List of states with nuclear weapons

| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

Eight sovereign states have publicly announced successful detonation of nuclear weapons.[1] Five are considered to be nuclear-weapon states (NWS) under the terms of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT). In order of acquisition of nuclear weapons, these are the United States, Russia (the successor of the former Soviet Union), the United Kingdom, France, and China. Of these, the three NATO members, the United Kingdom, the United States, and France, are sometimes termed the P3.[2]

Other states that possess nuclear weapons are India, Pakistan, and North Korea. Since the NPT entered into force in 1970, these three states were not parties to the Treaty and have conducted overt nuclear tests. North Korea had been a party to the NPT but withdrew in 2003.

Israel is also generally understood to have nuclear weapons, but does not acknowledge it, maintaining a policy of deliberate ambiguity.[3] Israel is estimated to possess somewhere between 75 and 400 nuclear warheads.[4][5] One possible motivation for nuclear ambiguity is deterrence with minimum political friction.[6][7]

States that formerly possessed nuclear weapons are South Africa (developed nuclear weapons but then disassembled its arsenal before joining the NPT)[8] and the former Soviet republics of Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine, whose weapons were transferred to Russia.

According to the Federation of American Scientists there are approximately 3,880 active nuclear warheads and 12,119 total nuclear warheads in the world as of 2024.[9] The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) estimated in 2023 that the total number of nuclear warheads acquired by nuclear states reached 12,512. Approximately 9,576 are kept with military stockpiles. About 3,844 warheads are deployed with missiles. 2,000 warheads, which are primarily from Russia and the United States, are maintained for high operational alerts.[10]

Statistics and force configuration

The following is a list of states that have acknowledged the possession of nuclear weapons or are presumed to possess them, the approximate number of warheads under their control, and the year they tested their first weapon and their force configuration. This list is informally known in global politics as the "Nuclear Club".[11][12] With the exception of Russia and the United States (which have subjected their nuclear forces to independent verification under various treaties) these figures are estimates, in some cases quite unreliable estimates. In particular, under the Strategic Offensive Reductions Treaty thousands of Russian and US nuclear warheads are inactive in stockpiles awaiting processing. The fissile material contained in the warheads can then be recycled for use in nuclear reactors.

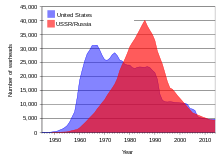

From a high of 70,300 active weapons in 1986, as of 2024[update] there are approximately 3,880 active nuclear warheads and 12,119 total nuclear warheads in the world.[9] Many of the decommissioned weapons were simply stored or partially dismantled, not destroyed.[13]

Additionally, since the dawn of the Atomic Age, the delivery methods of most states with nuclear weapons have evolved—with four acquiring a nuclear triad, while others have consolidated away from land and air deterrents to submarine-based forces.

Percentage of global nuclear warheads by country

Recognized nuclear-weapon states

These five states are known to have detonated a nuclear explosive before 1 January 1967 and are thus nuclear weapons states under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons. They also happen to be the UN Security Council's (UNSC) permanent members with veto power on UNSC resolutions.

United States

The United States developed the first nuclear weapons during World War II in cooperation with the United Kingdom and Canada as part of the Manhattan Project, out of the apprehension that Nazi Germany would develop them first. It tested the first nuclear weapon on 16 July 1945 ("Trinity") at 5:30 am, and remains the only country to have used nuclear weapons in war, having bombed the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the closing stages of World War II. The project expenditure through 1 October 1945 was reportedly $1.845–$2 billion, in nominal terms,[46][47] roughly 0.8 percent of the US GDP in 1945 and equivalent to about $32.5 billion today.[48]

The United States was the first nation to develop the hydrogen bomb, testing an experimental prototype in 1952 ("Ivy Mike") and a deployable weapon in 1954 ("Castle Bravo"). Throughout the Cold War it continued to modernize and enlarge its nuclear arsenal, but from 1992 on has been involved primarily in a program of stockpile stewardship.[49][50][51][52] The US nuclear arsenal contained 31,175 warheads at its Cold War height (in 1966).[53] During the Cold War, the United States built more nuclear weapons than all other nations at approximately 70,000 warheads.[54][55]

Russia (successor to the Soviet Union)

The Soviet Union tested its first nuclear weapon ("RDS-1") in 1949. This crash project was developed partially with information obtained via the atomic spies at the United States' Manhattan Project during and after World War II. The Soviet Union was the second nation to have developed and tested a nuclear weapon. It tested its first megaton-range hydrogen bomb ("RDS-37") in 1955. The Soviet Union also tested the most powerful explosive ever detonated by humans, ("Tsar Bomba"), with a theoretical yield of 100 megatons, reduced to 50 when detonated. After its dissolution in 1991, the Soviet weapons entered officially into the possession of its successor state, the Russian Federation.[56] The Soviet nuclear arsenal contained some 45,000 warheads at its peak (in 1986), more than any other nation had possessed at any point in history; the Soviet Union built about 55,000 nuclear warheads since 1949.[55]

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom tested its first nuclear weapon ("Hurricane") in 1952. The UK had provided considerable impetus and initial research for the early conception of the atomic bomb, aided by Austrian, German and Polish physicists working at British universities who had either fled or decided not to return to Nazi Germany or Nazi-controlled territories. The UK collaborated closely with the United States and Canada during the Manhattan Project, but had to develop its own method for manufacturing and detonating a bomb as US secrecy grew after 1945. The United Kingdom was the third country in the world, after the United States and the Soviet Union, to develop and test a nuclear weapon. Its programme was motivated to have an independent deterrent against the Soviet Union, while also maintaining its status as a great power. It tested its first hydrogen bomb in 1957 (Operation Grapple), making it the third country to do so after the United States and Soviet Union.[57][58]

The British Armed Forces maintained a fleet of V bomber strategic bombers and ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs) equipped with nuclear weapons during the Cold War. The Royal Navy currently maintains a fleet of four Vanguard-class ballistic missile submarines equipped with Trident II missiles. In 2016, the UK House of Commons voted to renew the British nuclear weapons system with the Dreadnought-class submarine, without setting a date for the commencement of service of a replacement to the current system.

France

France tested its first nuclear weapon in 1960 ("Gerboise Bleue"), based mostly on its own research. It was motivated by the Suez Crisis diplomatic tension in relation to both the Soviet Union and its allies, the United States and United Kingdom. It was also relevant to retain great power status, alongside the United Kingdom, during the post-colonial Cold War (see: Force de frappe). France tested its first hydrogen bomb in 1968 ("Opération Canopus"). After the Cold War, France has disarmed 175 warheads with the reduction and modernization of its arsenal that has now evolved to a dual system based on submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) and medium-range air-to-surface missiles (Rafale fighter-bombers). However, new nuclear weapons are in development and reformed nuclear squadrons were trained during Enduring Freedom operations in Afghanistan.[citation needed]

France acceded to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1992.[59] In January 2006, President Jacques Chirac stated a terrorist act or the use of weapons of mass destruction against France would result in a nuclear counterattack.[60] In February 2015, President François Hollande stressed the need for a nuclear deterrent in "a dangerous world". He also detailed the French deterrent as "fewer than 300" nuclear warheads, three sets of 16 submarine-launched ballistic missiles and 54 medium-range air-to-surface missiles and urged other states to show similar transparency.[61]

China

China tested its first nuclear weapon device ("596") in 1964 at the Lop Nur test site. The weapon was developed as a deterrent against both the United States and the Soviet Union. Two years later, China had a fission bomb capable of being put onto a nuclear missile. It tested its first hydrogen bomb ("Test No. 6") in 1967, 32 months after testing its first nuclear weapon (the shortest fission-to-fusion development known in history).[62] China is the only NPT nuclear-weapon state to give an unqualified negative security assurance with its "no first use" policy.[63][64] China acceded to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1992.[59] As of 2016, China fielded SLBMs onboard its JL-2 submarines.[65] As of February 2024, China had an estimated total inventory of approximately 500 warheads.[66]

According to Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), China is in the middle of a significant modernization and expansion of its nuclear arsenal. Its nuclear stockpile is expected to continue growing over the coming decade and some projections suggest that it will deploy at least as many intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) as either Russia or the US in that period. However, China's overall nuclear warhead stockpile is still expected to remain smaller than that of either of those states.[10] The Yearbook published by SIPRI in 2024 revealed that China's nuclear warheads stockpile increased by 90 in 2023, reaching 500 warheads.[67]

US Department of Defense officials estimate that the Chinese had more than 600 operational nuclear warheads as of December 2024, and it was on track to posess 1,000 nuclear weapons by the year 2030.[68]

States declaring possession of nuclear weapons

India

India is not a party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Indian officials rejected the NPT in the 1960s on the grounds that it created a world of nuclear "haves" and "have-nots", arguing that it unnecessarily restricted "peaceful activity" (including "peaceful nuclear explosives"), and that India would not accede to international control of their nuclear facilities unless all other countries engaged in unilateral disarmament of their own nuclear weapons. The Indian position has also asserted that the NPT is in many ways a neo-colonial regime designed to deny security to post-colonial powers.[69]

The country tested what is called a "peaceful nuclear explosive" in 1974 (which became known as "Smiling Buddha"). The test was the first test developed after the creation of the NPT, and created new questions about how civilian nuclear technology could be diverted secretly to weapons purposes (dual-use technology). India's secret development caused great concern and anger particularly from nations that had supplied its nuclear reactors for peaceful and power generating needs, such as Canada.[70] After its 1974 test, India maintained that its nuclear capability was primarily "peaceful", but between 1988 and 1990 it apparently weaponized two dozen nuclear weapons for delivery by air.[71] In 1998 India tested weaponized nuclear warheads ("Operation Shakti"), including a thermonuclear device.[72] India adopted a "no first use" policy in 1998.[73]

In July 2005, US President George W. Bush and Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh announced a civil nuclear cooperation initiative[74] that included plans to conclude an Indo-US civilian nuclear agreement. This initiative came to fruition through a series of steps that included India's announced plan to separate its civil and military nuclear programs in March 2006,[75] the passage of the India–United States Civil Nuclear Agreement by the US Congress in December 2006, the conclusion of a US–India nuclear cooperation agreement in July 2007,[76] approval by the IAEA of an India-specific safeguards agreement,[77] agreement by the Nuclear Suppliers Group to a waiver of export restrictions for India,[78] approval by the US Congress[79] and culminating in the signature of US–India agreement for civil nuclear cooperation[80] in October 2008. The US State Department said it made it "very clear that we will not recognize India as a nuclear-weapon state".[81] The United States is bound by the Hyde Act with India and may cease all cooperation with India if India detonates a nuclear explosive device. The US had further said it is not its intention to assist India in the design, construction or operation of sensitive nuclear technologies through the transfer of dual-use items.[82] In establishing an exemption for India, the Nuclear Suppliers Group reserved the right to consult on any future issues which might trouble it.[83] As of June 2024, India was estimated to have a stockpile of 172 warheads.[17][84][9]

Pakistan

Pakistan is also not a party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. Pakistan covertly developed nuclear weapons over decades, beginning in the late 1970s. Pakistan first delved into nuclear power after the establishment of its first nuclear power plant near Karachi with equipment and materials supplied mainly by western nations in the early 1970s. Pakistani Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto promised in 1971 that if India could build nuclear weapons then Pakistan would too, according to him: "We will develop Nuclear stockpiles, even if we have to eat grass."[85]

It is believed that Pakistan has possessed nuclear weapons since the mid-1980s.[86] The United States continued to certify that Pakistan did not possess such weapons until 1990, when sanctions were imposed under the Pressler Amendment, requiring a cutoff of US economic and military assistance to Pakistan.[87] In 1998, Pakistan conducted its first six nuclear tests at the Ras Koh Hills in response to the five tests conducted by India a few weeks before.

In 2004, the Pakistani metallurgist Abdul Qadeer Khan, a key figure in Pakistan's nuclear weapons program, confessed to heading an international black market ring involved in selling nuclear weapons technology. In particular, Khan had been selling gas centrifuge technology to North Korea, Iran, and Libya. Khan denied complicity by the Pakistani government or Army, but this has been called into question by journalists and IAEA officials, and was later contradicted by statements from Khan himself.[88]

As of early 2013, Pakistan was estimated to have had a stockpile of around 140 warheads,[89] and in November 2014 it was projected that by 2020 Pakistan would have enough fissile material for 200 warheads.[90] As of 2024, SIPRI estimated that Pakistan had a stockpile of around 170 warheads.[10]

North Korea

North Korea was a party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, but announced a withdrawal on 10 January 2003, after the United States accused it of having a secret uranium enrichment program and cut off energy assistance under the 1994 Agreed Framework. In February 2005, North Korea claimed to possess functional nuclear weapons, though their lack of a test at the time led many experts to doubt the claim. In October 2006, North Korea stated that, in response to growing intimidation by the United States, it would conduct a nuclear test to confirm its nuclear status. North Korea reported a successful nuclear test on 9 October 2006 (see 2006 North Korean nuclear test). Most US intelligence officials believed that the test was probably only partially successful with a yield of less than a kiloton.[91][92] North Korea conducted a second, higher-yield test on 25 May 2009 (see 2009 North Korean nuclear test) and a third test with still-higher yield on 12 February 2013 (see 2013 North Korean nuclear test).

North Korea claimed to have conducted its first hydrogen-bomb test on 5 January 2016, though measurements of seismic disturbances indicate that the detonation was not consistent with a hydrogen bomb.[93] On 3 September 2017, North Korea detonated a device, which caused a magnitude 6.1 tremor, consistent with a low-powered thermonuclear detonation; NORSAR estimates the yield at 250 kilotons[94] of TNT. In 2018, North Korea announced a halt in nuclear weapons tests and made a conditional commitment to denuclearisation of the Korean Peninsula;[95][96] however, in December 2019, it indicated it no longer considered itself bound by the moratorium.[97]

Kim Jong Un officially declared North Korea a nuclear weapons state during a speech on 9 September 2022, the country's foundation day.[98]

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), North Korea's military nuclear programme remains central to its national security strategy and it may have assembled up to 30 nuclear weapons and could produce more. North Korea conducted more than 90 ballistic missile tests during 2022, the highest number it has ever undertaken in a single year.[10]

States believed to possess nuclear weapons

Israel

Israel is generally understood to have been the sixth country to develop nuclear weapons, but does not acknowledge it. It had "rudimentary, but deliverable," nuclear weapons available as early as 1966.[99][100][101][102][103][104][6][excessive citations] Israel is not a party to the NPT. Israel engages in strategic ambiguity, saying it would not be the first country to "introduce" nuclear weapons to the Middle East without confirming or denying that it has a nuclear weapons program or arsenal. This policy of "nuclear opacity" has been interpreted as an attempt to get the benefits of deterrence with a minimal political cost.[6][7] Due to a US ban on funding countries that have weapons of mass destruction, Israel would lose around $2 billion a year in military and other aid from the US if it admitted to possessing nuclear weapons.[3]

According to the Natural Resources Defense Council and the Federation of American Scientists, Israel likely possesses around 80–400 nuclear weapons.[105][104] The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute estimates that Israel has approximately 80 intact nuclear weapons, of which 50 are for delivery by Jericho II medium-range ballistic missiles and 30 are gravity bombs for delivery by aircraft. SIPRI also reports that there was renewed speculation in 2012 that Israel may also have developed nuclear-capable submarine-launched cruise missiles.[106]

On 7 November 2023, during the Israel–Hamas war, Heritage Minister Amihai Eliyahu said during a radio interview that a nuclear strike would be "one way" to deal with Gaza, which commentators and diplomats interpreted as a tacit admission that Israel possesses such a capability. His remarks were criticized by the United States and Russia, and Eliyahu was subsequently suspended from the Israeli cabinet.[107]

Launch authority

The decision to use nuclear weapons is always restricted to a single person or small group of people. The United States and France require their respective presidents to approve the use of nuclear weapons. In the US, the Presidential Emergency Satchel is always handled by a nearby aide unless the President is near a command center. The decision rests with the Prime Minister in the United Kingdom. Information from China is unclear, but "the launch of nuclear weapons is commonly believed to rest with the Central Military Commission of the Chinese Communist Party."[citation needed] Russia grants such power to the President but may also require approval from the Minister of Defence and the Chief of the General Staff. The Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces has authority in North Korea. India, Pakistan and Israel have committees for such a decision.[108]

Some countries are known to have delegated launch authority to military personnel in the event that the usual launch authority is incapacitated; whether or not the 'pre-delegated' authority exists at any particular time is kept secret.[109] In the United States, some military commanders have been delegated authority to launch nuclear weapons "when the urgency of time and circumstances clearly does not permit a specific decision by the President."[110] Russia has a semi automated Dead Hand system which may allow military commanders to act based on certain pre-defined criteria. British nuclear-armed submarine commanders are issued with "letters of last resort" written by the Prime Minister containing secret instructions which may or may not give them delegated launch authority.[111]

Nuclear weapons sharing

Nuclear weapons shared by the United States

| Country | Base | Estimated |

|---|---|---|

| Kleine Brogel | 20 | |

| Büchel | 20 | |

| Aviano | 20 | |

| Ghedi | ||

| Volkel | 20 | |

| Incirlik | 20 | |

| 100 |

Under NATO nuclear weapons sharing, the United States has provided nuclear weapons for Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey to deploy and store.[117] This involves pilots and other staff of the "non-nuclear" NATO states practicing, handling, and delivering the US nuclear bombs, and adapting non-US warplanes to deliver US nuclear bombs. However, since all US nuclear weapons are protected with Permissive Action Links, the host states cannot easily arm the bombs without authorization codes from the US Department of Defense.[118] Former Italian President Francesco Cossiga acknowledged the presence of US nuclear weapons in Italy.[119] US nuclear weapons were also deployed in Canada as well as Greece from 1963. However, the United States withdrew three of the four nuclear-capable weapons systems from Canada by 1972, the fourth by 1984, and all nuclear-capable weapons systems from Greece by 2001.[120][121] As of April 2019[update], the United States maintained around 100 nuclear weapons in Europe, as reflected in the accompanying table.[116]

Nuclear weapons shared by Russia

| Country | Air base | Warheads |

|---|---|---|

| Probably Lida[122] | ~130 |

Since June 2023[update],[122] the leaders of Russia and Belarus have claimed that a "number of"[123] nuclear weapons are located on Belarusian territory while remaining in Russian possession.[122] Sources hostile to these countries have confirmed that nuclear warheads have been delivered to Belarus, but claim that the first transfers were instead made in August 2023.[124] Russia's stated intention is to provide Belarus with two delivery systems: dual-capable Iskander-M missile systems and necessary training and modifications for Belarusian Su-25 aircraft to carry nuclear weapons.[125]

The deployment of Russian weapons to Belarus was framed by Russian President Vladimir Putin as being equivalent to the deployments of American nuclear weapons to NATO Allies in Europe under international law.[123]

Criticism of nuclear weapons sharing

Members of the Non-Aligned Movement have called on all countries to "refrain from nuclear sharing for military purposes under any kind of security arrangements."[126] The Institute of Strategic Studies Islamabad (ISSI) has criticized the arrangement for allegedly violating Articles I and II of the NPT, arguing that "these Articles do not permit the NWS to delegate the control of their nuclear weapons directly or indirectly to others."[127] NATO has argued that the weapons' sharing is compliant with the NPT because "the US nuclear weapons based in Europe are in the sole possession and under constant and complete custody and control of the United States."[128]

States formerly possessing nuclear weapons

Nuclear weapons have been present in many nations, often as staging grounds under control of other powers. However, in only one instance has a nation given up nuclear weapons after being in full control of them. The fall of the Soviet Union left several former Soviet republics in physical possession of nuclear weapons, although not operational control which was dependent on Russian-controlled electronic Permissive Action Links and the Russian command and control system.[129][130] Of these, Kazakhstan and Ukraine continue to have neither their own nuclear weapons nor another state's nuclear weapons stationed in their territory whereas Belarus does again claim to have Russian-owned nuclear weapons stationed on its territory since 2023.

South Africa

South Africa produced six nuclear weapons in the 1980s, but dismantled them in the early 1990s.

In 1979, there was a detection of a putative covert nuclear test in the Indian Ocean, called the Vela incident. It has long been speculated that it was a test by Israel, in collaboration with and with the support of South Africa, though this has never been confirmed. South Africa could not have constructed such a nuclear bomb by itself until November 1979, two months after the "double flash" incident.[132]

South Africa acceded to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1991.[133][134]

Former Soviet republics

- Kazakhstan had 1,400 Soviet-era nuclear weapons on its territory and transferred them all to Russia by 1995, after Kazakhstan acceded to the NPT.[135]

- Ukraine had as many as 3,000 nuclear weapons deployed on its territory when it became independent from the Soviet Union in 1991, equivalent to the third-largest nuclear arsenal in the world.[citation needed] At the time Ukraine acceded to the NPT in December 1994, Ukraine had agreed to dispose of all nuclear weapons within its territory. The warheads were removed from Ukraine by 1996 and disassembled in Russia.[136] Despite Russia's subsequent and internationally disputed annexation of Crimea in 2014, Ukraine reaffirmed its 1994 decision to accede to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty as a non-nuclear-weapon state.[137]

- Belarus, which since 2023 has resumed hosting Russian nuclear weapons, also had single warhead missiles stationed on its territory into the 1990s while a constituent of the Soviet Union. When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, 81 single warhead missiles were stationed on newly Belarusian territory, but were all transferred to Russia by 1996. Belarus was a member of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) from May 1992[138] through February 2022, when it held a constitutional referendum resulting in the cessation of its non-nuclear status.[139]

In connection with their accession to the NPT, all three countries received assurances that their sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity would be respected, as stated in the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances. These assurances have been flouted by Russia since the Russo-Ukrainian War began in 2014, during which Russia claimed to annex Crimea, occupied Eastern Ukraine, and in 2022, launched a full-scale invasion, with limited responses by the other signatories.[140][141][142]

Stationed countries

Up until the 1990s the US had stationed nuclear weapons outside of its territories and sharing countries.[143]

South Korea

Philippines

During the Cold War, specifically during the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos from 1965 to 1986, American nuclear warheads were secretly stockpiled in the Philippines.[144][145]

Taiwan

Taiwan was developing capacities to construct nuclear weapons up until 1988.[146][147] Before 1974, the United States stationed some of its arsenal in Taiwan.[148]

Japan

After World War II the US had nuclear weapons stationed in Japan until the 1970s.

Canada

The US stationed nuclear weapons at CFB Goose Bay in Labrador between 1964 and 1984.[149]

Greece

The US stationed nuclear weapons in Greece until they were removed in 2001.[150]

See also

- Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty

- Doomsday Clock

- Historical nuclear weapons stockpiles and nuclear tests by country

- International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons

- No first use

- Nuclear disarmament

- Nuclear latency

- Nuclear power

- Nuclear program of Iran

- Nuclear proliferation

- Nuclear terrorism

- Nuclear warfare

- Nuclear-weapon-free zone

Notes

- ^ Estimates from the Federation of American Scientists. The latest update was in January 2023. "Deployed" indicates the total of deployed strategic and non-strategic warheads. Because the number of non-strategic warheads is unknown for many countries, this number should be taken as a minimum. When a range of weapons is given (e.g., 0–10), it generally indicates that the estimate is being made on the amount of fissile material that has likely been produced, and the amount of fissile material needed per warhead depends on estimates of a country's proficiency at nuclear weapon design.

- ^ As a part of the Soviet Union. The Russian Federation has not tested a nuclear weapon since 1991.

- ^ See also UK Trident programme. From the 1960s until the 1990s, the United Kingdom's Royal Air Force maintained the independent capability to deliver nuclear weapons via its V bomber fleet.

- ^ See also Force de dissuasion. France formerly possessed a nuclear triad until 1996, when its land-based arsenal was retired.

- ^ Data include the suspected Vela incident of 22 September 1979.[39]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h "World Nuclear Forces, SIPRI yearbook 2020". Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. January 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ Murdock, Clark A.; Miller, Franklin; Mackby, Jenifer (13 May 2010). "Trilateral Nuclear Dialogues Role of P3 Nuclear Weapons Consensus Statement". Center for Strategic and International Studies. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- ^ a b Harding, Luke (12 December 2006). "Calls for Olmert to resign after nuclear gaffe Israel and the Middle East". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 15 May 2009.

- ^ Nuclear Forces Archived 7 January 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, sipri.org

- ^ There are a wide range of estimates as to the size of the Israeli nuclear arsenal. For a compiled list of estimates, see Avner Cohen, The Worst-Kept Secret: Israel's bargain with the Bomb (Columbia University Press, 2010), Table 1, page xxvii and page 82.

- ^ a b c NTI Israel Profile Archived 28 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 12 July 2007.

- ^ a b Avner Cohen (2010). The Worst-Kept Secret: Israel's bargain with the Bomb. Columbia University Press.

- ^ Arms Control and Global Security, Paul R. Viotti – 2010, p 312

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Kristensen, Hans M. (2023). "Status Of World Nuclear Forces". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 79 (1): 28–52. Bibcode:2023BuAtS..79a..28K. doi:10.1080/00963402.2022.2156686. ISSN 0096-3402. S2CID 255826288.

- ^ a b c d Kristensen, Hans M; Korda, Matt. (2023). "World Nuclear Forces 2023". In SIPRI Yearbook 2023: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security.Oxford University Press.

- ^ "Nuclear club", Oxford English Dictionary: "nuclear club n. the nations that possess nuclear weapons." The term's first cited usage is from 1957.

- ^ Jane Onyanga-Omara, "The Nuclear Club: Who are the 9 members?" Archived 4 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine, USA TODAY, 6 January 2016

- ^ Webster, Paul (July/August 2003). "Nuclear weapons: how many are there in 2009 and who has them? Archived 2017-01-08 at the Wayback Machine" The Guardian, 6 September 2009.

- ^ "Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons". Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ "Status of Signature and Ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty". Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ "The Nuclear Testing Tally". www.armscontrol.org. Arms Control Association. August 2022. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ a b c "Role of nuclear weapons grows as geopolitical relations deteriorate—new SIPRI Yearbook out now | SIPRI". www.sipri.org. 17 June 2024. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ a b IISS 2012, pp. 54–55

- ^ Kristensen, Hans M.; Korda, Matt; Reynolds, Eliana (4 May 2023). "Russian nuclear weapons, 2023". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 79 (3): 174–199. Bibcode:2023BuAtS..79c.174K. doi:10.1080/00963402.2023.2202542. ISSN 0096-3402. S2CID 258559002.

- ^ "Putin revokes Russia's ratification of nuclear test ban treaty". Reuters. 2 November 2023. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Nuclear Weapons: Who Has What at a Glance". Arms Control Association. July 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

India, Israel, and Pakistan never signed the NPT and possess nuclear arsenals.

- ^ IISS 2012, p. 169

- ^ Kristensen, Hans M.; Korda, Matt; Johns, Eliana (4 July 2023). "French nuclear weapons, 2023". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 79 (4): 272–281. Bibcode:2023BuAtS..79d.272K. doi:10.1080/00963402.2023.2223088. ISSN 0096-3402. S2CID 259938405.

- ^ IISS 2012, p. 111

- ^ Kristensen, Hans M.; Korda, Matt; Reynolds, Eliana (4 March 2023). "Chinese nuclear weapons, 2023". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 79 (2): 108–133. Bibcode:2023BuAtS..79b.108K. doi:10.1080/00963402.2023.2178713. ISSN 0096-3402. S2CID 257498038.

- ^ The Long Shadow: Nuclear Weapons and Security in 21st Century Asia by Muthiah Alagappa (NUS Press, 2009), page 169: "China has developed strategic nuclear forces made up of land-based missiles, submarine-launched missiles, and bombers. Within this triad, China has also developed weapons of different ranges, capabilities, and survivability."

- ^ IISS 2012, pp. 223–224

- ^ Kristensen, Hans M.; Korda, Matt (4 July 2022). "Indian nuclear weapons, 2022". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 78 (4): 224–236. Bibcode:2022BuAtS..78d.224K. doi:10.1080/00963402.2022.2087385. ISSN 0096-3402. S2CID 250475371.

- ^ IISS 2012, p. 243

- ^ "Now, India has a nuclear triad". The Hindu. 18 October 2016. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2016.

- ^ Peri, Dinakar (12 June 2014). "India's Nuclear Triad Finally Coming of Age". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 9 April 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ "Nuclear triad weapons ready for deployment: DRDO". 7 July 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 10 March 2015.

- ^ Kristensen, Hans M.; Korda, Matt (3 September 2021). "Pakistani nuclear weapons, 2021". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 77 (5): 265–278. Bibcode:2021BuAtS..77e.265K. doi:10.1080/00963402.2021.1964258. ISSN 0096-3402. S2CID 237434295.

- ^ Tellis, Ashley (2022). "Striking Asymmetries: Nuclear Transitions in Southern Asia" (PDF). Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. p. 168. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 May 2023. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

On such premises, Pakistan's nuclear arsenal in 2020 would consist of between 243 and 283 nuclear devices.

- ^ Mizokami, Kyle (26 November 2021). "How Pakistan Developed Its Own Nuclear Triad". The National Interest. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ "Babur (Hatf 7)". Missile Threat. Retrieved 8 July 2023.

- ^ Kristensen, Hans M.; Korda, Matt (2 January 2022). "Israeli nuclear weapons, 2021". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 78 (1): 38–50. Bibcode:2022BuAtS..78a..38K. doi:10.1080/00963402.2021.2014239. ISSN 0096-3402. S2CID 246010705.

- ^ Farr, Warner D (September 1999), The Third Temple's holy of holies: Israel's nuclear weapons, The Counterproliferation Papers, Future Warfare Series 2, USAF Counterproliferation Center, Air War College, Air University, Maxwell Air Force Base, retrieved 2 July 2006.

- ^ *Hersh, Seymour (1991). The Samson option: Israel's Nuclear Arsenal and American Foreign Policy. Random House. ISBN 978-0-394-57006-8., page 271

- ^ An Atlas of Middle Eastern Affairs By Ewan W. Anderson, Liam D. Anderson, (Routledge 2013), page 233: "In terms of delivery systems, there is strong evidence that Israel now possesses all three elements of the nuclear triad."

- ^ IISS 2012, p. 328

- ^ Kristensen, Hans M.; Korda, Matt (3 September 2022). "North Korean nuclear weapons, 2022". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 78 (5): 273–294. Bibcode:2022BuAtS..78e.273K. doi:10.1080/00963402.2022.2109341. ISSN 0096-3402. S2CID 252132124.

- ^ "U.S.: Test Points to N. Korea Nuke Blast". The Washington Post. 13 October 2006. Archived from the original on 27 December 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons: Declarations, statements, reservations and notes

- ^ CSIS 2022

- ^ Nichols, Kenneth D. (1987). The Road to Trinity. New York: William Morrow and Company. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-688-06910-X. OCLC 15223648.

- ^ "Atomic Bomb Seen as Cheap at Price". Edmonton Journal. 7 August 1945. p. 1. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Hansen, Chuck (1988). U.S. nuclear weapons: The secret history. Arlington, TX: Aerofax. ISBN 978-0-517-56740-1.

- ^ Hansen, Chuck (1995). The Swords of Armageddon: U.S. nuclear weapons development since 1945. Sunnyvale, CA: Chukelea Publications. Archived from the original on 30 December 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ Stephen I. Schwartz, ed., Atomic Audit: The Costs and Consequences of U.S. Nuclear Weapons Since 1940 (Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 1998).

- ^ Gross, Daniel A. (2016). "An Aging Army". Distillations. Vol. 2, no. 1. pp. 26–36. Archived from the original on 20 March 2018. Retrieved 22 March 2018.

- ^ "Fact Sheet: Increasing Transparency in the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Stockpile" (PDF). U.S. Department of Defense. 3 May 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- ^ "Policy Library". Archived from the original on 22 August 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ^ a b Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen, "Global nuclear stockpiles, 1945–2006," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists 62, no. 4 (July/August 2006), 64–66...

- ^ Holloway, David (1994). Stalin and the bomb: The Soviet Union and atomic energy, 1939–1956. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-06056-0.

- ^ Gowing, Margaret (1974). Independence and deterrence: Britain and atomic energy, 1945–1952. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-15781-7.

- ^ Arnold, Lorna (2001). Britain and the H-bomb. Basingstoke: Palgrave. ISBN 978-0-312-23518-5.

- ^ a b Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons Archived 17 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs.

- ^ France 'would use nuclear arms' Archived 19 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine (BBC, January 2006)

- ^ "Nuclear deterrent important in 'dangerous world', says Hollande". spacedaily.com. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ^ John Wilson Lewis and Xue Litai, China Builds the Bomb (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 1988). ISBN 0-8047-1452-5

- ^ "No-First-Use (NFU)". Nuclear Threat Initiative. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010.

- ^ Statement on security assurances issued on 5 April 1995 by the People's Republic of China (PDF) (Report). United Nations. 6 April 1995. S/1995/265. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ Kristensen, Hans M.; Korda, Matt (4 July 2019). "Chinese nuclear forces, 2019". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 75 (4): 171–178. Bibcode:2019BuAtS..75d.171K. doi:10.1080/00963402.2019.1628511. ISSN 0096-3402.

- ^ Chinese Nuclear Forces, 2024: A “Significant Expansion”, Federation of American Scientists, January 16, 2024.

- ^ "Chinese Nuclear Arsenal Grows by Seventeen Percent in 2022, SIPRI Reports". Retrieved 21 June 2023.

- ^ McLeary, Paul (18 December 2024). "Pentagon report: China boosts nuclear stockpile". Politico. Retrieved 18 December 2024.

- ^ George Perkovich, India's Nuclear Bomb: The Impact on Global Proliferation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 120–121, and 7.

- ^ "18 MAY 1974 – SMILING BUDDAH". CTBTO. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ George Perkovich, India's Nuclear Bomb: The Impact on Global Proliferation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999), 293–297.

- ^ "India's Nuclear Weapons Program: Operation Shakti". 1998. Archived from the original on 3 October 2006. Retrieved 10 October 2006.

- ^ "No first use nuclear policy: Explained". The Times of India. 29 August 2019. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 19 April 2023.

- ^ "Joint Statement Between President George W. Bush and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on 27 December 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2009 – via National Archives.

- ^ "Implementation of the India-United States Joint Statement of July 18, 2005: India's Separation Plan" (PDF). 3 September 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2006.

- ^ "U.S.- India Civil Nuclear Cooperation Initiative – Bilateral Agreement on Peaceful Nuclear Cooperation". 27 July 2007. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ "IAEA Board Approves India-Safeguards Agreement". Iaea.org. 31 July 2008. Archived from the original on 5 May 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2009.

- ^ "Statement on Civil Nuclear Cooperation with India" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ "Congressional Approval of the U.S.-India Agreement for Cooperation Concerning Peaceful Uses of Nuclear Energy (123 Agreement)". 2 October 2008. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ "Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and Indian Minister of External Affairs Pranab Mukherjee At the Signing of the U.S.-India Civilian Nuclear Cooperation Agreement". 10 October 2008. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Interview With Undersecretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Robert Joseph Archived 23 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Arms Control Today, May 2006.

- ^ Was India misled by America on nuclear deal? Archived 10 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Indian Express.

- ^ "ACA: Final NSG Statement" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 November 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2008.

- ^ "India and Pakistan". Center for Arms Control and Non-Proliferation. Retrieved 16 September 2023.

- ^ Sublettle, Carey (15 October 1965). "Historical Background: Zulfikar Ali Bhutto". Nuclear weapons archives. Federation of American Scientists (FAS). Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ NTI Pakistan Profile Archived 16 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ "Case Studies in Sanctions and Terrorism: Pakistan". Iie.com. Archived from the original on 12 May 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2009.

- ^ See A.Q. Khan: Investigation, dismissal, confession, pardon and aftermath, for citations and details.

- ^ "Status of World Nuclear Forces". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 24 January 2018. Retrieved 24 January 2018.

- ^ "Pakistan to Have 200 Nuke Weapons by 2020: US Think Tank". The Times of india. November 2014. Archived from the original on 27 November 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Gladstone, Rick; Jacquette, Rogene (18 February 2017). "How the North Korean Nuclear Threat Has Grown". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via NYTimes.com.

- ^ "TIMELINE:North Korea: climbdowns and tests". Reuters. 25 May 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2021 – via www.reuters.com.

- ^ "North Korea Test Shows Technical Advance". The Wall Street Journal. Vol. CCLXVII, no. 5. 7 January 2016. p. A6.

- ^ "The nuclear explosion in North Korea on 3 September 2017: A revised magnitude assessment". NORSAR.no. Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 15 September 2017.

- ^ "North Korea has Begun Dismantlement of the Punggye-ri Nuclear Test Site'". 38north.org. Archived from the original on 3 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ "'Destruction at North Korea's Nuclear Test Site: A Review in Photos'". 38north.org. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- ^ Sang-Hun, Choe (31 December 2019). "North Korea Is No Longer Bound by Nuclear Test Moratorium, Kim Says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- ^ "North Korea declares itself a nuclear weapons state, in 'irreversible' move". CNN. 9 September 2022. Retrieved 9 September 2022.

- ^ Cohen, Avner (1998), Israel and the Bomb, New York: Columbia University Press, p. 1, ISBN 978-0-231-10482-1

- ^ ElBaradei, Mohamed (27 July 2004). "Transcript of the Director General's Interview with Al-Ahram News". International Atomic Energy Agency. Archived from the original on 18 April 2012. Retrieved 3 June 2007.

- ^ "Nuclear Overview". Israel. NTI. Archived from the original (profile) on 2 January 2009. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ^ My Promised Land, by Ari Shavit, (London 2014), page 188

- ^ Nuclear Proliferation International History Project (28 June 2013). "Israel's Quest for Yellowcake: The Secret Argentina-Israel Connection, 1963–1966". Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017.

- ^ a b "Nuclear Weapons". fas.org. Archived from the original on 7 December 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ There are a wide range of estimates as to the size of the Israeli nuclear arsenal. For a compiled list of estimates, see Avner Cohen, The Worst-Kept Secret: Israel's bargain with the Bomb (Columbia University Press, 2010), Table 1, page xxvii and page 82.

- ^ "Israel". Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "Israel's nuclear option remark raises 'huge number of questions': Russia's foreign ministry says Israel appeared to have admitted that it has nuclear weapons and is willing to use them". Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera America. Retrieved 17 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Whose Finger Is On the Button?" (PDF). Union of Concerned Scientists. December 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Feaver, Peter; Geers, Kenneth (16 October 2017). ""When the Urgency of Time and Circumstances Clearly Does Not Permit . . .": Pre-delegation in Nuclear and Cyber Scenarios". Carnegie Endowment.

- ^ "MILITARY GOT AUTHORITY TO USE NUCLEAR ARMS IN 1957". Washington Post. 8 January 2024. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 3 October 2024.

- ^ Taylor, Adam (13 July 2016). "Every new British prime minister pens a handwritten 'letter of last resort' outlining nuclear retaliation". Washington Post.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Whose Finger Is on the Button? | Union of Concerned Scientists". www.ucsusa.org. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- ^ Mikhail Tsypkin (September 2004). "Adventures of the "Nuclear Briefcase"". Strategic Insights. 3 (9). Archived from the original on 23 September 2004.

- ^ Alexander Golts (20 May 2008). "A 2nd Briefcase for Putin". Moscow Times. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011.

- ^ "N. Korea adopts nuclear use manual, signaling return to parallel pursuit of nukes, economy". english.hani.co.kr. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ a b Hans M. Kristensen; Matt Korda (26 January 2021). "United States nuclear weapons, 2021". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 77 (1): 43–63. doi:10.1080/00963402.2020.1859865. ISSN 0096-3402. Wikidata Q105699219.

About 100 of these (versions −3 and −4) are thought to be deployed at six bases in five European countries: Aviano and Ghedi in Italy; Büchel in Germany; Incirlik in Turkey; Kleine Brogel in Belgium; and Volkel in the Netherlands. This number has declined since 2009 partly due to reduction of operational storage capacity at Aviano and Incirlik (Kristensen 2015, 2019c). ... Concerns were raised about the security of the nuclear weapons at the Incirlik base during the failed coup attempt in Turkey in July 2016, and the chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee for Europe stated in September 2020 that "our presence, quite honestly, in Turkey is certainly threatened," and further noted that "we don't know what's going to happen to Incirlik" (Gehrke 2020). Despite rumors in late 2017 that the weapons had been "quietly removed" (Hammond 2017), reports in 2019 that US officials had reviewed emergency nuclear weapons evacuation plans (Sanger 2019) indicated that that there were still weapons present at the base. The numbers appear to have been reduced, however, from up to 50 to approximately 20.

- ^ "Berlin Information-center for Transatlantic Security: NATO Nuclear Sharing and the N.PT – Questions to be Answered". Bits.de. Archived from the original on 19 May 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2009.

- ^ "Nuclear Command and Control" (PDF). Security Engineering: A Guide to Building Dependable Distributed Systems. Ross Anderson, University of Cambridge Computing Laboratory. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ^ "Cossiga: "In Italia ci sono bombe atomiche Usa"". Archived from the original on 28 September 2015. Retrieved 16 September 2015.

- ^ Weapons of Mass Debate - Greece: a Key Security Player for both Europe and NATO, Institut Montaigne, 7 December 2001]

- ^ Hans M. Kristensen (February 2005). U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe (PDF) (Report). Natural Resources Defense Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 July 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2006.

- ^ a b c Kristensen, Hans; Korda, Matt (30 June 2023). "Russian Nuclear Weapons Deployment Plans in Belarus: Is There Visual Confirmation?". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ a b Faulconbridge, Guy (6 July 2023). "Lukashenko: I have veto over use of Russian nuclear weapons in Belarus". Reuters. Retrieved 17 July 2023.

- ^ Borysenko, Ivan. "Russia delivers first nuclear warheads to Belarus - Budanov". The New Voice of Ukraine. NV. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ "Russian Foreign Ministry Announces Conversion of Belarusian Su-25 Aircraft to Carry Nuclear Weapons". eurointegration.com. European Pravada. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Statement on behalf of the non-aligned state parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, 2 May 2005

- ^ ISSI – NPT in 2000: Challenges ahead, Zafar Nawaz Jaspal, The Institute of Strategic Studies, Islamabad Archived 9 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "NATO's Positions Regarding Nuclear Non-Proliferation, Arms Control and Disarmament and Related Issues" (PDF). NATO. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- ^ William C. Martel (1998). "Why Ukraine gave up nuclear weapons : nonproliferation incentives and disincentives". In Barry R. Schneider, William L. Dowdy (ed.). Pulling Back from the Nuclear Brink: Reducing and Countering Nuclear Threats. Psychology Press. pp. 88–104. ISBN 9780714648569. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ Alexander A. Pikayev (Spring–Summer 1994). "Post-Soviet Russia and Ukraine: Who can push the Button?" (PDF). The Nonproliferation Review. 1 (3): 31–46. doi:10.1080/10736709408436550. ISSN 1073-6700. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 May 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- ^ Lewis, Jeffrey (3 December 2015). "Revisiting South Africa's Bomb". Arms Control Wonk. Leading Voice on Arms Control, Disarmament and Non-Proliferation. Archived from the original on 6 December 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- ^ McGreal, Chris (24 May 2010). "Revealed: how Israel offered to sell South Africa nuclear weapons". The Guardian. Washington, D.C. Retrieved 6 February 2022.

- ^ Nuclear Weapons Program (South Africa) Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Federation of American Scientists (29 May 2000).

- ^ Von Wielligh, N. & von Wielligh-Steyn, L. (2015). The Bomb – South Africa's Nuclear Weapons Programme. Pretoria: Litera.

- ^ "Kazakhstan Special Weapons". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ "Ukraine Special Weapons". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ Joint Statement by the United States and Ukraine Archived 16 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, 25 March 2014.

- ^ "Belarus Special Weapons". Federation of American Scientists. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- ^ "Belarus votes to give up non-nuclear status". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Borda, Aldo Zammit (2 March 2022). "Ukraine war: what is the Budapest Memorandum and why has Russia's invasion torn it up?". The Conversation. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ Pifer, Steven (12 April 2014). "The Budapest Memorandum and U.S. Obligations". Brookings Institution. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine's forgotten security guarantee: The Budapest Memorandum". Deutsche Welle. 12 May 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2022.

- ^ Hans M. Kristensen (28 September 2005). "The Withdrawal of U.S. Nuclear Weapons From South Korea". Federation of American Scientists. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- ^ US stored nukes in Philippines under Marcos–Bayan, 15 April 2024

- ^ "Presidential Decision on Categories of Information for Symington Subcommittee to be protected by executive privilege" (PDF). Retrieved 15 April 2024.

- ^ Albright, David; Stricker, Andrea (2018). Taiwans's Former Nuclear Weapons Program: Nuclear Weapons On-Demand (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Institute for Science and International Security. ISBN 978-1-72733-733-4. LCCN 2018910946. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2024.

- ^ "ROC Chief of the General Staff, General Hau Pei-tsun, met the director of American Institute in Taiwan, David Dean in his office after Colonel Chang's defection in 1988. Dean questioned him with the US satellite imagery detecting a minimized nuclear explosion at the Jioupeng military test field in Pingtung in 1986. Hao answered that, after nearly 20 years of research, ROC had successfully produced a controlled nuclear reaction. Hau recorded the statement in his diary and published on the Issue 1 (2000), but was removed from the later re-issues." Hau, Pei-tsun (1 January 2000). Ba nian can mou zong zhang ri ji [8-year Diary of the Chief of the General Staff (1981–1989)] (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Taipei: Commonwealth Publishing. ISBN 9576216389. OL 13062852M.

- ^ Norris, Robert S.; Arkin, William M.; Burr, William (20 October 1999). "United States Secretly Deployed Nuclear Bombs In 27 Countries and Territories During Cold War". National Security Archive. National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book. No. 20. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original on 7 February 2021.

- ^ Noakes, Taylor C. "Canada and Nuclear Weapons". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 January 2024.

- ^ "Greece". ICAN. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

Bibliography

- International Institute for Strategic Studies (7 March 2012). Hackett, James (ed.). The Military Balance 2012. London, England: Routledge. ISBN 978-1857436426.

- Farr, Warner D. (September 1999), The Third Temple's holy of holies: Israel's nuclear weapons, The Counterproliferation Papers, Future Warfare Series, vol. 2, USAF Counterproliferation Center, Air War College, Air University, Maxwell Air Force Base, retrieved 2 July 2006.

- Philipp C. Bleek, “When Did (and Didn’t) States Proliferate? Chronicling the Spread of Nuclear Weapons,” Discussion Paper (Cambridge, MA: Project on Managing the Atom, Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, June 2017).

External links

- The Nuclear Weapon Archive

- Nuclear Notebook from Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

- U.S. Nuclear Weapons in Europe: A review of post-Cold War policy, force levels, and war planning NRDC, February 2005

- Tracking Nuclear Proliferation Online NewsHour with Jim Lehrer

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute's data on world nuclear forces

- Nuclear Proliferation International History Project For more on the history of nuclear proliferation see the Woodrow Wilson Center's Nuclear Proliferation International History Project website.

- Proliferation Watch: US Intelligence Assessments of Potential Nuclear Powers, 1977–2001