Ōkuninushi

| Ōkuninushi-no-Kami | |

|---|---|

God of nation-building, agriculture, medicine, and protective magic | |

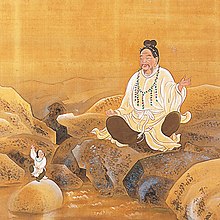

Ōkuninushi (right) and Sukunabikona (left) | |

| Other names | Ōanamuchi / Ōanamuji / Ōnamuji-no-Kami (大穴牟遅神) Ōnamuchi-no-Kami (大己貴神) |

| Japanese | 大国主神 |

| Major cult center | Izumo Taisha, Ōmiwa Shrine and others |

| Color | Black |

| Texts | Kojiki, Nihon Shoki, Izumo Fudoki and others |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Ame-no-Fuyukinu and Sashikuniwakahime (Kojiki) Susanoo-no-Mikoto and Kushinadahime (Nihon Shoki) |

| Siblings | Unnamed eighty brothers |

| Consort | Yagamihime, Suseribime, Nunakawahime,Takiribime, Kamuyatatehime, Torimimi (Totori), and others |

| Children | Kinomata (Kimata), Shitateruhime, Ajisukitakahikone, Kotoshironushi, Takeminakata and others |

Ōkuninushi (historical orthography: Ohokuninushi), also known as Ō(a)namuchi (Oho(a)namuchi) or Ō(a)namochi (Oho(a)namochi) among other variants, is a kami in Japanese mythology. He is one of the central deities in the cycle of myths recorded in the Kojiki (c. 712 CE) and the Nihon Shoki (720 CE) alongside the sun goddess Amaterasu and her brother, the wild god Susanoo, who is reckoned to be either Ōkuninushi's distant ancestor or father. In these texts, Ōkuninushi (Ōnamuchi) is portrayed as the head of the kunitsukami, the gods of the earth, and the original ruler of the terrestrial world, named Ashihara no Nakatsukuni (葦原中国, the "Central Land of Reed Plains"). When the heavenly deities (amatsukami) headed by Amaterasu demanded that he relinquish his rule over the land, Ōkuninushi agreed to their terms and withdrew into the unseen world (幽世, kakuriyo), which was given to him to rule over in exchange. Amaterasu's grandson Ninigi then came down from heaven to govern Ashihara no Nakatsukuni and eventually became the ancestor of the Japanese imperial line.

Ōkuninushi is closely associated with the province of Izumo (modern Shimane Prefecture) in western Japan; indeed, the myth of his surrender to the gods of heaven may reflect the subjugation and absorption of this area by the Yamato court based in what is now Nara Prefecture. Aside from the Kojiki and the Shoki, the imperially-commissioned gazetteer report (Fudoki) of this province dating from the early 7th century contain many myths concerning Ōkuninushi (there named 'Ōanamochi') and related deities. Myths which feature Ōkuninushi (or deities equated with him) are also found in the Fudoki of other provinces such as those of Harima (modern southwestern Hyōgo Prefecture). He is also known for his romantic escapades with a number of goddesses which resulted in many divine offspring, including the gods Kotoshironushi and Takeminakata.

He is enshrined in many Shinto shrines throughout Japan, with the Grand Shrine of Izumo (Izumo Ōyashiro / Izumo Taisha) in Shimane being the most famous and preeminent of these. The sectarian group Izumo Taishakyō based in this shrine considers Ōkuninushi as its central deity and main focus of worship. He was also syncretized with the deity Daikokuten (Mahākāla, the Buddhist version of the god Shiva) under the synthesis of Buddhism and Shinto prevalent before the Meiji period.

Name

[edit]Ōkuninushi is referred to by the following names in the Kojiki:[1][2][3]

- Ō(a)namuji-no-Kami (大穴牟遅神; historical orthography: おほ(あ)なむぢ Oho(a)namuji; Old Japanese: Opo(a)namudi) – The god's original name[3]

- Ashihara-Shikoo (葦原色許男, "Ugly Man / Young Warrior[4] of the Reed Plains"; hist. orthography: あしはらしこを; OJ: Asipara-Siko2wo) – Used in three instances in the narrative proper[5]

- Ōkuninushi-no-Kami (大国主神, "Master of the Great Land" / "Great Master of the Land"; hist. orthography: おほくにぬし Ohokuninushi; OJ: Opokuninusi) – One of two new names later given to Ōnamuji by Susanoo; used as the god's default name in the subsequent narrative[6]

- Utsushikunitama-no-Kami (宇都志国玉神, "Spirit (tama) of the Living Land" / "Living Spirit of the Land"; OJ: Utusikunitama) – Another name bestowed by Susanoo[6]

- Yachihoko-no-Kami (八千矛神, "Eight Thousand Spears"; OJ: Yatipoko2) – Used exclusively in the story of Ōkuninushi wooing Nunakawahime of Koshi[7]

- Izumo-no-Ōkami (出雲大神, "Great Deity of Izumo"; hist. orthography: いづものおほかみ, OJ: Idumo1-no2-Opokami2) – Used in an anecdote in the annals of Emperor Suinin[8]

In the Nihon Shoki, the god is mainly referred to as Ō(a)namuchi-no-Kami (大己貴神; hist. orthography: おほ(あ)なむち Oho(a)namuchi; OJ: Opo(a)namuti) or Ō(a)namuchi-no-Mikoto (大己貴命). One variant cited in the text lists the same alternate names for Ōkuninushi as those found in the Kojiki, most of which are written using different characters.[9][10]

- Ōkuninushi-no-Kami (大国主神)

- Ōmononushi-no-Kami (大物主神 "Great Thing-Master" or "Great Spirit-Master"; hist. orthography: おほのもぬし Ohomononushi; OJ: Opomo2no2nusi) – Originally an epithet for the deity of Mount Miwa in Nara Prefecture. While seemingly portrayed as a distinct entity in the Kojiki, the Shoki depicts the two as essentially being the same entity, with Ōmononushi being Ōkuninushi's aspect or spirit ( mitama)

- Kunitsukuri Ōnamuchi-no-Mikoto (国作大己貴命, "Maker of the Land, Ōnamuchi-no-Mikoto")

- Ashihara-Shikoo (葦原醜男)

- Yachihoko-no-Kami (八千戈神)

- Ōkunitama-no-Kami (大国玉神, "Spirit of the Great Land" / "Great Spirit of the Land"; hist. orthography: おほくにたま Ohokunitama; OJ: Opokunitama)

- Utsushikunitama-no-Kami (顕国玉神)

The name Ō(a)namuchi or Ō(a)namochi is also used in other texts. The Fudoki of Izumo Province, for instance, refers to the god both as Ōanamochi-no-Mikoto (大穴持命) and as Ame-no-Shita-Tsukurashishi-Ōkami (所造天下大神, "Great Deity, Maker of All Under Heaven").[11][12][13][14] The Fudoki of Harima Province meanwhile uses Ōnamuchi-no-Mikoto (大汝命); a god found in this text known as Iwa-no-Ōkami (伊和大神, "Great Deity of Iwa") is also identified with Ōkuninushi.[15]

As the first two characters of 'Ōkuninushi', 大国, can also be read as 'Daikoku', the god was conflated with the Buddhist divinity Daikokuten (Mahākāla) and came to be popularly referred to as Daikoku-sama (大黒様, だいこくさま).[16]

Genealogy

[edit]In the Kojiki, Ōnamuji / Ōkuninushi is the son of the god Ame-no-Fuyukinu (天之冬衣神) and his wife, Sashikuniwakahime (刺国若比売). The text thus portrays him as a sixth-generation descendant of the god Susanoo.[17][18]

- Pink is female.

- Blue is male.

- Grey means other or unknown.

- Clans, families, people groups are in green.

The Nihon Shoki's main narrative meanwhile depicts him as the offspring of Susanoo and Kushinadahime,[59] although a variant cited in the same text describes Ōnamuchi as Susanoo's descendant in the sixth generation (in agreement with the Kojiki).[60]

Mythology

[edit]In the Kojiki

[edit]The White Hare of Inaba

[edit]

Ōkuninushi (as Ōnamuji) first appears in the Kojiki in the famous tale of the Hare of Inaba. Ōnamuji's elder brothers, collectively known as the yasokami (八十神 'eighty deities', 'eighty' probably being an expression meaning 'many'), were all suitors seeking the hand of Yagamihime (八上比売) of the land of Inaba in marriage. As they were travelling together from their home country of Izumo to Inaba to court her, the brothers encounter a rabbit, flayed and raw-skinned, lying in agony upon the Cape of Keta (気多前 Keta no saki, identified with Hakuto Coast in Tottori Prefecture[61]). Ōnamuji's brothers, as a prank, instructed the hare to wash itself in the briny sea and then blow itself dry in the wind, but this only made the hare's pain worse.

Ōnamuji, acting as his brothers' bag-carrier, then finds the hare. Upon being asked what happened, the hare explains that it came from the island of Oki across the sea and tricked a number of wani (和邇, the term may mean either 'shark' or 'crocodile') into forming a bridge for it to cross. But before the hare had completely gotten ashore to safety, it gloated about having tricked them; in retaliation, the last wani in line then grabbed it and tore off its fur. Ōnamuji then advised the hare to wash itself in fresh water and then roll in the pollen of cattail grass. Upon doing so, the hare recovered from its injuries. In gratitude, it predicts that Ōnamuji will be the one to win the princess. [62][63][64]

This rabbit said to Ōnamuji-no-Kami:

"These eighty deities will certainly never gain Yagamihime. Although you carry their bags, you shall gain her."

At this time Yagamihime replied to the eighty deities:

"I will not accept your offers. I will wed Ōnamuji-no-Kami."[65]

Attempts on Ōnamuji's life

[edit]Ōnamuji's brothers, furious at having been rejected by Yagamihime, then conspired to slay him. They first bring Ōnamuji to the foot of Mount Tema in the land of Hōki and compelled him, on pain of death, to catch a red boar (in reality a boulder heated red-hot and rolled down the mountain by them). Ōnamuji was burned to death upon grabbing the rock, but his mother, Sashikuniwakahime, went up to heaven and petitioned the primordial deity Kamimusubi for aid. Kamimusubi dispatched two clam goddesses, Kisagaihime (𧏛貝比売) and Umugihime (蛤貝比売), who then restored Ōnamuji to life as a handsome young man.

The brothers next tricked Ōnamuji into walking onto a fresh tree log split open and held apart by a wedge, and snapped it shut, killing him a second time. His mother revived him once again and bade him to seek refuge with the god Ōyabiko-no-Kami (大屋毘古神) in the land of Ki. Ōnamuji's brothers caught up with him as he was escaping, but he eluded their grasp by slipping through a fork of a tree.[66][67]

Ōnamuji and Suseribime

[edit]

In Ki, Ōnamuji was told to seek out Susanoo, who dwelt in the subterranean realm of Ne-no-Katasu-Kuni (根堅洲国), the "Land of Roots", to obtain wise counsel. There he met Susanoo's daughter Suseribime (須勢理毘売), with whom he shortly fell in love. Upon learning of their affair, Susanoo imposed four trials on Ōnamuji:

- Susanoo first invited Ōnamuji to his palace and had him sleep in a room full of snakes. Suseribime aided Ōnamuji by giving him a magical scarf which protected him.

- The following night, Susanoo had Ōnamuji sleep in another room full of centipedes and bees. Suseribime again gave Ōnamuji a scarf that repelled the insects.

- Susanoo shot an arrow into an enormous meadow and had Ōnamuji fetch it. As Ōnamuji was busy looking for the arrow, Susanoo set the field on fire. A field mouse showed Ōnamuji a hole that he could hide in and also brought him the arrow.

- Susanoo, upon discovering that Ōnamuji had survived, summoned him back to his palace and had him pick the lice and centipedes from his hair. Using a mixture of red clay and nuts given to him by Suseribime, Ōnamuji pretended to chew and spit out the insects he was picking.

After Susanoo was lulled to sleep, Ōkuninushi tied Susanoo's hair to the rafters of the palace and fled with Suseribime, also taking Susanoo's bow and arrows and koto with him. When the couple made their escape, the koto brushed against a tree, awakening Susanoo. The god jumped up and brought down his palace around him. Susanoo then pursued them as far as the slopes of Yomotsu Hirasaka (黄泉比良, the "Flat Slope of Yomi"), the borders of the underworld. As the two were fleeing, Susanoo grudgingly gave his blessing to Ōnamuji, renaming him Ōkuninushi-no-Kami (大国主神, "Master of the Great Land") and Utsushikunitama-no-Kami (宇都志国玉神 'Spirit of the Living Land'). Using Susanoo's weapons, Ōkuninushi defeats his wicked brothers and becomes the undisputed ruler of the terrestrial realm, Ashihara no Nakatsukuni (葦原中国, the "Central Land of Reed Plains").[68][69]

Ōkuninushi's affairs

[edit]Ōkuninushi begins the monumental task of creating and pacifying Ashihara no Nakatsukuni. In accordance with their previous betrothal, he marries Yagamihime and brings her to his palace, but she, fearing Suseribime (who had become Ōkuninushi's chief wife), eventually went back to Inaba, leaving her newborn child wedged in the fork of a tree. The child was thus named 'Ki(no)mata-no-Kami' (木俣神, from ki (no) mata "tree fork").[70][69]

Ōkuninushi – in this section of the narrative given the name Yachihoko-no-Kami (八千矛神, "Deity of Eight Thousand Spears") – then wooed a third woman, Nunakawahime (沼河比売) of the land of Koshi, singing the following poem:

The god

Yachihoko,

Unable to find a wife

In the land of the eight islands,

Hearing that

In the far-away

Land of Koshi

There was a wise maiden,

Hearing that

There was a fair maiden,

Set out

To woo her,

Went out

To win her.

Not even untying

The cord of my sword,

Not even untying

My cloak,

I stood there

And pulled and shoved

On the wooden door

Where the maiden slept.

Then, on the verdant mountains,

The nue bird sang.

The bird of the field,

The pheasant resounded.

The bird of the yard,

The cock crowed.

Ah how hateful

These birds for crying!

Would that I could make them

Stop their accursed singing! [. . .][71]

Nunakawahime answers him with another song, which goes in part:

O deity

Yachihoko!

Since I am but a woman,

Supple like the pliant grass,

My heart is fluttering

Like the birds of the seashore.

Although now I may be

A free, selfish bird of my own;

Later, I shall be yours,

A bird ready to submit to your will.

Therefore, my lord, be patient;

Do not perish with yearning.[72]

Upon learning of her husband's dalliance with Nunakawahime, Suseribime became extremely jealous. Feeling harassed, Ōkuninushi prepares to leave Izumo for Yamato. Suseribime then offers Ōkuninushi a cup filled with sake, begging him (also via song) to stay with her. Ōkuninushi and Suseribime were thus reconciled.[7][73]

In addition to these three goddesses, Ōkuninushi also took three other wives and had children by them: Takiribime-no-Mikoto (多紀理毘売命), one of three goddesses born when Susanoo and Amaterasu held a ritual pact (ukehi) to prove Susanoo's innocence long ago, Kamuyatatehime-no-Mikoto (神屋楯比売命), and Torimimi-no-Kami (鳥耳神), also known as Totori-no-Kami (鳥取神).[74][75]

Ōkuninushi, Sukunabikona and Ōmononushi

[edit]When Ōkuninushi was at the Cape of Miho in Izumo, a tiny god riding on the waves of the sea in a bean-pod appears and comes to him. Ōkuninushi asked the stranger his name, but he would not reply. A toad then told Ōkuninushi to ask Kuebiko (久延毘古), a god in the form of a scarecrow who "knows all things under the heavens." Kuebiko identifies the dwarf as Sukunabikona-no-Kami (少名毘古那神), a son of Kamimusubi. At Kamimusubi's command, Ōkuninushi formed and developed the lands with Sukunabikona at his side. Eventually, however, Sukunabikona crossed over to the "eternal land" (常世国, tokoyo no kuni) beyond the seas, leaving Ōkuninushi without a partner.[76] As Ōkuninushi lamented the loss of his companion, another god appears, promising to aid Ōkuninushi in his task if he will worship him. Ōkuninushi then enshrined the deity – identified in a later narrative as Ōmononushi-no-Kami (大物主神) – in Mount Mimoro in Yamato in accordance with the latter's wish.[77][78]

The transfer of the land (Kuni-yuzuri)

[edit]After a time, the gods of Takamagahara, the 'High Plain of Heaven', declare that Ōkuninushi's realm, Ashihara no Nakatsukuni, must be turned over to their rule. Amaterasu decrees that Ame-no-Oshihomimi-no-Mikoto (天忍穂耳命), one of five male deities born during Amaterasu's and Susanoo's ukehi ritual that Amaterasu subsequently adopted as her sons, shall take possession of the land, but Ame-no-Oshihomimi, after inspecting the earth below and deeming to be in an uproar, refuses to go. A second son, Ame no hohi (天菩比命) was then sent, but ended up currying favor with Ōkuninushi and did not report for three years.[79] The third messenger, Ame-no-Wakahiko (天若日子), ended up marrying Shitateruhime (下照比売), Ōkuninushi's daughter with Takiribime. After he did not send word back for eight years, the heavenly deities sent a pheasant to question Ame-no-Wakahiko, which he killed with his bow and arrow. The bloodied arrow, after it flew up to heaven, was thrown back to earth, killing Ame-no-Wakahiko in his sleep. During Ame-no-Wakahiko's funeral, Shitateruhime's brother and Ame-no-Wakahiko's close friend Ajisukitakahikone (阿遅志貴高日子根) is furious at being mistaken for the dead god (whom he resembled in appearance) and destroys the mourning house where the funeral was held.[80][81]

The heavenly deities then dispatch the warrior god Takemikazuchi-no-Kami (建御雷神), who descends on the shores of Inasa (伊那佐之小浜 Inasa no ohama) in Izumo. Ōkuninushi tells Takemikazuchi to confer with his son Kotoshironushi-no-Kami (事代主神), his son with Kamuyatatehime, who had gone hunting and fishing in the Cape of Miho. After being questioned, Kotoshironushi accepts the demands of the heavenly kami and disappears. When Takemikazuchi asks if Ōkuninushi has any other sons who ought to be consulted, another son, Takeminakata-no-Kami (建御名方神), appears and challenges Takemikazuchi to a test of strength. Takemikazuchi defeats Takeminakata, who flees to the sea of Suwa in the land of Shinano and surrenders. After hearing that his two sons have submitted, Ōkuninushi relinquishes his control of the land. Making a final request that a magnificent palace – rooted in the earth and reaching up to heaven – be built in his honor, he withdrew himself into the "less-than-one-hundred eighty-road-bendings" (百不足八十坰手 momotarazu yasokumade, i.e. the unseen world of the spirit) and disappeared from the physical realm.[82][83]

Prince Homuchiwake

[edit]

Ōkuninushi indirectly appears in a narrative set during the reign of Emperor Suinin.

Prince Homuchiwake (本牟智和気命), Suinin's son with his first chief wife Sahohime (狭穂姫命, also Sawajihime), was born mute, unable to speak "[even when his] beard eight hands long extended down over his chest" until he heard the cry of a swan (or a crane), at which he babbled his first words. A servant named Yamanobe no Ōtaka (山辺大鶙) was dispatched to seize the bird, which he pursued across long distances until he finally caught it in the river-mouth of Wanami (和那美之水門 Wanami no minato) in Koshi. The captured bird was brought before Homuchiwake, but the prince was still unable to talk freely. In a dream, Suinin heard a god demanding that his shrine "be built like the emperor's palace," at which the prince will gain the power of speech. The emperor then performed divination (futomani), which revealed Homuchiwake's condition to have been due to a curse (tatari) laid by the "great deity of Izumo" (出雲大神 Izumo-no-Ōkami, i.e. Ōkuninushi). Suinin then bade his son to worship at the god's shrine. After going to Izumo, Homuchiwake and his entourage stopped by the Hi River (known today as the Hii River), where a pontoon bridge and a temporary dwelling was built for the prince. Homuchiwake, upon seeing a mountain-like enclosure made of leaves being set up on the river, was finally cured of his muteness and spoke coherently.[8][84]

When they were about to present his food, the prince spoke:

"That down river which is like a mountain of green leaves, looks like a mountain but is not a mountain. Could it be the ceremonial place of the priests who worship Ashihara-Shikoo-no-Ōkami in the shrine of So at Iwakuma in Izumo?"

[Thus] he inquired.

Then the princes, his attendants, heard and rejoiced, saw and were glad, and causing the prince to remain in [the place] Ajimasa-no-Nagaho-no-Miya, they sent urgent messengers [to the emperor].[85]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Saeki, Tsunemaro, ed. (1929). Kojiki (古事記). Kokumin Tosho. pp. 62–63.

- ^ Takeda, Yūkichi, ed. (1956). "Kōchū Kojiki (校註 古事記)". 青空文庫 Aozora Bunko. Retrieved 2020-05-16.

- ^ a b Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-1-4008-7800-0.

- ^ Palmer, Edwina (2015). Harima Fudoki: A Record of Ancient Japan Reinterpreted, Translated, Annotated, and with Commentary. Brill. p. 159, footnote 21. ISBN 9789004269378.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 98, 116, 222.

- ^ a b Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-4008-7800-0.

- ^ a b Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 104–112.

- ^ a b Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 219–222.

- ^ Kuroita, Katsumi (1943). Kundoku Nihon Shoki, vol. 1 (訓読日本書紀 上巻). Iwanami Shoten. p. 75.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Aoki, Michiko Y. (1997). Records of Wind and Earth: a Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Association for Asian Studies. p. 18.

- ^ Aston, William George (1905). Shinto (The Way of the Gods). Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 144.

- ^ "出雲大社と大国主大神". Izumo Ōyashiro (Izumo Taisha) Official Website. Retrieved 2021-07-18.

- ^ "オオクニヌシの物語". 編纂1300年を迎えた【古事記の神話】. Shimane Prefecture. Retrieved 2021-07-18.

- ^ Palmer (2015). pp. 21-25.

- ^ Roberts, Jeremy (2009). Japanese Mythology A to Z. Infobase Publishing. pp. 28, 92. ISBN 978-1-4381-2802-3.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. p. 92.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XX.—The August Ancestors of the Deity-Master-Of-The-Great Land.

- ^ Kaoru, Nakayama (7 May 2005). "Ōyamatsumi". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ a b c Chamberlain (1882). Section XIX.—The Palace of Suga.

- ^ a b c Chamberlain (1882). Section XX.—The August Ancestors of the Deity-Master-of-the-Great-Land.

- ^ Atsushi, Kadoya (10 May 2005). "Susanoo". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ "Susanoo | Description & Mythology". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Herbert, J. (2010). Shinto: At the Fountainhead of Japan. Routledge Library Editions: Japan. Taylor & Francis. p. 402. ISBN 978-1-136-90376-2. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ a b 大年神 [Ōtoshi-no-kami] (in Japanese). Kotobank. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ a b 大年神 [Ōtoshi-no-kami] (in Japanese). Kokugakuin University. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023. Retrieved 5 May 2023.

- ^ a b Mori, Mizue. "Yashimajinumi". Kokugakuin University Encyclopedia of Shinto.

- ^ Frédéric, L.; Louis-Frédéric; Roth, K. (2005). Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard University Press reference library. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ a b c "My Shinto: Personal Descriptions of Japanese Religion and Culture". www2.kokugakuin.ac.jp. Retrieved 2023-10-16.

- ^ “‘My Own Inari’: Personalization of the Deity in Inari Worship.” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 23, no. 1/2 (1996): 87-88

- ^ "Ōtoshi | 國學院大學デジタルミュージアム". 2022-08-17. Archived from the original on 2022-08-17. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- ^ "Encyclopedia of Shinto - Home : Kami in Classic Texts : Kushinadahime". eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp.

- ^ "Kagutsuchi". World History Encyclopedia.

- ^ Ashkenazi, M. (2003). Handbook of Japanese Mythology. Handbooks of world mythology. ABC-CLIO. p. 213. ISBN 978-1-57607-467-1. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ Chamberlain, B.H. (2012). Kojiki: Records of Ancient Matters. Tuttle Classics. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4629-0511-9. Retrieved 2020-11-21.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. p. 92.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XX.—The August Ancestors of the Deity-Master-Of-The-Great Land.

- ^ a b Ponsonby-Fane, R. A. B. (2014-06-03). Studies In Shinto & Shrines. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-89294-3.

- ^ a b "Encyclopedia of Shinto - Home : Kami in Classic Texts : Futodama". eos.kokugakuin.ac.jp. Retrieved 2021-07-13.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 104–112.

- ^ Atsushi, Kadoya; Tatsuya, Yumiyama (20 October 2005). "Ōkuninushi". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ Atsushi, Kadoya (21 April 2005). "Ōnamuchi". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ a b The Emperor's Clans: The Way of the Descendants, Aogaki Publishing, 2018.

- ^ a b c Varley, H. Paul. (1980). Jinnō Shōtōki: A Chronicle of Gods and Sovereigns. Columbia University Press. p. 89. ISBN 9780231049405.

- ^ Atsushi, Kadoya (28 April 2005). "Kotoshironushi". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ Sendai Kuji Hongi, Book 4 (先代舊事本紀 巻第四), in Keizai Zasshisha, ed. (1898). Kokushi-taikei, vol. 7 (国史大系 第7巻). Keizai Zasshisha. pp. 243–244.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XXIV.—The Wooing of the Deity-of-Eight-Thousand-Spears.

- ^ Tanigawa Ken'ichi 『日本の神々 神社と聖地 7 山陰』(新装復刊) 2000年 白水社 ISBN 978-4-560-02507-9

- ^ a b Kazuhiko, Nishioka (26 April 2005). "Isukeyorihime". Encyclopedia of Shinto. Archived from the original on 2023-03-21. Retrieved 2010-09-29.

- ^ a b 『神話の中のヒメたち もうひとつの古事記』p94-97「初代皇后は「神の御子」」

- ^ a b c 日本人名大辞典+Plus, デジタル版. "日子八井命とは". コトバンク (in Japanese). Retrieved 2022-06-01.

- ^ a b c ANDASSOVA, Maral (2019). "Emperor Jinmu in the Kojiki". Japan Review (32): 5–16. ISSN 0915-0986. JSTOR 26652947.

- ^ a b c "Visit Kusakabeyoshimi Shrine on your trip to Takamori-machi or Japan". trips.klarna.com. Retrieved 2023-03-04.

- ^ 『図説 歴代天皇紀』p42-43「綏靖天皇」

- ^ Anston, p. 143 (Vol. 1)

- ^ Grapard, Allan G. (2023-04-28). The Protocol of the Gods: A Study of the Kasuga Cult in Japanese History. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91036-2.

- ^ Tenri Journal of Religion. Tenri University Press. 1968.

- ^ Takano, Tomoaki; Uchimura, Hiroaki (2006). History and Festivals of the Aso Shrine. Aso Shrine, Ichinomiya, Aso City.: Aso Shrine.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ Aston, William George (1896). . Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. p. – via Wikisource.

- ^ "Hakuto Kaigan Coast". San'in Kaigan UNESCO Global Geopark. San'in Kaigan Geopark Promotion Council. Retrieved 2020-05-13.

- ^ Takeda 1977, p.42- (old Japanese); p.227- (modern Japanese)

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 93–95.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XVIII.—The White Hare of Inaba.

- ^ Translation from Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 89–90. Names (transcribed in Old Japanese in the original) have been changed into their modern equivalents.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 96–97.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). SECT. XXII.—Mount Tema.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 98–103.

- ^ a b Chamberlain (1882). SECT. XXIII.—The Nether-Distant-Land.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. p. 103.

- ^ Translation from Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 104–105. Names (transcribed in Old Japanese in the original) have been changed into their modern equivalents.

- ^ Translation from Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 106–107. Names (transcribed in Old Japanese in the original) have been changed into their modern equivalents.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). SECT. XXV.—The Cup-Pledge.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 113–114.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XXVI.—The Deities the August Descendants of the Deity Master-of-the-Great-Land

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XXVII.—The Little-Prince-the-Renowned-Deity.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 115–117.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XXVIII.—The August-Luck-Spirit-the-August-Wondrous-Spirit

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XXX.—The August Deliberation for Pacifying the Land.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 120–128.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XXXI.—The Heavenly-Young-Prince.

- ^ Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. pp. 129–136.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section XXXII.—Abdication of the Deity Master-of-the-Great-Land.

- ^ Chamberlain (1882). Section LXXII.—Emperor Sui-nin (Part IV.—The Dumb Prince Homu-chi-wake)

- ^ Translation from Philippi, Donald L. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. p. 222. Names (transcribed in Old Japanese in the original) have been changed into their modern equivalents.

Bibliography

[edit]- Aoki, Michiko Y., tr. (1997). Records of Wind and Earth: A Translation of Fudoki, with Introduction and Commentaries. Association for Asian Studies, Inc. ISBN 978-0924304323.

- Aston, William George, tr. (1896). Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Chamberlain, Basil, tr. (1882). A Translation of the "Ko-Ji-Ki," or "Records of Ancient Matters". Yokohama: Lane, Crawford & Co.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kuroita, Katsumi (1943). Kundoku Nihon Shoki, vol. 1 (訓読日本書紀 上巻). Iwanami Shoten.

- Philippi, Donald L., tr. (2015). Kojiki. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1400878000.

- Takeda, Yūkichi, ed. (1956). "Kōchū Kojiki (校註 古事記)". 青空文庫 Aozora Bunko. Retrieved 2020-05-16.

External links

[edit]- Official website of Izumo Ōyashiro (Izumo Taisha) (in Japanese)