Equals sign

| = | |

|---|---|

Equals sign | |

| In Unicode | U+003D = EQUALS SIGN (=) |

| Related | |

| See also | U+2260 ≠ NOT EQUAL TO U+2248 ≈ ALMOST EQUAL TO U+2261 ≡ IDENTICAL TO |

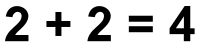

The equals sign (British English) or equal sign (American English), also known as the equality sign, is the mathematical symbol =, which is used to indicate equality in some well-defined sense.[1] In an equation, it is placed between two expressions that have the same value, or for which one studies the conditions under which they have the same value.

In Unicode and ASCII, it has the code point U+003D.[2] It was invented in 1557 by Robert Recorde.

History

[edit]The etymology of the word equal is from the Latin word æqualis,[3] as meaning 'uniform', 'identical', or 'equal', from æquus ('level', 'even', or 'just').

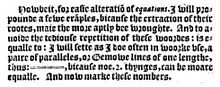

The = symbol, now universally accepted in mathematics for equality, was first recorded by Welsh mathematician Robert Recorde in The Whetstone of Witte (1557).[4] The original form of the symbol was much wider than the present form. In his book Recorde explains his design of the "Gemowe lines" (meaning twin lines, from the Latin gemellus)[5]

And to auoide the tediouſe repetition of theſe woordes : is equalle to : I will ſette as I doe often in woorke vſe, a paire of paralleles, or Gemowe lines of one lengthe, thus: =, bicauſe noe .2. thynges, can be moare equalle.

And to avoid the tedious repetition of these words: "is equal to" I will set as I do often in work use, a pair of parallels, or duplicate lines of one [the same] length, thus: =, because no 2 things can be more equal.

— Recorde, Robert (1557). The Whetstone of Witte. London: John Kyngstone. the third page of the chapter "The rule of equation, commonly called Algebers Rule."

"The symbol = was not immediately popular. The symbol || was used by some and æ (or œ), from the Latin word aequalis meaning equal, was widely used into the 1700s" (History of Mathematics, University of St Andrews).[6]

Usage in mathematics and computer programming

[edit]In mathematics, the equal sign can be used as a simple statement of fact in a specific case ("x = 2"), or to create definitions ("let x = 2"), conditional statements ("if x = 2, then ..."), or to express a universal equivalence ("(x + 1)2 = x2 + 2x + 1").

The first important computer programming language to use the equal sign was the original version of Fortran, FORTRAN I, designed in 1954 and implemented in 1957. In Fortran, = serves as an assignment operator: X = 2 sets the value of X to 2. This somewhat resembles the use of = in a mathematical definition, but with different semantics: the expression following = is evaluated first, and may refer to a previous value of X. For example, the assignment X = X + 2 increases the value of X by 2.

A rival programming-language usage was pioneered by the original version of ALGOL, which was designed in 1958 and implemented in 1960. ALGOL included a relational operator that tested for equality, allowing constructions like if x = 2 with essentially the same meaning of = as the conditional usage in mathematics. The equal sign was reserved for this usage.

Both usages have remained common in different programming languages into the early 21st century. As well as Fortran, = is used for assignment in such languages as C, Perl, Python, AWK, and their descendants. But = is used for equality and not assignment in the Pascal family, Ada, Eiffel, APL, and other languages.

A few languages, such as BASIC and PL/I, have used the equal sign to mean both assignment and equality, distinguished by context. However, in most languages where = has one of these meanings, a different character or, more often, a sequence of characters is used for the other meaning. Following ALGOL, most languages that use = for equality use := for assignment, although APL, with its special character set, uses a left-pointing arrow.

Fortran did not have an equality operator (it was only possible to compare an expression to zero, using the arithmetic IF statement) until FORTRAN IV was released in 1962, since when it has used the four characters .EQ. to test for equality. The language B introduced the use of == with this meaning, which has been copied by its descendant C and most later languages where = means assignment.

Some languages additionally feature the "spaceship operator", or three-way comparison operator, <=>, to determine whether one value is less than, equal to, or greater than another.

Several equal signs

[edit]In some programming languages, == and === are used to check equality, so 1844 == 1844 will return true.

In PHP, the triple equal sign, ===, denotes value and type equality,[7] meaning that not only do the two expressions evaluate to equal values, but they are also of the same data type. For instance, the expression 0 == false is true, but 0 === false is not, because the number 0 is an integer value whereas false is a Boolean value.

JavaScript has the same semantics for ===, referred to as "equality without type coercion". However, in JavaScript the behavior of == cannot be described by any simple consistent rules. The expression 0 == false is true, but 0 == undefined is false, even though both sides of the == act the same in Boolean context. For this reason it is sometimes recommended to avoid the == operator in JavaScript in favor of ===.[8]

In Ruby, equality under == requires both operands to be of identical type, e.g. 0 == false is false. The === operator is flexible and may be defined arbitrarily for any given type. For example, a value of type Range is a range of integers, such as 1800..1899. (1800..1899) == 1844 is false, since the types are different (Range vs. Integer); however (1800..1899) === 1844 is true, since === on Range values means "inclusion in the range".[9] Under these semantics, === is non-symmetric; e.g. 1844 === (1800..1899) is false, since it is interpreted to mean Integer#=== rather than Range#===.[10]

Other uses

[edit]Spelling

[edit]Tone letter

[edit]The equal sign is also used as a grammatical tone letter in the orthographies of Budu in the Congo-Kinshasa, in Krumen, Mwan and Dan in the Ivory Coast.[11][12] The Unicode character used for the tone letter (U+A78A ꞊ MODIFIER LETTER SHORT EQUALS SIGN)[13] is different from the mathematical symbol (U+003D).

Personal names

[edit]

A possibly unique case of the equal sign of European usage in a person's name, specifically in a double-barreled name, was by pioneer aviator Alberto Santos-Dumont, as he is also known not only to have often used a double hyphen ⹀ resembling an equal sign = between his two surnames in place of a hyphen, but also seems to have personally preferred that practice, to display equal respect for his father's French ethnicity and the Brazilian ethnicity of his mother.[14]

Instead of a double hyphen, the equal sign is sometimes used in Japanese as a separator between names. In Ojibwe, the readily available equal sign on most keyboards is commonly used as a substitute for a double hyphen.

Linguistics

[edit]In linguistic interlinear glosses, an equal sign is conventionally used to mark clitic boundaries: the equal sign is placed between the clitic and the word that the clitic is attached to.[15]

Chemistry

[edit]In chemical formulas, the two parallel lines denoting a double bond are commonly rendered using an equal sign (hence, a triple bond is commonly rendered using a triple bar).

LGBT activism

[edit]This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2018) |

In recent years, the equal sign has been used to symbolize LGBT rights. The symbol has been used since 1995 by the Human Rights Campaign, which lobbies for marriage equality, and subsequently by the United Nations Free & Equal, which promotes LGBT rights at the United Nations.[16]

Telegrams and Telex

[edit]In Morse code, the equal sign is encoded by the letters B (-...) and T (-) run together (-...-).[citation needed] The letters BT stand for Break Text, and are put between paragraphs, or groups of paragraphs in messages sent via Telex,[citation needed] a standardised tele-typewriter. The sign, used to mean Break Text, is given at the end of a telegram to separate the text of the message from the signature.[citation needed]

Related symbols

[edit]Approximately equal

[edit]Symbols used to denote items that are approximately equal include the following:[17]

- ≈ (U+2248 ≈ ALMOST EQUAL TO, LaTeX \approx)

- ≃ (U+2243 ≃ ASYMPTOTICALLY EQUAL TO, LaTeX \simeq), a combination of ≈ and =, also used to indicate asymptotic equality

- ≅ (U+2245 ≅ APPROXIMATELY EQUAL TO, LaTeX \cong), another combination of ≈ and =, which is also sometimes used to indicate isomorphism or congruence

- ∼ (U+223C ∼ TILDE OPERATOR, LaTeX \sim), which is also sometimes used to indicate proportionality or similarity, being related by an equivalence relation, or to indicate that a random variable is distributed according to a specific probability distribution (see also tilde), or alternatively between two quantities to indicate they are of the same order of magnitude.

- ∽ (U+223D ∽ REVERSED TILDE, LaTeX \backsim), which is also used to indicate proportionality

- ≐ (U+2250 ≐ APPROACHES THE LIMIT, LaTeX \doteq), which can also be used to represent the approach of a variable to a limit

- ≒ (U+2252 ≒ APPROXIMATELY EQUAL TO OR THE IMAGE OF, LaTeX \fallingdotseq), commonly used in Japan, Taiwan, and Korea.

- ≓ (U+2253 ≓ IMAGE OF OR APPROXIMATELY EQUAL TO, LaTeX \risingdotseq)

In some areas of East Asia such as Japan, "≒" is used to mean "the two terms are almost equal", but in other areas and specialized literature such as mathematics, "≃" is often used. In addition to its mathematical meaning, it is sometimes used in Japanese sentences with the intention of "almost the same".

Not equal

[edit]The symbol used to denote inequation (when items are not equal) is a slashed equal sign ≠ (U+2260). In LaTeX, this is done with the "\neq" command.

Most programming languages, limiting themselves to the 7-bit ASCII character set and typeable characters, use ~=, !=, /=, or <> to represent their Boolean inequality operator.

Identity

[edit]The triple bar symbol ≡ (U+2261, LaTeX \equiv) is often used to indicate an identity, a definition (which can also be represented by U+225D ≝ EQUAL TO BY DEFINITION or U+2254 ≔ COLON EQUALS), or a congruence relation in modular arithmetic. Also, in chemistry, the triple bar can be used to represent a triple bond between atoms.

Isomorphism

[edit]The symbol ≅ is often used to indicate isomorphic algebraic structures or congruent geometric figures.

In logic

[edit]Equality of truth values (through bi-implication or logical equivalence), may be denoted by various symbols including =, ~, and ⇔.

Other related symbols

[edit]Additional precomposed symbols with code points in Unicode for notations related to the equal sign include the following:[17]

- ≌ (U+224C ≌ ALL EQUAL TO)

- ≔ (U+2254 ≔ COLON EQUALS) (used to define a symbol or assign a variable)

- ≕ (U+2255 ≕ EQUALS COLON) (defines the symbol on the right-hand side)

- ≖ (U+2256 ≖ RING IN EQUAL TO)

- ≗ (U+2257 ≗ RING EQUAL TO)

- ≘ (U+2258 ≘ CORRESPONDS TO)

- ≙ (U+2259 ≙ ESTIMATES) (the left-hand side is an estimator for the right-hand side)

- ≚ (U+225A ≚ EQUIANGULAR TO)

- ≛ (U+225B ≛ STAR EQUALS)

- ≜ (U+225C ≜ DELTA EQUAL TO) (used to define a symbol)

- ≞ (U+225E ≞ MEASURED BY)

- ≟ (U+225F ≟ QUESTIONED EQUAL TO)

- ⩴ (U+2A74 ⩴ DOUBLE COLON EQUAL) (see also Backus–Naur form for

::=) - ⩵ (U+2A75 ⩵ TWO CONSECUTIVE EQUALS SIGNS)

- ⩶ (U+2A76 ⩶ THREE CONSECUTIVE EQUALS SIGNS)

Incorrect usage

[edit]The equal sign is sometimes used incorrectly within a mathematical argument to connect math steps in a non-standard way, rather than to show equality (especially by early mathematics students).

For example, if one were finding the sum, step by step, of the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, one might incorrectly write

- 1 + 2 = 3 + 3 = 6 + 4 = 10 + 5 = 15.

Structurally, this is shorthand for

- ([(1 + 2 = 3) + 3 = 6] + 4 = 10) + 5 = 15,

but the notation is incorrect, because each part of the equality has a different value. If interpreted strictly as it says, it would imply that

- 3 = 6 = 10 = 15 = 15.

A correct version of the argument would be

- 1 + 2 = 3, 3 + 3 = 6, 6 + 4 = 10, 10 + 5 = 15.

This difficulty results from subtly different uses of the sign in education. In early, arithmetic-focused grades, the equal sign may be operational; like the equal button on an electronic calculator, it demands the result of a calculation. Starting in algebra courses, the sign takes on a relational meaning of equality between two calculations. Confusion between the two uses of the sign sometimes persists at the university level.[18]

Encodings

[edit]- U+003D = EQUALS SIGN (=)

Related symbols

- U+2260 ≠ NOT EQUAL TO (≠, ≠)

- U+FE66 ﹦ SMALL EQUALS SIGN

- U+FF1D = FULLWIDTH EQUALS SIGN

- U+1F7F0 🟰 HEAVY EQUALS SIGN

- U+224D ≍ EQUIVALENT TO

- U+226D ≭ NOT EQUIVALENT TO

- U+2261 ≡ IDENTICAL TO

- U+2262 ≢ NOT IDENTICAL TO

- U+2263 ≣ STRICTLY EQUIVALENT TO

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. "Equal". mathworld.wolfram.com. Archived from the original on 2020-09-14. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ "C0 Controls and Basic Latin Range: 0000–007F" (PDF). Unicode Consortium. p. 0025 – 0041. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-05-26. Retrieved 2021-03-29.

- ^ "Definition of EQUAL". Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 2020-09-15. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ "The History of Equality Symbols in Math". Sciencing. Archived from the original on 2020-09-14. Retrieved 2020-08-09.

- ^ See also geminus and Gemini.

- ^ "Robert Recorde". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. Archived from the original on 29 November 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ "Comparison Operators". Php.net. Archived from the original on 19 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Crockford, Doug. "JavaScript: The Good Parts". YouTube. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ why the lucky stiff. "5.1 This One's For the Disenfranchised". why's (poignant) Guide to Ruby. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Rasmussen, Brett (30 July 2009). "Don't Call it Case Equality". pmamediagroup.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Peter G. Constable; Lorna A. Priest (31 July 2006). Proposal to Encode Additional Orthographic and Modifier Characters (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Hartell, Rhonda L., ed. (1993). The Alphabets of Africa. Dakar: UNESCO and SIL. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ "Unicode Latin Extended-D code chart" (PDF). Unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Gray, Carroll F. (November 2006). "The 1906 Santos=Dumont No. 14bis". W.W.1 Aero: The Journal of the Early Aeroplane. No. 194. p. 4.

- ^ "Conventions for interlinear morpheme-by-morpheme glosses". Archived from the original on 2019-08-04. Retrieved 2017-11-20.

- ^ "HRC Story: Our Logo." Archived 2018-07-18 at the Wayback Machine The Human Rights Campaign. HRC.org, Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Mathematical Operators" (PDF). Unicode.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ^ Capraro, Robert M.; Capraro, Mary Margaret; Yetkiner, Ebrar Z.; Corlu, Sencer M.; Ozel, Serkan; Ye, Sun; Kim, Hae Gyu (2011). "An International Perspective between Problem Types in Textbooks and Students' understanding of relational equality". Mediterranean Journal for Research in Mathematics Education. 10 (1–2): 187–213. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

References

[edit]- Cajori, Florian (1993). A History of Mathematical Notations. New York: Dover (reprint). ISBN 0-486-67766-4.

- Boyer, C. B.: A History of Mathematics, 2nd ed. rev. by Uta C. Merzbach. New York: Wiley, 1989 ISBN 0-471-09763-2 (1991 pbk ed. ISBN 0-471-54397-7)