Eurasian wryneck

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Eurasian wryneck | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Piciformes |

| Family: | Picidae |

| Genus: | Jynx |

| Species: | J. torquilla

|

| Binomial name | |

| Jynx torquilla | |

| Subspecies | |

|

See text | |

| |

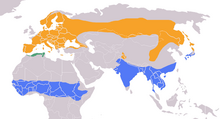

| Range map for Eurasian wryneck Summer Resident Winter | |

The Eurasian wryneck or northern wryneck (Jynx torquilla) is a species of wryneck in the woodpecker family.[2] They mainly breed in temperate regions of Europe and Asia. Most populations are migratory, wintering in tropical Africa and in southern Asia from Iran to the Indian subcontinent, but some are resident in northwestern Africa. It is a bird of open countryside, woodland and orchards.

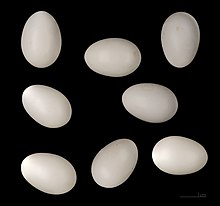

Eurasian wrynecks measure about 16.5 cm (6.5 in) in length and have bills shorter and less dagger-like than those of other woodpeckers. Their upperparts are barred and mottled in shades of pale brown with rufous and blackish bars and wider black streaks. Their underparts are cream speckled and spotted with brown. Their chief prey is ants and other insects, which they find in decaying wood or on the ground. The eggs are white as is the case with many birds that nest in holes and a clutch of seven to ten eggs is laid during May and June.

These birds get their English name from their ability to turn their heads through almost 180 degrees. When disturbed at the nest, they use this snake-like head twisting and hissing as a threat display. This odd behaviour led to their use in witchcraft, hence to put a "jinx" on someone.

Taxonomy and etymology

[edit]The Eurasian wryneck was first described by Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae in 1758. The type species came from Sweden.[3][4]

The genus name Jynx is from the Ancient Greek name for this bird, iunx. The specific torquilla is Medieval Latin derived from torquere, to twist, referring to the strange snake-head movements.[5] The bird was used as a charm to bring back an errant lover, the bird being tied to a piece of string and whirled around.[5] The English "wryneck" refers to the same twisting movement and was first recorded in 1585.[6]

The family Picidae has four subfamilies, the Picinae (woodpeckers), the Picumninae (piculets), the Jynginae (wrynecks) and the monotypic Nesoctitinae (Antillean piculet).[7] Based on morphology and behaviour, the Picumninae was considered to be the sister clade of the Picinae. This has now been confirmed by phylogenetic analysis and the Jynginae are placed basal to the Picinae, Nesoctitinae and Picumninae.[7]

Jynginae includes one genus (Jynx) and two species, the Eurasian wryneck and the red-throated wryneck (Jynx ruficollis), resident in sub-Saharan Africa.[8] There are six subspecies of Jynx torquilla: [9]

- Jynx torquilla chinensis Hesse, 1911

- Jynx torquilla himalayana Vaurie, 1959

- Jynx torquilla mauretanica Rothschild, 1909

- Jynx torquilla sarudnyi Loudon, 1912

- Jynx torquilla torquilla Linnaeus, 1758

- Jynx torquilla tschusii O. Kleinschmidt, 1907

Description

[edit]

The Eurasian wryneck grows to about 17 cm (6.7 in) in length.[4] The subspecies Jynx torquilla tschusii weighs 26 to 50 g (0.92 to 1.76 oz).[10] It is a slim, elongated-looking bird with a body shape more like a thrush than a woodpecker. The upperparts are barred and mottled in shades of pale brown with rufous and blackish bars and wider black streaks. The rump and upper tail coverts are grey with speckles and irregular bands of brown. The rounded tail is grey, speckled with brown, with faint bands of greyish-brown and a few more clearly defined bands of brownish-black. The cheeks and throat are buff barred with brown. The underparts are creamy white with brown markings shaped like arrow-heads which are reduced to spots on the lower breast and belly. The flanks are buff with similar markings and the under-tail coverts are buff with narrow brown bars. The primaries and secondaries are brown with rufous-buff markings. The beak is brown, long and slender with a broad base and sharp tip. The irises are hazel and the slender legs and feet are pale brown. The first and second toes are shorter than the others. The first and fourth toes point backwards and the second and third point forwards, a good arrangement for clinging to vertical surfaces.[4] The juvenile has a livery much similar to the adults but with a milder and less distinct coloration.[11]

The call of the Eurasian wryneck is a series of repeated harsh, shrill notes quee-quee-quee-quee lasting for several seconds and is reminiscent of the voice of the lesser spotted woodpecker. Its alarm call is a short series of staccato "tuck"s and when disturbed on the nest it hisses.[4]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The Eurasian wryneck has a palearctic distribution. The breeding range of the nominate subspecies includes all of Europe to the Urals, except the British Isles, where it was extirpated in the 20th century, and Iceland. In the north it reaches the Arctic Circle and the range includes Spain in the southwest. In the south and east it intergrades with J. t. tschusii (smaller and more reddish brown) which is found in Corsica, Italy, Dalmatia and parts of the Balkans. J. t. mauretanica (also smaller than the nominate form, light, with whitish throat and breast) is resident in Algeria and Morocco and possibly also the Balearic Islands, Sardinia and parts of Sicily. J. t. sarudnyi (considerably paler than the nominate with fainter markings) occurs in the Urals and then in a wide strip of Asia through southern Siberia, Central Asia, including the north-western Himalayas to the Pacific coast. J. t. chinensis breeds in eastern Siberia and northeastern and central China while J. t. himalayana breeds in Pakistan and the northwestern Himalayas.[12] Eurasian wrynecks also inhabit the island of Sakhalin,[13] Japan and the coastal areas of southern China.[1][14]

The Eurasian wryneck is the only European woodpecker to undertake long-distance migrations. The wintering area of European species is located south of the Sahara, in a wide strip across Africa extending from Senegal, Gambia and Sierra Leone in the west to Ethiopia in the east. Its southern limit extends to the Democratic Republic of Congo and Cameroon. The populations from West Asia use the same wintering areas. The Central and East Asian breeding birds winter in the Indian subcontinent or southern East Asia including southern Japan.[4]

During the summer the bird is found in open countryside, parkland, gardens, orchards, heaths and hedgerows, especially where there are some old trees. It may also inhabit deciduous woodland and in Scandinavia it also occurs in coniferous forests.[4]

Behaviour

[edit]

The Eurasian wryneck sometimes forms small groups during migration and in its winter quarters but in the summer is usually found in pairs. It characteristically holds its head high with its beak pointing slightly upwards. A mutual display that occurs at any time of year involves two birds perched facing each other with their heads far back and beaks wide open, bobbing their heads up and down. Sometimes the head is allowed to slump sideways and hang limply. On other occasions, when excited, the head is shaken and twisted about violently. When disturbed on the nest or held in the hand, the neck contorts and twists in all directions. The bird sometimes feigns death and hangs limply with eyes closed.[4]

On returning to the breeding area after migration, the birds set up territories. On farmland in Switzerland it has been found that old pear orchards with large numbers of ant nests are preferentially selected over other habitats. Areas used for vegetable cultivation provided useful habitat when they include areas of bare ground on which the birds can forage.[15] Territories are not chosen at random as arriving birds favoured certain areas over others with the same territories being colonised first year after year. The presence of other Eurasian wrynecks in the vicinity is also a positive influence. Orchards in general, and older ones in particular, provide favoured territories, probably because the dense foliage is more likely to support high numbers of aphids and the ground beneath has scant vegetation cover, both of which factors increase the availability of ants, the birds' main prey. Despite some territories being consistently chosen over others, reproductive success in these territories was no higher than in others.[16] Limiting factors for such crevice-nesting species as Eurasian wrynecks are both the availability of nesting sites and the number of ants and their ease of discovery. Modern farming practices such as the removal of hedges, forest patches and isolated trees and the increasing use of fertilisers and pesticides are disadvantageous to such birds.[17]

The diet of the Eurasian wryneck consists chiefly of ants but beetles and their larvae, moths, spiders and woodlice are also eaten. Although much time is spent in the upper branches of trees, the bird sometimes perches in low bushes and mostly forages on the ground, moving around with short hops with its tail held in a raised position. It can cling to tree trunks, often moving obliquely, and sometimes pressing its tail against the surface as a prop. It does not make holes in bark with its beak but picks up prey with a rapid extension and retraction of its tongue and it sometimes catches insects while on the wing. Its flight is rather slow and undulating.[4]

Breeding

[edit]

The nesting site is variable and may be in a pre-existing hole in a tree trunk, a crevice in a wall, a hole in a bank, a sand martin's burrow or a nesting box.[4] In its search for a safe, protected site out of reach of predators, it sometimes evicts a previous occupant, its eggs and nestlings.[18] It uses no nesting material, and a clutch of normally seven to ten eggs is laid (occasionally five, six, eleven or twelve). The eggs average 20.8 by 15.4 millimetres (0.82 in × 0.61 in) and weigh about 0.2 g (0.007 oz). They are a dull white colour and partially opaque. Both sexes are involved in incubation, which takes twelve days, but the female plays the greater part. Both parents feed the chicks for about twenty days before they fledge. There is usually a single brood.[4]

Status

[edit]The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the Eurasian wryneck as being of "least concern" in its Red List of Threatened Species. This is because it has a world population estimated at up to fifteen million individual birds and a very wide geographical range. The population may be decreasing to a certain extent but not at such a rate as to make the bird reach the threshold for a more threatened category.[1] In continental Europe, the largest populations are in Spain, Italy, Germany, Poland, Romania, Hungary, Belarus and Ukraine, and only in Romania is the population trend believed to be upward. In Russia, where there are believed to be 300,000 to 800,000 individuals, the population trend is unknown.[19] In the United Kingdom the numbers of bird are on the decrease and it is protected under Schedule 1 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 and is listed on Appendix II of the Bern Convention. It is protected as a migratory species under the Birds Directive in the European Union.[20] In Switzerland, the population has also been decreasing, but the species has reacted positively to conservation measures such as the addition of nestboxes in suitable habitats.[21]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c BirdLife International (2017). "Jynx torquilla". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22680683A111819000. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-1.RLTS.T22680683A111819000.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Winkler, H., Christie, D. A. & Kirwan, G. M. (2019). "Eurasian Wryneck (Jynx torquilla)". In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- ^ Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Witherby, H. F., ed. (1943). Handbook of British Birds, Volume 2: Warblers to Owls. H. F. and G. Witherby Ltd. pp. 292–296.

- ^ a b Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 212, 388. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ "Wryneck". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- ^ a b Benz, Brett W.; Robbins, Mark B.; Peterson, A. Townsend (2006). "Evolutionary history of woodpeckers and allies (Aves: Picidae): Placing key taxa on the phylogenetic tree". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 40 (2): 389–399. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2006.02.021. PMID 16635580.

- ^ BirdLife International (2016). "Jynx ruficollis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22680689A92872725. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22680689A92872725.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Lepage, Denis. "Eurasian Wryneck (Jynx torquilla) Linnaeus, 1758". Avibase. Retrieved 2013-08-06.

- ^ CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- ^ "Jynx torquilla". July 2015.

- ^ "Eurasian Wryneck - Jynx torquilla: Subspecies". Cuba.observado.org. Retrieved 2013-10-01.

- ^ "Eurasian Wryneck (Jynx torquilla)". Sakhalin Check List. iNaturalist.org. Retrieved 2013-10-15.

- ^ Butchart, S.; Ekstrom, J. "Eurasian Wryneck Jynx torquilla". BirdLife International. Archived from the original on 2016-10-21. Retrieved 2013-08-06.

- ^ Mermod, M.; Reichlin, T. S.; Arlettaz, R.; Schaub, M. (2009). "The importance of ant-rich habitats for the persistence of the Wryneck (Jynx torquilla) on farmland". Ibis. 151 (4): 731–742. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.2009.00956.x.

- ^ Mermod, Murielle; Arlettaz, R.; Schaub, P. D. M. (2008). Key ecological features for the persistence of an endangered migratory woodpecker of farmland, the wryneck (Jynx torquilla) (PDF) (Thesis).

- ^ Coudrain, Valérie; Arlettaz, Raphaël; Schaub, Michael (2010). "Food or nesting place? Identifying factors limiting Wryneck populations" (PDF). Journal of Ornithology. 161 (4): 867–880. doi:10.1007/s10336-010-0525-9. S2CID 2065752.

- ^ Alerstam, Thomas; Högstedt, Göran (1981). "Evolution of hole-nesting in birds". Ornis Scandinavica. 12 (3): 188–193. doi:10.2307/3676076. JSTOR 3676076.

- ^ "Jynx torquilla: Eurasian wryneck" (PDF). Birds in Europe: Wrynecks, Woodpeckers. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

- ^ "Wryneck Jynx torquilla". ARKive. Wildscreen. Archived from the original on 2008-12-05. Retrieved 2013-08-06.

- ^ "vogelwarte.ch - Conservation du torcol fourmilier". www.vogelwarte.ch. Retrieved 2017-06-02.

External links

[edit] Data related to Jynx torquilla at Wikispecies

Data related to Jynx torquilla at Wikispecies Media related to Jynx torquilla at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Jynx torquilla at Wikimedia Commons