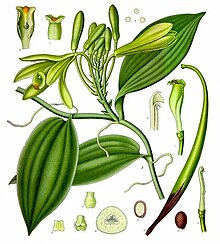

Vanilla planifolia

| Vanilla planifolia | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1887 illustration from Köhler's Medicinal Plants | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Order: | Asparagales |

| Family: | Orchidaceae |

| Subfamily: | Vanilloideae |

| Genus: | Vanilla |

| Species: | V. planifolia

|

| Binomial name | |

| Vanilla planifolia | |

| Synonyms[4] | |

| |

Vanilla planifolia is a species of vanilla orchid native to Mexico, Central America, Colombia, and Brazil.[2] It is one of the primary sources for vanilla flavouring, due to its high vanillin content. Common names include flat-leaved vanilla,[5] and West Indian vanilla (also used for the Pompona vanilla, V. pompona). Often, it is simply referred to as vanilla.[6] It was first scientifically named in 1808. With the species' population in decline and its habitats being converted to other purposes, the IUCN has assessed Vanilla planifolia as Endangered.[1]

Description

[edit]Vanilla planifolia grows as an evergreen vine, either on the ground or on trees.[7] It will sometimes grow as an epiphyte without rooting in the soil. When rooted in the soil its terrestrial roots are branched and develop fine root hairs associated with mycorrhizal fungus.[8] In the wild it easily grows to 15 meters in length,[9] and may grow to as much as 30 meters.[2] When growing in full shade the vine will very seldom branch, but when in sunlight it will develop multiple branches. Younger parts of the vine, well attached to their support, will have a zig-zag structure with an angle of about 120° at each node.[10] To cling to trees or other surfaces it has thick, fleshy aerial roots that develop from the nodes.[7] These aerial support roots almost never branch and are only present on younger parts of the vine while the older parts of the vine will hang down through the canopy to the forest floor.[10] On the nodes opposite the root nodes it has a single flat bladed succulent leaf.[5] When full grown the glossy, bright green leaves are 8–25 cm in length and 2–8 cm wide, lanceolate to oval in shape with a pointed tip. Leaves last for three to four years if not damaged.[8]

Flowers

[edit]

The flowers come from an axillary cluster that will have 12–20 buds.[7] The flowers are greenish-yellow, with a diameter of 5 cm (2 in) and only have a slight scent.[5] The flowers require pollination to set fruit, but open in the morning and usually fade in rising temperatures of the same afternoon.[7] Though each flower lasts only one day, the flowering of Vanilla planifolia takes place over a period of two months once a year.[8] In the native lowland forest habitat flowering takes place in April and May towards the end of the dry season.[1] The plants are self-fertile, and pollination simply requires a transfer of the pollen from the anther to the stigma, but have a structure to prevent this from happening without intervention.[11] In the wild, there is only around a 1% chance that the flowers will be pollinated.[12]

Fruit

[edit]

Fruit is produced only on mature plants. This takes 2-3 years for meter long cuttings and 3-4 years for 12 in cuttings or tissue cultures. The fruits are 15–23 cm (6–9 in) long pods (often incorrectly called beans). Outwardly they resemble small bananas. They mature after about eight to nine months.[8]

Taxonomy

[edit]The first scientific description of Vanilla planifolia was published by Henry Charles Andrews in the eighth volume of his The Botanist's Repository.[2] In his description he credits Charles Plumier as having published a description of it in 1703 as the third species of the genus Vanilla. He created the drawing in his book from a specimen that bloomed in a hothouse belonging to Charles Greville.[13]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]Vanilla planifolia is a native of the neotropical realm, from southern Mexico through Central America, Colombia, and the northern portions of Brazil.[12][2] Previously it had been thought to be native to just southern Mexico and Belize.[14][1] Because of cultivation it has additionally spread to a number of tropical areas including south Florida, the Cayman Islands, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, tropical portions of Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela, French Guiana, Suriname, and Guyana in the Americas. It is also recorded as growing in Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, Comoros, Bangladesh, the Malay Peninsula, the island of Java, the Chagos Archipelago, Cook Island, the Island of New Guinea, and New Caledonia.[2]

Vanilla planifolia requires a humid, warm tropical climate and grows best between 20 and 30 °C (68 and 86 °F) in humid conditions. It can only accept a minimum of 10 °C (50 °F) and a maximum of 33 °C (91 °F). Minimum rainfall requirements are about 2000 mm per year.[10] For good growth it also needs a soil with plenty of available calcium and potassium. It also prefers well-draining soils and a pH between 6.0 and 7.0.[15] The natural altitude range is from 150 to 900 meters. To trigger flowering it requires a dry period in the spring.[1]

Due to human land uses for crops and timber the required habitat for Vanilla planifolia has become very reduced and fragmented. The number of mature individuals in the wild is declining and the amount of suitable habitat also continues to decline. The IUCN assessed it as endangered in 2017, publishing it in 2020.[1]

Ecology

[edit]In its native habitat Vanilla planifolia depends on one or more pollinators. Several species of bee have been proposed including Euglossa species, Eulaema cingulata, Eulaema polychroma, Eulaema meriana, and Melipona beecheii for pollination.[5] However, no definitive observation of pollination is recorded and the size of M. beecheii in particular make it unlikely to be a pollinator of this species of orchid,[16] though unpublished observations suggest that Euglossa (reported as E. viridissima, but this species has historically been confused with other Euglossa species[17]) might be capable of completing pollination.[18] Attempts to document the visitation of V. planifolia in the Yucatan peninsula of Mexico failed to record any visitation by any stingless bees or orchid bees (including Melipona, Eulaema, and Euglossa), leaving the identity of natural pollinators as yet unresolved.[19]

Though the seeds of Vanilla planifolia are very small, they are relatively large for an orchid and are not dispersed by the wind. Instead they spread through the rain forest habitat by many different animals.[20] Male orchid bees in the tribe Euglossini in the genera Euglossa and Eulaema exhibit fragrance collecting behavior with the fruits. Specific species observed removing seeds as part of this behavior include Euglossa bursigera, Euglossa ignita, Euglossa tridentata, and Eulaema cingulata. Conversely female stingless bees remove the pulp of fruit in a behavior consistent with nest building activities. The two species observed distributing V. planifolia seeds this way are Eulaema polychroma and Scaptotrigona subobscuripennis.[20] Seeds being distributed by bees is a rare behavior and has only been documented in three species of tropical trees previously, the cadaghi Corymbia torelliana, Coussapoa asperifolia subsp. magnifolia, and Zygia racemosa. Both rodents and marsupials are confirmed to consume fallen pods on the forest floor. The specific species observed eating the pods include Tome's spiny rat (Proechimys semispinosus) and the common opossum (Didelphis marsupialis). Further experiments by the team led by Dr Adam Karremans showed that seeds were viable after being passed through the gut, but it did not increase or decrease germination significantly.[20]

Chemistry

[edit]The major chemical components from the pods are vanillin, vanillic acid, 4-hydroxybenzaldehyde and 4-hydroxybenzoic acid.[21] Vanillin makes up 80% of the total aromatic compounds found in the pods, in contrast to the 50% content of Vanilla × tahitensis pods. Some of the other chemicals found in lesser amounts in the pods of Vanilla planifolia such as guaiacol, 4-methylguaiacol, acetovanilone, and vanillic alcohol also contribute to the perception of a vanilla flavor.[11]Vanilla planifolia is notable for its role in vanilla production. The enzyme β-glucosidase is crucial in the release of vanillin during the curing process, which is essential for producing high-quality vanilla flavor.[22]

Contact dermatitis

[edit]The sap of most species of Vanilla orchid which exudes from cut stems or where pods are harvested can cause moderate to severe dermatitis if it comes in contact with bare skin, though it is water-soluble and can be removed by washing. The sap of vanilla orchids contains calcium oxalate crystals, which appear to be the main causative agent of contact dermatitis in vanilla plantation workers.[2][23]

Cultivation

[edit]

Vanilla planifolia has been propagated clonally through cuttings rather than from seeds and selective breeding.[24] As of 2023 there is only one patented cultivar, "Handa", and very few other named cultivars. The most important of these cultivars for commercial growing are the "Mansa" types. There are also two variegated cultivars sold for ornamental gardening.[8] Though there are five known attempted introductions to Reunion Island between 1793 and 1875, only the 1822 introduction was successful. It is likely that almost all the vanilla grown in the areas surrounding the Indian Ocean are descended from this one introduction and this is supported by modern genetic research. Vanilla as a crop could be threatened by this genetic bottleneck and the subsequent buildup of negative mutations.[24]

Because of the low rate of pollination, even in areas with pollinators, and rare to nonexistent elsewhere, the flowers must be hand-pollinated when grown on farms. Once beans in a cluster turn yellow and ripe, the whole cluster is generally harvested and cured. Curing involves fermentation and drying of the pod to develop the characteristic vanilla flavor while minimizing the loss of essential oils. Vanilla extract is obtained from this portion of the plant.[8]

It is cultivated and harvested primarily in Veracruz, Mexico, Tahiti, Indonesia, and Madagascar.[25]

V. planifolia can be grown and harvested indoors as a houseplant or in a greenhouse, but it has very precise requirements for growing conditions. It is generally only attempted by experts in orchid cultivation.[26]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Vega, M.; Hernández, M.; Herrera-Cabrera, B.E.; Wegier, A. (2020). "Vanilla planifolia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T103090930A172970359. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T103090930A172970359.en. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g POWO (2023). "Vanilla planifolia Andrews". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ "Vanilla planifolia Andrews". Catalogue of Life. Species 2000. n.d. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ The Plant List: A Working List of All Plant Species, retrieved 26 January 2016

- ^ a b c d "Vanilla planifolia (Commercial Vanilla, Flat Leaved Vanilla)". Go Orchids. North American Orchid Conservation Center. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ "Vanilla planifolia". Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Vanilla planifolia". Missouri Botanical Garden Plant Finder. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Chambers, Alan; Moon, Pamela; De Verlands Edmond, Vovener; Brym, Maria; Bassil, Elias; Wu, Xingbo (27 January 2023). "Vanilla Cultivation in Southern Florida: HS1348, rev. 1/2023". EDIS. 2023 (1). doi:10.32473/edis-hs1348-2023. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ "Vanilla - Vanilla planifolia". www.kew.org. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ a b c Schlüter, Philipp M.; Soto Arenas, Miguel A.; Harris, Stephen A. (December 2007). "Genetic Variation in Vanilla planifolia (Orchidaceae)" (PDF). Economic Botany. 61 (4): 328–336. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2007)61[328:GVIVPO]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 27092474.

- ^ a b de Oliveira, Renatha Tavares; da Silva Oliveira, Joana Paula; Macedo, Andrea Furtado (30 November 2022). "Vanilla beyond Vanilla planifolia and Vanilla × tahitensis: Taxonomy and Historical Notes, Reproductive Biology, and Metabolites". Plants. 11 (23): 3311. doi:10.3390/plants11233311. PMC 9739750. PMID 36501350.

- ^ a b Watteyn, Charlotte; Fremout, Tobias; Karremans, Adam P.; Huarcaya, Ruthmery Pillco; Azofeifa Bolaños, José B.; Reubens, Bert; Muys, Bart (March 2020). "Vanilla distribution modeling for conservation and sustainable cultivation in a joint land sparing/sharing concept". Ecosphere. 11 (3). doi:10.1002/ecs2.3056. hdl:10669/85014.

- ^ Andrews, Henry Charles (1808). The botanist's repository for new, and rare plants containing coloured figures of such plants, as have not hitherto appeared in any similar publication with all their essential characters, botanically arranged, after the sexual system of the celebrated Linnaeus in English and Latin To each description is added, a short history of the plant, as to its time of flowering, culture, native place of growth, when introduced, and by whom The whole executed by Henry Andrews. Vol. 8. London: The author. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ Ellestad, Paige; Forest, Félix; Serpe, Marcelo; Novak, Stephen J; Buerki, Sven (21 June 2021). "Harnessing large-scale biodiversity data to infer the current distribution of Vanilla planifolia (Orchidaceae)". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 196 (3): 407–422. doi:10.1093/botlinnean/boab005. Retrieved 23 March 2023.

- ^ "Vanilla Diseases and Pests, Description, Uses, Propagation". plantvillage.psu.edu.

- ^ Lubinsky, Pesach; Van Dam, Matthew; Van Dam, Alex (January 2006). ""Pollination of Vanilla and evolution in Orchidaceae"". Lindleyana. 75: 926–929. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ Eltz, Thomas; Fritzsch, Falko; Zimmermann, Yvonne; Pech, Jorge Ramirez; Ramirez, Santiago R.; Quezada-Euan, J. Javier G.; Bembe, Benjamin (2011). "Characterization of the orchid bee Euglossa viridissima (Apidae: Euglossini) and a novel cryptic sibling species, by morphological, chemical, and genetic characters". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2011 (163): 1064–1076. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00740.x.

- ^ Schlüter, Philipp M.; Arenas, Miguel A. Soto; Harris, Stephen A. (2007). "Genetic Variation in Vanilla planifolia (Orchidaceae)". Economic Botany. 61 (4): 328–336. doi:10.1663/0013-0001(2007)61[328:GVIVPO]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0013-0001. JSTOR 25568893. S2CID 27092474. Retrieved 6 March 2023.

- ^ José Javier G. Quezada-Euán, Roger O. Guerrero-Herrera, Raymundo M. González-Ramírez, David W. MacFarlane (2024) Frequency and behavior of Melipona stingless bees and orchid bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) in relation to floral characteristics of vanilla in the Yucatán region of Mexico. PLOS ONE, July 2024. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0306808

- ^ a b c Karremans, Adam P.; Bogarín, Diego; Fernández Otárola, Mauricio; Sharma, Jyotsna; Watteyn, Charlotte; Warner, Jorge; Rodríguez Herrera, Bernal; Chinchilla, Isler F.; Carman, Ernesto; Rojas Valerio, Emmanuel; Pillco Huarcaya, Ruthmery; Whitworth, Andy (January 2023). "First evidence for multimodal animal seed dispersal in orchids". Current Biology. 33 (2): 364–371.e3. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.11.041. PMID 36521493. S2CID 254705363.

- ^ Reinvestigation of vanillin contents and component ratios of vanilla extracts using high-performance liquid chromatography and gas chromatography. Scharrer A and Mosandl A, Deutsche Lebensmittel-Rundschau, 2001, volume 97, number 12, pages 449-456, INIST 14118840

- ^ Havkin-Frenkel, D., & Belanger, F. C. (2011). Handbook of Vanilla Science and Technology. Wiley-Blackwell.

- ^ "Vanilla planifolia Vanilla PFAF Plant Database". pfaf.org.

- ^ a b Favre, Félicien; Jourda, Cyril; Grisoni, Michel; Piet, Quentin; Rivallan, Ronan; Dijoux, Jean-Bernard; Hascoat, Jérémy; Lepers-Andrzejewski, Sandra; Besse, Pascale; Charron, Carine (August 2022). "A genome-wide assessment of the genetic diversity, evolution and relationships with allied species of the clonally propagated crop Vanilla planifolia Jacks. ex Andrews". Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution. 69 (6): 2125–2139. doi:10.1007/s10722-022-01362-1. Retrieved 26 March 2023.

- ^ GRIN-Global Web v 1.9.4.2: Taxonomy of Vanilla planifolia

- ^ "Grow Your Own Vanilla for Desserts and Drinks". The Spruce. Retrieved 2024-01-21.