character or a situation that doesn't have a precise meaning on the great stage that is 8½".[27] Mario Verdone of Bianco e Nero insisted the film was "like a brilliant improvisation ... The film became the most difficult feat the director ever tried to pull off. It is like a series of acrobats [sic] that a tightrope walker tries to execute high above the crowd, ... always on the verge of falling and being smashed on the ground. But at just the right moment, the acrobat knows how to perform the right somersault: with a push he straightens up, saves himself and wins".[28]

8½ screened at the 1963 Cannes Film Festival in April to "almost universal acclaim"[29] and was Italy's official entry in the later 3rd Moscow International Film Festival where it won the Grand Prize. French film director François Truffaut wrote: "Fellini's film is complete, simple, beautiful, honest, like the one Guido wants to make in 8½".[30] Premier Plan critics André Bouissy and Raymond Borde argued that the film "has the importance, magnitude, and technical mastery of Citizen Kane. It has aged twenty years of the avant-garde in one fell swoop because it both integrates and surpasses all the discoveries of experimental cinema".[31] Pierre Kast of Les Cahiers du cinéma explained that "my admiration for Fellini is not without limits. For instance, I did not enjoy La Strada but I did I Vitelloni. But I think we must all admit that 8½, leaving aside for the moment all prejudice and reserve, is prodigious. Fantastic liberality, a total absence of precaution and hypocrisy, absolute dispassionate sincerity, artistic and financial courage these are the characteristics of this incredible undertaking".[32] The film ranked 10th on Cahiers du Cinéma's Top 10 Films of the Year List in 1963.[33]

Released in the United States on 25 June 1963 by Joseph E. Levine, who had bought the rights sight unseen, the film was screened at the Festival Theatre in New York City in the presence of Fellini and Marcello Mastroianni. The acclaim was unanimous with the exception of reviews by Judith Crist, Pauline Kael, and John Simon. Crist "didn't think the film touched the heart or moved the spirit".[29] Kael derided the film as a "structural disaster" while Simon considered it "a disheartening fiasco".[34][35] Newsweek defended the film as "beyond doubt, a work of art of the first magnitude".[29] Bosley Crowther praised it in The New York Times as "a piece of entertainment that will really make you sit up straight and think, a movie endowed with the challenge of a fascinating intellectual game ... If Mr. Fellini has not produced another masterpiece – another all-powerful exposure of Italy's ironic sweet life – he has made a stimulating contemplation of what might be called, with equal irony, a sweet guy".[36] Archer Winsten of the New York Post interpreted the film as "a kind of review and summary of Fellini's picture-making" but doubted that it would appeal as directly to the American public as La Dolce Vita had three years earlier: "This is a subtler, more imaginative, less sensational piece of work. There will be more people here who consider it confused and confusing. And when they do understand what it is about – the simultaneous creation of a work of art, a philosophy of living together in happiness, and the imposition of each upon the other, they will not be as pleased as if they had attended the exposition of an international scandal".[37] Audiences, however, loved it to such an extent that a company attempted to obtain the rights to mass-produce Guido Anselmi's black director's hat.[34]

Fellini biographer Hollis Alpert noted that in the months following its release, critical commentary on 8½ proliferated as the film "became an intellectual cud to chew on".[38] Philosopher and social critic Dwight Macdonald, for example, insisted it was "the most brilliant, varied, and entertaining movie since Citizen Kane".[38] In 1987, a group of thirty European intellectuals and filmmakers voted Otto e mezzo the most important European film ever made.[39] In 1993, Chicago Sun-Times film reviewer Roger Ebert wrote that "despite the efforts of several other filmmakers to make their own versions of the same story, it remains the definitive film about director's block".[40] 8½ was voted the best foreign (i.e. non-Swedish) sound film with 21 votes in a 1964 poll of 50 Swedish film professionals organized by Swedish film magazine Chaplin.[41] The Village Voice ranked the film at number 112 in its Top 250 "Best Films of the Century" list in 1999, based on a poll of critics.[42] Entertainment Weekly voted it at No. 36 on their list of 100 Greatest Movies of All Time.[43] In 2000, Ebert added it to his "Great Movies" list, calling it "the best film ever made about filmmaking", concluding "I have seen 8½ over and over again, and my appreciation only deepens. It does what is almost impossible: Fellini is a magician who discusses, reveals, explains and deconstructs his tricks, while still fooling us with them. He claims he doesn't know what he wants or how to achieve it, and the film proves he knows exactly, and rejoices in his knowledge."[44] 8½ is a fixture on the British Film Institute's Sight & Sound critics' and directors' polls of the top 10 films ever made. The film ranked 4th and 5th on critics' poll in 1972[45] and 1982[46] respectively. It ranked 2nd on the magazine's 1992[47] and 2002[48] Directors' Top Ten Poll and 8th on the 2002 Critics' Top Ten Poll.[49] It was slightly lower in the 2012 directors' poll, 4th[5] and 10th on the 2012 critics' poll.[4] The film was included in Time's All-Time 100 best movies list in 2005.[50] The film was voted at No. 46 on the list of "100 Greatest Films" by the prominent French magazine Cahiers du cinéma in 2008.[51] In 2010, the film was ranked #62 in Empire magazine's "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema".[52] It was also ranked number 1 when the Museum of Cinematography in Łódź asked 279 Polish film professionals (filmmakers, critics, and professors) to vote for the best films in 2015.[53]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 8½ has an approval rating of 97% based on 61 reviews, with an average score of 8.5/10. The site's critical consensus reads: "Inventive, thought-provoking, and funny, 8 1/2 represents the arguable peak of Federico Fellini's many towering feats of cinema."[54] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 93 out of 100 based on 23 critic's reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".[55]

Awards and nominations

[edit]8½ won two Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film and Best Costume Design (black-and-white) while garnering three other nominations for Best Director, Best Original Screenplay, and Best Art Direction (black-and-white).[56] The New York Film Critics Circle also named 8½ best foreign language film in 1964. The Italian National Syndicate of Film Journalists awarded the film all seven prizes for director, producer, original story, screenplay, music, cinematography, and best supporting actress (Sandra Milo). It also garnered nominations for Best Actor, Best Costume Design, and Best Production Design.

At the Saint Vincent Film Festival, it was awarded Grand Prize over Luchino Visconti's Il gattopardo (The Leopard). The film screened in April at the 1963 Cannes Film Festival[57] to "almost universal acclaim but no prize was awarded because it was shown outside the competition. Cannes rules demanded exclusivity in competition entries, and 8½ was already earmarked as Italy's official entry in the later Moscow festival".[58] Presented on 18 July 1963 to an audience of 8,000 in the Kremlin's conference hall, 8½ won the prestigious Grand Prize at the 3rd Moscow International Film Festival[59] to acclaim that, according to Fellini biographer Tullio Kezich, worried the Soviet festival authorities: the applause was "a cry for freedom".[34] Jury members included Stanley Kramer, Jean Marais, Satyajit Ray, and screenwriter Sergio Amidei.[60] The film was nominated for a BAFTA Award in Best Film from any Source category in 1964. It won the Best European Film Award at Bodil Awards in 1964. The film also won National Board of Review Award for Best Foreign Language Film.

Influence

[edit]Later in the year of the film's 1963 release, a group of young Italian writers founded Gruppo '63, a literary collective of the neoavanguardia composed of novelists, reviewers, critics, and poets inspired by 8½ and Umberto Eco's seminal essay, Opera aperta (Open Work).[61]

"Imitations of 8½ pile up by directors all over the world", wrote Fellini biographer Tullio Kezich.[62] The following is Kezich's short-list of the films it has inspired: Mickey One (Arthur Penn, 1965), Alex in Wonderland (Paul Mazursky, 1970), Beware of a Holy Whore (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1971), Day for Night (François Truffaut, 1974), All That Jazz (Bob Fosse, 1979), Stardust Memories (Woody Allen, 1980), Sogni d'oro (Nanni Moretti, 1981), Planet Parade (Vadim Abdrashitov, 1984), A King and His Movie (Carlos Sorín, 1986), 1993), Living in Oblivion (Tom DiCillo, 1995), 8½ Women (Peter Greenaway, 1999), and 8½ $ (Grigori Konstantinopolsky, 1999).

Martin Scorsese included 8½ on his ballot for the Sight & Sound poll.[63] In conversation with the Criterion Collection, he named it one of his favorites:

What would Fellini do after La dolce vita? We all wondered. How would he top himself? Would he even want to top himself? Would he shift gears? Finally, he did something that no one could have anticipated at the time. He took his own artistic and life situation—that of a filmmaker who had eight and a half films to his name (episodes for two omnibus films and a shared credit with Alberto Lattuada on Variety Lights counted for him as one and a half films, plus seven), achieved international renown with his last feature and felt enormous pressure when the time came for a follow-up—and he built a movie around it. 8½ has always been a touchstone for me, in so many ways—the freedom, the sense of invention, the underlying rigor and the deep core of longing, the bewitching, physical pull of the camera movements and the compositions...But it also offers an uncanny portrait of being the artist of the moment, trying to tune out all the pressure and the criticism and the adulation and the requests and the advice, and find the space and the calm to simply listen to oneself. The picture has inspired many movies over the years (including Alex in Wonderland, Stardust Memories, and All That Jazz), and we’ve seen the dilemma of Guido, the hero played by Marcello Mastroianni, repeated many times over in reality—look at the life of Bob Dylan during the period we covered in No Direction Home, to take just one example. Like with The Red Shoes, I look at it again every year or so, and it's always a different experience.[64]

Musical adaptation

[edit]The Tony-winning 1982 Broadway musical Nine (score by Maury Yeston, book by Arthur Kopit) is based on the film, underscoring Guido's obsession with women by making him the only male character. The original production, directed by Tommy Tune, starred Raúl Juliá as Guido, Anita Morris as Carla, Liliane Montevecchi as Liliane LaFleur, Guido's producer and Karen Akers as Luisa. A 2003 Broadway revival starred Antonio Banderas, Jane Krakowski, Mary Stuart Masterson and Chita Rivera. The play was adapted into a 2009 film of the same name, directed by Rob Marshall and starring Daniel Day-Lewis as Guido alongside Nicole Kidman, Marion Cotillard, Judi Dench, Kate Hudson, Penélope Cruz, Sophia Loren, and Fergie.[65]

See also

[edit]- Asa Nisi Masa

- List of Italian submissions for the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of submissions to the 36th Academy Awards for Best Foreign Language Film

- List of films considered the best

References

[edit]- ^ "8½". BFI Film & Television Database. British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 27 December 2012.

- ^ "Top Rental Films of 1963", Variety, 8 January 1964 p 37

- ^ Alberto Arbasino (1963), review of 8½ in Il Giorno, 6 March 1963

- ^ a b "The 100 Greatest Films of All Time | Sight & Sound". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012.

- ^ a b "Directors' 10 Greatest Films of All Time | Sight & Sound". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ "Vatican Best Films List". USCCB. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Foreign Language Films". bbc. 29 October 2018. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ^ "Ecco i cento film italiani da salvare Corriere della Sera". www.corriere.it. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- ^ "Screening the Past". Archived from the original on 15 September 2007. Retrieved 9 September 2007.

- ^ Bondanella, The Cinema of Federico Fellini, 175

- ^ Quoted in Kezich, 234

- ^ Gabriele Pedullà, Alberto Arbasino [2000] "Interviste –Sull'albero di ciliegie" ("On the Cherry Tree") in CONTEMPORANEA Rivista di studi sulla letteratura e sulla comunicazione, Volume 1, 2003. Q: In some of your texts written during the 60 – I'm thinking above all of Certi romanzi – critical reflections on questions of the novel [...] are always interlaced in both an implicit and explicit way with reflections on cinema. In particular, it seems to me that your affinity with Fellini is especially significant: for example, your review of Otto e mezzo in Il Giorno. A: Reading Musil, we discovered parallels and similar procedures. But without being able to establish, either then or today, how much there was of Flaiano and how much, on the other hand, was of [Fellini's] own intuition.

- ^ Affron, 227

- ^ Alpert, 159

- ^ Kezich, 234 and Affron, 3-4

- ^ Alpert, 160

- ^ Fellini, Comments on Film, 161-62

- ^ Eugene Walter, "Dinner with Fellini", The Transatlantic Review, Autumn 1964. Quoted in Affron, 267

- ^ Alpert, 170

- ^ 8½, Criterion Collection DVD, featured commentary track.

- ^ Newton, Michael (15 May 2015). "Fellini's 8½ – a masterpiece by cinema's ultimate dreamer". The Guardian.

- ^ "The suicide theme is so overwhelming," Pinelli told Fellini, "that you'll crush your film." Cited in Fellini: I'm a Born Liar (2002), directed by Damian Pettigrew.

- ^ Alpert, 174-175, and Kezich, 245. The documentary L'Ultima sequenza (2003) also discusses the lost sequence.

- ^ a b Kezich, 245

- ^ Moravia's review first published in L'Espresso (Rome) on 17 February 1963. Quoted in Fava and Vigano, 115–116

- ^ Grazzini's review first published in Corriere della Sera (Milan) on 16 February 1963. Quoted in Fava and Vigano, 116

- ^ This translation of Grazzini's review quoted in Affron, 255

- ^ Affron, 255

- ^ a b c Alpert, 180

- ^ Truffaut's review first published in Lui (Paris), 1 July 1963. Affron, 257

- ^ First published in Premier Plan (Paris), 30 November 1963. Affron, 257

- ^ First published in Les Cahiers du Cinéma (Paris), July 1963. Fava and Vigano, 116

- ^ Johnson, Eric C. "Cahiers du Cinema: Top Ten Lists 1951–2009". alumnus.caltech.edu. Archived from the original on 27 March 2012. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Kezich, 247

- ^ John Simon considered the film's originality was compromised "because the 'dance of life' at the end was suggested by Bergman's dance of death in The Seventh Seal (which Fellini had not seen)". Quoted in Alpert, 181

- ^ First published in the NYT, 26 June 1963. Fava and Vigano, 118

- ^ First published in the New York Post, 26 June 1963. Fava and Vigano, 118.

- ^ a b Alpert, 181

- ^ Bondanella, The Films of Federico Fellini, 93.

- ^ Ebert,"Fellini's 8½" Archived 16 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Chicago Sun-Times (7 May 1993). Retrieved 21 December 2008.

- ^ "De bästa filmerna". Chaplin. Swedish Film Institute. November 1964. pp. 333–334.

- ^ "Take One: The First Annual Village Voice Film Critics' Poll". The Village Voice. 1999. Archived from the original on 26 August 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2006.

- ^ "Entertainment Weekly's 100 Greatest Movies of All Time". Filmsite.org. Archived from the original on 31 March 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. "8 1/2 movie review & film summary (1963) | Roger Ebert". rogerebert.com/.

- ^ "The Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll: 1972". bfi.org. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ "The Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll: 1982". bfi.org. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2021.

- ^ "Sight & Sound top 10 poll 1992". BFI. Archived from the original on 18 June 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- ^ "Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 2002 The Rest of Director's List". old.bfi.org.uk. Archived from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ "The Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 2002 The Rest of Critic's List". old.bfi.org.uk. Archived from the original on 13 August 2016. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

- ^ Schickel, Richard (13 January 2010). "8½". Time.

- ^ "Cahiers du cinéma's 100 Greatest Films". 23 November 2008.

- ^ "The 100 Best Films of World Cinema". Empire.

62. 8½

- ^ *"Wyniki ankiety: 12 filmów na 120-lecie kina". Muzeum Kinematografii w Łodzi. Archived from the original on 20 July 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- "ŚWIAT – NAJLEPSZE FILMY według wszystkich ankietowanych". Muzeum Kinematografii w Łodzi. Archived from the original on 7 October 2017. Retrieved 14 January 2017.

- "POLSKA – NAJLEPSZE FILMY według wszystkich ankietowanych". Muzeum Kinematografii w Łodzi. Archived from the original on 8 October 2017. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ^ "8 1/2". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ^ "8½". Metacritic.

- ^ "The 36th Academy Awards (1964) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: 8½". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 27 February 2009.

- ^ Alpert, 180.

- ^ "3rd Moscow International Film Festival (1963)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- ^ Kezich, 248

- ^ Kezich, 246

- ^ Kezich, 249

- ^ "Martin Scorsese's Top 10". British Film Institute.

- ^ "Martin Scorsese's Top 10". The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Kezich, 249-250

Bibliography

[edit]- Affron, Charles. 8½: Federico Fellini, Director. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1989.

- Alpert, Hollis. Fellini: A Life. New York: Paragon House, 1988.

- Bondanella, Peter. The Cinema of Federico Fellini. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.

- Bondanella, Peter. The Films of Federico Fellini. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Fava, Claudio and Aldo Vigano. The Films of Federico Fellini. New York: Citadel Press, 1990.

- Fellini, Federico. Comments on Film. Ed. Giovanni Grazzini. Trans. Joseph Henry. Fresno: The Press of California State University at Fresno, 1988.

- Kezich, Tullio. Federico Fellini: His Life and Work. New York: Faber and Faber, 2006.

External links

[edit]- 8½ at IMDb

- 8½ at AllMovie

- 8½ at Rotten Tomatoes

- 8½ at the TCM Movie Database

- Chicago Sun-Times review Archived 16 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine by Roger Ebert

- Guardian.uk review by Derek Malcolm

- 8½: A Film with Itself as Its Subject – an essay by Alexander Sesonske at The Criterion Collection

- 1963 films

- 1963 comedy-drama films

- 1960s French films

- 1960s French-language films

- 1960s Italian films

- 1960s Italian-language films

- Best Foreign Language Film Academy Award winners

- Films à clef

- Films about dreams

- Films about film directors and producers

- Films adapted into plays

- Films directed by Federico Fellini

- Films produced by Angelo Rizzoli

- Films scored by Nino Rota

- Films set in Rome

- Films shot in Rome

- Films that won the Best Costume Design Academy Award

- Films with screenplays by Federico Fellini

- French black-and-white films

- French comedy-drama films

- Italian black-and-white films

- Italian comedy-drama films

- Italian-language French films

- Self-reflexive films

- Semi-autobiographical films