Carotid artery stenosis

| Carotid artery stenosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | TIA - carotid artery[1] |

| |

| Carotid artery disease | |

| Specialty | Vascular surgery |

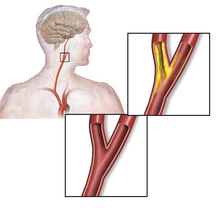

Carotid artery stenosis is a narrowing or constriction of any part of the carotid arteries, usually caused by atherosclerosis.[2]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]The common carotid artery is the large artery whose pulse can be felt on both sides of the neck under the jaw. On the right side it starts from the brachiocephalic artery (a branch of the aorta), and on the left side the artery comes directly off the aortic arch. At the throat it forks into the internal carotid artery and the external carotid artery. The internal carotid artery supplies the brain, and the external carotid artery supplies the face. This fork is a common site for atherosclerosis, an inflammatory build-up of atheromatous plaque inside the common carotid artery, or the internal carotid arteries that causes them to narrow.[3][4]

The plaque can be stable and asymptomatic, or it can be a source of embolization. Emboli break off from the plaque and travel through the circulation to blood vessels in the brain. As the vessels get smaller, an embolus can lodge in the vessel wall and restrict the blood flow to parts of the brain. This ischemia can either be temporary, yielding a transient ischemic attack (TIA), or permanent resulting in a thromboembolic stroke.[5]

Transient ischemic attacks are a warning sign and may be followed by severe permanent strokes, particularly within the first two days. TIAs by definition last less than 24 hours and frequently take the form of weakness or loss of sensation of a limb or the trunk on one side of the body or the loss of sight (amaurosis fugax) in one eye. Less common symptoms are artery sounds (bruits), or ringing in the ears (tinnitus).[6]

In asymptomatic individuals with a carotid stenosis, the risk of developing a stroke is increased above those without a stenosis. The risk of stroke is possibly related to the degree of stenosis on imaging. Some studies have found an increased risk with increasing degrees of stenosis[7] while other studies have not been able to find such a relationship.[8]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Atherosclerosis causes plaque to form within the carotid artery walls, usually at the fork where the common carotid artery divides into the internal and external carotid artery. The plaque build-up can narrow or constrict the artery lumen, a condition called stenosis. Rupture of the plaque can release atherosclerotic debris or blood clots into the artery. A piece of this material can break off and travel (embolize) up through the internal carotid artery into the brain, where it blocks circulation, and can cause death of the brain tissue, a condition referred to as ischemic stroke.[9]

Sometimes the stenosis causes temporary symptoms first, known as TIAs, where temporary ischemia occurs in the brain, or retina without causing an infarction.[10] Symptomatic stenosis has a high risk of stroke within the next 2 days. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend that people with moderate to severe (50–99% blockage) stenosis, and symptoms, should have "urgent" endarterectomy within 2 weeks.[11]

When the plaque does not cause symptoms, people are still at higher risk of stroke than the general population, but not as high as people with symptomatic stenosis. The incidence of stroke, including fatal stroke, is 1–2% per year. The surgical mortality of endarterectomy ranges from 1–2% to as much as 10%. Two large randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that carotid surgery done with a 30-day stroke and death risk of 3% or less will benefit asymptomatic people with ≥60% stenosis who are expected to live at least 5 years after surgery.[12][13] Surgeons are divided over whether asymptomatic people should be treated with medication alone or should have surgery.[14][15]

The common carotid artery is the large vertical artery in red. The blood supply to the carotid artery starts at the arch of the aorta (bottom). The carotid artery divides into the internal carotid artery and the external carotid artery. The internal carotid artery supplies the brain. Plaque often builds up at that division and causes a narrowing (stenosis). Pieces of plaque can break off and block the small arteries above in the brain, which causes a stroke. Plaque can also build up at the origin of the carotid artery at the aorta.[citation needed]

-

Section of carotid artery with plaque. Blood flows from the common carotid artery(bottom), and divides into the internal carotid artery (left) and external carotid artery (right). The atherosclerotic plaque is the dark mass on the left

Diagnosis

[edit]

Carotid artery stenosis is usually diagnosed by color flow duplex ultrasound scan of the carotid arteries in the neck. This involves no radiation, no needles and no contrast agents that may cause allergic reactions. This test has good sensitivity and specificity.[16]

Typically duplex ultrasound scan is the only investigation required for decision making in carotid stenosis as it is widely available and rapidly performed. However, further imaging can be required if the stenosis is not near the bifurcation of the carotid artery.[17]

One of several different imaging modalities, such as a computed tomography angiogram (CTA)[18][19][20] or magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) may be useful. Each imaging modality has its advantages and disadvantages - Magnetic resonance angiography and CT angiography with contrast is contraindicated in patients with chronic kidney disease, catheter angiography has a 0.5% to 1.0% risk of stroke, MI, arterial injury or retroperitoneal bleeding. The investigation chosen will depend on the clinical question and the imaging expertise, experience and equipment available.[21]

Based on the NASCET (The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial) criteria, the degree of carotid stenosis is defined as:[22]

- percent stenosis = ( 1 − ( minimum diameter within stenosis) / ( poststenotic diameter ) ) × 100%.

Calculators have been developed to facilitate grading of carotid stenosis per NASCET criteria.[23]

Screening

[edit]The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends against routine screening for carotid artery stenosis in those without symptoms as of 2021.[24]

While routine population screening is not advised, the American Heart Association[25] and the Society for Vascular Surgery[26] recommend screening in those diagnosed with related medical conditions or have risk factors for carotid artery disease.[27] Screening is recommended for people who have:[citation needed]

- Vascular disease elsewhere in the body, including:

- Peripheral artery disease (PAD)

- Coronary artery disease (CAD)

- Atherosclerotic aortic aneurysm (AAA)

- Two or more of the following risk factors:

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- High cholesterol (hyperlipidemia)

- Tobacco smoking

- Family history – First-degree relative diagnosed with atherosclerosis before age 60 or who had an ischemic stroke

The American Heart Association also recommends screening if a physician detects a carotid bruit, or murmur, over the carotid artery by listening through a stethoscope during a physical exam. For people with symptoms, the American Heart Association recommends initial screening using ultrasound.[citation needed]

Treatment

[edit]The goal of treating carotid artery stenosis is to reduce the risk of stroke. The type of treatment depends on the severity of the disease and includes:[citation needed]

- Lifestyle modifications including smoking cessation, eating a healthy diet and reducing sodium intake, losing weight, and exercising regularly.

- Medications to control high blood pressure and high levels of lipids in the blood.

- Surgical intervention for carotid artery revascularization.

Medication

[edit]Clinical guidelines (such as those of the American Heart Association (AHA)[28] and National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE)[29]) recommend that all patients with carotid stenosis be given medications to control their vascular risk factors, usually blood pressure lowering medications (if they have hypertension), diabetes medication (if they have diabetes), and recommend exercise, weight reduction (if overweight) and smoking cessation (for smokers). In addition, they would benefit from anti-platelet medications (such as aspirin or clopidogrel) and cholesterol lowering medication (such as statins, which were originally prescribed for their cholesterol-lowering effects but were also found to reduce inflammation and stabilize plaque).[citation needed]

Revascularization

[edit]According to the American Heart Association, interventions beyond medical management is based upon whether patients have symptoms:[citation needed]

- Asymptomatic patients: severity of carotid artery stenosis, assessment of other medical conditions, life expectancy, and other individual factors; evaluation of the risks versus benefits; and patient preference are considered when determining whether surgical intervention should be performed.

- Symptomatic patients: it is recommended by the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association that patients who have experienced a transient ischemic attack or non-severely disabling acute ischemic stroke undergo surgical intervention, if possible.[30][31]

All interventions for carotid revascularization (carotid endarterectomy, carotid stenting, and transcarotid artery revascularization) carry some risk of stroke; however, where the risk of stroke over time from medical management alone is high, intervention may be beneficial. Carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy have been found to have similar benefits in patients with severe degree of carotid artery stenosis.[32][33]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Carotid artery disease: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia". medlineplus.gov. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- ^ "Atherosclerosis". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Ashrafian H (March 2007). "Anatomically specific clinical examination of the carotid arterial tree". Anatomical Science International. 82 (1): 16–23. doi:10.1111/j.1447-073X.2006.00152.x. PMID 17370446. S2CID 12109379.

- ^ Manbachi A, Hoi Y, Wasserman BA, Lakatta EG, Steinman DA (December 2011). "On the shape of the common carotid artery with implications for blood velocity profiles". Physiological Measurement. 32 (12): 1885–97. doi:10.1088/0967-3334/32/12/001. PMC 3494738. PMID 22031538.

- ^ Easton, J. Donald; Saver, Jeffrey L.; Albers, Gregory W.; Alberts, Mark J.; Chaturvedi, Seemant; Feldmann, Edward; Hatsukami, Thomas S.; Higashida, Randall T.; Johnston, S. Claiborne; Kidwell, Chelsea S.; Lutsep, Helmi L.; Miller, Elaine; Sacco, Ralph L.; American Heart Association; American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease (June 2009). "Definition and Evaluation of Transient Ischemic Attack: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists". Stroke. 40 (6): 2276–2293. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218. PMID 19423857.

- ^ Easton, J. Donald; Saver, Jeffrey L.; Albers, Gregory W.; Alberts, Mark J.; Chaturvedi, Seemant; Feldmann, Edward; Hatsukami, Thomas S.; Higashida, Randall T.; Johnston, S. Claiborne; Kidwell, Chelsea S.; Lutsep, Helmi L.; Miller, Elaine; Sacco, Ralph L.; American Heart Association; American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease (June 2009). "Definition and Evaluation of Transient Ischemic Attack: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists". Stroke. 40 (6): 2276–2293. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218. PMID 19423857.

- ^ Howard, Dominic P J; Gaziano, Liam; Rothwell, Peter M (March 2021). "Risk of stroke in relation to degree of asymptomatic carotid stenosis: a population-based cohort study, systematic review, and meta-analysis". The Lancet Neurology. 20 (3): 193–202. doi:10.1016/s1474-4422(20)30484-1. ISSN 1474-4422. PMC 7889579. PMID 33609477.

- ^ den Hartog, Anne G.; Achterberg, Sefanja; Moll, Frans L.; Kappelle, L. Jaap; Visseren, Frank L.J.; van der Graaf, Yolanda; Algra, Ale; de Borst, Gert Jan (April 2013). "Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis and the Risk of Ischemic Stroke According to Subtype in Patients With Clinical Manifest Arterial Disease". Stroke. 44 (4): 1002–1007. doi:10.1161/strokeaha.111.669267. ISSN 0039-2499. PMID 23404720. S2CID 7567725.

- ^ "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Atherosclerosis? - NHLBI, NIH". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. 22 June 2016. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Easton, J. D.; Saver, J. L.; Albers, G. W.; Alberts, M. J.; Chaturvedi, S.; Feldmann, E.; et al. (2009). "Definition and Evaluation of Transient Ischemic Attack: A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease: The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists". Stroke. 40 (6): 2276–2293. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.192218. ISSN 0039-2499. PMID 19423857.

- ^ Swain S, Turner C, Tyrrell P, Rudd A (July 2008). "Diagnosis and initial management of acute stroke and transient ischaemic attack: summary of NICE guidance". BMJ. 337: a786. doi:10.1136/bmj.a786. PMID 18653633. S2CID 19624935.

- ^ Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study (ACAS) (1995). "Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis". JAMA. 273 (18): 1421–1428. doi:10.1001/jama.273.18.1421.

- ^ Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, Peto C, Peto R, Potter J, Thomas D (2004). "Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial". Lancet. 363 (9420): 1491–1502. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(04)16146-1. PMID 15135594. S2CID 22814764.

- ^ Sila CA, Higashida RT, Clagett GP (April 2008). "Clinical decisions. Management of carotid stenosis". N. Engl. J. Med. 358 (15): 1617–21. doi:10.1056/NEJMclde0800741. PMID 18403770.

- ^ Drug Therapy Gains Favor to Avert Stroke, By THOMAS M. BURTON, Wall Street Journal, MARCH 3, 2009. Layman's summary of surgery vs. medication-only debate.

- ^ Jahromi, AS; Cinà, CS; Liu, Y; Clase, CM (June 2005). "Sensitivity and specificity of color duplex ultrasound measurement in the estimation of internal carotid artery stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 41 (6): 962–72. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2005.02.044. PMID 15944595.

- ^ Saxena, A; Yin Kwee, E; Lim, S (2019). "Imaging modalities to diagnose carotid artery stenosis: progress and prospect". BioMedical Engineering OnLine. 18 (1): 66. doi:10.1186/s12938-019-0685-7. PMC 6537161. PMID 31138235. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Bartlett ES, Walters TD, Symons SP, Fox AJ (January 2006). "Quantification of carotid stenosis on CT angiography". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 27 (1): 13–19. PMC 7976065. PMID 16418349.

- ^ White JH, Bartlett ES, Bharatha A, Aviv RI, Fox AJ, Thompson AL, Bitar R, Symons SP (July 2010). "Reproducibility of semi-automated measurement of carotid stenosis on CTA". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 37 (4): 498–503. doi:10.1017/s0317167100010532. PMID 20724259.

- ^ Lian K, White JH, Bartlett ES, Bharatha A, Aviv RI, Fox AJ, Symons SP (May 2012). "NASCET percent stenosis semi-automated versus manual measurement on CTA". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 39 (3): 343–6. doi:10.1017/s0317167100013482. PMID 22547515.

- ^ Solomon, Caren G.; Grotta, James C. (19 September 2013). "Carotid Stenosis". New England Journal of Medicine. 369 (12): 1143–1150. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1214999. PMID 24047063.

- ^ Ferguson, Gary G.; Eliasziw, Michael; Barr, Hugh W. K.; Clagett, G. Patrick; Barnes, Robert W.; Wallace, M. Christopher; Taylor, D. Wayne; Haynes, R. Brian; Finan, Jane W.; Hachinski, Vladimir C.; Barnett, Henry J. M. (September 1999). "The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial: Surgical Results in 1415 Patients". Stroke. 30 (9): 1751–1758. doi:10.1161/01.STR.30.9.1751. ISSN 0039-2499.

- ^ "ECST & NASCET Calculator for Carotid Stenosis". Rad At Hand. Retrieved 2024-07-17.

- ^ US Preventive Services Task, Force.; Krist, AH; Davidson, KW; Mangione, CM; Barry, MJ; Cabana, M; Caughey, AB; Donahue, K; Doubeni, CA; Epling JW, Jr; Kubik, M; Ogedegbe, G; Pbert, L; Silverstein, M; Simon, MA; Tseng, CW; Wong, JB (2 February 2021). "Screening for Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement". JAMA. 325 (5): 476–481. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.26988. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 33528542.

- ^ Brott, Thomas G.; Halperin, Jonathan L.; Abbara, Suhny; Bacharach, J. Michael; Barr, John D.; Bush, Ruth L.; Cates, Christopher U.; Creager, Mark A.; Fowler, Susan B.; Friday, Gary; Hertzberg, Vicki S. (2011-07-26). "2011 ASA/ACCF/AHA/AANN/AANS/ACR/ASNR/CNS/SAIP/SCAI/SIR/SNIS/SVM/SVS Guideline on the Management of Patients With Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Stroke Association, American Association of Neuroscience Nurses, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, American College of Radiology, American Society of Neuroradiology, Congress of Neurological Surgeons, Society of Atherosclerosis Imaging and Prevention, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of NeuroInterventional Surgery, Society for Vascular Medicine, and Society for Vascular Surgery". Circulation. 124 (4): 489–532. doi:10.1161/CIR.0b013e31820d8d78. ISSN 0009-7322. PMID 21282505.

- ^ Ricotta, John J.; AbuRahma, Ali; Ascher, Enrico; Eskandari, Mark; Faries, Peter; Lal, Brajesh K. (September 2011). "Updated Society for Vascular Surgery guidelines for management of extracranial carotid disease: Executive summary". Journal of Vascular Surgery. 54 (3): 832–836. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2011.07.004. ISSN 0741-5214. PMID 21889705.

- ^ "Guideline on the Management of Patients With Extracranial Carotid and Vertebral Artery Disease" (PDF). American Heart Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-11-17. Retrieved 2018-08-22.

- ^ Archived copy Archived 2017-11-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Carotid Artery Stenosis information. Internal carotis occlusion". patient.info. Retrieved 2018-10-08.

- ^ Barnett, H. J.; Taylor, D. W.; Eliasziw, M.; Fox, A. J.; Ferguson, G. G.; Haynes, R. B.; Rankin, R. N.; Clagett, G. P.; Hachinski, V. C.; Sackett, D. L.; Thorpe, K. E.; Meldrum, H. E.; Spence, J. D. (1998-11-12). "Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators". The New England Journal of Medicine. 339 (20): 1415–1425. doi:10.1056/NEJM199811123392002. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 9811916.

- ^ Kleindorfer, Dawn O.; Towfighi, Amytis; Chaturvedi, Seemant; Cockroft, Kevin M.; Gutierrez, Jose; Lombardi-Hill, Debbie; Kamel, Hooman; Kernan, Walter N.; Kittner, Steven J.; Leira, Enrique C.; Lennon, Olive; Meschia, James F.; Nguyen, Thanh N.; Pollak, Peter M.; Santangeli, Pasquale (July 2021). "2021 Guideline for the Prevention of Stroke in Patients With Stroke and Transient Ischemic Attack: A Guideline From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association". Stroke. 52 (7): e364–e467. doi:10.1161/STR.0000000000000375. ISSN 1524-4628. PMID 34024117. S2CID 235169226.

- ^ Halliday, Alison; Bulbulia, Richard; Bonati, Leo H.; Chester, Johanna; Cradduck-Bamford, Andrea; Peto, Richard; Pan, Hongchao; ACST-2 Collaborative Group (2021-09-18). "Second asymptomatic carotid surgery trial (ACST-2): a randomised comparison of carotid artery stenting versus carotid endarterectomy". Lancet. 398 (10305): 1065–1073. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01910-3. ISSN 1474-547X. PMC 8473558. PMID 34469763.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Mott, Meghan; Koroshetz, Walter; Wright, Clinton B. (May 2017). "CREST-2: Identifying the Best Method of Stroke Prevention for Carotid Artery Stenosis: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Organizational Update". Stroke. 48 (5): e130–e131. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.016051. ISSN 1524-4628. PMC 5467643. PMID 28386040.