Nuclear arms race: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 116.39.110.175 (talk) addition of unsourced content (HG) |

Iloverussia (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

| style="text-align:center;"| 1978 |

| style="text-align:center;"| 1978 |

||

| 2,058 |

| 2,058 |

||

| 2, |

| 2,420 |

||

| 9,800 |

| 9,800 |

||

| 5,200 |

| 5,200 |

||

Revision as of 07:19, 24 January 2012

| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

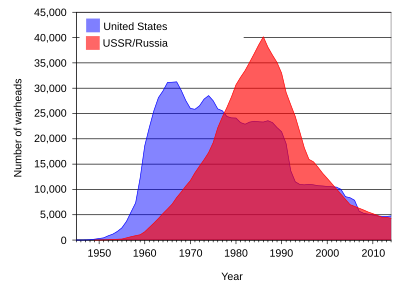

The nuclear arms race was a competition for supremacy in nuclear warfare between the United States, the Soviet Union, and their respective allies during the Cold War. During the Cold War, in addition to the American and Soviet nuclear stockpiles, other countries developed nuclear weapons, though none engaged in warhead production on nearly the same scale as the two superpowers.

World War II

The first nuclear weapon was created by the Manhattan Project during the Second World War and was developed to be used against the Axis powers.[1] Scientists of the Soviet Union were aware of the potential of nuclear weapons and had also been conducting research in the field.[2]

The Soviet Union was not informed officially of the Manhattan Project until Stalin was briefed at the Potsdam Conference on July 24, 1945, by U.S. President Harry S. Truman,[3][4] eight days after the first successful test of a nuclear weapon. Despite their wartime military alliance, the United States and Britain had not trusted the Soviets enough to keep knowledge of the Manhattan Project safe from German spies: there were also concerns that, as an ally, the Soviet Union would request and expect to receive technical details of the new weapon.

When President Truman informed Stalin of the weapons, he was surprised at how calmly Stalin reacted to the news and thought that Stalin had not understood what he had been told. Other members of the United States and British delegations who closely observed the exchange formed the same conclusion.

In fact Stalin had long been aware of the program.[5], despite the Manhattan Project having a secret classification so high that, even as Vice-President, Truman did not know about it or the development of the weapons. Truman was not informed until shortly after he became president.[5] A ring of spies operating within the Manhattan Project, (including Klaus Fuchs [6] and Theodore Hall) had kept Stalin well informed of American progress.[7]

In August 1945, on Truman's orders, two atomic bombs were dropped on Japanese cities. The first bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, and the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki by the B-29 bombers named Enola Gay and Bockscar respectively.

Early Cold War

In the years immediately after the Second World War, the United States had a monopoly on specific knowledge of and raw materials for nuclear weaponry. Initially, it was thought that uranium was rare in the world but this turned out to be wrong. American leaders hoped that their exclusive ownership of nuclear weapons would be enough to draw concessions from the Soviet Union but this proved ineffective.

Behind the scenes, the Soviet regime was working on building its own atomic weapons. During the war, Soviet efforts had been limited by a lack of uranium but new supplies in Eastern Europe were found and provided a steady supply while the Soviets developed a domestic source. While American experts had predicted that the USSR would not have nuclear weapons until the mid-1950s, the first Soviet bomb was detonated on August 29, 1949, shocking the entire world. The bomb, named "Joe One" by the West, was more or less a copy of "Fat Man", one of the bombs the United States had dropped on Japan in 1945.

Both governments spent massive amounts to increase the quality and quantity of their nuclear arsenals. Both nations quickly began the development of a hydrogen bomb and the United States detonated the first of these on November 1, 1952. Again, the Soviets surprised the world by exploding a deployable thermonuclear device in August 1953 although it was not a true multi-stage hydrogen bomb: this weapon followed in 1955.

The most important development in terms of delivery in the 1950s was the introduction of intercontinental ballistic missiles, ICBMs. Missiles had long been regarded the ideal platform for nuclear weapons, and were potentially a more effective delivery system than strategic bombers, which was the primary delivery method at the beginning of the Cold War. On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union showed the world that they had missiles able to reach any part of the world when they launched the Sputnik satellite into Earth orbit. The United States launched their own satellite on the 31 October 1959. The Space Race showcased technology critical to the delivery of nuclear weapons, the ICBM boosters, while maintaining the appearance of being for science and exploration.

This period also saw some of the first attempts to defend against nuclear weapons. Both superpowers built large radar arrays to detect incoming bombers and missiles. Fighters to use against bombers and anti-ballistic missiles to use against ICBMs were also developed. Large underground bunkers were constructed to save the leaders, and citizens were told to build fallout shelters and taught how to react to a nuclear attack. These measurements were called civil defense.

Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD)

None of these defensive measures were secure, and in the 1950s both the United States and Soviet Union had nuclear power to obliterate the other side. Both sides developed a capability to launch a devastating attack even after sustaining a full assault from the other side (especially by means of submarines), called a second strike.[8] This policy was part of what became known as Mutual Assured Destruction: both sides knew that any attack upon the other would be devastating to themselves, thus in theory refraining them from attacking the other.

Both Soviet and American experts hoped to use nuclear weapons for extracting concessions from the other, or from other powers such as China, but the risk connected with using these weapons was so grave that they refrained from what John Foster Dulles referred to as brinkmanship. While some, like General Douglas MacArthur, argued nuclear weapons should be used during the Korean War, both Truman and Eisenhower opposed.

Both sides were unaware of the capacity of the enemy's arsenal of nuclear weapons. The Americans suffered from a lack of confidence, and in the 1950s they believed in a non-existing bomber gap. Aerial photography later revealed that the Soviets had been playing a sort of Potemkin village game with their bombers in their military parades, flying them in large circles, making it appear they had far more than they truly did. The 1960 American presidential election saw accusations of a wholly spurious missile gap between the Soviets and the Americans. On the contrary, the Soviet government exaggerated the power of Soviet weapons to the leadership and Nikita Khrushchev.

An additional controversy formed in the United States during the early 1960s concerned whether or not it was certain if their weapons would work if the need should occur. All of the individual components of nuclear missiles had been tested separately (warheads, navigation systems, rockets), but it had been infeasible to test them all combined. Critics charged that it was not really known how a warhead would react to the gravity forces and temperature differences encountered in the upper atmosphere and outer space, and Kennedy was unwilling to run a test of an ICBM with a live warhead. The closest thing to an actual test was 1962's Operation Frigate Bird, in which the submarine USS Ethan Allen launched a Polaris A1 missile over 1,000 miles to the nuclear test site at Christmas Island. It was challenged by, among others, Curtis LeMay, who put missile accuracy into doubt to encourage the development of new bombers. Other critics pointed out that it was a single test which could be an anomaly; that it was a lower-altitude SLBM and therefore was subject to different conditions than an ICBM; and that significant modifications had been made to its warhead before testing.

| Year | Launchers | Warheads | Megatonnage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | USSR | USA | USSR | USA | USSR | |

| 1964 | 2,416 | 375 | 6,800 | 500 | 7,500 | 1,000 |

| 1966 | 2,396 | 435 | 5,000 | 550 | 5,600 | 1,200 |

| 1968 | 2,360 | 1,045 | 4,500 | 850 | 5,100 | 2,300 |

| 1970 | 2,230 | 1,680 | 3,900 | 1,800 | 4,300 | 3,100 |

| 1972 | 2,230 | 2,090 | 5,800 | 2,100 | 4,100 | 4,000 |

| 1974 | 2,180 | 2,380 | 8,400 | 2,400 | 3,800 | 4,200 |

| 1976 | 2,100 | 2,390 | 9,400 | 3,200 | 3,700 | 4,500 |

| 1978 | 2,058 | 2,420 | 9,800 | 5,200 | 3,800 | 5,400 |

| 1980 | 2,042 | 2,490 | 10,000 | 7,200 | 4,000 | 6,200 |

| 1982 | 2,032 | 2,490 | 11,000 | 10,000 | 4,100 | 8,200 |

Initial nuclear proliferation

In addition to the United States and the Soviet Union, three other nations, the United Kingdom,[11] People's Republic of China,[12] and France[13] also developed far smaller nuclear stockpiles. In 1952, the United Kingdom became the third nation to possess nuclear weapons when it detonated an atomic bomb in Operation Hurricane[14] in Australia on October 3, 1952. During the Cold War, British nuclear deterrence came from submarines and nuclear-armed aircraft. The Resolution class ballistic missile submarines armed with the American-built Polaris missile provided the sea deterrent, while aircraft such as the Avro Vulcan, SEPECAT Jaguar, Panavia Tornado and several other Royal Air Force strike aircraft carrying WE.177 gravity bomb provided the air deterrent.

France became the fourth nation to possess nuclear weapons on February 13, 1960, when the atomic bomb Gerboise Bleue was detonated in Algeria,[15] then still a French colony [Formally a part of the Metropolitan France.] During the Cold War, the French nuclear deterent was centered around the Force de frappe, a nuclear triad consisting of Dassault Mirage IV bombers carrying such nuclear weapons as the AN-22 gravity bomb and the ASMP stand-off attack missile, Pluton and Hades ballistic missiles, and the Redoutable class submarine armed with strategic nuclear missiles.

The People's Republic of China became the fifth nuclear power on October 16, 1964 when it detonated a uranium-235 bomb in a test codenamed 596.[16] Due to Soviet/Chinese tensions, the Chinese might have used nuclear weapons against either the United States or the Soviet Union in the event of a nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union[citation needed]. During the Cold War, the Chinese nuclear deterrent consisted of gravity bombs carried aboard H-6 bomber aircraft, missile systems such as the DF-2, DF-3, and DF-4,[17] and in the later stages of the Cold War, the Type 092 ballistic missile submarine.

Richard Nixon's Program of Détente

Economic problems caused by the arms race in both powers, combined with China's new role and the ability to verify disarmament led to a number of arms control agreements beginning in the 1970s. This period known as détente allowed both states to reduce their spending on weapons systems. SALT I and SALT II limited the size of the states arsenals. Bans on nuclear testing, anti-ballistic missile systems, and weapons in space all attempted to limit the expansion of the arms race through the Partial Test Ban Treaty.

These treaties were only partially successful. Both states continued building massive numbers of nuclear weapons, and new technologies such as multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (also known as MIRVs) limited the effectiveness of the treaties. Both superpowers retained the ability to destroy each other many times over.

Reagan and the Strategic Defense Initiative

Towards the end of Jimmy Carter's presidency, and continued strongly through the subsequent presidency of Ronald Reagan, the United States rejected disarmament and tried to restart the arms race through the production of new weapons and anti-weapons systems. The central part of this strategy was the Strategic Defense Initiative, a space based anti-ballistic missile system derided as "Star Wars" by its critics. During the second part of 1980s, the Soviet economy was teetering towards collapse and was unable to match American arms spending. Numerous negotiations by Mikhail Gorbachev attempted to come to agreements on reducing nuclear stockpiles, but the most radical were rejected by Reagan as they would also prohibit his SDI program.

Post–Cold War

With the end of the Cold War the United States, and especially Russia, cut down on nuclear weapons spending. Fewer new systems were developed and both arsenals have shrunk. But both countries still maintain stocks of nuclear missiles numbering in the thousands. In the USA, stockpile stewardship programs have taken over the role of maintaining the aging arsenal.

After the Cold War ended, a large amount of resources and money which was once spent on developing nuclear weapons in USSR was then spent on repairing the environmental damage produced by the nuclear arms race, and almost all former production sites are now major cleanup sites. In the USA, the plutonium production facility at Hanford, Washington and the plutonium pit fabrication facility at Rocky Flats, Colorado are among the most polluted sites.

United States policy and strategy regarding nuclear proliferation was outlined in 1995 in the document "Essentials of Post–Cold War Deterrence".

Despite efforts made in cleaning up uranium sites, significant problems stemming from the legacy of uranium development still exist today on the Navajo Nation in the states of Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona. Hundreds of abandoned mines have not been cleaned up and present environmental and health risks in many Navajo communities.

India and Pakistan

The South-Asian states of India and Pakistan have also engaged in a nuclear arms race. India detonated what it called a "peaceful nuclear device" in 1974 ("Smiling Buddha") [18] much to the surprise and alarm of the world who had been giving India nuclear technology for civilian, energy producing and peaceful purposes. The test generated great concern in Pakistan, which feared that it would be at the mercy of its long-time arch rival and quickly responded by pursuing its own nuclear weapons program. In the last few decades of the 20th century, Pakistan and India began to develop nuclear-capable rockets, and Pakistan had its own covert bomb program which extended over many years since the first Indian weapon was detonated. In 1998 India, under Atal Bihari Vajpayee government, test detonated 5 more nuclear weapons. While the international response to the detonation was muted[citation needed], domestic pressure within Pakistan began to build steam and Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif ordered the test, detonated 6 nuclear war weapons in a tit-for-tat fashion and to act as a deterrent.

See also

- Nuclear warfare

- Essentials of Post–Cold War Deterrence

- Deterrence theory

- Nuclear disarmament

- Nuclear-free zone

- Space race

- TNT equivalent

- Brinkmanship

- Brinkmanship (Cold War)

References

- ^ Key Issues: Nuclear Weapons: History: Pre Cold War: Manhattan Project

- ^ The Soviet Nuclear Weapons Program

- ^ The Potsdam Conference between allied forces

- ^ Atomic Bomb: Decision - Truman Tells Stalin, July 24, 1945

- ^ a b Potsdam Note (Animation)

- ^ Klaus Fuchs: Atom Bomb Spy

- ^ Los Alamos National Laboratory: History: People of Wartime Los Alamos: Spies

- ^ scramble

- ^ Gerards Segal, The Simon & Schuster Guide to the World Today, (Simon & Schuster, 1987), p. 82

- ^ Edwin Bacon, Mark Sandle, "Brezhnev Reconsidered", Studies in Russian and East European History and Society (Palgrave Macmillan, 2003)

- ^ United Kingdom Nuclear Forces

- ^ China Nuclear Forces

- ^ France Nuclear Forces

- ^ A toxic legacy : British nuclear weapons testing in Australia [in: Wayward governance : illegality and its control in the public sector]

- ^ Chapitre II, Les premiers essais Français au Sahara : 1960-1966 Senat.fr (in French)

- ^ China's Nuclear Weapons

- ^ Theater Missile Systems - China Nuclear Forces

- ^ India's Nuclear Weapons Program - Smiling Buddha: 1974

External links

- Erik Ringmar, "The Recognition Game: Soviet Russia Against the West," Cooperation & Conflict, 37:2, 2002. pp. 115–36. -- the arms race between the superpowers explained through the concept of recognition.

- Annotated bibliography on the nuclear arms race from the Alsos Digital Library for Nuclear Issues