Christian state

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity |

|---|

|

A Christian state is a country that recognizes a form of Christianity as its official religion and often has a state church (also called an established church),[1] which is a Christian denomination that supports the government and is supported by the government.[2]

Historically, the nations of Aksum, Armenia,[3][4] Makuria, and the Holy Roman Empire have declared themselves as Christian states, as well as the Roman Empire and its continuation the Byzantine Empire, the Russian Empire, the Spanish Empire, the British Empire, the Portuguese Empire, and the Frankish Empire, the Belgian colonial empire, the French empire.[5][6]

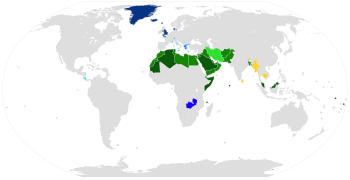

Today, several nations officially identify themselves as Christian states or have state churches. These countries include Argentina, Armenia, Costa Rica, El Salvador,[7] Denmark (incl. Greenland and the Faroes),[8] England,[9] Dominican Republic,[10] Georgia,[11] Greece,[12] Hungary,[13] Iceland,[14] Liechtenstein,[15] Malta,[16] Monaco,[17] Norway,[18] Samoa,[19] Serbia,[20] Tonga,[21] Tuvalu,[22] Vatican City,[23] and Zambia.[24] A Christian state stands in contrast to a secular state,[25] an atheist state,[26] or another religious state, such as a Jewish state,[27] or an Islamic state.[28]

History

[edit]

The Armenian Apostolic Church church puts its founding at 301, with the conversion of Tiridates and declaration of Christianity as the official state religion, although the date is disputed.[29] In 380, three Roman emperors issued the Edict of Thessalonica (Cunctos populos), making the Roman Empire a Christian state,[5] and establishing Nicene Christianity, in the form of its State Church, as its official religion.[30]

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5th century, the Eastern Roman Empire under the emperor Justinian (reigned 527–565), became the world's predominant Christian state, based on Roman law, Greek culture, and the Greek language."[6][31][32] In this Christian state, in which nearly all of its subjects upheld faith in Jesus, an "enormous amount of artistic talent was poured into the construction of churches, church ceremonies, and church decoration".[31] John Binns describes this era, writing that:[33]

A new stage in the history of the Church began when not just localised communities but nations became Christian. The stage is associated with the conversion of Constantine and the beginnings of a Christian Empire, but the Byzantine Emperor was not the first ruler to lead his people into Christianity, thus setting up the first Christian state. That honour traditionally goes to the church of Armenia.[33]

— John Binns, An Introduction to the Christian Orthodox Churches

As a Christian state, Armenia "embraced Christianity as the religion of the King, the nobles, and the people".[3] In 326, according to official tradition of the Georgian Orthodox Church, following the conversion of Mirian and Nana, the country of Georgia became a Christian state, the Emperor Constantine the Great sending clerics for baptising people. In the 4th century, in the Kingdom of Aksum, after Ezana's conversion to the faith, this empire also became a Christian state.[4][34]

In the Middle Ages, efforts were made in order to establish a Pan-Christianity state by uniting the countries within Christendom.[35][36] Christian nationalism played a role in this era in which Christians felt the impulse to also recover those territories in which Christianity historically flourished, such as the Holy Land and North Africa.[37]

The First Great Awakening, American Revolution, and Second Great Awakening caused two rounds of disestablishment among the states of the new United States, from 1776 to 1833.[38]

Modern era

[edit]

Argentina

[edit]Article 2 of the Constitution of Argentina explicitly states that "the Federal Government supports the Roman Catholic Apostolic Faith" and Article 14 guarantees freedom of religion.[39][40][41] Although it enforces neither an official nor a state faith,[42] it gives Catholic Christianity a preferential status.[43][44][45] Before its 1994 amendment, the Constitution stated that the President of the Republic must be a Roman Catholic.

Armenia

[edit]In Armenia Christianity is the state religion and the Armenian Apostolic Church is the national church. Armenia is the first country who recognised Christianity as a state religion.

Costa Rica

[edit]The constitution of Costa Rica states that "The Catholic and Apostolic Religion is the religion of the State".[7] As such, Catholic Christian holy days are recognized by the government and "public schools provide religious education", although parents are able to opt-out their children if they choose to do so.[46]

Denmark

[edit]

As early as the 11th century AD, "Denmark was considered to be a Christian state",[47][48] with the Church of Denmark, a member of the Lutheran World Federation, being the state church.[49] Prof. Wasif Shadid, of Leiden University, writes that:

The Lutheran established church is a department of the state. Church affairs are governed by a central government ministry, while clergy are government employees. The registration of births, deaths and marriages falls under this ministry of church affairs, and normally speaking the local Lutheran pastor is also the official registrar.[8]

— W. A. R. Shadid, Religious Freedom and the Position of Islam in Western Europe, page 11

Over 82% of the population of Denmark are members of the Lutheran Church of Denmark, which is "officially headed by the queen of Denmark".[50] Furthermore, clergy "in the Church of Denmark are civil servants employed by the Ministry of Ecclesiastical Affairs" and the "economic base of the Church of Denmark is state-collected church taxes combined with a direct state subsidiary (12%), which symbolically covers the expenses of the Church of Denmark to run the civil registration and the burial system for all citizens."[50]

England

[edit]

Barbara Yorke writes that the "Carolingian Renaissance heightened appreciation within England of the role of king and church in a Christian state."[51] As such,

Since the 1701 Act of Establishment, England's official state church has been the Church of England, the monarch being its supreme governor and 'defender of the faith'. He, together with Parliament, has a say in appointing bishops, twenty-six of whom have ex officio seats in the House of Lords. In characteristically British fashion, where the state is representative of civil society, it was Parliament that determined, in the Act of Establishment, that the monarch had to be Anglican.[9]

— Christian Joppke, page 1

Christian religious education is taught to children in primary and secondary schools in the United Kingdom.[52] English schools have a legal requirement for a daily act of collective worship "of a broadly Christian character"[53] that is widely flouted.[54]

Dominican Republic

[edit]The Dominican Republic is a Christian state, with Catholic Christianity being the official religion.[10] In view of the same, the government of the Dominican Republic extends special privileges to the Catholic Church.[10] National holidays include holy days of Christianity, such as the Epiphany (January 6), Good Friday, Corpus Christi, and Christmas Day. In the Dominican Republic, religious education classes must be of either a Catholic or evangelical Protestant basis and are required be taught in all elementary and secondary public schools.[10]

Faroe Islands

[edit]The Church of the Faroe Islands is the state church of Faroe Islands.[55]

Georgia

[edit]Georgia is one of the oldest Christian states. Article 8 of Georgian Constitution and the Concordat of 2002 grants the Georgian Orthodox Church special privileges, which include legal immunity to the Patriarch of Georgia. The Orthodox Church is the most trusted institution in the country[56][57] and its head, Patriarch Ilia II, the most trusted person.[58][59]

Greece

[edit]Greece is a Christian state,[12][60] with the Greek Orthodox Church playing "a dominant role in the life of the country".[61]

Mount Athos and most of the Athos peninsula are governed as an autonomous region in Greece by the monastic community of Mount Athos, which is ecclesiastically under the direct jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople.

Greenland

[edit]Being an autonomous constituent country within the Kingdom of Denmark, the Church of Denmark is the established church of Greenland through the Constitution of Denmark:

The Evangelical Lutheran Church shall be the Established Church of Denmark, and, as such, it shall be supported by the State.

— Section IV of Constitution of Denmark[62]

This applies to all of the Kingdom of Denmark, except for the Faroe Islands, as the Church of the Faroe Islands became independent in 2007.

Hungary

[edit]The preamble to the Hungarian Constitution of 2011 describes Hungary as "part of Christian Europe" and acknowledges "the role of Christianity in preserving nationhood", while Article VII provides that "the State shall cooperate with the Churches for community goals". However, the constitution also guarantees freedom of religion and separation of church and state.[13]

Iceland

[edit]

Around AD 1000, Iceland became a Christian state.[63] The Encyclopedia of Protestantism states that:

The majority of Icelanders are members of the state church. Almost all children are baptized as Lutheran and more than 90 percent are subsequently confirmed. The church conducts 75 percent of all marriages and 99 percent of all funerals. The Evangelical Lutheran Church in Iceland is a member of the Lutheran World Federation and the World Council of Churches.[14]

— J. Gordon Melton, Encyclopedia of Protestantism, page 283

All public schools have mandatory education in Christianity, although an exemption may be considered by the Minister of Education.[64]

Liechtenstein

[edit]Liechtenstein's constitution designates the Catholic Church as being the state Church of that country.[15] In public schools, per article 16 of the Constitution of Liechtenstein, religious education is given by Church authorities.[15]

Malta

[edit]

Section Two of the Constitution of Malta specifies the state's religion as being the Roman Catholic Apostolic Religion.[65][16] It holds that the "authorities of the Roman Catholic Apostolic Church have the duty to teach which principles are right and which are wrong" and that "religious teaching of the Roman Catholic Apostolic Faith shall be provided in all State schools as part of compulsory education".[65]

Monaco

[edit]Article 9 of the Constitution of Monaco describes "La religion catholique, apostolique et romaine [the catholic, apostolic and Roman religion]" as the religion of the state.[17]

Norway

[edit]

Church and state were formally separated in 2017 after a change to the constitution in 2012.[66][67] A timeline for the relationship between church and state is provided on the Norwegian Government's official website.[68]

Cole Durham and Tore Sam Lindholm, writing in 2013, stated that "For a period of one thousand years Norway has been a kingdom with a Christian state church" and that a decree went out in 1739 ordering that "Elementary schooling for all Norwegian children became mandatory, so that all Norwegians should be able to read the Bible and the Lutheran Catechism firsthand."[69] The modern Constitution of Norway stipulates that "The Church of Norway, an Evangelical-Lutheran church, will remain the Established Church of Norway and will as such be supported by the State."[70] As such, the "Norwegian constitution decrees that Lutheranism is the official religion of the State and that the King is the supreme temporal head of the Church."[71][72] The administration of the Church "is shared between the Ministry for Church, Education and Research centrally and municipal authorities locally",[71] and the Church of Norway "depends on state and local taxes".[73] The Church of Norway is responsible for the "maintenance of church buildings and cemeteries".[74] In the mid-20th century, the vast majority of Norwegians participated in the Lutheran Church. According to a 1957 description, "[o]ver 90 percent of the population are married by state church clergymen, have their children baptized and confirmed, and finally are buried with a church service."[75] However, current membership in the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Norway is much lower, standing at 65% of the population in 2021. [76]

Samoa

[edit]Samoa became a Christian state in 2017. Article 1 of the Samoan Constitution states that “Samoa is a Christian nation founded of God the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit”.[19]

Serbia

[edit]Serbia as a territory became a Christian state during the time of Constantine the Great in Christianization of Eastern Roman Empire, according to the research and discoveries of artifacts left by the Illyrians, Triballi and other kindred tribes. More research has since been made that perhaps prove the existence of Serbs living in the Balkans during Roman times in Ilyria. In the centuries that followed from the fourth- to the 12th-century, when Catholic Church was in a battleground between Serbia due the Eastern Orthodox Church, Serbia prevailed as Orthodox Christian state under his jurisdiction through Saint Sava.[77]

Serbia as modern state, defines in its constitution as a secular state with guaranteed religious freedom.[78] However, Orthodox Christians with 6,079,396 adherents comprise 84.5% of the country's population. The Serbian Orthodox Church is the largest traditional church of the country, adherents of which are overwhelmingly Serbs. The SOC directly or indirectly has cultural influence on both the decisions and positions of the state.[79][80][81]

Tonga

[edit]Tonga became a Christian state under George Tupou I in the 19th century,[21][82] with the Free Wesleyan Church, a member of the World Methodist Council, being established as the country's state Church.[83] Under the rule of George Tupou I, there was established a "rigorous constitutional clause regulating observation of the Sabbath".[21]

Tuvalu

[edit]The Church of Tuvalu, a Calvinist church in the Congregationalist tradition, is the state church of Tuvalu and was established as such in 1991.[84] The Constitution of Tuvalu identifies Tuvalu as "an independent State based on Christian principles".[22]

Vatican City

[edit]

Vatican City is a Christian state, in which the "Pope is ex officio simultaneously leader of the Catholic Church as well as Head of State and Head of the Government of the State of the Vatican City; he also possesses (de jure) absolute authority over the legislative, executive and judicial branches."[23]

Zambia

[edit]Jeroen Temperman, a professor of international law at Erasmus University Rotterdam writes that:

Zambia is officially a Christian state as well, though the legal ramifications clearly do not compare to the latter state. The Preamble of the Constitution of Zambia establishes Zambia as a Christian state without specifying "Christian" denominationally. It simply proclaims: "We, the people of Zambia...declare the Republic a Christian nation..." As far as state practice is concerned, it may be pointed out that the Government maintains relations with the Zambian Council of Churches and requires Christianity to be taught in the public school curriculum.[85]

— Jeroen Temperman, State-Religion Relationships and Human Rights Law, page 18

After "Zambia declared itself a Christian nation in 1991", "the nation's vice president urged citizens to 'have a Christian orientation in all fields, at all levels'."[24]

Established churches and former state churches

[edit]Current

[edit]| Location | Church | Denomination | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Denmark | Church of Denmark | Lutheran | |

| England | Church of England | Anglican | |

| Faroe Islands | Church of the Faroe Islands | Lutheran | Elevated from a diocese of the Church of Denmark in 2007 (the two remain in close cooperation) |

| Greece | Greek Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox[86] | The Church of Greece is recognized by the Greek Constitution as the "prevailing religion" in Greece.[86] However, this provision does not give official status to the Church of Greece, while all other religions are recognized as equal and may be practiced freely.[87] |

| Greenland | Church of Denmark | Lutheran | Under discussion to be elevated from The Diocese of Greenland in the Church of Denmark to a state church for Greenland, along-the-lines the Faroese Church took in 2007 |

| Iceland | Lutheran Evangelical Church | Lutheran | |

| Liechtenstein | Catholic Church[88] | Catholic | |

| Malta | Catholic Church | Catholic | |

| Monaco | Catholic Church | Catholic | 1999, reestablished again in 2020–present |

| Nicaragua | Catholic Church | Catholic | |

| Tuvalu | Church of Tuvalu | Reformed |

Former

[edit]National church

[edit]A number of countries have a national church which is not established (as the official religion of the nation), but is nonetheless recognised under civil law as being the country's acknowledged religious denomination. Whilst these are not Christian states, the official Christian national church is likely to have certain residual state functions in relation to state occasions and ceremonial. Examples include Scotland (Church of Scotland) and Sweden (Church of Sweden). A national church typically has a monopoly on official state recognition, although unusually Finland has two national churches (the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland and the Finnish Orthodox Church), both recognised under civil law as joint official churches of the nation.

See also

[edit]- Constitutional references to God

- Antidisestablishmentarianism

- Christian nationalism

- Christian Reconstructionism

- Christian republic

- Civil religion

- Halachic state

- History of Christian flags

- Integralism

- Islamic state

- Pan-Christianity

- Render unto Caesar

- Res publica Christiana

- Separation of church and state

- Theonomy

Notes

[edit]- ^ Brazilian Laws - the Federal Constitution - The Organization of State. V-brazil.com. Retrieved 5 May 2012. Brazil had Roman Catholicism as the state religion from the country's independence, in 1822, until the fall of the Brazilian Empire. The new Republican government passed, in 1890, Decree 119-A "Decreto 119-A".

Prohibits federal and state authorities to intervene on religion, granting freedom of religion.

(still in force), instituting the separation of church and state for the first time in Brazilian law. Positivist thinker Demétrio Nunes Ribeiro urged the new government to adopt this stance. The 1891 Constitution, the first under the Republican system of government, abolished privileges for any specific religion, reaffirming the separation of church and state. This has been the case ever since – the 1988 Constitution of Brazil, currently in force, does so in its Nineteenth Article. The Preamble to the Constitution does refer to "God's protection" over the document's promulgation, but this is not legally taken as endorsement of belief in any deity. - ^ In France the Concordat of 1801 made the Catholic, Calvinist and Lutheran churches state-sponsored religions, as well as Judaism.

- ^ In Hungary the constitutional laws of 1848 declared five established churches on equal status: the Catholic, Calvinist, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox and Unitarian Church. In 1868 the law was ratified again after the Ausgleich. In 1895 Judaism was also recognized as the sixth established church. In 1948 every distinction between the different denominations were abolished.[93][94]

- ^ In the Kingdom of Ireland the Church of Ireland was established in the Reformation.[95] The Act of Union 1800 created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland with the United Church of England and Ireland established outside Scotland. The Irish Church Act 1869 demerged and disestablished the Church of Ireland,[95] and the island was partitioned in 1922.

- ^ The Republic of Ireland's 1937 constitution prohibits an established religion.[96] Originally, it recognized the "special position" of the Catholic Church "as the guardian of the Faith professed by the great majority of the citizens", and recognized "the Church of Ireland, the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, the Methodist Church in Ireland, the Religious Society of Friends in Ireland, as well as the Jewish Congregations and the other religious denominations existing in Ireland at the date of the coming into operation of this Constitution".[97] These provisions were deleted in 1973.[98]

- ^ The Philippines was among several possessions ceded by Spain to the United States in 1898; religious freedom was subsequently guaranteed in the archipelago. This was codified in the Philippine Organic Act (1902), section 5: "... That no law shall be made respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, and that the free exercise and enjoyment of religious profession and worship, without discrimination or preference, shall forever be allowed." A similarly worded provision still exists in the present Constitution. Catholicism remains the predominant religion, wielding considerable political and cultural influence.

- ^ Article 25 of the constitution states: "1. Churches and other religious organizations shall have equal rights. 2. Public authorities in the Republic of Poland shall be impartial in matters of personal conviction". Article 114 of the Polish March Constitution of 1921 declared the Catholic Church to hold "the principal position among religious denominations equal before the law" (in reference to the idea of first among equals). The article was continued in force by article 81 of the April Constitution of 1935. The Soviet-backed PKWN Manifesto of 1944 reintroduced the March Constitution, which remained in force until it was replaced by the Small Constitution of 1947.

- ^ The Church in Wales was split from the Church of England in 1920, by Welsh Church Act 1914; at the same time becoming disestablished.

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Backhouse, Stephen (7 July 2011). Kierkegaard's Critique of Christian Nationalism. Oxford University Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780199604722.

...it is only as an established institution that the Church can fully preserve and promote Christian tradition to the nation. One cannot have a Christian state without a state Church.

- ^ Eberle, Edward J. (28 February 2013). Church and State in Western Society: Established Church, Cooperation and Separation. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 6. ISBN 9781409497806.

Under the established church approach, the government will assist the state church and likewise the church will assist the government. Religious education is mandated by law to be taught in all schools, public or private.

- ^ a b Milman, Henry Hart; Murdock, James (1887). The History of Christianity. A. C. Armstrong & Son. p. 258.

But while Persia fiercely repelled Christianity from its frontier, upon that frontier arose a Christian state. Armenia was the first country which embraced Christianity as the religion of the King, the nobles, and the people.

- ^ a b Ching, Francis D. K.; Jarzombek, Mark M.; Prakash, Vikramaditya (13 December 2010). A Global History of Architecture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 213. ISBN 9780470402573.

In the 4th century, King Ezana converted to Christianity and declared Aksum a Christian state—the first Christian state in the history of the world.

- ^ a b Ashby, Warren (4 July 2010). A Comprehensive History Of Western Ethics. Prometheus Books. p. 152. ISBN 9781615926947.

In the Edict of Thessalonica (380) he expressed the imperial "desire" that all Roman citizens should become Christians, the emperor adjudging all other madmen and ordering them to be designated as heretics,...condemned as such...to suffer divine punishment, and, therewith, the vengeance of that power, which we, by celestial authority, have assumed. There was thus created the "Christian State."

- ^ a b Frucht, Richard C. (2004). Eastern Europe. ABC-CLIO. p. 627. ISBN 9781576078006.

In contrast, the emperor Justinian (527–565) refashioned the eastern part of the Roman Empire into a strong and dynamic Byzantine Empire, which claimed Dalmatia, among other provinces. The Byzantine Empire became the world's predominant Christian state, based on Roman law, Greek culture, and the Greek language.

- ^ a b Yakobson, Alexander; Rubinstein, Amnon (2009). Israel and the Family of Nations: The Jewish Nation-state and Human Rights. Taylor & Francis. p. 215. ISBN 9780415464413.

Thus the Constitution of Costa Rica, which is considered a model of stable democracy in Latin America, states in Article 75: The Catholic and Apostolic Religion is the religion of the State, which contributes to its maintenance, without preventing the free exercise in the Republic of other forms of worship that are not opposed to universal morality or good customs.

- ^ a b Shadid, W. A. R. (1 January 1995). Religious Freedom and the Position of Islam in Western Europe. Peeters Publishers. p. 11. ISBN 9789039000656.

Denmark has declared the Evangelical Lutheran church to be that national church (par. 4 of the Constitution), which corresponds the fact that 91.5% of the population are registered members of this church. This declaration implies that the Danish State does not take a neutral stand in religious matters. Nevertheless, freedom of religion has been incorporated in the Constitution. Nielsen (1992, 77) gives a short description of the position of the minority religious communities in comparison to that of the State Church: The Lutheran established church is a department of the state. Church affairs are government by a central government ministry, and clergy are government employees. The registration of births, deaths and marriages falls under this ministry of church affairs, and normally speaking the local Lutheran pastor is also the official registrar. The other small religious communities, viz. Roman Catholics, Methodists, Baptists and Jews, have the constitutional status of 'recognised communities of faith'. ... Contrary to the minority religious communities, the Lutheran Church is fully financed by the Danish State.

- ^ a b Joppke, Christian (3 May 2013). Veil. John Wiley & Sons. p. 1. ISBN 9780745658575.

- ^ a b c d "2022 Report on International Religious Freedom: Dominican Republic". United States Department of State. Retrieved 5 January 2025.

A 1954 concordat with the Holy See designates Catholicism as the official state religion and extends special privileges to the Catholic Church not granted to other religious groups. These include the special protection of the state in the exercise of Catholic ministry, exemption of Catholic clergy from military service, permission to provide Catholic instruction in public orphanages, public funding to underwrite some church expenses, and exemption from customs duties. Nationally recognized holidays also include days that are traditionally only observed by Catholics.

- ^ Constitution of Georgia Archived 2018-06-12 at the Wayback Machine Article 9 (1 & 2) and 73 (1a1)

- ^ a b Jiang, Qing (2012). A Confucian Constitutional Order. Princeton University Press. p. 221. ISBN 9780691154602.

The features of the state affect the essence of the state, but the key term is that of historical identity, hence this chapter concentrates on historical identity as the essence of the state, though at times some of the other features will also be referred to. For instance, ancient Greece has now become an Orthodox Christian state. Ancient Persia (Iran) has now become a Muslim state, and the ancient Buddhist states of the Silk Route have also become Islamic states.

- ^ a b Hungary's Constitution of 2011. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b Melton, J. Gordon (1 January 2005). Encyclopedia of Protestantism. Infobase Publishing. p. 283. ISBN 9780816069835.

- ^ a b c Fox, Jonathan (19 May 2008). A World Survey of Religion and the State. Cambridge University Press. p. 119. ISBN 9781139472593.

Liechtenstein's constitution designates the Catholic Church as the state Church and guarantees religious freedom. Article 38 provides protection for the property rights of all religious institutions and states that "the administration of church property in the parishes shall be regulated by a specific law; the agreement of church authorities shall be sought before the law is enacted." Article 16 states that religious instruction in public schools "shall be given by church authorities."

- ^ a b "Chapter 1 – The Republic of Malta". Legal-Malta. Archived from the original on 27 August 2011. Retrieved 4 September 2011.

- ^ a b CONSTITUTION DE LA PRINCIPAUTE at the Wayback Machine (archived September 27, 2011) (French): Art. 9, Principaute De Monaco: Ministère d'Etat (archived from the original on 27 September 2011).

- ^ "The Constitution of Norway, Article 16 (English translation, published by the Norwegian Parliament)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-08. Retrieved 2015-11-29.

- ^ a b Wyeth, Grant (June 16, 2017). "Samoa Officially Becomes a Christian State". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on June 16, 2017. Retrieved June 16, 2017.

- ^ Paul Pavlovich. The History of the Serbian Orthodox Church

- ^ a b c Fodor's (12 February 1986). Fodor's South Pacific. Fodor's. ISBN 9780679013075.

As King George I of Tonga, Tupou created the "modern" Christian state with the Cross dominating its flag, and with the rigorous constitutional clause regulating observation of the Sabbath.

- ^ a b Temperman, Jeroen (2010). State-Religion Relationships and Human Rights Law. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 18. ISBN 9789004181489.

The Constitution of Tuvalu in a similar vein constitutes Tuvalu as "an independent State based on Christian principles...and Tuvaluan custom and tradition"; and also the Constitution of Vanuatu proclaims in its Preamble: "[we] HEREBY proclaim the establishment of the united and free Republic of Vanuatu founded on traditional Melanesian values, faith in God, and Christian principles..."

- ^ a b Temperman, Jeroen (2010). State-Religion Relationships and Human Rights Law. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 18. ISBN 9789004181489.

The Catholic State of Vatican City is, of course, the best contemporary example of a Christian state. The State of Vatican City, originally established by the Lateran Pacts of 1929, approximates most faithfully the ideal-typical conception of theocratic Roman Catholic state. The Pope is ex officio simultaneously leader of the Catholic Church as well as Head of State and Head of the Government of the State of the Vatican City; he also possesses (de jure) absolute authority over the legislative, executive and judicial branches. Practically all acts and policies of the Vatican City revolve around the interests of the Holy See and, apart from the members of the Pontifical Swiss Guard, virtually all inhabitants of the Vatican City are members of the clergy.

- ^ a b Jenkins, Philip (11 August 2011). The Next Christendom: The Coming of Global Christianity. Oxford University Press. p. 187. ISBN 9780199911530.

- ^ Boer, Roland (8 June 2012). Criticism of Earth: On Marx, Engels and Theology. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 168. ISBN 9789004225589.

Yet what is intriguing about this argument is that this modern secular state arises from, or is the simultaneous realisation and negation of, the Christian state.

- ^ Marx, Karl; McLellan, David (2000). Karl Marx: Selected Writings. Oxford University Press. p. 55. ISBN 9780198782650.

Indeed, it is not the so-called Christian state, that one that recognizes Christianity as its basis, as the state religion, and thus adopts an exclusive attitude to other religions, that is the perfected Christian state, but rather the atheist state, the ...

- ^ Burns, J. Patout (1 April 1996). War and Its Discontents: Pacifism and Quietism in the Abrahamic Traditions. Georgetown University Press. p. 92. ISBN 9781589018778.

The religious group is confronted by a pagan state, a Jewish state, a Christian state, an Islamic state, or a secular state.

- ^ Sjoberg, Laura (1 January 2006). Gender, Justice, and the Wars in Iraq. Lexington Books. p. 24. ISBN 9780739116104.

Just as Christian just war theory justified the actions of the Christian state, Islamic jihad theory began with the founding of the Islamic state.

- ^ Binns, John. An Introduction to the Christian Orthodox Churches. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002, p. 30. ISBN 0-521-66738-0.

- ^ Ismael, Jacqueline S.; Ismael, Tareq Y.; Perry, Glenn (5 October 2015). Government and Politics of the Contemporary Middle East. Taylor & Francis. p. 48. ISBN 9781317662822.

Theodosius did so through the 380 CE 'Edict of Thessalonica,' which established Nicene Christianity as the state church of the Roman Empire, with the Bishop of Rome as Pope.

- ^ a b Spielvogel, Jackson (1 January 2013). Western Civilization. Cengage Learning. p. 155. ISBN 9781285500195.

The Byzantine Empire was both a Greek and a Christian state. Increasingly, Latin fell into disuse as Greek became both the common and the official language of the empire. The Byzantine Empire was also built on a faith in Jesus that was shared by almost all of its citizens. An enormous amount of artistic talent was poured into the construction of churches, church ceremonies, and church decoration. Spiritual principles deeply permeated Byzantine art.

- ^ Truxillo, Charles A. (1 January 2008). Periods of World History: A Latin American Perspective. Jain Publishing Company. p. 103. ISBN 9780895818638.

The Byzantine Empire, stripped of Syria, Egypt, and North Africa, became a compact Orthodox Christian state, upholding its claim to Roman universalism and constructing an Orthodox Christian commonwealth among the Slavs of the Balkans and Russia.

- ^ a b Binns, John (4 July 2002). An Introduction to the Christian Orthodox Churches. Cambridge University Press. p. 145. ISBN 9780521667388.

- ^ Stanton, Andrea L.; Ramsamy, Edward (5 January 2012). Cultural Sociology of the Middle East, Asia, and Africa: An Encyclopedia. SAGE Publications. p. 1. ISBN 9781412981767.

Then, in the early 4th century, Ezana, Aksum's ruler, converted to Christianity and proclaimed Aksum a Christian state.

- ^ Snyder, Louis L. (1990). Encyclopedia of Nationalism. St. James Press. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-55862-101-5.

Major religions in the past, especially Christianity, have attempted to include all their adherents in a large union, but they have not been successful. Throughout most of the Middle Ages in Western Europe, attempts were made again and again to unite all the Christian world into a kind of Pan-Christianity, which would combine all Christians in a secular-religious state as a successor to the Roman Empire.

- ^ Snyder, Louis Leo (1984). Macro-nationalisms: A History of the Pan-movements. Greenwood Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-313-23191-9.

Throughout the better part of the Middle Ages, elaborate attempts were made to create what was, in effect, a Pan-Christianity, an effort to unite "all" the Western Christian world into a successor state of the Roman Empire.

- ^ Parole de l'Orient, Volume 30. Université Saint-Esprit. 2005. p. 488.

- ^ Vile, John R. "Established Churches in Early America". www.mtsu.edu. Retrieved 2023-04-25.

- ^ "Argentina's Constitution of 1853, Reinstated in 1983, with Amendments through 1994" (PDF). constituteproject.org.

- ^ "Argentina – Religión". argentina.gob.ar. Archived from the original on 8 October 2014.

- ^ Constitution of Argentina, arts. 14, 20.

- ^ Fayt 1985, p. 347; Bidart Campos 2005, p. 53.

- ^ Constitution of Argentina, art. 2.

- ^ In practice this privileged status amounts to tax-exempt school subsidies and licensing preferences for radio broadcasting frequencies.

- ^ "International Religious Freedom Report 2012 – Argentina". Washington, D. C.: US Department of State. 2012.

- ^ Merriman, Scott A. (14 July 2009). Religion and the State: An International Analysis of Roles and Relationships. ABC-CLIO. p. 148. ISBN 9781598841343.

The government as a whole treats religion well and allows missionaries to freely enter and move around the country. Only the Catholic holy days are recognized as holidays, but the state generally allows people time to celebrate their holy days if they are of another religion. The public schools provide religious education, but parents can opt their children out if they choose.

- ^ Warburg, Margit; Christoffersen, Lisbet; Petersen, Hanne; Hans Raun Iversen (28 June 2013). Religion in the 21st Century. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 85. ISBN 9781409480860.

- ^ Künker Auktion 121 - The De Wit Collection of Medieval Coins. Numismatischer Verlag Künker. p. 206.

Sweyn brought about Denmark's transition from a tribal civilisation to an early Christian state and furthermore modernised the organisation of the Christian church.

- ^ The Lutheran Standard, Volume 27. Augsburg Publishing House. 1987.

The state church of Denmark is Lutheran and a member of the Lutheran World Federation.

- ^ a b Juergensmeyer, Mark; Roof, Wade Clark (18 October 2011). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. p. 292. ISBN 9781452266565.

A majority of Danes, 82.1% (as of January 2008), are members of the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Denmark—by Section 4 of the constitution, the state church, officially headed by the queen of Denmark. Pastors in the Church of Denmark are civil servants employed by the Ministry of Ecclesiastical Affairs, which also constitutes the head of administration. The economic base of the Church of Denmark is state-collected church taxes combined with a direct state subsidiary (12%), which symbolically covers the expenses of the Church of Denmark to run the civil registration and the burial system for all citizens.

- ^ Yorke, Dr Barbara (1 November 2002). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. Routledge. p. 176. ISBN 9781134707256.

The Carolingian Renaissance heightened appreciation within England of the role of king and church in a Christian state.

- ^ Eberle, Professor Edward J (28 February 2013). Church and State in Western Society: Established Church, Cooperation and Separation. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 6. ISBN 9781409497806.

In the UK, the state church is the Church of England, a Protestant church. Under the established church approach, the government will assist the state church and likewise the church will assist the government. Religious education is mandated by law to be taught in all schools, public or private.

- ^ López-Muñiz, José Luis Martínez; Groof, Jan De; Lauwers, Gracienne (17 January 2006). Religious Education in Public Schools: Study of Comparative Law. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 163. ISBN 9781402038631.

The requirement that the collective worship be of a broadly Christian character is satisfied '...if it reflects the broad traditions of Christian belief without being distinctive of any particular Christian denomination.' Furthermore, it is expressly provided that not every act of collective worship be of a broadly Christian character: the requirement is satisfied provided that, taking any school term as a whole, the majority of acts of collective worship are broadly Christian in character.

- ^ "State schools 'ignoring assembly' despite legal requirement". The Telegraph. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2020.

- ^ "Heim | Hagstova Føroya". hagstova.fo. Retrieved 2023-04-25.

- ^ "Caucasus Barometer 2013 Georgia".

- ^ "Georgian church more trusted than parliament, president and PM together". 11 May 2018.

- ^ "Patriarch Ilia II: 'Most trusted man in Georgia' - CNN.com". www.cnn.com. Retrieved 2023-04-25.

- ^ "Civil.Ge | Politicians' Ratings in NDI-Commissioned Poll". old.civil.ge. Retrieved 2023-04-25.

- ^ Enyedi, Zsolt; Madeley, John T.S. (2 August 2004). Church and State in Contemporary Europe. Routledge. p. 119. ISBN 9781135761417.

Greece is the only Orthodox country in the EU.

- ^ Meyendorff, John (1981). The Orthodox Church: Its Past and Its Role in the World Today. St Vladimir's Seminary Press. p. 155. ISBN 9780913836811.

Greece therefore is today the only country where the Orthodox Church remains a state church and plays a dominant role in the life of the country.

- ^ "Constitution of Denmark" (PDF).

- ^ Kendrick, T. D. (15 March 2012). A History of the Vikings. Courier Corporation. p. 350. ISBN 9780486123424.

In becoming a Christian state, then, Iceland had avoided the chaos that was threatened by the secession of the Christian party from Althing and had cemented her friendship with the mother-country of Norway.

- ^ Jonathan Fox (2008). A World Survey of Religion and the State (Cambridge Studies in Social Theory, Religion and Politics). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-70758-9.

All public schools have mandatory education in Christianity. Formally, only the Minister of Education has the power to exempt students from this but individual schools usually grant informal exemptions.

- ^ a b Gozdecka, Dorota Anna (27 August 2015). Rights, Religious Pluralism and the Recognition of Difference: Off the Scales of Justice. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 9781317629801.

According to Section 2 of the Maltese Constitution from the year 1964, amended in 1994 and 1996, the state church of Malta is the Roman Catholic Church. According to the same section it is endowed with a legal right to determine moral rights and wrongs and is privileged in public education: 1. The religion of Malta is the Roman Catholic Apostolic Religion. 2. The authorities of the Roman Catholic Apostolic Church have the duty to teach which principles are right and which are wrong. Religious teaching of the Roman Catholic Apostolic Faith shall be provided in all State schools as part of compulsory education.

- ^ Anckar, Carsten (2021). Religion and Democracy: A Worldwide Comparison (2nd ed.). Routledge. p. 91.

- ^ Morland, Egil (2018). "New Relations between State and Church in Norway". European Journal of Theology. 27 (2): 162–169 – via EBSCO Connect.

- ^ Barne – og familiedepartementet (2019-01-29). "Forholdet mellom stat og kirke - en utvikling over 1000 år". Regjeringen.no.

- ^ Durham, W. Cole; Lindholm, Tore Sam; Tahzib-Lie, Bahia (11 December 2013). Facilitating Freedom of Religion or Belief. Springer. p. 778. ISBN 9789401756167.

- ^ The Constitution of Norway, Article 16 (English translation, published by the Norwegian Parliament) Archived September 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Eriksen, Tore Linné; Afrikainstitutet, Nordiska (2000). Norway and National Liberation in Southern Africa. Nordic Africa Institute. p. 271. ISBN 9789171064479.

- ^ Singh, Vikram (1 January 2008). Norway: The Champion of World Peace. Northern Book Centre. p. 81. ISBN 9788172112455.

- ^ Fahlbusch, Erwin (2003). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 796. ISBN 9780802824158.

- ^ Country Profile: Norway. The Unit. 1994. p. 9.

- ^ Flint, John T. (1957). State, church and laity in Norwegian society: a typological study of institutional change. University of Wisconsin–Madison. p. 10.

- ^ "Church of Norway". SSB. Retrieved 2023-04-25.

- ^ PART III. SERVIA.

- ^ "Article 11. Constitution of Serbia. Parlament of Serbia" (PDF).

- ^ "Cultural Atlas – Serbian Culture and Religion". January 2017.

- ^ "'The Serbian Church is Privileged in Society Today' – Balkan Insight". November 2010.

- ^ "Georgetown University . Berkley Center - Religion as a Political Vehicle: An Examination of the Influence of Orthodoxy in Serbia by Russia". November 2010.

- ^ Oliver, Douglas L. (1 January 1989). The Pacific Islands. University of Hawaii Press. p. 118. ISBN 9780824812331.

Tonga, according to its mission friends, exemplified how grace and selfless devotion to the task could transform a feuding array of heathen communities into a unified Christian state.

- ^ Bell, Daphne (26 April 2005). New to New Zealand: a guide to ethnic groups in New Zealand. Reed Books. ISBN 9780790009988.

Nearly all Tongans are Christian, and about 30 percent belong to the Free Wesleyan Church, the official state church.

- ^ Ferrari, Silvio (3 May 2015). Routledge Handbook of Law and Religion. Routledge. p. 217. ISBN 9781135045555.

Recent trends have moved in opposite directions: while the parliament of Tuvalu in 1991 approved legislation establishing the (Congregationalist) Church of Tuvalu as the State Church, at the end of 2007 Nepal's provisional parliamentary assembly voted to abolish the monarchy whose kings were popularly held to be reincarnations of the Hindu god Vishnu.

- ^ Temperman, Jeroen (2010). State-Religion Relationships and Human Rights Law. Brill Academic Publishers. p. 18. ISBN 9789004181489.

- ^ a b [1] The Constitution of Greece: Section II Relations of Church and State: Article 3, Hellenic Resources network.

- ^ [2] THE CONSTITUTION OF GREECE: PART TWO INDIVIDUAL AND SOCIAL RIGHTS: Article 13

- ^ Constitution Religion at the Wayback Machine (archived 26 March 2009) (archived from the original on 2009-03-26).

- ^ Constitution of 1991

- ^ https://www.elespectador.com/politica/dios-religion-y-la-constitucion-de-1991-article/

- ^ "The Constitution of Finland" (PDF). Ministry of Justice (Finland). Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Kirkkolaki 1054/1993" (in Finnish). Ministry of Justice (Finland). Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ Constitution of the Republic of Hungary at the Wayback Machine (archived 20 February 2008) (archived from the original on 2008-02-20)

- ^ The right of thought, the freedom of conscience and religion –Hungary.hu at the Wayback Machine (archived 23 May 2007) (archived from the original on 2007-05-23)

- ^ a b Livingstone, E. A.; Sparks, M. W. D.; Peacocke, R. W. (2013-09-12). "Ireland". The Concise Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. p. 286. ISBN 9780199659623. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ "CONSTITUTION OF IRELAND". Irish Statute Book. pp. Article 44. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ Keogh, Dermot; McCarthy, Dr. Andrew (2007-01-01). The Making of the Irish Constitution 1937: Bunreacht Na HÉireann. Mercier Press. p. 172. ISBN 9781856355612.

- ^ "Fifth Amendment of the Constitution Act, 1972". Irish Statute Book. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- ^ "Norway's church and state to divorce after almost 500 years". christiandaily.com. Archived from the original on 2018-02-20. Retrieved 2017-01-02.

- ^ "2017 - et kirkehistorisk merkeår". Den norske kirke, Kirkerådet. 2017-12-30. Retrieved 2017-01-02.

- ^ Under the 1967 Constitution, Catholicism was the state religion as stated in Article 6: "The Catholic Apostolic religion is the state religion, without prejudice to religious freedom, which is guaranteed in accordance with the provisions of this Constitution. Official relations of the republic with the Holy See shall be governed by concordats or other bilateral agreements." The 1992 Constitution, which replaced the 1967 one, establishes Paraguay as a secular state, as mentioned in section (1) of Article 24: "Freedom of religion, worship, and ideology is recognized without any restrictions other than those established in this Constitution and the law. The State has no official religion."

- ^ John D. Cushing (April 1969). "Notes on Disestablishment in Massachusetts, 1780-1833". The William and Mary Quarterly. 26 (2). Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture: 169–190. doi:10.2307/1918674. JSTOR 1918674.

- ^ The modern Church of Scotland has always disclaimed recognition as an "established" church. The Church of Scotland Act 1921 formally recognised the Kirk's independence from the state.

Sources

[edit]- Bidart Campos, Germán J. (2005). Manual de la Constitución Reformada (in Spanish). Vol. I. Buenos Aires: Ediar. ISBN 978-950-574-121-2.

- Fayt, Carlos S. (1985). Derecho Político (in Spanish). Vol. I (6th ed.). Buenos Aires: Depalma. ISBN 978-950-14-0276-6.

- Legal documents

- National Constituent Convention (22 August 1994), Constitution of the Argentine Nation, Santa Fe, archived from the original on 9 May 2004

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

External links

[edit] Media related to Christian countries at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Christian countries at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Christian state at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Christian state at Wikiquote