1890 Manifesto

As published in the October 15, 1890 edition of the Woman's Exponent | |

| Book | Doctrine and Covenants |

|---|---|

| Category | Official declaration |

The 1890 Manifesto (also known as the Woodruff Manifesto, the Anti-polygamy Manifesto, or simply "the Manifesto") is a statement which officially advised against any future plural marriage in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church). Issued by Church President Wilford Woodruff in September 1890, the Manifesto was a response to mounting anti-polygamy pressure from the United States Congress, which by 1890 had disincorporated the church, escheated its assets to the U.S. federal government, and imprisoned many prominent polygamist Mormons. Upon its issuance, the LDS Church in conference accepted Woodruff's Manifesto as "authoritative and binding."

The Manifesto was a dramatic turning point in the history of the LDS Church. It advised church members against entering into any marriage prohibited by the law of the land,[1] and made it easier for Utah to become a U.S. state. Nevertheless, even after the Manifesto, the church quietly continued to perform a small number of plural marriages in the United States, Mexico, and Canada,[2][3] thus necessitating a Second Manifesto during U.S. congressional hearings in 1904. Though neither Manifesto dissolved existing plural marriages, plural marriage in the LDS Church gradually died by attrition during the early-to-mid 20th century. The Manifesto was canonized in the LDS Church standard works as Official Declaration 1[4][5] and is considered by mainstream Mormons to have been prompted by divine revelation (although not a revelation itself), in which Woodruff was shown that the church would be thrown into turmoil if they did not comply with it.[6] Some Mormon fundamentalists rejected the manifesto.[7]

Background

[edit]| Mormonism and polygamy |

|---|

|

|

|

The Manifesto was issued in response to the anti-polygamy policies of the federal government of the United States, and most especially the Edmunds–Tucker Act of 1887. This law disincorporated the LDS Church and authorized the federal government to seize all of the church's assets. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the provisions of the Edmunds–Tucker Act in Late Corporation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints v. United States in May 1890.[8]

In April 1889, Woodruff, the president of the church, began privately refusing the permission that was required to contract new plural marriages.[9] In October 1889, Woodruff publicly admitted that he was no longer approving new polygamous marriages, and in answer to a reporter's question of what the LDS Church's attitude was toward the law against polygamy, Woodruff stated, "We mean to obey it. We have no thought of evading it or ignoring it."[10] Because it had been Mormon practice for over 25 years to either evade or ignore anti-polygamy laws, Woodruff's statement was a signal that a change in church policy was developing.[11]

In February 1890, the Supreme Court ruled in Davis v. Beason[12] that a law in Idaho Territory which disenfranchised individuals who practiced or believed in plural marriage was constitutional.[13] That decision left the Mormons no further legal recourse to their current marriage practices[14] and made it unlikely that without change Utah Territory would be granted statehood.[citation needed]

Woodruff later said that on the night of September 23, 1890, he received a revelation from Jesus Christ that the church should cease the practice of plural marriage.[15] The following morning, he reported this to some of the general authorities and placed the hand-written draft on a table. George Reynolds would later recount that he, Charles W. Penrose, and John R. Winder modified Woodruff's draft into the current language accepted by the general authorities and presented to the church as a whole.[16] Woodruff announced the Manifesto on September 25 by publishing it in the church-owned Deseret Weekly in Salt Lake City.[17] On October 6, 1890, it was formally accepted by the church membership, though many held reservations or abstained from voting.[2][18][19]

Utah ratified its constitution in November 1895 and was granted statehood on January 4, 1896.[20] One of the conditions for granting Utah statehood was that a ban on polygamy be written into its state constitution.[21][22]

Text

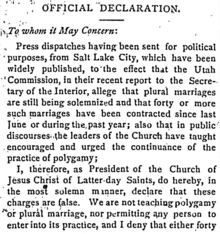

[edit]The Manifesto states:

To Whom It May Concern:

Press dispatches having been sent for political purposes, from Salt Lake City, which have been widely published, to the effect that the Utah Commission, in their recent report to the Secretary of the Interior, allege that plural marriages have been contracted in Utah since last June or during the past year, also that in public discourses the leaders of the Church have taught, encouraged and urged the continuance of the practice of polygamy—

I, therefore, as President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, do hereby, in the most solemn manner, declare that these charges are false. We are not teaching polygamy or plural marriage, nor permitting any person to enter into its practice, and I deny that either forty or any other number of plural marriages have during that period been solemnized in our Temples or in any other place in the Territory.

One case has been reported, in which the parties allege that the marriage was performed in the Endowment House, in Salt Lake City, in the Spring of 1889, but I have not been able to learn who performed the ceremony; whatever was done in this matter was without my knowledge. In consequence of this alleged occurrence the Endowment House was, by my instructions, taken down without delay.

Inasmuch as laws have been enacted by Congress forbidding plural marriages, which laws have been pronounced constitutional by the court of last resort, I hearby declare my intention to submit to those laws, to use my influence with the members of the Church over which I preside to have them do likewise.

There is nothing in my teachings to the Church or in those of my associates, during the time specified, which can be reasonably construed to inculcate or encourage polygamy; and when any Elder of the Church has used language which appeared to convey such teaching, he has been promptly reproved. And I now publicly declare that my advice to the Latter-day Saints is to refrain from contracting any marriage forbidden by the law of the land.

Wilford Woodruff [signed]

President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[23]

Formal acceptance by the LDS Church

[edit]Less than a month after the Manifesto was issued, the LDS Church used the procedure of common consent to make it binding upon church members. At a general conference of the church in Salt Lake City on October 6, 1890, the Manifesto was read, after which Lorenzo Snow, the president of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, made the following motion:

I move that, recognizing Wilford Woodruff as the President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and the only man on the earth at the present time who holds the keys of the sealing ordinances, we consider him fully authorized by virtue of his position to issue the Manifesto which has been read in our hearing, and which is dated September 1890, and that as a Church in General Conference assembled, we accept his declaration concerning plural marriages as authoritative and binding.[23]

The conference proceedings recorded that "the vote to sustain the foregoing motion was unanimous."[23] However, a modern author reports that "at least some voted against the Manifesto and perhaps a majority abstained."[19] Some members, including apostle Moses Thatcher, only reluctantly supported the Manifesto and interpreted it as a sign that the Second Coming of Jesus was imminent, after which plural marriage would be reinstated.[19]

New plural marriages vs. existing plural marriages

[edit]The Manifesto was the end of official church authorization for the creation of new plural marriages that violated local laws. It had no effect on the status of already existing plural marriages, and plural marriages continued to be performed in locations where it was believed to be legal. As Woodruff explained at the general conference where the Manifesto was accepted by the church, "[t]his Manifesto only refers to future marriages, and does not affect past conditions. I did not, I could not, and would not promise that you would desert your wives and children. This you cannot do in honor."[24] Despite Woodruff's explanation, some church leaders and members who were polygamous did begin to live with only one wife.[25] However, the majority of Mormon polygamists continued to cohabit with their plural wives in violation of the Edmunds Act.[26]

Aftermath and post-Manifesto plural marriage

[edit]Within six years of the announcement of the Manifesto, Utah had become a state and federal prosecution of Mormon polygamists subsided. However, Congress still refused to seat representatives-elect who were polygamists, including B. H. Roberts.[27]

D. Michael Quinn and other Mormon historians have documented that some church apostles covertly sanctioned plural marriages after the Manifesto. This practice was especially prevalent in Mexico and Canada because of an erroneous belief that such marriages were legal in those jurisdictions.[28] However, a significant minority were performed in Utah and other western American states and territories. The estimates of the number of post-Manifesto plural marriages performed range from scores to thousands, with the actual figure probably close to 250.[29] Today, the LDS Church officially acknowledges that although the Manifesto "officially ceased" the practice of plural marriage in the church, "the ending of the practice after the Manifesto was ... gradual."[30][2]

Rumors of post-Manifesto marriages surfaced and began to be examined by Congress in the Reed Smoot hearings. In response, church president Joseph F. Smith issued a "Second Manifesto" in 1904 which reaffirmed the church's opposition to the creation of new plural marriages and threatened excommunication for Latter-day Saints who continued to enter into or solemnize new plural marriages. Apostles John W. Taylor and Matthias F. Cowley both resigned from the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles due to disagreement with the church's position on plural marriage.[31] Plural marriage in violation of local law continues to be grounds for excommunication from the LDS Church.[32]

The cessation of plural marriage within LDS Church gave rise to the Mormon fundamentalist movement.[7]

Evolution of Latter-day Saint views on the Manifesto

[edit]| Part of a series on the |

| Doctrine and Covenants |

|---|

|

The Manifesto has been canonized by the LDS Church, and its text appears in the Doctrine and Covenants, one of the church's books of scripture. However, when the Manifesto was issued, it was not apparent that Woodruff or the other leaders of the LDS Church viewed it as the result of a divine revelation.[33]

Approximately one year after he declared the Manifesto, Woodruff began to claim that he had received instructions from Jesus Christ that formed the basis of what he wrote in the text of the Manifesto.[15] These instructions were reportedly accompanied by a vision of what would occur if the Manifesto were not issued.[15]

Following Woodruff's death in 1898, other church leaders began to teach that the Manifesto was the result of a revelation of God.[34] Since that time, church leaders have consistently taught that the Manifesto was inspired of God.[35][36][37] In 1908, the Manifesto was printed in the LDS Church's Doctrine and Covenants for the first time,[38] and it has been included in every edition since. A non-Mormon observer of the church has stated that "[t]here is no question that, from a doctrinal standpoint, President Woodruff's Manifesto now has comparable status with [Joseph Smith's] revelations in the Doctrine and Covenants."[39] Similarly, another writer has stated bluntly that "contemporary Latter-day Saints regard the Manifesto as a revelation."[38] The Manifesto is currently published as "Official Declaration 1" in the Doctrine and Covenants.[40]

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Lyman, Edward Leo (1994), "Manifesto (Plural Marriage)", Utah History Encyclopedia, University of Utah Press, ISBN 9780874804256, archived from the original on May 30, 2023, retrieved August 15, 2024,

The Manifesto ... affirmed the church president's intention to influence fellow members to obey the law of the land.

- ^ a b c "The Manifesto and the End of Plural Marriage". lds.org. LDS Church. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

The ledger of 'marriages and sealings performed outside the temple,' which is not comprehensive, lists 315 marriages performed between October 17, 1890, and September 8, 1903. Of the 315 marriages recorded in the ledger, research indicates that 25 (7.9%) were plural marriages and 290 were monogamous marriages (92.1%). Almost all the monogamous marriages recorded were performed in Arizona or Mexico. Of the 25 plural marriages, 18 took place in Mexico, 3 in Arizona, 2 in Utah, and 1 each in Colorado and on a boat on the Pacific Ocean.

- ^ Quinn, D. Michael (1985). "LDS Church Authority and New Plural Marriages, 1890–1904". Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought. 18 (1): 9–108. doi:10.2307/45225323. JSTOR 45225323. S2CID 259871046. Archived from the original on September 25, 2015. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

- ^ Hammarberg, Melvyn (2013), The Mormon Quest for Glory: The Religious World of the Latter-Day Saints, New York: Oxford University Press, US, p. 135, ISBN 978-0-19-973762-8.

- ^ David E. Campbell, John C. Green, and J. Quin Monson (2014), Seeking the Promised Land: Mormons and American Politics, New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 58–59, ISBN 978-1107662674.

- ^ "Polygamy: Latter-day Saints and the Practice of Plural Marriage", mormonnewsroom.org.

- ^ a b Krakauer, Jon (2004). Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. pp. 139, 254–255. ISBN 978-1-4000-7899-8.

- ^ 136 U.S. 1 (1890).

- ^ Van Wagoner 1989, p. 135

- ^ Salt Lake Herald, 1889-10-27, quoted in: Van Wagoner 1989, p. 136

- ^ Smith 2005, pp. 62–63

- ^ 133 U.S. 333 (1890).

- ^ Smith 2005, pp. 63–64

- ^ Lyman, Edward Leo (1994), "Manifesto (Plural Marriage)", Utah History Encyclopedia, University of Utah Press, ISBN 9780874804256, archived from the original on May 30, 2023, retrieved August 14, 2024,

After years of determined resistance to governmental pressure to end [polygamy], including test cases in the federal courts, hopes waned of receiving a favorable outcome. The most crucial development was the Davis v. Beason decision in 1890 ... .

- ^ a b c Remarks of Wilford Woodruff at Cache Stake Conference, Logan, Utah, November 1, 1891; reported at Wilford Woodruff, "Remarks", Deseret Weekly (Salt Lake City, Utah) November 14, 1891; excerpts reprinted in LDS Church, "Official Declaration 1", Doctrine and Covenants.

- ^ Burrows, Julius C.; Foraker, Joseph Benson; United States Congress Senate Committee on Privileges and Elections (1906), Proceedings Before the Committee On Privileges and Elections of the United States Senate in the Matter of The Protests Against the Right of Hon. Reed Smoot, a Senator From the State of Utah, To Hold His Seat, 59th Cong., 1st sess. Senate. Doc. 486, vol. II, pp. 52–53, OCLC 4795799

- ^ Wilford Woodruff, "Official Declaration", Deseret Weekly (Salt Lake City) 41:476 (1890-09-25).

- ^ Joseph Stuart (2012). "'For the Temporal Salvation of the Church': Historical Context of the Manifesto, 1882–90". BYU Religious Education Student Symposium, 2012. Religious Studies Center. ISBN 978-0-8425-2829-0. Archived from the original on January 23, 2016. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ a b c Dan Erickson (1998). 'As a Thief in the Night': The Mormon Quest for Millennial Deliverance. Signature Books. p. 205. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ Alexander, Thomas G. (2012). Edward Hunter Snow: Pioneer – Educator – Statesman. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8061-8795-2.

- ^ Kaplan, David A. (2019). The Most Dangerous Branch: Inside the Supreme Court in the Age of Trump. Broadway Books. p. 423. ISBN 978-1-5247-5991-9.

- ^ Pulido, Elisa Eastwood (2020). The Spiritual Evolution of Margarito Bautista: Mexican Mormon Evangelizer, Polygamist Dissident, and Utopian Founder, 1878–1961. Oxford University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-19-094212-0.

- ^ a b c LDS Church, Official Declaration 1, Doctrine and Covenants.

- ^ Diary entry of Marriner W. Merrill, 1890-10-06 (LDS Church archives), as cited in: Hardy 1992, p. 141.

- ^ Lorenzo Snow, who would succeed Woodruff as president of the church, was one such leader.

- ^ Cannon, Kenneth L. II (1978), "Beyond the Manifesto: Polygamous Cohabitation among LDS General Authorities after 1890", Utah Historical Quarterly, 46 (1): 24–36, doi:10.2307/45060569, JSTOR 45060569, S2CID 254447400, archived from the original on October 21, 2013, retrieved January 16, 2014

- ^ Flake, Kathleen (2003), The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 0-8078-5501-4, OCLC 57707347

- ^ Numerous marriages also were performed in international waters on the high seas.

- ^ Hardy 1992, pp. 167–335 and appendix II

- ^ "Plural Marriage and Families in Early Utah", churchofjesuschrist.org.

- ^ Jorgensen, Victor W.; Hardy, B. Carmon (1980), "The Taylor-Cowley Affair and the Watershed of Mormon History", Utah Historical Quarterly, 48 (1): 4, doi:10.2307/45060923, JSTOR 45060923, S2CID 254444205, archived from the original on October 21, 2013, retrieved January 16, 2014.

- ^ Handbook 1: Stake Presidents and Bishops, Salt Lake City: LDS Church, 2010, p. 57.

- ^ Hardy 1992, pp. 146–152

- ^ See, e.g., Discourse delivered by Lorenzo Snow at St. George, Utah, on 1899-05-03, published as Lorenzo Snow, "Discourse" Archived 2007-10-25 at the Wayback Machine, Millennial Star, vol. 61, no. 34 pp. 529–533 at p. 532 (1899-08-24), reprinted in Lorenzo Snow (1998, Clyde J. Williams ed.). The Teachings of Lorenzo Snow: Fifth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft) pp. 192–193.

- ^ Widtsoe, John A. (1943), Evidences and Reconciliations: Aids to Faith in a Modern Day, Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, p. 89, OCLC 36111479.

- ^ Smith, Joseph Fielding (1971) [1922], Essentials in Church History: A History of the Church from the Birth of Joseph Smith to the Present Time (24th ed.), Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, pp. 493–494, OCLC 48064256.

- ^ Kimball, Spencer W. (1998) [1982], Kimball, Edward L. (ed.), The Teachings of Spencer W. Kimball: Twelfth President of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah: Bookcraft, pp. 447–448, ISBN 1-57008-484-X, OCLC 39304039.

- ^ a b Turner, John G. (2016), The Mormon Jesus: A Biography, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, p. 91, ISBN 978-0-674-73743-3.

- ^ Shipps, Jan (1985), Mormonism: The Story of a New Religious Tradition, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, p. 114, ISBN 0-252-01159-7, OCLC 10726560.

- ^ Brzuzy, Stephanie; Lind, Amy (2007). Battleground: Women, Gender, and Sexuality [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 418. ISBN 978-0-313-08800-1.

General references

[edit]- Hardy, B. Carmon (1992), Solemn Covenant: The Mormon Polygamous Passage, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, ISBN 0-252-01833-8, OCLC 23219530

- Quinn, D. Michael (1997), The Mormon Hierarchy: Extensions of Power, Salt Lake City: Signature Books, ISBN 1-56085-060-4, OCLC 32168110, archived from the original on October 30, 2005

- Smith, Stephen Eliot (2005), The 'Mormon Question' Revisited: Anti-polygamy Laws and the Free Exercise Clause (LL.M thesis), Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Law School, OCLC 70120125

- Van Wagoner, Richard S. (1989), Mormon Polygamy: A History (2nd ed.), Salt Lake City: Signature Books, ISBN 0-941214-79-6, OCLC 19515803

Further reading

[edit]- Peterson, Paul H. (1992), "Manifesto of 1890", in Ludlow, Daniel H (ed.), Encyclopedia of Mormonism, New York: Macmillan Publishing, pp. 852–853, ISBN 0-02-879602-0, OCLC 24502140

External links

[edit]- Official Declaration 1: Full text of the Manifesto and other background statements from LDS Church Doctrine and Covenants

- Plural Marriages After The 1890 Manifesto – essay by Quinn

- 1890 in Christianity

- 1890 in the United States

- 1890 documents

- Latter Day Saint statements of faith

- Doctrine and Covenants

- History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Manifestos

- Mormon fundamentalism

- Works originally published in the Deseret News

- Works about polygamy in Mormonism

- Works by presidents of the church (LDS Church)

- Marriage in Utah