257 Central Park West

| 257 Central Park West | |

|---|---|

The profile from the 86th Street transverse of Central Park | |

| |

| Former names | Orwell House, Peter Stuyvesant Hotel, Central Park View, 2 West 86th Street |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Beaux Arts |

| Location | Manhattan, NY 10024 |

| Address | 257 Central Park West |

| Country | U.S. |

| Coordinates | 40°47′06″N 73°58′11″W / 40.78500°N 73.96972°W |

| Groundbreaking | 1905 |

| Completed | 1906 |

| Owner | Private |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 12 |

| Lifts/elevators | 3 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architecture firm | Mulliken and Moeller.[note 1] |

| Main contractor | Gotham Building & Construction |

| Designations | Upper West Side-Central Park West Historic District |

257 Central Park West (also known as the Orwell House[1]) is a co-op apartment building on the southwest corner of 86th Street and Central Park West in the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. It was designed by the firm of Mulliken and Moeller[2] and built by Gotham Building & Construction between 1905 and 1906.[3]

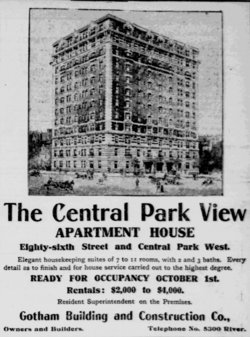

The structure was constructed as a luxury apartment house originally called the Central Park View. Mulliken and Moeller had recently finished The Lucerne,[4] on the corner of 79th and Amsterdam Avenue, and the Bretton Hall hotel[5] on the east side of Broadway from 85th to 86th Streets. When Mulliken and Moeller began working on the Central Park View in 1905 for an investor group known only as the Monticello Realty Company, they were also designing the Severn and Van Dyck apartments[6][7] (found on the east side of Amsterdam Avenue between 72nd and 73rd streets) for a separate client.[8] In the following year, Mulliken and Moeller designed Rossleigh Court, the adjoining and similarly designed apartment building located on the northwest corner of 85th Street and Central Park West. In 1909, H. F. L. Ziegel and his wife, Beatrice, added the adjoining Neo-Georgian residence at 8 West 86th Street[9]

Situated opposite the 86th Street transverse to Central Park West on the southwest corner, the Central Park View's design followed the popular "French Flat" model in a Beaux Arts-style, modified to conform to the size of a twelve-story structure. Upon its completion, the new hotel anchored the eastern end of the developing West 86th Street. On the western end of West 86th Street, the Columbia Yacht Club[10][11] had relocated to a site adjoining the Hudson River in 1874 and remained the other West 86th Street bookend until 1937.[12][13]

257 Central Park West is located within the Upper West Side-Central Park West Historic District, designated on April 24, 1990.[14] It is also located next to the 86th Street station of the New York City Subway (A, B, and C trains).

Design

[edit]Facade

[edit]Starting at the sidewalk level and moving up to the parapet, there is a simple but massive limestone base up to the windowsill at the 1st floor. From this level up to the level of the 3rd floor sill, there is a facing of limestone, with deep horizontal rusticated joints, terminating with a sill course above the 3rd floor.

From the 3rd floor up to the sill level of the 4th floor, the course and window trims and 4th floor sill course are of architectural terracotta, with an isolated alternate course of red face brick.

From this 4th floor to the sill of the 11th floor, the façade is red face brick, with isolated courses, window trims and sills of architectural terracotta with three groups of suppressed window balcony and pediment head trims on each facade of architectural terracotta, and with continuous vertical corner quoins of architectural terracotta.

The 11th floor sill course is a continuous suppressed cornice of modest projection. From this level to the 12th floor sill level, the wall treatment is essentially a repetition of the treatment between the sill levels of the 3rd and 4th floor, but with a wide, prominently projecting, and continuous sill cornice. At the 12th floor, the wall is red face brick, with quoins of architectural terracotta at the corners of the building.

The street walls are thirty-four inches thick in the cellar, twenty-six inches thick at the 1st and 2nd floors, sixteen inches thick from the 3rd to 7th floors, and twelve inches thick from the 8th floor to the parapet above the main roof.

Interior

[edit]The framing system consists of cast-iron columns carrying steel girders and steel beams, which in turn support concrete floors and the roof deck.

The columns rest upon cast-iron base-plates, which in turn rest upon masonry piers founded on the schist bedrock laying a short distance below the cellar floor level.

Continuous peripheral foundations also resting upon bedrock carry the exterior masonry walls. These walls are self-supporting and independent of the steel framing system and are tied to the steel framing at every floor level.

The floors consist of four-inch thick reinforced cinder concrete slabs. Although all floor slabs are level, the roof slab is framed with an integral slope so that it pitches downward gently from a uniformly high level at Central Park West and West 86th Street sides to a low level along the inner court sides and also downward from the south end of the west wing to a valley along the court walls.

History

[edit]Opening

[edit]The Central Park View opened in 1906, in the midst of a decade which saw New York City add a number of its iconic structures. George B. McClellan, Jr. was mayor between 1904 and 1909, and during his Tammany-backed term of office, the Williamsburg Bridge and the Manhattan Bridge, the Municipal Ferry Pier, and the first IRT subway line were all completed. The construction of Grand Central Terminal and the erection of the New York Public Library Main Branch also were ongoing during this decade and would be completed soon after.

Designed originally as a luxury apartment house,[note 2] the main entrance faced north on West 86th Street and featured an ornate entrance opening from a porte cochère and leading into the lobby.[15] From there, a central courtyard reached further into an open interior yard level providing both improved light and ventilation to the apartments above as well as privacy from the street.

The original apartments were designed for luxury,[17] arranged in seven, nine, ten and eleven-room suites, each with two or three bathrooms. Each suite included the modern amenities of telephone service, an automated mail delivery system, filtered water, storage in the basement and elevators serving all floors. The interiors were designed elegantly, with parquet floors and apartments finished in quartered oak, birch and mahogany. The kitchen contained porcelain sinks and tubs, nickel-plated plumbing, gas ranges, and five-foot marble wainscoting. The interior courtyards and the broad exterior facing offered the rooms light and air.

The custodian's apartment occupied part of the cellar and three apartments were built on the first floor. Each of the upper floors, namely the 2nd through 12th floors, was constructed with four apartments, making a total of forty-eight apartments, including the custodian's residence.

Multiple design changes

[edit]

The original design did not last long. In 1907 the developer, the Monticello Realty Company, sold the new apartment to David H. Taylor and Charles W. Odgen for $1,850,000.[note 4] Shortly thereafter in 1909 the central and south courtyards were excavated and a new single-floor roof was constructed at curb level to accommodate additional storeroom and a custodian's workroom. The building was sold again in November 1914[18] Laundry tubs and a water closet were added in the basement in 1917 but no other major renovation is recorded before 1918.

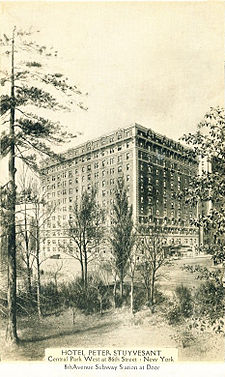

From 1918 to 1920, the building underwent its first major renovation, the conversion from luxury apartment to the Hotel Peter Stuyvesant sponsored by the Sonn Brothers and the Peter Stuyvesant Operating Company.[note 5] The Peter Stuyvesant Operating Company leased the property from the Sonn Brothers under a 21-year lease, with a net lease value of $3,000,000 – a remarkably high value for the time. The lessee, led by William F. Ingold, conducted the refurbishment of the apartments to a residence hotel, with the plans provided by the architects Schwartz & Gross and B.N. Marcus. Under the new configuration, only a single apartment resided on the first floor, with new dining rooms and a reception area replacing the other two first floor apartments along the Central Park West front of the building. The entire first floor, in Cato and Belgian black marble, was adorned with blue and gold decoration.[19] On the second through twelve floors were nineteen bedrooms, eleven living rooms, and nineteen bathrooms per level, alongside new partitioning and plumbing appropriate for hoteling use.

Other later renovations again changed the usage of the first floor space. In 1939, a cabaret and piano bar was added to the first floor. Outside the striped awnings that once adorned each window on the Central Park West facade disappeared, as did the light well still present along the building to the south. By 1950, the elevator men were gone as the cars were upgraded to new automatic versions from their prior manual operation.

This configuration lasted for nearly twenty years as the Hotel Peter Stuyvesant was operated by the Knott Hotel Corporation as a Class A hotel.[note 6] The neighborhood itself would change as the IND Eighth Avenue Line with its 5-cent fares opened in 1932[20] and replaced the uptown trolley system that once used the 86th Street transverse.[note 7] More importantly, the independent subway line tied the uptown property and those near it to the bustling metropolis forming in midtown Manhattan, only one and a half miles to the south.

The property was operated as a residential hotel up to its sale to Wilger Realty Corporation in 1941.[22] By the late 1940s and 1950s, two other renovations again would change Hotel Peter Stuyvesant's footprint. In 1949, the partitioning on the second through twelfth floors again was changed to incorporate nineteen apartments per floor. In 1957, the western dining room and the cabaret, the latter having established a poor reputation with the police, were renovated to accommodate new medical and legal office space. In 1960, the property was sold again to Soltzer & Lampert, real estate operators.[23]

In the 1960s, the notability of the building was limited, although Fred Rust and Bill Davies taught ballroom dancing in the first floor ballroom[24] until 1967. Their departure appears to coincide with another sale of the property. Stuyvesant Apartments, a partnership formed between Simon Haberman and Walter Schulze, purchased the building on April 17. 1967. The building underwent an alteration completed in 1970 replacing all internal partitions, while maintaining its external features, and including eighty-nine apartments on the upper floors (eight per floor but nine on the ninth), a group medical center on the first floor, and a garage in part of the cellar. An entrance to the lobby was added on the Central Park West side, with the former entrance on West 86th Street being retained as an entrance for the medical center.

The then-owners renamed the property as The Orwell House after the English author whom one of the sponsors enjoyed. That moniker remained until the early 2000s when the resident-shareholders decided to change the name to simply 257 Central Park West.

Co-op conversion

[edit]In 1978, Stuyvesant Apartments converted the apartments to co-operative ownership, selling most of the apartment units to the residents. The property has been owned by a private co-operative corporation for over thirty-five years. As the co-op was approaching its twenty-fifth anniversary in 2003, the co-operatives' shareholders began a series of renovations aimed at restoring its historical façade and modernizing its mechanical systems. Many of the residents and shareholders likewise have renovated their homes with designs that match the residence's elegance and location with modern conveniences.

The proximity to Central Park and the Mariner's Gate at West 85th Street positions the century-old home very close to several attractions within Central Park: the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Reservoir, the Great Lawn and Turtle Pond, the Delacorte Theater, the Shakespeare Garden, the Swedish Cottage Marionette Theatre, Bethesda Fountain, the Mariners[25] and Abraham and Joseph Spector's playgrounds[26] the Arthur Ross Pinetum, the Cleopatra's Needle, the Belvedere Castle, and the Winterdale Arch.[27] The building also sits near the historical sites of Seneca Village and the Yorkville Reservoir.[28]

In popular culture

[edit]The building has been used as a setting in several films, including:

- Fame (1980)

- Other People's Money (1991)[29]

- Music of the Heart (1999)

- Hide and Seek (2005)[30]

Notable residents

[edit]257 Central Park West has been the residence of several famous people over the years:

- Bea Arthur was an award winning American actress, comedian and activist.

- Ernest Bloch – Swiss-born American composer.[31]

- Leon Bramson – author, member of the State Duma (Russian Empire), and leader of the World ORT.[32]

- Anton Schwartz[note 8] the co-founder and President of the Bernheimer & Schwartz Pilsener Brewing Company who co-commissioned the Mink Building.

- Carrie Chapman Catt – U.S. women's suffrage leader[33] and first President of the International Women's Suffrage Alliance. Resided with Mary Garrett Hay, a temperance worker and U.S. women's suffrage leader.[34]

- Horacio Gutierrez – Cuban-American classical pianist.[35]

- Alberto Jonas – Spanish pianist and composer.[citation needed]

- Menahem Pressler – German-American pianist and founder of the Beaux Arts trio.[36][37]

- Jimmy Radcliffe – American soul singer, composer, conductor, and producer.[38]

- Max von Schillings – German conductor, composer, and theater director.[39]

- Artur Schnabel – Austrian classical pianist.[40]

- Mordecai Shehori- Israeli-American classical pianist.

- Sue Simmons – television reporter and news anchor.

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Much of the work was sponsored by James and David Todd.

- ^ For an original cost of $950,000 according to the records at the Office of Metropolitan History.

- ^ The post card reads, "The PETER STUYVESANT, an outstanding residential hotel of the upper West Side, commands a beautiful vista of Central Part at 86th Street. The hotel has large single rooms and suites designed for occupancy of those who demand space and comfort. It has an excellent a la carte dining room, where choice wines and liquors are served, and a most attractive Sidewalk Cafe."

- ^ According to a pair of articles in the New York Times, dated March 1, 1907, and August 14, 1907, the Monticello Realty Company sold the Central Park View for $1,250,000 and a building, the Chatham Court. The cash consideration was paid by Mr. David H. Taylor and the property contribution was made by Mr. Charles W. Odgen.

- ^ Hyman and Henry Sonn owned the property through the 1000 Westchester Avenue Company.

- ^ A 1935 map of the Knott Hotels lists the Hotel Peter Stuyvesant at Central Park West at 86th Street. The hotel advertises that all rooms have baths, single rooms charges $4 per night and double rooms charge $6 per night.

- ^ The New York and Harlem Railroad operated a crosstown trolley that ran east from Eighth Avenue (aka Central Park West) across the Transverse Road to York Avenue and then turned north where it terminated at the 92nd Street ferry slip.[21]

- ^ According to the 1910 U.S. Census, Schwartz lived here with his wife, his son Adolf, and two servants, until the deaths of him and his son in that same year.

References

[edit]- ^ "Orwell House, 257 Central Park West, "h" Apartment - The New York real estate brochure collection". DLC Catalog. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ Christopher Gray (September 14, 2003). "Streetscapes/Mulliken & Moeller, Architects; Upper West Side Designs in Brick and Terra Cotta – New York Times". The New York Times. New York City. Archived from the original on October 30, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Upper West Side/ Central Park West District Designation Report, Vol. I: Essay/ Architects' Appendix, April 24, 1990.

- ^ New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Upper West Side/ Central Park West District Designation Report, Vol. II: Building Entries, April 24, 1990.

- ^ "Museum of the City of New York – Broadway between 85th and 86th Streets. Bretton Hall Apartment House". Secure.collections.mcny.org. Archived from the original on November 24, 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "Severn and Van Dyck". Archived from the original on September 13, 2020. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "apartment buildings". Secure.collections.mcny.org. January 7, 1945. Archived from the original on November 24, 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (September 14, 2003). "Streetscapes/Mulliken & Moeller, Architects; Upper West Side Designs in Brick and Terra Cotta". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ tom Miller (January 9, 2014). "8 West 86th Street". Daytoninmanhattan.blogspot.com. Archived from the original on August 9, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "Museum of the City of New York – 86th Street and Hudson River. Columbia Yacht Club, general exterior from yacht on river". Secure.collections.mcny.org. Archived from the original on November 24, 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "The Columbia Yacht Club". Thehistorybox.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ [1][unreliable source?]

- ^ "Museum of the City of New York – 86th St., east from West End Ave, New York". Secure.collections.mcny.org. Archived from the original on November 24, 2013. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "Upper West Side – Central Park West Historic District". Landmarkwest.org. Archived from the original on April 15, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Offering Plan for Premises at 257 Central Park West, 1978.

- ^ "Central Park West". New-York Tribune. Chroniclingamerica.loc.gov. September 23, 1906. p. 13. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ New York Tribune, September 16, 1906, http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030214/1906-09-16/ed-1/seq-12/ Archived February 3, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The New York Sun, November 14, 1914, http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030272/1914-11-21/ed-1/seq-15/ Archived November 8, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ The New York Times, February 1, 1920.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Gay Midnight Crowd Rides First Trains in New Subway". The New York Times. September 10, 1932. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 12, 2012. Retrieved June 29, 2018.

- ^ Meyers, Stephen L. Manhattan's Lost Streetcars. Charleston, SC: Arcadia, 2005.

- ^ The New York Times, January 21, 1941.[full citation needed]

- ^ The New York Times, July 11, 1960.[full citation needed]

- ^ "The Greater New York Chapter of USA Dance". Nyusadance.org. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Central Park Conservancy. "Mariner's Playground". Centralparknyc.org. Archived from the original on March 10, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Central Park Conservancy. "Abraham and Joseph Spector's". Centralparknyc.org. Archived from the original on March 10, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Winterdale Arch[usurped].

- ^ Gray, Christopher (February 8, 2013). "Yorkville Reservoir". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved February 18, 2017.

- ^ "Other People's Money Film Locations". On the set of New York.com. July 26, 2013. Archived from the original on August 13, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "Hide And Seek: Robert De Niro, Dakota Fanning, Famke Janssen, Elisabeth Shue: Amazon Video". Amazon. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Lashier, Tricia Morgan; The Digital Diva; White Wolf Media; Michelle Harris; Newport Internet. "1930–1939 – Ernest Bloch Legacy". Ernestbloch.org. Archived from the original on May 19, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "Letter from J. C. Hyman to Dr. Leonty Bramson" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2013.

- ^ The New York Times, November 7, 1910.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Mary Garrett Hay". Nwhm.org. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "Horacio Gutierrez | Chasing Perfection Horacio Gutierrez combines superlative musicianship and technique. Maintaining the mix takes tremendous work. – Page 2 – Baltimore Sun". Articles.baltimoresun.com. February 2, 1997. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ Charles Michener (June 6, 2014). "Enduring and Preeminent: A Multigenerational Piano Trio | New York Observer". Observer.com. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "The Beaux Arts Trio News". Beauxartstrio.org. Archived from the original on July 5, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ "Jimmy Radcliffe Biography". Jimmyradcliffe.20m.com. July 27, 1973. Archived from the original on December 26, 2014. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ^ The New York Times, March 1, 1924.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Artur Schnabel: Brahms's chamber music with Szigeti and Fournier | Arbiter of Cultural Traditions". February 6, 2000. Archived from the original on July 9, 2015. Retrieved December 28, 2014.

Further reading

[edit]- A History of Housing in New York City by Richard Plunz

- Alone Together: A History of New York's Early Apartments by Elizabeth Collins Cromley

- Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America by Gwendolyn Wright

- A Guide to Researching The History Of A New York City Building

External links

[edit]Landmarking information

- Central Park West Historic District, National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, New York State Historic Preservation Office.

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission Upper West Side-Central Park West Historic District Designation Report. Vol I

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission Upper West Side-Central Park West Historic District Designation Report. Vol II

- New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission Upper West Side-Central Park West Historic District Designation Report. Vol III

Historical photos

- 1908 Photo from the Southeast

- 1919 Photo from the Northeast

- 1920 Photo from the Northeast

- 1925, Central Park West at 86th Street

- 1929 Photo from Central Park

- 1929 Looking west from Central Park West

- 1929 Peter Stuyvesant Hotel, other buildings; El in background

- 1929 Looking from the 86th Street trolley line

- 1936 Looking from the 86th Street transverse

- 1936 Photo from the 86th Street Transverse

- 1906 establishments in New York City

- Apartment buildings in New York City

- Beaux-Arts architecture in New York City

- Central Park West Historic District

- Historic district contributing properties in Manhattan

- Condominiums and housing cooperatives in Manhattan

- History of Manhattan

- Residential buildings completed in 1906

- Residential buildings in Manhattan

- Residential buildings on the National Register of Historic Places in Manhattan

- Upper West Side