Zashiki Hakkei

Zashiki Hakkei (Japanese: 坐敷八景,[a] "Eight Parlour Views") is a series of eight prints from 1766[2] by the Japanese ukiyo-e artist Suzuki Harunobu. They were the first full-colour nishiki-e prints and are considered representative examples of Harunobu's work. The prints are mitate-e parodies of popular themes of the 11th-century Chinese landscape painting series, Eight Views of Xiaoxiang; Harunobu replaces natural scenery with domestic scenes.

Harunobu made an erotic shunga version of the series in c. 1768–70 called Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei (風流座敷八景, "Eight Fashionable Parlour Views" or "Eight Modern Parlour Views"), each accompanied with a poem. He appropriated images and poetry for them from works by earlier artists, particularly those of the artist Nishikawa Sukenobu (1671–1750) and the poet Fukuo Kichijirō.

The Zashiki Hakkei theme became popular with artists such as Torii Kiyonaga, who produced two series based on Harunobu's Zashiki Hakkei in the late 1770s, and Isoda Koryūsai, who produced a Zashiki Hakkei series of his own.

Background

[edit]Ukiyo-e emerged in Japan as a genre of paintings and woodblock prints in the late 17th century.[3] Early prints were printed with black ink; colour was sometimes added by hand, and by the mid-18th century with extra woodblocks.[4] Suzuki Harunobu (1725–1770) achieved fame in the latter 1760s for his pioneering nishiki-e "brocade prints" made with a large number of coloured blocks.[5] These arose at a daishōkai[b] calendar-picture printing event hosted in 1765 by Ōkubo Kyosen,[6] a hatamoto samurai who produced haiku poetry and ukiyo-e art.[7] The prolific Harunobu became the dominant ukiyo-e artist of his time.[8] He made these prints typically on commission, and they bore the name of the patron rather than the artist on first printings; later printings for the public removed the patron's name or replaced it with the artist's.[9]

The Eight Views of Xiaoxiang is a Chinese series of eight shan shui "mountain-water" paintings of views of the Xiao and Xiang Rivers in China.[7] The scholar-painter Song Di produced the first rendition in the 1060s with a series of landscape handscrolls, to which he later attached a one-line poem to each. The theme soon became a popular subject in artistic circles.[10] It later became a popular theme with Japanese bunjin literati painters[7] and became widely known after its introduction in Japan during the Muromachi period (1336–1573). Thereafter the subjects and titles formed the basis for paintings and poetry.[11] The Japanese often adapted the theme to local geography, with such titles as Eight Views of Edo or Eight Views of Kanagawa. One of the earliest and most popular of these localized themes was Eight Views of Ōmi, set in Ōmi Province (modern Shiga Prefecture), which surrounds Lake Biwa, not far from the ancient capital of Kyoto.[12]

Harunobu often employed numerous complex mitate allusions in his prints for viewers to take pleasure in recognizing and deciphering.[13] Early in his career he made a Ōmi Hakkei no Uchi[c] series of vertical hashira-e "pillar prints".[14]

Publication

[edit]

The series appeared in chūban size[d][15] from the publisher Shokakudō[e] of Yokoyama-chō in Edo (modern Tokyo)[16] in c. 1766.[f] As was common at the time, the higher-quality first printing of the series bore the seal of the client who commissioned it:[2] Kyosen (巨川), for Ōkubo Kyosen.[7] Kyosen distributed some of the print sets,[16] which came in an expensive paulownia box[17] in which a packet wrapping the prints displayed Harunobu's name and the titles of the prints, which did not appear on the prints themselves in this printing.[g][16]

Shōkakudō republished the prints for the general public with Harunobu's name on the wrapper, on which it advertised the new full-colour technique as Azuma nishiki-e[18] ("brocade pictures of the Eastern Capital"—"Azuma" refers to the country's administrative capital Edo, found in eastern Japan).[19] The publisher sold this edition of the set without Kyosen's seal,[18] and with an index sheet listing the names of the prints.[20] The publisher sold the prints individually without a wrapper from the third printing on with Harunobu's seal on them. Later printings appeared from other publishers as well, some of the full set, others of individual prints, sometimes with certain prints reused in other series.[18]

Art historians have traced major compositional elements in Harunobu's work to earlier works by artists such as Nishikawa Sukenobu (1671–1750), Okumura Masanobu (1686–1764), Ishikawa Toyonobu.[21] Harunobu's appropriations are so close in detail to the originals that he appears not to have tried to hide them.[22] Art historian Akiko Tanabe considered this a deliberate approach demonstrating Harunobu's appreciation of the traditional themes of his art.[21]

Harunobu produced an erotic shunga version of the series in c. 1768–70[h] titled Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei "Eight Fashionable Parlour Views" or "Eight Modern Parlour Views").[15] These were also in chūban size,[23] and were likely sold separately, whereas the original Zashiki Hakkei was sold at first as a bundle.[25] Art historians did not have access to a complete set of Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei until 1994. Tadashi Kobayashi published the first study of the complete in 1999. Monta Hayakawa provided an in-depth interpretation of mitate elements in them in a book on Harunobu's use of mitate in 2002.[26]

It is thought that Kyosen had the prints based on kyōka poems by Fukuo Kichijirō[i] and Nagata Teiryū[j] (1654–1734);[28] both had produced sets of poems on the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang, Teiryū in c. 1722 and Kichijirō in c. 1725.[15] Kyosen and Harunobu were almost certainly familiar with their work, and the poems on the Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei prints bear a close resemblance to Kichijirō's.[28] Kichijirō, from Owari Province, put his humorous Zashiki Hakkei in domestic settings. He was an adolescent[29] when his series appeared in the Kyōhō Sesetsu,[k] a collection of poetry assembled in the Kyōhō era (1716–36). The Kyōhō Sesetsu exists only in hand-written manuscript copies, amongst which there may have been small differences.[15] Because not one of Harunobu's is precisely the same as known copies of Kichijirō's, it is likely they were based on Kichijirō's with changes made. It is possible they came from a copy of the manuscript unknown to scholars, but differences in known copies are slight.[15]

Harunobu re-used compositional elements from the series in other prints, as did other artists.[30] There is a series on the four seasons that uses rearranged visual elements from Zashiki Hakkei with the poems from Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei attached; it is signed "Harunobu" but is likely the work of Shiba Kōkan, who signed many of his works with Harunobu's name. In c. 1777[31] Torii Kiyonaga (1752–1815) produced two of his own versions of Harunobu's Zashiki Hakkei under the titles Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei (1777) and Zashiki Hakkei Mono (1778),[32] to both of which he added the poems from Harunobu's Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei.[33] Kiyonaga's versions modernize the styles of the hair and kimonos[34] and rearrange the figures and viewpoints of Harunobu's originals.[33]

Zashiki Hakkei has come to be seen as a representative example of Harunobu's work.[18] The art scholar Monta Hayakawa considers Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei likely the most complex set of shunga prints.[35]

Description and analysis

[edit]With the exception of Clearing Mist of the Fan, the prints depict indoor scenes set in a zashiki—a Japanese-style room floored with tatami straw mats. Two women feature in each print of Zashiki Hakkei, and each is a mitate parody that alludes to the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang series, replacing the landscape scenery of the paintings with contemporary domestic scenes and objects.[18]

Aside from the erotic content, Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei differs most from Zashiki Hakkei by the addition of a kyōka poem to each print,[36] set off from the rest of the picture with wavy, cloud-like lines.[25] The mitate works on two levels: as a parody of the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang replacing natural scenery with domestic furnishings, and by adding a male–female tale to the eight views.[36]

Kotoji no rakugan

[edit]-

Second state, with no seal

-

From the third state, bearing Harunobu's seal: 春信

-

Erotic Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version; the hairstyle and clothing indicate the rear figure is male

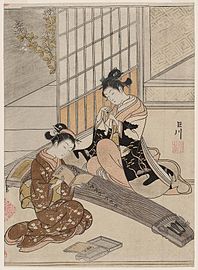

Kotoji no rakugan (琴柱の落雁, "Descending geese of the koto bridges") parodies Wild Geese Descending on a Sandbank (平沙落雁 Heisa rakugan),[37] which traditionally depicts a flock of geese descends on the banks of the Xiang River.[38] The title poses translation difficulties. Common translations include Descending Geese of the Koto Bridges and Descending Geese of the Koto Bridges, suggesting geese landing on the bridges of the koto. A more word-for-word translation as The Koto Bridges' Descending Geese reveals ambiguity in the original title: it may also refer to geese landing on the bridges, or to the bridges representing the geese themselves.[39]

The scene depicts a young girl from a privileged family practising the koto,[40] an instrument with movable bridges for each of its 13 strings.[41] The diagonal arrangement of bridges suggests a skein of geese across the broad paulownia-wood surface like a sandbank in allusion to Kotoji no rakugan; the pine-strewn beach design of the girl's long-sleeved kimono reinforces the allusion. The Japanese clovers that peek out from behind the shōji sliding door indicate the scene takes place in autumn.[40]

The girl in the foreground holds a koto training songbook, and another lies on the floor.[42] They are titled Kinkyokushū[l] and are in the same format as the two-volume Kinkyokushō[m] collection of kumi-uta pieces for the koto published c. 1764–65.[43] Such songbooks typically opened with "Fuki",[n] a piece by the priest Kenjun that is considered the first of the kumi-uta genre.[42] Contemporary viewers of the print would have been familiar with the piece and its third verse:[44]

| Japanese text | Romanized Japanese[45] | English translation[46][o] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version, titled 琴柱落雁, was the first in the series, which is thus perhaps why it is quieter and less explicit than the rest. In the print a young girl plays the koto while receiving a kiss from behind from a young male,[47] who is untying her obi sash.[48] The uncut forelocks of the male indicate a wakashū—a boy who has not yet had his genpuku coming-of-age ceremony,[47] which at the time would have taken place when he reached 15 or 16.[49] The changing colours of the leaves outside the window suggest indicate autumn, the season of migrating geese of Kotoji no rakugan, a version of which appears on a partitioning screen behind the pair. Further allusions include those relating to the koto, as in the original version of the print,[47] and the painting of a skein of geese on the partitioning screen at right behind the boy.[48] To the right a black dog appears to feign disinterest in its owner's lovemaking.[50]

| Japanese text[47] | Romanized Japanese | English translation[51][p] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The mitate works on two main levels: first, replacing the traditional natural setting with a modern domestic one; and second, replacing the geese imagery with a scene of young love.[52] Hayakawa finds mitate allusions in the poem that relate to the image: he sees the "first geese" signifying the boy's first love, and the sound of the koto—an instrument that most often young women learn—representing the awakening of the girl's romantic feelings. He sees the reddening Japanese maple leaves reflecting the girl's growing passion for the boy and the pattern of maple and Japanese ivy leaves on her sleeves representing her sensuality.[49] Ishigami notes that Kichijirō's version of the poem emphasizes the shape of the descending skein of geese,[q] while Harunobu's emphasizes the sound of the koto attracting the geese, an image on which Harunobu builds a visual allusion in the picture.[48]

Ōgi no seiran

[edit]-

Ōgi no seiran, 1766

-

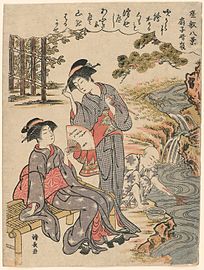

Geisha and Assistant in Front of the Matsumotoya, c. 1767–68

-

Geisha and Attendant on Riverbank, c. 1768–70

-

Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version of Clearing Mist of the Fan, 1769

-

Mountain Village, Clearing Mist version by Kanō Tan'yū, 17th century

Ōgi no seiran (扇の清嵐, "Clearing mist of the fan") parodies Mountain Village, Clearing Mist (山市晴嵐 Sanshi seiran).[37]

The print depicts a young girl in a kimono with flowing long sleeves at a street corner ōgi folding hand fan[r] while leading another girl, who turns her head away from the first, perhaps against the wind that clears the mist. The first girl appears to shield herself from the sun, which suggests the summer scene of Mountain Village, Clearing Mist.[53]

The erotic Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version takes place at a hand-fan seller's machiya home; lacquered boxes for illustrated hand fans lay on the floor, as does a yet-unset printed fan sheet of a tiger amongst bamboo trees. At the time the custom was to change fan sheets in early summer.[50] To the left an aproned child amuses itself catching goldfish.[25] Yoshikazu Hayashi dates the series to 1770 based on the tiger design on the fan, which he says suggests the year of the tiger in the Chinese zodiac—though other sources maintain a publishing date of c. 1768–69.[24]

Before he began to produce full-colour prints, Harunobu used the same composition in a benizuri-e print, Before the Tomiyoshi-ya,[s] in which the lead figure carries a closed umbrella rather than a fan while passing before the Tomiyoshi-ya liquor store.[54] Harunobu later reused the composition in other prints, such as In Front of the Matsumotoya[t] (c. 1767–68) and Geisha and Attendant on Riverbank[u] (c. 1768–69),[30] the latter of which also reuses the poem from the Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version.[55]

| Japanese text[50] | Romanized Japanese | English translation[56][p] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Nurioke no bosetsu

[edit]-

Nurioke no bosetsu, 1766

-

Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version, 1769

-

From Nure-sugata Aizomekawa, Nishikawa Sukenobu, 1722

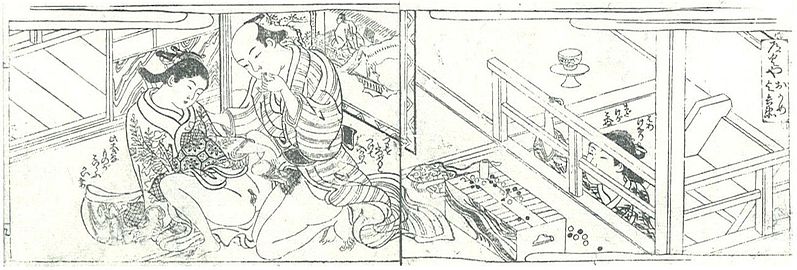

Nurioke no bosetsu (塗桶の暮雪 "Evening snow on the nurioke") parodies River and Sky in Evening Snow (江天暮雪 Kōten bosetsu).[37] While kōten (江天, "large river and sky") implies a composition in which a broad skyline lies against a wide river, the renderings in the Eight Views of Xiaoxiang tend to emphasize the snow-covered mountains. Harunobu replaces these mountains with nurioke, lacquered wooden forms that silk floss was placed on to dry.[57] The young man at the top helps the young woman at the bottom prepare wadding from white silk floss.[16] The print's embossing gives the feeling of the softness of the silk floss detail, a technique called karazuri (空摺り) that uses an un-inked woodblock.[58]

The erotic Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version is of a cotton worker having sex with a clerk who has come to collect goods. The clerk's account book lies behind him to the right, and the print employs the same nurioke allusion to the mountains of River and Sky in Evening Snow. At the time this cotton work was understood as typically a front for women who also worked as prostitutes.[59] Outside the shōji in the background appear the head and forelegs of a white dog whose arched posture suggest a female in mid-copulation. Harunobu employs a range of contrasts—white cloth on black nurioke, public work and private, male and female—from which Hayakawa surmises the unseen male dog must be black, stating that such calling forth of the imagination was one of the pleasures of mitate for contemporary viewers.[60] Harunobu appears to have appropriated the positioning and gestures of the copulating figures from the ninth page of Sukenobu's Nure-sugata Aizomekawa[v] of 1722 for the Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei.[61]

| Japanese text[59] | Romanized Japanese | English translation[62][p] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Tokei no banshō

[edit]-

Tokei no banshō, 1766

-

Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version, 1768–70

-

Shōkei's version of Evening Gong at Qingliang Temple, early 16th century

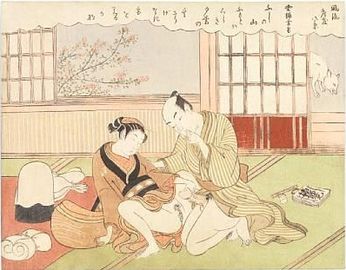

Tokei no banshō (時計の晩鐘, "Evening Bell of the Clock") parodies Evening Gong at Qingliang Temple (烟寺晩鐘 Enji banshō).[37]

The print depicts the proprietress of a bathhouse relaxing on the veranda outside the baths. A female servant attends to her while looking back at a Japanese clock inside. The indicates the evening hour, alluding to the evening gong, and sits upon a tall stand, alluding to the mountain Qingliang Temple sits upon.[63]

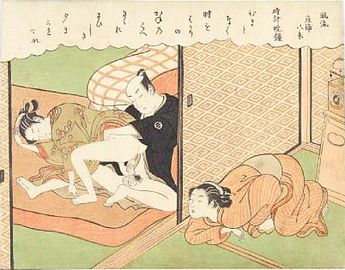

In the Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version a female servant peeps from behind a fusuma sliding door at a man and woman having sex, a common theme in Harunobu's shunga prints as typified in his Maneemon series. As in the original, a clock at the far right edge alludes to the gong in The Evening Gong at Qingliang Temple. The clock and the thick bedding were costly items at the time and indicate the home of a wealthy merchant.[64] The composition and the poem about "becoming extremely lonely" draws attention to the servant, rather than the copulating couple as would be expected in an erotic print.[65]

Harunobu appears to have combined images from two e-hon for the composition of Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei. The copulating pair share the positioning of a couple in the final volume of Sukenobu's Furyū Iro Hakkei[w] of 1715, and Harunobu appears to have appropriated the peeping servant from the anonymous Nanshoku Yamaji no Tsuyu[x] of c. 1733.[67]

| Japanese text[64] | Romanized Japanese | English translation[68][p] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Kyōdai no shūgetsu

[edit]-

Without seal, and with altered details

-

Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version, 1769

Kyōdai no shūgetsu (鏡台の秋月, "Harvest moon of the mirror stand") parodies Harvest Moon over Dongting Lake (洞庭秋月 Dōtei shūgetsu).[37] The print depicts a hairdresser doing up the hair of a young girl in a long-sleeved kimono with a pattern of plovers flying over waves, which perhaps alludes to the surface of Dongting Lake. The flowering Japanese pampas grass indicates an autumn scene,[69] and the round mirror before them alludes to the autumnal harvest moon.[63] With the young woman's face reflecting in the mirror, Haruo Shirane sees further allusion to Ōmi Hakkei's Ishiyama Shūgetsu, which traditionally has the harvest moon at Ishiyama Temple reflect off Lake Biwa.[70]

In the Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version a husband, smoking a pipe, embraces his half-naked wife from behind, pulls at her kimono,[65] and fondles her genitals[70] as she applies makeup. Her eyebrows are unshaved, which indicates she is newly wed and has not yet had a child. An amulet for a paper charm dangles from her neck. The mirror before her alludes to the moon in The Moon in Autumn on Dongting Lake.[65] A nadeshiko fringed pink grows in a potter on the veranda, which suggests the word nadeshiko, meaning "a child who is caressed", but used to mean "the woman I love" in ancient waka poetry.[71] The nadeshiko fringed pink was also a traditional symbol of a beautiful, desirable woman.[13] To Hayakawa, the woman's body partly covered by the kimono is an allusion to the accompanying poem's "mid-autumn full moon ... hidden in the clouds".[72] The word utena puns on the homophones for pedestal[y] and the calyx[z] of a flower, a traditional metaphor for the female genitals; thus the moon climbing the utena can be read as the man mounting the woman.[70] To Shirane, the opening and closing "Moon of an autumn evening" in the poem creates a "mirror effect" appropriate to the image of the mirror.[70]

| Japanese text[65] | Romanized Japanese | English translation[70][aa] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Andon no sekishō

[edit]-

Andon no sekishō, 1766

-

Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version, 1769

-

From Furyū Iro Hakkei, Nishikawa Sukenobu, 1715

Andon no sekishō (行燈の夕照, "Evening Glow of the Lamp") parodies Fishing Village in the Evening Glow (漁村夕照 Gyoson sekishō).[37]

The print depicts an autumn scene with coloured leaves on the trees in the background.[73] A woman—likely a nobleman's wife—in a short-sleeved black kimono with its obi tied in the front, an old-fashioned style at the time.[69] She reads a letter in the rapidly sinking sun as her daughter readies the andon paper lamp. The artificial lamplight alludes to the sunset and the water outside to the fishing village of The Fishing Village in the Evening Glow.[73]

In the Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version a woman, carrying an andon lamp and identifiable as pregnant by the iwataobi sash around her belly, walks in on her husband having sex with another woman, likely a housemaid.[74] The wife's expression is of anger, the husband's of surprise, and the other woman's of ecstasy. Hayakawa identifies the mitate with setting sun of The Fishing Village in the Evening Glow as the waning passion of the husband for his wife during her pregnancy.[75] Harunobu appears to have appropriated the positioning of the copulating figures from the eighth page of Sukenobu's Furyū Iro Hakkei of 1715 for the Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei.[61]

| Japanese text[71] | Romanized Japanese | English translation[76][p] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Daisu no yau

[edit]-

Daisu no yau, 1766

-

A state of Daisu no yau with an embossed background

-

Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version, 1769

Daisu no yau (台子の夜雨, "Night rain on the daisu") parodies Rain at Night on the Xiaoxiang (瀟湘夜雨 Shōshō yau).[37]

Harunobu sets the print in the tea room of a machiya merchant's home.[77] A teapot and other items are set out on a daisu tea utensil stand, before which dozes a young girl as she sits. A young boy appears about to play some mischief with her hair while another girl in a long-sleeved kimono smiles at it behind him.[78] Hayakawa and others sees the mitate as the sound of boiling water in the pot representing the rain in Rain at Night on the Xiaoxiang.[29][78]

In the Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version a man has forcible sex with a woman holding a piece of kaishi paper used in the tea ceremony. From between the shōji peeps a woman with a hand to her mouth in surprise. She has shaved eyebrows, signifying she has already given birth and thus is likely the man's wife. The boiling teapot again to Hayakawa represents the "sound of rain on the wooden floor" in the accompanying poem; he further speculates the sound of rain represents the unease the woman feels at her husband's waning passion for her.[79]

| Japanese text[79] | Romanized Japanese | English translation[80][p] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Tenuguikake no kihan

[edit]-

Tenuguikake no kihan, 1766

-

Erotic Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version, 1769

-

From Nanshoku Yamaji no Tsuyu, Nishikawa Sukenobu, 1715

Tenuguikake no kihan (手拭いかけの帰帆, "Returning sails of the towel rack") parodies Ship Returning from a Distant Bay (遠浦帰帆 Enpo kihan).[37] Towels blowing in the breeze from a towel rack on the veranda of a tea room in the print allude to the returning sailing ships. Beside it the mistress of the house is using a bucket meant for washing the hands and face; her kimono is patterned with riverside threeleaf arrowheads, a plant associated with summer. A housemaid sits inside sewing; an uchiwa hand fan lies on the floor beside her.[81]

A Japanese rock garden lies outside in the background of the Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei version, in which a middle-aged man has his beard plucked by a young woman. The man has one arm around the woman and reaches for her kimono as they kiss.[82] Hayakawa assumes the young woman is the man's mistress, and interprets her as the "distant bay" to whom the older man "returns", or as the male ship pulling into the female harbour.[83]

Harunobu appears to have appropriated background and the positioning of the copulating figures from the final volume of Sukenobu's Nanshoku Yamaji no Tsuyu of c. 1733 for the Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei. This includes details such as the reflection of the couple's faces in a round mirror and a garden in the background with stepping stones and a bamboo gate.[84]

| Japanese text[82] | Romanized Japanese | English translation[85][p] |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Zashiki Hakkei by other artists

[edit]Torii Kiyonaga produced two series based on Harunobu's Zashiki Hakkei.[86] The first was Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei in c. 1777, and of the two series more closely follows the arrangement of figures in Harunobu's Zashiki Hakkei (not Harunobu's Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei), but with the hairstyles and clothing altered to current fashions.[87] The prints include the poems from Harunobu's Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei, with minor differences in orthography.[36] Kiyonobu produced another, different Zashiki Hakkei in c. 1778.[86]

The Zashiki Hakkei theme appears to have become popular, and other artists designed their own versions, sometimes incorporating the poems from Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei.[36] Isoda Koryūsai produced two series in the early 1770s titled Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei—one chūban-sized, the other hashira-e pillar prints—but he does not appear to have based them directly on Harunobu's. Other artists who produced prints on the theme include Utamaro.[86]

- Other artist's versions of Zashiki Hakkei

-

Sensu no seiran, Kiyonaga, c. 1778

Notes

[edit]- ^ The 1766 series uses the character 坐 za, while other versions mentioned use the character 座 za.[1] Sources often use the latter character regardless.

- ^ 大紹会 daishōkai, "large and small association"; the cultured participants at these parties competed in producing pictures that displayed which months each year were "large" (大 dai, with 30 days) and "small" (小 shō, those with 29 days).[6]

- ^ 大紹会 近江八景の内, Ōmi Hakkei no Uchi, "From the Eight Views of Ōmi"

- ^ 19 by 22.5 centimetres, 7.5 in × 8.9 in

- ^ 松鶴堂 Shokakudō

- ^ Meiwa 3 on the Japanese calendar[15]

- ^ The packet displays the title as 風流繪合 坐鋪八景 城西山人巨川工 Fūryū E-awase Zashiki Hakkei Jōsai Sanjin Kyosen, "Fashionable picture collection Zashiki Hakkei, devised by Jōsai Sanjin Kyosen".[18]

- ^ Meiwa 5–6[23] or 7[24] on the Japanese calendar

- ^ 福尾 吉次郎 Fukuo Kichijirō

- ^ 永田 貞柳 Nagata Teiryū, also known as Taiya Teiryū 鯛屋 貞柳[27]

- ^ 享保世説 Kyōhō Sesetsu, "Kyōhō Rumours"

- ^ Kinkyokushū 琴曲集, "Collection of koto music"

- ^ Kinkyokushū 琴曲抄, "Selection of koto music"

- ^ Fuki 菜蕗, the Japanese name of the Petasites japonicus plant

- ^ Translation by Leonard Holvik, 1992

- ^ a b c d e f g Translation by Patricia J. Fister, 2001

- ^ The first three lines of Kichijirō's version read:

琴糸や 引とめられし 雁金の

kotoito ya hikitomerareshi karigane no[48] - ^ Ōgi (扇), also called sensu (扇子)

- ^ とみよしや前 Tomiyoshi-ya mae

- ^ 松もとや前 Matsumotoya mae

- ^ 川端を歩く芸者と少女 Kawabata wo aruku geisha to shōjo, signed "Harunobu" but authenticity questioned

- ^ 濡姿逢初川 Nure-sugata Aizomekawa

- ^ 風流色八景 Furyū Iro Hakkei

- ^ 男色山路露 Nanshoku Yamaji no Tsuyu, in three volumes[66]

- ^ 台 utena, "pedestal"

- ^ 萼 utena, "calyx"

- ^ Translation by Haruo Shirane

- ^ 唐崎夜雨 Karasaki yau, "Night rain at Karasaki"

- ^ 当世座敷八景 Tōsei Zashiki Hakkei, "Contemporary eight parlour views"

References

[edit]- ^ Ishigami 2015, p. 202.

- ^ a b Davis 2015, p. 13.

- ^ Kikuchi & Kenny 1969, p. 31.

- ^ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 76–77.

- ^ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 80–82.

- ^ a b Nishiyama 1997, p. 70.

- ^ a b c d Hayakawa 2002, p. 58.

- ^ Kobayashi 1997, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Lane 1962, pp. 150, 152.

- ^ Ortiz 1999, p. 28.

- ^ Hayakawa 2002, p. 59.

- ^ Shirane 2010, pp. 51–52.

- ^ a b Hayakawa 2013, p. 110.

- ^ Shirane 2010, pp. 53–54.

- ^ a b c d e f Ishigami 2008, p. 69.

- ^ a b c d Gookin 1922, p. 10.

- ^ Takahashi 1968, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e f Kobayashi 1991, p. 9.

- ^ Hempel & Holler 1995, p. 14.

- ^ Hayashi 2011, p. 83.

- ^ a b Ishigami 2015, p. 215.

- ^ Ishigami 2015, p. 218.

- ^ a b Ishigami 2015, p. 201.

- ^ a b Hayashi 2011, p. 135.

- ^ a b c Hayashi 2011, p. 133.

- ^ Ishigami 2008, pp. 69, 86.

- ^ Ishigami 2015, p. 2.

- ^ a b Hayakawa 2002, pp. 62–63.

- ^ a b Shirane 2010, p. 54.

- ^ a b Ishigami 2008, p. 83.

- ^ Ishigami 2008, p. 85.

- ^ Ishigami 2008, pp. 85–86.

- ^ a b Ishigami 2008, p. 86.

- ^ Fukuda 2015, p. 34.

- ^ Hayakawa 2010, p. 38.

- ^ a b c d Ishigami 2015, p. 225.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Zhu 2010, p. 133.

- ^ Hayakawa 2002, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Coaldrake 2012, p. 113.

- ^ a b Hayakawa 2002, p. 64.

- ^ Fletcher & Rossing 2013, p. 334.

- ^ a b Coaldrake 2012, p. 120.

- ^ Holvik 1992, pp. 465–466.

- ^ Coaldrake 2012, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Holvik 1992, p. 463.

- ^ Coaldrake 2012, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d Hayakawa 2002, p. 73.

- ^ a b c d Ishigami 2015, p. 204.

- ^ a b Hayakawa 2002, p. 74.

- ^ a b c Hayakawa 2002, p. 75.

- ^ Hayakawa 2001, p. 89.

- ^ Ishigami 2015, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Hayakawa 2002, p. 65.

- ^ Kobayashi 1991, p. 130.

- ^ Ishigami 2008, p. 84.

- ^ Hayakawa 2001, p. 91.

- ^ Hayakawa 2002, p. 66.

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art staff.

- ^ a b Hayakawa 2002, p. 78.

- ^ Hayakawa 2002, p. 79.

- ^ a b Ishigami 2015, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Hayakawa 2001, p. 101.

- ^ a b Hayakawa 2002, p. 67.

- ^ a b Hayakawa 2002, p. 80.

- ^ a b c d Hayakawa 2002, p. 81.

- ^ Ishigami 2015, p. 216.

- ^ Ishigami 2015, pp. 219–221.

- ^ Hayakawa 2001, p. 94.

- ^ a b Hayakawa 2002, p. 68.

- ^ a b c d e Shirane 2010, p. 63.

- ^ a b Hayakawa 2002, p. 83.

- ^ Hayakawa 2002, p. 82.

- ^ a b Hayakawa 2002, p. 69.

- ^ Hayakawa 2002, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Hayakawa 2002, p. 84.

- ^ Hayakawa 2001, p. 97.

- ^ Hayakawa 2002, pp. 69–70.

- ^ a b Hayakawa 2002, p. 70.

- ^ a b Hayakawa 2002, p. 85.

- ^ Hayakawa 2001, p. 98.

- ^ Hayakawa 2002, p. 71.

- ^ a b Hayakawa 2002, p. 87.

- ^ Hayakawa 2002, p. 88.

- ^ Ishigami 2015, pp. 216, 218.

- ^ Hayakawa 2001, p. 100.

- ^ a b c Ishigami 2015, p. 224.

- ^ Ishigami 2015, pp. 224–225.

Works cited

[edit]- Coaldrake, Kimi (May 2012). "Nishiki-e and Kumi-uta: Innovations in Edo Popular Prints and Music in Suzuki Harunobu's Descending Geese of the Koto Bridges (Kotoji no rakugan)". Japanese Studies. 32 (1): 113–127. doi:10.1080/10371397.2012.669728. ISSN 1469-9338. S2CID 144371789.

- Davis, Julie Nelson (2015). Partners in Print: Artistic Collaboration and the Ukiyo-e Market. University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-5440-9 – via Project MUSE.

- Fletcher, Neville H.; Rossing, Thomas (2013). The Physics of Musical Instruments. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-21603-4.

- Fukuda, Hiromi (January 2015). "Torii Kiyonaga no ukiyo-e ni miru fukushoku byōsha no dokujisei: Shitaimi to senshoku hyōmen" 鳥居清長の浮世絵に見る服飾描写の独自性—姿態美と染織表現— [Torii Kiyonaga's Characteristic Fashion Portrayal of the Costumes in Ukiyo-e: Figure Beauty and Textile Dyeing Expression]. Journal of Bunka Gakuen University: Studies on Fashion Science & Art Design (in Japanese). 46: 33–45. hdl:10457/2268. ISSN 1346-1869.

- Gookin, Frederick W. (1922). Illustrated Catalogue of Japanese Color Prints, The Famous Collection of the Late Alexis Rouart of Paris, France together with a Selection from the Collection of the Vicomte de Sartiges and a Few Prints from Another Parisian Collection (PDF). American Art Association – via Internet Archive.

- Holvik, Leonard C. (Summer 1992). "Echoes and Shadows: Integration and Purpose in the Words of the Koto Composition 'Fuki'". The Journal of Japanese Studies. 18 (2): 445–477. doi:10.2307/132827. JSTOR 132827.

- Hayakawa, Monta (2001). "Explanations of the Illustrations in the Fūryū zashiki hakkei" (PDF). The Shunga of Suzuki Harunobu: Mitate-e and Sexuality in Edo. Nichibunken Monograph Series. Vol. 4. Translated by Fister, Patricia J. International Research Center for Japanese Studies. pp. 89–104. Retrieved 2016-03-25.

- Hayakawa, Monta (2002). Harunobu no haru, Edo no haru 春信の春、江戸の春 [Harunobu's spring, Edo's spring] (in Japanese). Bungeishunjū. ISBN 978-4-16-660274-2.

- Hayakawa, Monta; Jōchi Daigaku Kokubun Jogakusei no Kai (2010). Gendaigoyaku shunga: kotobagaki to kakiire o yomu 現代語訳春画: 詞書と書入れを読む. Shin Jinbutsu Ōraisha. ISBN 978-4-404-03833-3.

- Hayakawa, Monta (2013). Shunga: Ten Questions and Answers. Nichibunken Monograph Series. Vol. 14. Translated by Gerstle, C. Andrew. International Research Center for Japanese Studies . ISBN 978-4-901558-63-1.

- Hayashi, Yoshikazu (2011). Nakano, Mitsutoshi; Kobayashi, Tadashi (eds.). Suzuki Harunobu, Isoda Koryūsai 鈴木春信・磯田湖龍齋. 江戶艶本集成. Vol. 2. Kawade Shobō Shinsha. ISBN 978-4-309-71626-8.

- Hempel, Rose; Holler, Wolfgang (1995). Gems of the Floating World: Ukiyo-e Prints from the Dresden Kupferstich-Kabinett. Japan Society. ISBN 978-0-913304-39-6.

- Ishigami, Aki (2008). "Suzuki Harunobu-ga Fūryū zashiki hakkei kō: Gachū kyōka no riyū to zugara no tenky0" 鈴木春信画『風流座敷八景』考―画中狂歌の利用と図柄の典拠― [A Study of Fūryū Zashiki Hakkei by Suzuki Harunobu: The Use of Kyōka Poems in Pictorial Composition and Design Sources]. Ukiyo-e Geijutsu (in Japanese) (156): 69–87. ISSN 0041-5979.

- Ishigami, Aki (2015). Nihon no shunga, ehon kenkyū 日本の春画・艶本研究 [Japanese shunga, ehon research] (in Japanese). Heibonsha. ISBN 978-4-582-66216-0.

- Kikuchi, Sadao; Kenny, Don (1969). A Treasury of Japanese Wood Block Prints (Ukiyo-e). Crown Publishers. OCLC 21250.

- Kobayashi, Tadashi, ed. (1991). Harunobu, Harushige, Kōryūsai, hoka shoki ukiyo-e 春信 春重・湖竜斎ほか初期浮世絵 [Harunobu, Harushige, Kōryūsai and other early ukiyo-e]. Meihin soroimono ukiyo-e (in Japanese). Vol. 1. Gyōsei. ISBN 978-4-324-02486-7.

- Kobayashi, Tadashi (1997). Ukiyo-e: An Introduction to Japanese Woodblock Prints. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-4-7700-2182-3.

- Lane, Richard (1962). Masters of the Japanese Print: Their World and Their Work. Doubleday. OCLC 185540172.[ISBN missing]

- Metropolitan Museum of Art staff. "Evening Snow on the Heater". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2016-03-09.

- Nishiyama, Matsunosuke (1997). Edo Culture: Daily Life and Diversions in Urban Japan, 1600–1868. Translated by Groemer, Gerald. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1850-0.

- Ortiz, Valérie Malenfer (1999). Dreaming the Southern Song Landscape: The Power of Illusion in Chinese Painting. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-11011-3.

- Shirane, Haruo (2010). "Dressing Up, Dressing Down: Poetry, Image and Transposition in the Eight Views". Impressions (31): 50–71. JSTOR 42597696.

- Takahashi, Seiichirō (1968). Harunobu. Kodansha International. ISBN 978-0-87011-070-2.

- Zhu, Meizhen (2010-10-31). "Ukiyo-e ni okeru "mitate" sōsa no tokuchō – Shōwaki no sakuhin wo chūshin ni" 浮世絵における「見立て」操作の特徴 -昭和期の作品を中心に-. 法政大学大学院紀要 (in Japanese): 125–139. hdl:10114/6147. ISSN 0387-2610.

External links

[edit] Media related to Zashiki hakkei at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Zashiki hakkei at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Fūryū zashiki hakkei at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Fūryū zashiki hakkei at Wikimedia Commons

![Shōkei's [ja] version of Evening Gong at Qingliang Temple, early 16th century](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/77/Kenk%C5%8D_Sh%C5%8Dkei_-_Sh%C5%8Dsh%C5%8D_Hakkei_-_Enji_Bansh%C5%8D.png/176px-Kenk%C5%8D_Sh%C5%8Dkei_-_Sh%C5%8Dsh%C5%8D_Hakkei_-_Enji_Bansh%C5%8D.png)

![Karasaki yau,[ab] from Tōsei Zashiki Hakkei,[ac] Utamaro, c. late 18th century](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/db/Utamaro_-_T%C5%8Dsei_Zashiki_Hakkei_-_Karasaki_yau.jpg/203px-Utamaro_-_T%C5%8Dsei_Zashiki_Hakkei_-_Karasaki_yau.jpg)