1 Wall Street Court

| 1 Wall Street Court | |

|---|---|

Looking west from Wall Street | |

| |

| Former names |

|

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Type | Residential |

| Architectural style | Renaissance |

| Classification | Condominiums |

| Location | Financial District (Manhattan) |

| Address | 82–92 Beaver Street (at Pearl Street) |

| Town or city | New York City |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 40°42′19″N 74°00′30″W / 40.70528°N 74.00833°W |

| Construction started | June 1903 |

| Completed | October 1904 |

| Renovated | 2006 |

| Cost | $600,000 (1904) equivalent to $20,346,667 in 2023 |

| Height | |

| Roof | 205 feet (62 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 15 |

| Lifts/elevators | 4 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architecture firm | Clinton and Russell |

| Known for | Former headquarters of the New York Cocoa Exchange |

Beaver Building | |

New York City Landmark No. 1942

| |

| Part of | Wall Street Historic District (ID07000063[2]) |

| NRHP reference No. | 05000668[1] |

| NYCL No. | 1942 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | July 6, 2005[1] |

| Designated CP | February 20, 2007 |

| Designated NYCL | February 13, 1995[3] |

| References | |

| [4] | |

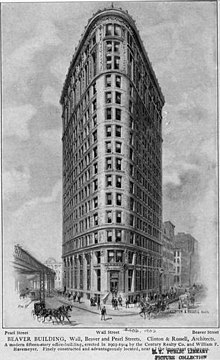

1 Wall Street Court (also known as the Beaver Building and the Cocoa Exchange) is a residential building in the Financial District of Manhattan in New York City, New York. The 15-story building, designed by Clinton and Russell in the Renaissance Revival style, was completed in 1904 at the intersection of Wall, Pearl, and Beaver Streets.

The building is shaped similarly to a flatiron because of its position at an acute angle formed by the junction of Pearl and Beaver Streets. 1 Wall Street Court's articulation consists of three horizontal sections similar to the components of a column, namely a base, shaft, and capital. The base is faced with stone, the shaft contains alternating bands of buff and tan brick, and the capital contains multicolored terracotta ornamentation depicting geometric shapes. There are carved beavers over the main entrance facing Pearl and Beaver Streets, signifying the building's original name. The superstructure is of steel frame construction.

The Beaver Building was constructed between 1903 and 1904 as a speculative development. The building served as the headquarters of the Munson Steamship Line from 1904 until 1921, and the company owned 1 Wall Street Court from 1919 to 1937. The building was foreclosed upon in 1937, and ownership subsequently passed to several other entities, including the Bowery Savings Bank. The New York Cocoa Exchange was another large tenant, occupying the building between 1931 and 1972. The commercial spaces on ground level, as well as the interior offices, were significantly altered from their original design, with major renovations in 1937 and the mid-1980s. 1 Wall Street Court was converted into a residential condominium building in 2006.

The building was designated a city landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1995 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in 2005. It is also a contributing property to the Wall Street Historic District, a NRHP district created in 2007.

Site

[edit]1 Wall Street Court is in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan. It occupies most of the block bounded by Hanover Street to the west, Pearl Street to the southeast, and Beaver Street to the north, with facades on Pearl and Beaver Streets. The building faces eastward toward the five-pointed intersection of Pearl, Beaver, and Wall Streets. It is near 55 Wall Street and 20 Exchange Place to the northwest, 63 Wall Street to the north, and 75 Wall Street to the east.[5] The property measures 122 feet (37 m) on Beaver Street, 136 feet (41 m) on Pearl Street, 20 feet (6.1 m) on the intersection with Wall Street, and 88 feet (27 m) on the west.[6][7] The plot covers 9,300 square feet (860 m2).[8] Including a four-story annex at 80 Beaver Street, it measures 140 feet (43 m) on Beaver Street and 157 feet (48 m) on Pearl Street.[9]

The narrow lot was a result of the Financial District's street grid, as outlined in the Castello Plan, a street map for the Dutch colony of New Amsterdam.[10] The site was historically part of the estate of pirate William Kidd.[11] Nearby buildings include the Wall and Hanover Building to the north and 20 Exchange Place to the northwest.[5]

Architecture

[edit]1 Wall Street Court was designed by Clinton and Russell in the Renaissance Revival style.[4][10][12] It is 205 feet (62 m) tall with 15 stories[4] and a partially raised basement.[13][14] 1 Wall Street Court is one of a few buildings in Lower Manhattan that are shaped like a flatiron, but its design was largely overlooked in favor of other buildings such as the Flatiron Building at 23rd Street.[15][16]

Facade

[edit]1 Wall Street Court's articulation consists of three horizontal sections similar to the components of a column, namely a base, shaft, and capital.[17] The two principal elevations on Pearl and Beaver Streets are joined by a rounded corner on Wall Street.[18] The windows on each side are arranged into bays, with six each on Pearl and Beaver Streets and three on the rounded corner. These bays generally have one window per floor on the first and second stories, and two windows per floor above; on two of the corner bays, there is one window per floor on the first through twelfth stories, and two windows per floor above.[19] The western facade, treated as the rear of the building, is a plain brick wall with windows.[20] There was a fire escape on the Pearl Street side, dating from 1916, but was removed in the early 21st century.[14][18]

The three-story base is faced with ashlar of granite and Indiana limestone.[7][13][14] At the main corner, facing the intersection of Beaver, Wall, and Pearl Streets, there is a rounded stoop leading to the building's first story. This door is underneath an entablature with a rounded sign reading "THE NEW YORK COCOA EXCHANGE inc."[14][21] Additional entrances were on the building's western end, originally leading to the elevator lobby.[14][17][22] The entrance on Pearl Street, which was formerly located under the Third Avenue elevated line, is more simply designed and contains revolving doors under a canopy.[19] The entrance at Beaver Street has a pediment with carvings of beavers framing a cartouche with the words "munson line building".[21][22][23] The other windows on the first story are generally double-height windows, indicating the presence of the mezzanine inside.[19] Above the second story are ornamental cartouches over carvings of beaver heads.[21][22][23] There are panels between the window groupings on the third story, and a cornice over the third story.[21]

The nine-story shaft is composed of alternating bands of buff and tan brick. The windows are surrounded by glazed green terracotta tiles. The three-story capital is ornamented with multicolored glazed terracotta tiles in green, cream, and russet hues.[7][19][21] The windows are separated into pairs surrounded by double-story neoclassical outlines.[21] The terracotta was originally sandblasted to reduce the glaze.[17][19][23] The top of the building contains a terracotta cornice.[21][23] The cornice originally contained copper cresting, although that was removed after 1940.[19] The roof has a gravel surface, and contains a skylight and some heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) equipment.[24]

Features

[edit]1 Wall Street Court contains a superstructure made entirely of steel. The floor arches and partitions are made of fireproof brick. In the original layout, all woodwork was covered with fireproof materials; the floors of the corridors were made of mosaic and marble, while the office floors were made of cement.[25] 1 Wall Street Court contains four elevators along its western side.[4][26][27] An enclosed fire stair with marble treads is on the building's northwest corner.[25][27] As built, 1 Wall Street Court also had two 300 horsepower (220 kW) boilers that provided steam for three electric generators aggregating 275 kilowatts (369 hp).[26]

The total amount of interior space is about 90,000 square feet (8,400 m2).[28] The first-story and mezzanine space was intended to be used by banks, while the basement was reserved for restaurants.[10][20][25] The basement still serves as its original purpose, but the National Park Service could not determine if a bank ever used the first story and mezzanine. The first floor is about 4 feet (1.2 m) above street level and contains lobbies, commercial space, and elevator access. The main lobby on Pearl Street and the freight lobby on Beaver Street are connected by a corridor with four elevators. The commercial space is accessed by the corner entrance, which contains a wooden vestibule with a revolving door.[20] The elevator lobby contains a barrel-vaulted ceiling, wood-paneled and mirrored walls, and wood-and-metal elevator doors. The mezzanine, a U-shaped space above 2⁄3 of the first floor, is reached by a stair on the west side.[27]

The second floor was used as office space for its first hundred years. A "typical floor" would have an elevator landing on the west, a corridor extending east, and offices on either side of the corridor as well as at the narrow corner.[7][27] The corridors were originally made of mosaic and marble, while the office floors were cement,[25][29] and there were glass panels along the corridors prior to the building's 1937 renovation.[29][30] In the original layout, toilets were placed on the second, fourth, and tenth floors.[25] Because of the interior arrangement and small lot size, all of the interior space was directly lit by a window. Architects' and Builders' Magazine said upon the building's completion that 1 Wall Street Court contained possibly "a larger window area relative to floor space than in any other office building in the city".[31][32][33] Further renovations led to the replacement of the floors, walls, and doors.[34] By 2006, the office space was converted to 126 condominium apartments.[35]

History

[edit]Construction

[edit]

During the late 19th century, builders began erecting tall office buildings in New York City, especially in Lower Manhattan, where they were compelled to build tall structures due to a lack of available land.[36] One such project was led by the Century Realty Company, who hired Clinton and Russell in 1903 to design a speculative development on a narrow lot at Beaver and Pearl Streets.[10] The Remington Construction Company was hired as the contractor for the building, which was planned to cost $600,000.[10][16]

Work began in June 1903.[10] Ownership of the Beaver Building was transferred the next month to the Beaver and Wall Street Corporation.[10][16] During construction, some of the workers went on strike, prompting the Remington Construction Company to hire longshoremen for the project.[11] Construction was completed in October 1904.[10] Original floor plans indicate that the first story had a partition between the two commercial spaces to the west and east; only the western space had a mezzanine.[7][20]

Munson Line use

[edit]The Munson Line, a steamship-line company operating from the United States to the Caribbean and South America,[18][37] took up offices in the Beaver Building in May 1904.[38] The building was sold to the Hoffman family in 1905 for $1.25 million in cash.[39][40] The New York Times described the transaction as the "first cash purchase of a downtown skyscraper reported in several years".[40]

The Munson Steamship Line bought the Beaver Building in July 1919, when the building was estimated to be worth $1.5 million.[6] The Beaver Building was intended as the headquarters of the Munson Line, so it was renamed the Beaver-Munson Building.[30] Shortly afterward, the company announced plans for the 25-story Munson Building at 67 Wall Street, across Beaver Street from the Beaver Building.[41] When the Munson Building opened in 1921, it replaced the Beaver Building as the Munson Line's headquarters.[18][38] The Munson Line retained ownership of the Beaver Building, which continued to be occupied by tenants involved mainly in shipping, produce, and importing and exporting. However, by the 1930s, these tenants had started to move elsewhere,[30] and the Munson Line itself suffered from financial difficulties throughout the 1920s and 1930s.[18][37] A first mortgage loan of $750,000 was placed on the Beaver Building in 1928.[42]

Cocoa Exchange use

[edit]

In April 1931, the New York Cocoa Exchange—at the time described by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and The New York Times as the world's largest cocoa market—moved to the Beaver-Munson Building from its original headquarters at 124 Water Street.[18][43][44] By 1937, the Munson Building Corporation had a debt of $831,690, and the Beaver Building was foreclosed upon. The Beaver Building and a four-story extension at 80 Beaver Street went up for auction in April 1937. The winning bid was from the Bowery Savings Bank, who had bid $500,000.[9]

The New York Cocoa Exchange leased more space in the Beaver Building in June 1937. As part of the lease extension, the Bowery Savings Bank hired F. P. Platt & Bros to expand the mezzanine above the first floor for the Cocoa Exchange's use,[45][46] increasing the exchange's floor area from 2,300 square feet (210 m2) to 5,600 square feet (520 m2).[47] In October 1937, the bank announced plans to renovate the building at a cost of between two and three hundred thousand dollars. The Beaver Building's electrical, heating, and plumbing systems would be replaced, and the facade would be extensively cleaned. The interiors would also receive major modifications, with new automatic elevators and rearranged interior partitions. The first floor partition wall was relocated to the west and a new stair was built to the mezzanine.[20][30]

The Bowery Savings Bank sold the Beaver Building and its four-story annex in 1944 to investor Jerome Greene; at the time, the annex housed the Swan Club.[48] The building was sold again in 1951, this time to an investment syndicate represented by lawyer David Rapoport. At the time, the Buffet Exchange Restaurant and the Cocoa Exchange were both lessees of the space.[49] Records indicate that the lobby was renovated again during 1952, during which deteriorated marble paneling was removed.[27] Sources disagree on the order of subsequent sales. According to The New York Times, the property was then sold to Klausner Associates, and then to investor Arthur H. Bienenstock in 1959, with the latter planning to renovate the elevators and clean the exterior.[50] However, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission states that 82 Beaver Company owned the Cocoa Exchange Building between 1951 and 1981.[16][18] The Cocoa Exchange moved to 127 John Street in 1972.[18][37][51]

Later use

[edit]In January 1985, British developers London & Leeds acquired the Beaver Building, at which point about 70 percent of the space was vacant. After purchasing the building, London & Leeds renamed it One Wall Street Court and renovated the interior, refurbishing the lobby, elevators, and electrical and HVAC systems.[52] Inside, the first-floor partition wall was removed and the mezzanine stair was again replaced.[27] In addition, various improvements were made to the exterior; new windows and window louvers were installed, the base masonry was painted, and metal lights were fixed.[13][27] The windows in the basement were covered over.[14] The building was purchased in 1994 by Cocoa Partners, a limited partnership based in Cohasset, Massachusetts.[16][18]

Sometime after the Cocoa Exchange moved out, the commercial space was occupied until 2002 by a large shop called J&R Discount Cigars.[53] By mid-2004, 1 Wall Street Court was undergoing conversion into a residential building.[54] The conversion was completed around 2006, and the building became a residential condominium development with 126 units.[35][55] A sushi restaurant was also opened at the building's base.[56] The building was used as the setting for the exterior shots of the Continental Hotel in the 2014 film John Wick.[57]

Reception

[edit]1 Wall Street Court was one of the first tall structures in New York City to use multicolored glazed terracotta. Prior to the 1920s, few buildings in the city used this type of material, exceptions including the Madison Square Presbyterian Church and the Broadway–Chambers Building.[17][58][59] The writer Herbert Croly, in an Architectural Record article, was a proponent of such decoration.[60] However, he was critical of its use on 1 Wall Street Court, saying that the tiles did not "harmonize with each other, nor do they constitute a pleasing scheme of decoration for the top stories of a tall building".[17][58][59] Architects' and Builders' Magazine, conversely, stated that the terracotta panels served "to strengthen the outline of the building and make it a notable feature amid its surroundings".[17][61][62]

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission made 1 Wall Street Court an official city landmark on February 13, 1996.[3] The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 6, 2005.[1] In 2007, the building was designated as a contributing property to the Wall Street Historic District,[2] a NRHP district.[63]

See also

[edit]- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan below 14th Street

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan below 14th Street

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c "National Register of Historic Places 2005 Weekly Lists" (PDF). National Park Service. 2005. pp. 162–163. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ a b Howe, Kathy; Robins, Anthony (August 3, 2006). "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form: Wall Street Historic District". National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved July 7, 2024 – via National Archives.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d "Cocoa Exchange". Emporis. Archived from the original on September 5, 2016. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ a b "NYCityMap". NYC.gov. New York City Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ a b "Munson S. S. Line Buys Tall Building on Beaver Street". New-York Tribune. July 1, 1919. p. 21. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b c d e Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1904, p. 515.

- ^ "Appointed Agent". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 11, 1941. p. 17. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b "15-Story Unit Bid in by Bowery Savings; Munson-Beaver And Four-Story Extension Go to Bank at Auction for $500,000". The New York Times. April 20, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 2.

- ^ a b "This Week in Realty". New-York Tribune. December 27, 1903. p. 8. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ National Park Service 2005, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c d e f National Park Service 2005, p. 3.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 2005, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f National Park Service 2005, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e National Park Service 2005, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, p. 5.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2005, pp. 3–4.

- ^ a b c d Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1904, p. 520.

- ^ National Park Service 2005, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c d e Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1904, p. 521.

- ^ a b Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1904, p. 522.

- ^ a b c d e f g National Park Service 2005, p. 6.

- ^ Kennedy, Shawn G. (February 15, 1989). "Real Estate; Wall Street Office Rents Are Bearish". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2005, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d "Bank Will Alter 15-Story Building; Bowery Savings Plans Changes in Landmark at Pearl and Beaver Streets". The New York Times. October 24, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ National Park Service 2005, p. 12.

- ^ Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1904, pp. 520–521.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission 1996, pp. 3–4.

- ^ National Park Service 2005, p. 7.

- ^ a b "1 Wall Street Court". CCM. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ Birkmire, William H. (1898). The Planning and Construction of High Office-Buildings. J. Wiley & Sons. pp. 7–8.

- ^ a b c National Park Service 2005, p. 10.

- ^ a b "Munson Building Opens; Steamship Company Completes Project Begun a Year Ago". The New York Times. May 8, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "For Beaver Building $1,250,000". New-York Tribune. March 11, 1905. p. 5. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b "In the Real Estate Field; Dewsnap Property Near Hanover Square Sold for $400,000 – Hoffmans Buy Beaver Building – New Hotel on Park Avenue in Million-Dollar Trade". The New York Times. March 11, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Munson Steamship Line Going Ahead With Project at Wall and Pearl Streets Where Stock Exchange Stood. The New Munson Building". The New York Times. April 18, 1920. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "$705,000 Lent on Tall Beaver Street Building". New York Herald-Tribune. May 12, 1925. p. 25. Retrieved August 18, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "N.Y. Cocoa Exchange Going to New Home". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. April 25, 1931. p. 23. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Cocoa Exchange Moves To New Trading Quarters". The New York Times. April 26, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Quarters Widened by Cocoa Exchange; Ground Floor of 80–92 Beaver St. To Be Altered to Give Traders More Space". The New York Times. July 17, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Cocoa Exchange to Stay; In Beaver St. Location". New York Herald-Tribune. July 19, 1937. p. 26. Retrieved August 18, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Cocoa Exchange Alterations Adding to Floor Space". Wall Street Journal. September 17, 1937. p. 4. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved August 18, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "2 Buildings Sold on Beaver Street; Financial District Deal Is One of Many in Manhattan by Savings Banks". The New York Times. February 21, 1944. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Beaver St. Realty Sold to Syndicate; 15-Story Cocoa Exchange Building Changes Hands-- Houses Dominate City Trading". The New York Times. July 13, 1951. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Investor Takes Cocoa Building; Buys 15-Story Exchange on Beaver Street – Other Manhattan Deals". The New York Times. March 17, 1959. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Ennis, Thomas W. (May 2, 1972). "Cocoa Unit Opens at New Quarters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Kennedy, Shawn G. (March 10, 1985). "Postings; Saving a Triangle". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Lights Out, Party's over (For Real)". U.S. Banker. Vol. 113, no. 6. June 2003. p. 18 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Joshi, Pradnya (October 15, 2004). "At Home on Wall Street, Developers Are Converting Old Office Buildings into Luxurious New Residences". Newsday. p. D08. Retrieved August 11, 2020 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Development Du Jour: The Cocoa Exchange". Curbed NY. April 19, 2006. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Benihana Inc.'s Haru Sushi Restaurant Heading Downtown to the Financial District; Company Signs Lease Agreement to Open at One Wall Street Court". Business Wire. April 10, 2006. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "The Continental Hotel in John Wick". Legendary Trips. November 21, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ^ a b National Park Service 2005, p. 13.

- ^ a b Croly 1906, p. 322.

- ^ Croly 1906, p. 319.

- ^ Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1904, pp. 515, 520.

- ^ National Park Service 2005, pp. 15–16.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places 2007 Weekly Lists" (PDF). National Park Service. 2007. p. 65. Retrieved July 20, 2020.

Sources

[edit]- "Beaver Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 13, 1996.

- Croly, Herbert D. (April 1906). "Glazed and Colored Terra-Cotta" (PDF). Architectural Record. Vol. 19. p. 322.

- "Historic Structures Report: Beaver Building" (PDF). National Park Service, National Park Service. July 6, 2005.

- "The Beaver Building". Architects' and Builders' Magazine. Vol. 36. August 1904. pp. 514–522.

External links

[edit] Media related to 1 Wall Street Court at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 1 Wall Street Court at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- 1904 establishments in New York City

- Buildings and structures on the National Register of Historic Places in Manhattan

- Financial District, Manhattan

- Office buildings completed in 1904

- Renaissance Revival architecture in New York City

- Residential buildings in Manhattan

- Wall Street

- Triangular buildings

- Historic district contributing properties in Manhattan

- Individually listed contributing properties to historic districts on the National Register in New York (state)