Lone Wolf and Cub

| Lone Wolf and Cub | |

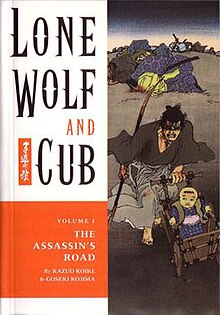

Cover art by Frank Miller of Lone Wolf and Cub vol. 1 (English version), featuring Ogami Ittō (top) and Daigorō (bottom) | |

| 子連れ狼 (Kozure Ōkami) | |

|---|---|

| Genre | |

| Manga | |

| Written by | Kazuo Koike |

| Illustrated by | Goseki Kojima |

| Published by | Futabasha |

| English publisher | |

| Magazine | Weekly Manga Action |

| Demographic | Seinen |

| Original run | September 10, 1970 – April 1, 1976 |

| Volumes | 28 |

| Sequels | |

| |

Lone Wolf and Cub (Japanese: 子連れ狼, Hepburn: Kozure Ōkami, "Wolf taking along his child") is a Japanese manga series created by writer Kazuo Koike and artist Goseki Kojima. It was serialized in Futabasha's Seinen manga magazine Weekly Manga Action from September 1970 to April 1976, with its chapters collected in 28 tankōbon volumes. The story was adapted into six films starring Tomisaburo Wakayama, four plays, and a television series starring Kinnosuke Yorozuya, and is widely recognized as an important and influential work.[3]

Lone Wolf and Cub chronicles the story of Ogami Ittō, the shōgun's executioner who uses a dōtanuki battle sword. Disgraced by false accusations from the Yagyū clan, he is forced to take the path of the assassin. Along with his three-year-old son, Daigorō, they seek revenge on the Yagyū clan and are known as "Lone Wolf and Cub".

Lone Wolf and Cub is considered to be among the most influential manga ever created.[4] It has been cited as the origin for the trope of a man protecting a child on a journey across a dangerous landscape. This is known as the Lone Wolf and Cub trope or genre, which has since inspired numerous books, comics, films, television shows and video games.[5][6][7]

Plot

[edit]Ogami Ittō, formidable warrior and a master of the suiō-ryū swordsmanship, serves as the Kogi Kaishakunin (the Shōgun's executioner), a position of high power in the Tokugawa shogunate during the 1700s.[8] Along with the oniwaban and the assassins, Ogami Ittō is responsible for enforcing the will of the shōgun over the daimyōs (lesser domain lords). For those samurai and lords ordered to commit seppuku, the Kogi Kaishakunin assists their deaths by decapitating them to relieve the agony of disembowelment; in this role, he is entitled and empowered to wear the hollyhock crest of the Tokugawa clan, in effect acting in place of the shōgun.[9]

After Ogami Ittō's wife Azami gives birth to their son, Daigorō, Ogami Ittō returns to find her and all of their household brutally murdered, with only the newborn Daigorō surviving. The supposed culprits are three former retainers of an abolished clan, avenging the execution of their lord by Ogami Ittō. However, the entire matter was planned by Yagyū Retsudō, leader of the Ura-Yagyū (Shadow Yagyu) clan, in order to seize Ogami's post as part of a masterplan to control the three key positions of power: the spy system, the official assassins and the Shogunate Decapitator. During the initial incursion, an ihai (funeral tablet) with the shōgun's crest on it was placed inside the Ogami family shrine, signifying a supposed wish for the shogun's death. When the tablet is "discovered" during the murder investigation, its presence condemns Ittō as a traitor and thus he is forced to forfeit his post and is sentenced, along with Daigorō, to commit seppuku.

The one-year-old Daigorō is given a choice by his father: a ball or a sword. If Daigorō chose the ball, his father would kill him to send Daigorō to be with his mother; however, the child crawls toward the sword and reaches for its hilt; this assigns him the path of a rōnin. Refusing to kill themselves and fighting free from their house imprisonment, father and son begin wandering the country as "demons"—the assassin-for-hire team that becomes known as "Lone Wolf and Cub", vowing to destroy the Yagyū clan to avenge Azami's death and Ittō's disgrace.

On meifumadō ("The Road to Hell"), the cursed journey for vengeance, Ogami Ittō and Daigorō experience numerous adventures. They encounter (and slay) all of Yagyū Retsudō's children (both legitimate and illegitimate) along with the entire Kurokuwa ninja clan, eventually facing Retsudō himself. When Retsudō and the Yagyū clan are unable to kill Ittō, the shogunate officially proclaims him and Daigorō outlaws with a price on their heads, authorizing all clans to try and arrest/kill them and permitting anyone to go after them for the bounty. The last duel between Ogami Ittō and Yagyū Retsudō runs 178 pages—one of the longest single fight-scenes ever published in a manga.[citation needed]

Toward the end of their journey, Ogami Ittō's dōtanuki sword is surreptitiously tampered with and damaged by a supposed sword-polisher who is really an elite kusa ("Grass" ninja) of the Yagyū clan. When Ittō is finally attacked by the last of the kusa, the sword breaks and Ittō receives wounds that are ultimately fatal. Deadlocked in mid-battle with Retsudō, Ittō's spirit leaves his body after years of fatigue and bloodshed, unable to destroy his longtime enemy and ending his path of meifumadō.

The story finishes with Daigorō taking up Retsudō's broken spear and charging in fury. Retsudō opens his arms, disregarding all defense, and allows Daigorō to drive the spear into his body. Embracing Daigorō with tears, Retsudō names him "grandson of my heart", closing the cycle of vengeance and hatred between the clans and concluding the epic.

Many of the stories are written in a non-chronological order, revealing different parts of the narrative at different times. For example, Ogami's betrayal is not revealed until the end of the first volume, after many stories have already passed.

Creation and conception

[edit]In crafting a weakness for his protagonist (in order to make the story interesting), writer Kazuo Koike was inspired by the legendary Sigurd, who is made invulnerable by bathing in a dragon's blood—except for where a leaf shields part of his back and retains his mortality. The character of Daigorō was created to satisfy this need.[10]: 2:00

Koike stated in an interview that he crafted the manga to be based upon the characters themselves and that the "essential tension between [Ittō's] imperative to meet these challenges while keeping his son with him on the journey" drove the story.[11] According to Koike, "Having two characters as foils of each other is what sets things in motion" and that "If you have a strong character, the storyline will develop naturally, on its own."[11]

Less than a year after the manga's debut, Tomisaburo Wakayama came to Koike to propose starring in the films, to which he immediately agreed.[10]: 4:00

According to Koike, he knew from the beginning that being killers themselves, both Ogami and Retsudō must die at the end, while Daigorō should survive. Both the producers of the 1970s television series and magazine publisher opposed this, so he had to end his story in his way "without their permission".[10]: 9:00

Characters

[edit]- Ogami Ittō (拝 一刀)—The shogun's executioner, Ittō decides to avenge the death of his wife, Ogami Azami (拝 薊, "Asami" in the Dark Horse version) and to restore his clan.

- Ogami Daigorō (拝 大五郎, romanized as "Daigoro" in the Dark Horse version)—The son of Ittō and Azami, Daigorō becomes a stronger warrior as the story progresses.

- Yagyū Retsudō (柳生 烈堂)—The leader of the Shadow Yagyū clan, Retsudō tries everything in his power to ensure that Ittō dies.

- Abe Tanomo (阿部 頼母, also known as Kaii (怪異))—The shogun's food taster and a master of poisons; originally ordered to assist Retsudō in disposing of Ittō, Tanomo dishonorably tries to kill Ittō, Daigorō and Retsudō in order to seize power for himself. In the original TV series, his character was introduced in Episode 13 of the third series, "Moon of Desire".

Media

[edit]Manga

[edit]Japan

[edit]Written by Kazuo Koike and illustrated by Goseki Kojima, Lone Wolf and Cub was serialized in Futabasha's Seinen manga magazine Weekly Manga Action. Its first installment was published on September 10, 1970.[12][13] The series finished with the 145th installment published on April 1, 1976.[14][15][16] Futabasha collected its chapters in 28 tankōbon volumes, published from May 1972 to May 1976.[17][18] When Lone Wolf and Cub was first released in Japan in 1970, it became wildly popular for its powerful, epic samurai story and its stark and gruesome depiction of violence during Tokugawa era Japan. As of October 2006, the manga had sold 8.3 million copies in Japan, and 11.8 million worldwide.[19]

Lone Wolf and Cub is one of the most highly regarded manga due to its epic scope, detailed historical accuracy, masterful artwork and nostalgic recollection of the bushido ethos.[citation needed] The story spans 28 volumes of manga, with over 300 pages each (totaling over 8,700 pages in all). Many of the panels of the series are depictions of nature, historical locations in Japan, and traditional activities. A couple of years into the series, a story depicts the fate of Yamada Asaemon, the main character of Samurai Executioner, also created by Koike and Kojima.[20][21] One reviewer notes that Asaemon looks different in this appearance, apparently due to Ogami Ittō having been designed so similarly to the original Asaemon.[22]

North America

[edit]Lone Wolf and Cub was initially released in North America in a translated English edition by First Comics in 1987.[23] The monthly series of comic-book-sized issues featured covers by Frank Miller, Bill Sienkiewicz, Matt Wagner, Mike Ploog, and Ray Lago. Sales were initially strong but fell sharply as the company went into a general decline.[citation needed] First Comics shut down in 1991 without completing the series, publishing less than a third of the total series over 45 issues.

Starting in September 2000, Dark Horse Comics began to release an English translation of the full series in 28 smaller-sized trade paperback volumes with longer page-counts (from 260 to over 300 pages), similar to the volumes published in Japan. Dark Horse completed the presentation of the entire series, fully translated, with the publication of the 28th volume in December 2002. Dark Horse reused all of Miller's covers from the First Comics edition, as well as several done by Sienkiewicz, and commissioned Wagner, Guy Davis, and Vince Locke to produce new covers for several volumes of the collections. In October 2012, Dark Horse completed the release of all 28 volumes in digital format, as part of their "Dark Horse Digital" online service.

Volumes

[edit]|

1. The Assassin's Road |

8. Chains of Death |

15. Brothers of the Grass |

22. Heaven & Earth |

Dark Horse Omnibus collected editions

[edit]

Starting in May 2013, Dark Horse began publishing their translated editions of Lone Wolf and Cub in value-priced Omnibus editions.

| Vol. | Volumes Collected | ISBN | Publication Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1, 2, 3* | 978-1-61655-134-6 | May 2013 |

| 2 | 3*, 4, 5 | 978-1-61655-135-3 | August 2013 |

| 3 | 6, 7, 8* | 978-1-61655-200-8 | November 2013 |

| 4 | 8*, 9, 10* | 978-1-61655-392-0 | April 2014 |

| 5 | 10*, 11, 12 | 978-1-61655-393-7 | July 2014 |

| 6 | 13, 14, 15* | 978-1-61655-394-4 | October 2014 |

| 7 | 15*, 16, 17* | 978-1-61655-569-6 | January 2015 |

| 8 | 17*, 18, 19* | 978-1-61655-584-9 | April 2015 |

| 9 | 19*, 20, 21* | 978-1-61655-585-6 | July 2015 |

| 10 | 21*, 22, 23 | 978-1-61655-806-2 | October 2015 |

| 11 | 24, 25, 26* | 978-1-61655-807-9 | January 2016 |

| 12 | 26*, 27, 28[1] | 978-1-61655-808-6 | April 2016 |

Partial volumes collected in Omnibus form are marked with an asterisk (*).

Sequels and follow-up series

[edit]In 2002, a "reimagined" version of the story, Lone Wolf 2100, was created by writer Mike Kennedy and artist Francisco Ruiz Velasco with Koike's indirect involvement. The story was a post-apocalyptic take on the tale with several differences, such as a female cub and a worldwide setting: Daisy Ogami, daughter of a renowned scientist, and Itto, her father's cybernetic bodyguard and Daisy's subsequent protector, attempt to escape from the Cygnat Owari Corporation's schemes.

Dark Horse announced at the 2006 New York Comic Con that they had licensed New Lone Wolf and Cub, Kazuo Koike and Hideki Mori's follow-up to Lone Wolf and Cub, starring Ogami Itto's son Daigoro, the famous child in the baby cart.[24] In this new series, which picks up immediately after the climactic battle of the original series, the bodies of Ogami Itto and Yagyu Retsudo are left lying on the beach with Daigoro left alone standing over his father's body (since no one, for political reasons, dares to bury either body or take charge of Daigoro). A bearded samurai, Tōgō Shigetada of the Satsuma clan and master of the Jigen-ryū style of swordsmanship (based on the actual historical personage Tōgō Shigetaka, creator of Jigen-ryū), wanders onto the battlefield and assists Daigoro with the cremation/funeral of Ogami Itto and Yagyu Retsudo. Tōgō, who is on a training journey and also carries a dotanuki sword similar to Ogami's (and crafted by the same swordsmith), then assumes guardianship of Daigoro, including retrieving the baby cart and teaching/training Daigoro in Jigen-ryū.

The two soon become enmeshed in a plot by the Shogunate conceived by the ruthless Matsudaira Nobutsuna and spearheaded by his chief henchman Mamiya Rinzō (also based on an actual historical character) to topple the Satsuma clan and assume control of that fiefdom's great wealth, using Tōgō as an unwitting pawn. When Tōgō discovers that he has been tricked and used, he and Daigoro embark on the road of meifumado in a quest to kill the Shogun (which would force Matsudaira out into the open). However, Rinzō, who is not only a master of disguise but also Matsudaira's natural son, may have an even more devious plan of his own, including subverting the Shogun's own ninja and using opium to ensnare and enslave the Shogun himself. This series also introduces non-Japanese characters into the plotlines. Dark Horse began publishing the follow-up series, New Lone Wolf and Cub, in June 2014;[25] the eleventh and last volume was released in December 2016.

A second sequel series, titled [[[Soshite Kozure Ōkami: Shikaku no Ko]]] Error: {{nihongo}}: transliteration text not Latin script (pos 114) (help) (そして――子連れ狼 刺客の子, lit. 'More Lone Wolf and Cub: Eyes of the Child'), was serialized in Koike Shoin's manga magazine Jin from January 20, 2007,[26] until the magazine's last issue, released on May 21, 2008.[27][28] The series resumed on eBookJapan's online manga magazine Katana on April 14, 2009,[29][30] and finished on July 20, 2010.[31] Five volumes were released by Koike Shoin from July 27, 2007,[32] to September 28, 2012.[33] This series has not currently been translated into English.

Films

[edit]A total of six Lone Wolf and Cub films starring Tomisaburo Wakayama as Ogami Ittō and Tomikawa Akihiro as Daigoro were produced based on the manga. They are also known as the Sword of Vengeance series, based on the English-language title of the first film, and later as the Baby Cart series, because young Daigoro travels in a baby carriage pushed by his father.

The first three films, directed by Kenji Misumi, were released in 1972 and produced by Shintaro Katsu, Wakayama's brother and the star of the 26-part Zatoichi film series. The next three films were produced by Wakayama himself and directed by Buichi Saitō, Kenji Misumi, and Yoshiyuki Kuroda, released in 1972, 1973, and 1974, respectively. Wakayama quit making the films after the popular television series began to air.[34]

Shogun Assassin (1980) was an English language compilation for the American audience, edited mainly from the second film, with 11 minutes of footage from the first. Also, the third film, Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades was re-released on DVD in the US under the name Shogun Assassin 2: Lightning Swords of Death.

| No. | English Title | Year | Japanese | Romanization | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lone Wolf and Cub: Sword of Vengeance | 1972 | 子連れ狼 子を貸し腕貸しつかまつる | Kozure Ōkami: Kowokashi udekashi tsukamatsuru | Wolf with Child in Tow: Child and Expertise for Rent |

| 2 | Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart at the River Styx | 1972 | 子連れ狼 三途の川の乳母車 | Kozure Ōkami: Sanzu no kawa no ubaguruma | Wolf with Child in Tow: Baby Cart of the River of Sanzu |

| 3 | Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart to Hades AKA Shogun Assassin 2: Lightning Swords of Death | 1972 | 子連れ狼 死に風に向う乳母車 | Kozure Ōkami: Shinikazeni mukau ubaguruma | Wolf with Child in Tow: Baby Cart Against the Winds of Death |

| 4 | Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in Peril AKA Shogun Assassin 3: Slashing Blades of Carnage | 1972 | 子連れ狼 親の心子の心 | Kozure Ōkami: Oya no kokoro ko no kokoro | Wolf with Child in Tow: The Heart of a Parent, the Heart of a Child |

| 5 | Lone Wolf and Cub: Baby Cart in the Land of Demons AKA Shogun Assassin 4: Five Fistfuls of Gold | 1973 | 子連れ狼 冥府魔道 | Kozure Ōkami: Meifumado | Wolf with Child in Tow: Land of Demons |

| 6 | Lone Wolf and Cub: White Heaven in Hell AKA Shogun Assassin 5: Cold Road to Hell | 1974 | 子連れ狼 地獄へ行くぞ!大五郎 | Kozure Ōkami: Jigoku e ikuzo! Daigoro | Wolf with Child in Tow: Now We Go to Hell, Daigoro! |

| 7 | Shogun Assassin | 1980 | An English language dubbed film with 12 minutes from Sword of Vengeance and most of Baby Cart at the River Styx. | ||

In 1992 the story was again adapted for film, Lone Wolf and Cub: Final Conflict also known as Handful of Sand or A Child's Hand Reaches Up (Kozure Ōkami: Sono Chiisaki te ni, literally In That Little Hand), directed by Akira Inoue and starring Masakazu Tamura as Ogami Itto.

| English Title | Year | Japanese | Romanization | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lone Wolf and Cub: Final Conflict | 1993 | 子連れ狼 その小さき手に | Kozure Ōkami: Sono Chiisaki te ni | Lone Wolf and Cub: Final Conflict |

In addition to the six original films (and Shogun Assassin in 1980), various television movies have aired in connection with the television series as pilots, compilations or originals. These include several starring Kinnosuke Yorozuya (see section Television series), in 1989 a TV movie called Lone Wolf With Child: An Assassin on the Road to Hell better known as Baby Cart In Purgatory where Hideki Takahashi plays Ogami Ittō and Tomisaburo Wakayama co-stars as Retsudo Yagyu.

Hollywood remake

[edit]In the 2000s, Darren Aronofsky attempted to get an official Hollywood version of Lone Wolf and Cub off the ground, but could not secure the rights.[35][36]

In March 2012, Justin Lin was announced as the director on an American version of Lone Wolf and Cub.[37] In June 2016, it was announced that producer Steven Paul had acquired the rights,[38] and in October 2017, it was announced that Andrew Kevin Walker writing the script.[39]

Television series

[edit]Two full-fledged television series based on the manga have been broadcast to date.

The first, Lone Wolf and Cub (Kozure Ōkami), was produced in a typical jidaigeki format and broadcast for three seasons from 1973 to 1976, each episode 45 minutes long. Season one originally aired 27 episodes, but the original 2nd episode "Gomune Oyuki (Oyuki of the Gomune)" was subsequently deleted from all rebroadcasts in Japan and VHS and DVD releases; the reasons why this episode has been excluded are currently unclear. Seasons two and three ran for 26 episodes each. Kinnosuke Yorozuya played Ogami Ittō, and later reprised the role in a 1984 TV movie; Daigoro was played by Katzutaka Nishikawa in the first two seasons and by Takumi Satô in the final season.

The series was co-produced by Union Motion Picture Co, Ltd. (ユニオン映画) and Studio Ship (スタジオシップ), a company formed by manga author Kazuo Koike, and originally aired on Nippon TV in Japan. It was subsequently broadcast in the United States as The Fugitive Samurai in the original Japanese with English subtitles, and released for the Toronto, Canada market by CFMT-TV (now OMNI 1) in the original Japanese with English subtitles as The Iron Samurai. It has also been aired in Germany dubbed in German, in Italy dubbed in Italian; around 1980, a Portuguese dub was aired in Brazil as O Samurai Fugitivo (The Fugitive Samurai) on TVS, actually SBT, and in Spanish, as El Samurai Fugitivo on the American Spanish TV station Univision.

The first season was released on DVD in Japan on December 20, 2006, apparently without subtitles. Twelve of the first 13 episodes were released on DVD in Germany as Kozure Okami, with audio in Japanese and German. In the U.S., Media Blasters released the first season on DVD on April 29, 2008, under its Tokyo Shock Label, containing the original Japanese with English subtitles. All of these releases excluded the deleted-from-distribution 2nd episode "Gomune Oyuki".

The latest television series, also titled Lone Wolf and Cub (Kozure Ōkami), aired from 2002 to 2004 in Japan on TV Asahi with Kin'ya Kitaōji in the role of Ogami Ittō and Tsubasa Kobayashi as Daigoro. This series has not yet been made commercially available on DVD or Blu-ray; however, beginning in September 2023 English-subtitled episodes began being uploaded to the YouTube website, courtesy of the "Samurai vs. Ninja" YouTube Channel,[40] and currently all three seasons of the series have been uploaded.

Games

[edit]In 1987, video game manufacturer Nichibutsu released a beat 'em up arcade video game based on the series, named Kozure Ōkami in Japan[41] and Samurai Assassin overseas.[42] Players guide Ogami Itto through an army of assassins while carrying his infant son on his back.[43] A baby cart powerup enables Ookami to mow down enemies with blasts of fire. The game was only released in arcades.

In 1989, Mayfair Games published Lone Wolf and Cub Game, a board game designed by Matthew Costello based on the franchise.[44] GM Magazine reviewed the game, highlighting the illustrations, well-written encounters, and sturdy components; however, the reviewer found that the basic rules and limited options made for a dull experience on repeat plays.[45]

In the 2001 PlayStation 2 video game Final Fantasy X by Square Enix, there is an aeon named Yojimbo, a being the summoner Yuna can summon to battle, along with his dog Daigoro. He must be paid the game's form of money to use attacks varying in strength and weapon. With his design resembling that of Ancient Japanese designs, his worker-employer relationship with Yuna, the aesthetic with his weaponry and mannerisms, and the name of his dog, many elements from Ittō were used to design this summon.

In 2012, a pachinko game adaptation called Kozure Ōkami was released in Japan.[4]

Library requests

[edit]By 1990, many libraries understood the rise of graphic novels as a medium.[46] Many were advised to purchase copies of various graphic novels to keep up public demand, listing many popular publications. One of the most prominent graphic novels listed was Lone Wolf and Cub, focusing on the Japanese elements in the storytelling. They would continue to add the volumes of the graphic novel well into 2003.[47]

Influence

[edit]Lone Wolf and Cub is considered to be among the most influential manga ever created, having inspired numerous artists, animators and filmmakers across the world,[4] as well as creating the "Lone Wolf and Cub" trope.[7]

Lone Wolf and Cub has influenced American comics, notably Frank Miller in his Sin City and Ronin series.[48] Other examples of artists inspired by it include filmmakers such as Hong Kong action cinema's John Woo when he produced Heroes Shed No Tears (1986), American comic book artists such as Justin Jordan and Mike Kennedy, and animators such as Russia's Genndy Tartakovsky.[4] Indian comic-book writer Suhas Sundar acknowledged that he drew some inspiration from Lone Wolf and Cub to create his Odayan comic book series.[49]

Homages to Lone Wolf and Cub have appeared in many works. Examples include a 1973 television commercial for Momoya chansai seasoning, episode 77 of the anime series Urusei Yatsura (1983), Samurai Champloo episode 22 (2005), Gintama episode six (2006), the third season of Crayon Shin-chan Gaiden (2017) subtitled "Kazokukure Ōkami" ("Lone Wolf and Family"), Busō Shōjo Machiavellism episode six (2017), Hug! Pretty Cure episode 44 (2018), and Rick and Morty: The Anime episode "Samurai & Shogun" (2020).[4]

Lone Wolf and Cub trope

[edit]Lone Wolf and Cub has been cited as the origin for the narrative trope/genre where a man, skilled in violence, protects a child on a journey across a dangerous landscape.[5][6][7] Known as the Lone Wolf and Cub trope or genre, it has since been used in numerous works, with examples including films such as Léon: The Professional (1994) and Logan (2017), television shows such as Stranger Things and Game of Thrones, and media franchises such as The Witcher and The Last of Us.[7][50][51]

The samurai anime film Sword of the Stranger (2007) has been described as "Lone Wolf and Cub" meets Rurouni Kenshin.[52] There are also variations of the Lone Wolf and Cub trope involving a mother and daughter, with examples including films such as Birds of Prey (2020) and Gunpowder Milkshake (2021).[7]

Novelist Max Allan Collins acknowledged the influence of Lone Wolf and Cub on his graphic novel Road to Perdition (1998). In an interview to the BBC, Collins declared that "Road to Perdition is 'an unabashed homage' to Lone Wolf and Cub".[53][54] In turn, writer Neil Druckmann cited Road to Perdition as a direct influence on The Last of Us video game (2013) and television show (2023);[5] The Last of Us actor Pedro Pascal cited Lone Wolf and Cub as the origin of the trope of a man protecting a child on a journey across a dangerous landscape.[6]

"Wolf and Cub" is an episode from the first season of the TV series Person of Interest; the title is assumed to be inspired by Lone Wolf and Cub. Themes of vengeance and being a rōnin are interspersed throughout the episode.[55][56]

Episode 20 of the fifth season of the television series Bob's Burgers, "Hawk & Chick", is a parody inspired by Lone Wolf and Cub.[57] A follow-up episode, "The Hawkening: Look Who's Hawking Now!" from the show's tenth season, features a missing scene that parallels the suppressed episode of the 1973 Lone Wolf and Cub TV series.

The Star Wars streaming series The Mandalorian has a premise influenced by Lone Wolf and Cub, with the titular character guarding an alien child from various threats.[58] The Mandalorian spin-off series The Book of Boba Fett includes a scene modeled on Daigorō's choice between ball and sword as depicted in Sword of Vengeance.[59][60] Obi-Wan Kenobi also uses a variation of the trope.[50]

The Lone Wolf and Cub trope has also been used in numerous video games. Examples include the adaptation Kozure Ōkami (1987),[41] Hanjuku Hero 4 (2005) by Square Enix,[4] The Witcher series,[7] The Last of Us,[6] Hideo Kojima's Death Stranding (2019),[61] and FromSoftware's Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice (2019).[62]

Reception

[edit]In February 2001, Lone Wolf and Cub won the best comic reprint at the 2000 Squiddy Awards,[63] The manga received multiple award at Annual Harvey Awards, In 2001, 2002 and 2003, it won three awards for "Best American Edition of Foreign Material" and in April 2002, at the 15th Annual Harvey Awards, the manga won the "Best Graphic Album of Previously Published Work".[64][65][66][67][68] in July 2001, the Lone Wolf and Cub manga won an Eisner Award in the category of Best U.S. Edition of Foreign Material and at the 2004 Eisner Awards category, it received as one of the Hall of Fame title.[69][70]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Lone Wolf and Cub Omnibus Volume 12 TPB". Dark Horse Comics. Archived from the original on April 30, 2019. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ O'Rourke, Shawn (January 20, 2010). "Lone Wolf and Cub Part 2: Revenge in the Epic Narrative Tradition". PopMatters. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved September 22, 2021.

- ^ Bernardin, Marc (July 19, 2002). "Father Knows Best". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on December 29, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Ask John: Why Isn't there any Lone Wolf & Cub Anime?". AnimeNation. June 7, 2020. Archived from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ a b c Schaefer, Sandy (February 21, 2023). "How Road To Perdition Helped Shape Joel's Parenting Style In The Last Of Us". /Film. Archived from the original on July 17, 2023. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Hibberd, James (January 4, 2023). "How 'The Last of Us' Plans to Bring the Zombie Genre Back to Life". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 4, 2023. Retrieved July 17, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Khan, Nilofer (January 30, 2023). "How 'The Last of Us', 'Stranger Things' and more shows are changing an age old TV trope in a significant way". Mashable. Archived from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ Koike, Kazuo (2001). Lone Wolf and Cub: Volume 5 – Black Wind. Gōseki Kojima, Dana Lewis (1st ed.). Milwaukie, OR: Dark Horse Comics. p. 159. ISBN 1-56971-502-5. OCLC 45712675. Archived from the original on June 12, 2024. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ Koike, Kazuo; Kojima, Gōseki (2000). Lone Wolf and Cub: The Assassin's Road. Milwaukie, OR: Dark Horse Comics. ISBN 1569715025.

- ^ a b c Kazuo Koike on Lone Wolf and Cub (2016). The Criterion Collection.

- ^ a b "Kazuo Koike - The Dark Horse Interview 3/3/06". Dark Horse Comics. March 3, 2006. Archived from the original on March 20, 2006. Retrieved March 8, 2002.

- ^ 週刊漫画アクション 1970年. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on June 15, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "The Manga Top Ten トップテン・マンガ". CBSI Comics. December 19, 2017. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ 週刊漫画アクション 1976年. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on June 15, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Contents". Weekly Manga Action (in Japanese). Futabasha. April 1970. Table of contents. Archived from the original on June 13, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

漫画アクション1976/04/01

- ^ "Contents". gouseki.kazekaworu.com. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

子連れ狼・最終回/其之百四十五腕(かいな)・後編

- ^ 子連れ狼 1. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on June 15, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ 子連れ狼 28. Media Arts Database (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Archived from the original on June 15, 2024. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ "劇画「子連れ狼」の原作者 小池一夫さんが郷土・大仙市に 住所も移し、花館に同級生らと集える自宅". Kitaura Hana Net (in Japanese). October 8, 2006. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- ^ "Dark Horse Comics presents Samurai Executioner, a manga masterwork from the creators of Lone Wolf and Cub! :: Archived Press Releases". Dark Horse Comics. Archived from the original on April 1, 2022. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ "Lone Wolf and Cub Volume 5: Black Wind by Kazuo Koike, Goseki Kojima". Penguin Random House Canada. Archived from the original on August 10, 2022. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Martin, Mick (August 17, 2011). "Review - Lone Wolf & Cub Vol. 5: Black Wind". Superheroes, etc. Archived from the original on November 27, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2021.

- ^ "Lone Wolf and Cub Part 1: History and Influences". PopMatters. December 1, 2009. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- ^ "Dark Horse to Double Manga Output in '06". ICv2. February 27, 2006. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved October 26, 2009.

- ^ "New Lone Wolf and Cub Volume 1". Dark Horse Comics. Archived from the original on December 31, 2014. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ 時代劇漫画 刃-JIN-: 07年3月号発売中!. Jidaigeki Manga Jin (in Japanese). Archived from the original on December 26, 2007. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ 刃 休刊のお知らせ. Jidaigeki Manga Jin (in Japanese). June 19, 2008. Archived from the original on October 2, 2008. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Loo, Egan (June 6, 2008). "Kazuo Koike's Jin Historical Manga Magazine Ends". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on December 16, 2023. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ 有料ウェブマガジンのニューカマー「KATANA」創刊. Comic Natalie (in Japanese). Natasha, Inc. April 7, 2009. Archived from the original on July 2, 2017. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Loo, Egan (April 14, 2009). "Lone Wolf and Cub Manga Resumes in Katana Web Mag". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on December 16, 2023. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Web Magazine KATANA 31号. eBookJapan (in Japanese). Archived from the original on December 31, 2023. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ 『そして――子連れ狼 刺客の子』第1巻 発売!. Kazuo Koike's First Blog (in Japanese). Soeisha. July 27, 2007. Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ 【9月28日付】本日発売の単行本リスト. Comic Natalie (in Japanese). Natasha, Inc. September 28, 2012. Archived from the original on January 4, 2022. Retrieved December 31, 2023.

- ^ Lame d'un père, l'âme d'un sabre (2005). Wild Side Films. Event occurs at 41.

- ^ Franklin, Garth (November 14, 2006). "'Flicker' Over To Darren Aronofsky". Dark Horizons. Archived from the original on November 26, 2006. Retrieved November 14, 2006.

- ^ Loo, Egan (January 7, 2009). "Hollywood's Lone Wolf and Cub No Longer in Development (Updated)". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on February 3, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2009.

- ^ Chitwood, Adam (March 27, 2012). "Kamala Films Acquires 'Lone Wolf And Cub' with 'Fast Five' Director Justin Lin Attached". Collider. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ Frater, Patrick (June 27, 2016). "Iconic Manga 'Wolf and Cub' Set For Remake". Variety. Archived from the original on October 14, 2017. Retrieved April 30, 2019.

- ^ Couch, Aaron; Kit, Borys (October 17, 2017). "'Seven' Writer Andrew Kevin Walker Tackling 'Lone Wolf and Cub' for Paramount (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 17, 2024. Retrieved June 8, 2024.

- ^ ""Lone Wolf and Cub - Episode 01 - Martial Arts Adventure - Ninja vs Samurai"". YouTube. September 2023. Archived from the original on September 3, 2023. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ a b "Kodure Ookami - Videogame by Nichibutsu". Killer List of Videogames. Archived from the original on June 12, 2024. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "Samurai Assassin arcade brochure". Archived from the original on March 25, 2019. Retrieved December 25, 2020.

- ^ 子連れ狼 / 日本物産(1987) [Wolf with a child / Nippon Bussan (1987)]. Karashitakana.boo.jp (in Japanese). Archived from the original on March 22, 2012. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ "Lone Wolf and Cub Game". Board Game Geek. Archived from the original on October 30, 2022. Retrieved October 30, 2022.

- ^ Wayne (March 1990). "Lone World and Cub – The Board Game". G.M. The Independent Fantasy Roleplaying Magazine. Vol. 2, no. 7. Croftward Publishing.

- ^ Decandido, Keith R. A. (March 15, 1990). "Picture This: Graphic Novels in Libraries". Library Journal. 115: 50–55 – via Ebscohost.

- ^ Raiteri, Steve (January 2003). "Koike, Kazuo & Goseki Kojima. Lone Wolf and Cub. Vol. 22: Heaven and Earth". Library Journal. 128: 84 – via Gale in Context.

- ^ Meadows, Joel; Marshall, Gary (2008). "Frank Miller". Studio Space: The World's Greatest Comic Illustrators At Work. Berkeley, CA: Image Comics. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-58240-908-5.

- ^ Sen, Jhinuk (August 25, 2014). "Warning: Graphic content inside". millenniumpost. Archived from the original on October 19, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ a b Rouse, Isaac (June 11, 2023). "'The Last of Us' Retrospective: How a Game Propelled a Franchise Into Mainstream Popularity 10 Years Later". TV Insider. Archived from the original on July 26, 2023. Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- ^ "The Best 90s Movies on Netflix Right Now". Collider. March 6, 2020. Archived from the original on July 26, 2023. Retrieved July 26, 2023.

- ^ "The Daily Stream: Sword Of The Stranger Is Perfect For Fans Of Samurai Movies, Wuxia, And Animation". /Film. February 27, 2023. Archived from the original on July 22, 2023. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ Etherington, Daniel (September 19, 2002). "Road To Perdition". BBC Collective. Archived from the original on October 2, 2002. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- ^ Collins, Max Allan (April 23, 2019). "My Debt to Lone Wolf and Cub's Genius Creator". Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2020.

- ^ Vonder Haar, Pete (February 10, 2012). "Person of Interest: Lone "Wolf and Cub"". Houston Press. Archived from the original on April 20, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ Couzens, Keysha (February 11, 2012). "Person of Interest 1.14 'Wolf and Cub' Review". TV Overmind. Archived from the original on May 7, 2021. Retrieved March 11, 2021.

- ^ Green, Scott (May 17, 2015). "'Bob's Burgers' Season Finale Spoofs 'Lone Wolf and Cub'". Crunchyroll. Archived from the original on July 21, 2018. Retrieved December 29, 2019.

- ^ Favreau, Jon. "Process". Disney Gallery: The Mandalorian. Season 1. Episode 6. June 5, 2020. Disney+.

- ^ Tantimedh, Adi (February 3, 2022). "The Book of Boba Fett Has Lone Wolf and Cub to Thank for E06 Ending". Bleeding Cool. Archived from the original on February 4, 2022. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ Busch, Jenna (February 2, 2022). "Easter Eggs You May Have Missed In The Book Of Boba Fett Episode 6". /Film. Archived from the original on February 4, 2022. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ Navarro, Alex (November 6, 2019). "Death Stranding Review". Giant Bomb. Archived from the original on November 7, 2019. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ Samson, Miguel (April 29, 2019). "Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice Review - Bushido blades and Postured knaves". Too Much Gaming. Archived from the original on June 12, 2024. Retrieved July 22, 2023.

- ^ "Lone Wolf and Cub best comic reprint". Anime News Network. February 27, 2001. Archived from the original on November 4, 2022. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ "Previous Winners". Harvey Awards. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ "Lone Wolf and Cub wins Harvey Award". Anime News Network. April 30, 2001. Archived from the original on April 17, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ "Mangas Nominated for Harvey Awards". Anime News Network. February 27, 2001. Archived from the original on November 13, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ "Harvey Award Nominees Announced". Anime News Network. March 7, 2002. Archived from the original on November 4, 2022. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ Koulikov, Mikhail (September 30, 2008). "Manga Shut Out at Harvey Awards". Anime News Network. Archived from the original on March 2, 2024. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

- ^ "Lone Wolf And Cub Manga Wins Eisner". Anime News Network. July 25, 2001. Archived from the original on April 17, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ "Eisner Awards". Anime News Network. July 24, 2001. Archived from the original on February 7, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2024.

External links

[edit]- Dark Horse Comics: Lone Wolf and Cub manga

- Kodure Ookami at the Killer List of Videogames

- Samurai and Son: The Lone Wolf and Cub Saga an essay by Patrick Macias at the Criterion Collection

- Lone Wolf and Cub (manga) at Anime News Network's encyclopedia

- Manga series

- 1970 manga

- Anime and manga about revenge

- Adventure anime and manga

- Dark Horse Comics titles

- Eisner Award winners

- Epic anime and manga

- Harvey Award winners

- Fiction set in 18th-century Edo period

- First Comics titles

- Futabasha manga

- Gekiga

- Japanese film series

- Kazuo Koike

- Lone Wolf and Cub

- Manga adapted into films

- Samurai in anime and manga

- Seinen manga