Normandy landings: Difference between revisions

grammar |

AnkaraCity (talk | contribs) Germany didn't invade the USA, the USA victimised Germany (and the residents of Normandy) by this action |

||

| Line 269: | Line 269: | ||

[[Category:Battles involving the United Kingdom|Neptune, Operation]] |

[[Category:Battles involving the United Kingdom|Neptune, Operation]] |

||

[[Category:Battles involving the United States|Neptune, Operation]] |

[[Category:Battles involving the United States|Neptune, Operation]] |

||

[[Category:Crime of aggression]] |

|||

{{Link FA|de}} |

{{Link FA|de}} |

||

Revision as of 13:34, 23 August 2008

| Operation Neptune | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Operation Overlord | |||||||||

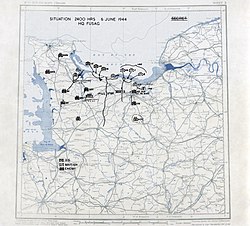

Landing operations off the coast of Normandy, June 1944 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Dwight D. Eisenhower Bernard Law Montgomery Omar Bradley Trafford Leigh-Mallory Arthur Tedder Miles Dempsey Bertram Ramsay |

Erwin Rommel Gerd von Rundstedt Friedrich Dollmann Adolf Hitler | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 1,000,000 by July 4 | 380,000 by July 23 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

United States- 1,465 dead 5,138 missing, wounded, or captured. United Kingdom- 2,700 dead, wounded, or captured. Canada, 500 dead, 621 wounded or captured. The total number of allied casualties was 10,264. | Between 4,000 and 9,000 dead, wounded, or captured | ||||||||

The Normandy Landings were the first operations of the Allied Powers' invasion of Normandy, also known as Operation Neptune and Operation Overlord, during World War II. D-Day for the operation, postponed 24 hours, became June 6, 1944, H-Hour was 6:30 am. The assault was conducted in two phases: an air assault landing of American and British airborne divisions shortly after midnight, and an amphibious landing of Allied infantry and armoured divisions on the coast of France commencing at 06:30 British Double Summer Time. It required the transport of soldiers and materiel from England and Wales by troop carrying aeroplanes and ships, the assault landings, air support, naval interdiction of the English Channel and naval fire-support. There were also subsidiary operations to distract the Kriegsmarine and prevent its interference in the landing areas.[1]

The operation was the largest single-day invasion of all time, with over 130,000 troops landed on June 6 1944. 195,700 Allied naval and merchant navy personnel were involved.[2] The landings took place along a stretch of the Normandy coast divided into five sections: Gold, Juno, Omaha, Sword and Utah.

Operations

The Allied invasion was detailed in several overlapping operational plans according to the D-Day museum:

- "The armed forces use codenames to refer to the planning and execution of specific military operations. Operation Overlord was the codename for the Allied invasion of northwest Europe. The assault phase of Operation Overlord was known as Operation Neptune. (...) Operation Neptune began on D-Day (6 June 1944) and ended on 30 June 1944. By this time, the Allies had established a firm foothold in Normandy. Operation Overlord also began on D-Day, and continued until Allied forces crossed the River Seine on 19th August."[3]

Weather

A full moon was required for light, for the aircraft pilots and for the spring tide, effectively limiting the window of opportunity for mounting the invasion to only a few days in each month. Allied Expeditionary Force Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower had tentatively selected June 5 as the date for the assault. Most of May had fine weather, but this deteriorated in early June. On June 4, conditions were clearly unsuitable for a landing; wind and high seas would make it impossible to launch landing craft, and low clouds would prevent aircraft finding their targets. The Allied troop convoys already at sea were forced to take shelter in bays and inlets on the south coast of Britain for the night.

It seemed possible that everything would have to be canceled and the troops returned to their camps (a vast undertaking because the enormous movement of follow-up formations was already proceeding). The next full moon period would be nearly a month away. At a vital meeting on June 5, Eisenhower's chief meteorologist (Group Captain J.M. Stagg) forecast a brief improvement for June 6. General Bernard Montgomery and Eisenhower's Chief of Staff General Walter Bedell Smith wished to proceed with the invasion. Leigh Mallory was doubtful, but Admiral Bertram Ramsay believed that conditions would be marginally favorable. On the strength of Stagg's forecast, Eisenhower ordered the invasion to proceed.

The Germans meanwhile took comfort from the existing poor conditions, which were worse over Northern France than over the Channel itself, and believed no invasion would be possible for several days. Some troops stood down, and many senior officers were away for the weekend. General Erwin Rommel, for example, took a few days' leave with his wife and family, while dozens of division, regimental, and battalion commanders were away from their posts at war games.

Allied Order of Battle

The order of battle for the landings was approximately as follows, east to west:

British sector (Second Army)

- 6th Airborne Division was delivered by parachute and glider to the east of the River Orne to protect the left flank. The division contained 7,900 men, including one Canadian battalion.[4][page needed]

- 1st Special Service Brigade comprising No.3, No.4, No.6 and No.45 (RM) Commandos landed at Ouistreham in Queen Red sector (leftmost). No.4 Commando were augmented by 1 and 8 Troop (both French) of No.10 (Inter Allied) Commando.

- I Corps (United Kingdom), 3rd Infantry Division and the 27th Armoured Brigade on Sword Beach, from Ouistreham to Lion-sur-Mer.

- No.41 (RM) Commando (part of 4th Special Service Brigade) landed on the far West of Sword Beach.[5]

- 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade and No.48 (RM) Commando on Juno Beach, from Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer to Courseulles-sur-Mer.[4]

- No.46(RM) Commando (part of 4th Special Service Brigade) at Juno to scale the cliffs on the left side of the Orne River estuary and destroy a battery. (Battery fire proved negligible so No.46 were kept off-shore as a floating reserve and landed on D+1).

- XXX Corps, 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division and 8th Armoured Brigade, consisting of 25,000 men landing on Gold Beach,[6] from Courseulles to Arromanches.

- No.47(RM) Commando (part of 4th Special Service Brigade) on the West flank of Gold beach.

- 79th Armoured Division operated specialist armour ("Hobart's Funnies") for mine-clearing, recovery and assault tasks. These were distributed around the Anglo-Canadian beaches.

Overall, the British contingent would consist of 83,115 troops (61,715 of them British).[4] In addition to the British and Canadian combat units, two troops of No. 10 Commando were employed, manned by Frenchmen, and eight Australian officers were attached to the British forces as observers.[7] The nominally British air and naval support units included a large number of crew from Allied nations, including several RAF squadrons manned almost exclusively by foreign flight crew.

U.S. Sector (First Army)

- V Corps, 1st Infantry Division and 29th Infantry Division making up 34,250 troops for Omaha Beach, from Sainte-Honorine-des-Pertes to Vierville-sur-Mer.[4][8]

- 2nd and 5th Ranger Battalions at Pointe du Hoc (The 5th diverted to Omaha).[8]

- VII Corps, 4th Infantry Division and the 359th RCT of the 90th Infantry Division comprising of 23,250 men landing on Utah Beach, around Pouppeville and La Madeleine.[8]

- 101st Airborne Division by parachute around Vierville to support Utah Beach landings.[8]

- 82nd Airborne Division by parachute around Sainte-Mère-Église, protecting the right flank. They had originally been tasked with dropping further west, in the middle part of the Cotentin, allowing the sea-landing forces to their east easier access across the peninsula, and preventing the Germans from reinforcing the north part of the peninsula. The plans were later changed to move them much closer to the beachhead, as at the last minute the German 91st Air Landing Division was determined to be in the area.[9][8]

In total, the Americans contributed 73,000 men (15,500 were airborne).[4]

German Order of Battle

The number of military forces at the disposal of Nazi Germany reached its peak during 1944. By D-Day 157 German divisions were stationed in the Soviet Union, 6 in Finland, 12 in Norway, 6 in Denmark, 9 in Germany, 21 in the Balkans, 26 in Italy and 59 in France, Belgium and the Netherlands.[10] However, these statistics are somewhat misleading since a significant number of the divisions in the east were depleted; German records indicate that the average personnel complement was at about 50% in the spring of 1944.[11]

Atlantic Wall

Standing in the way of the Allies was the English Channel, a crossing which had eluded the Spanish Armada and Napoleon Bonaparte's Navy. Compounding the invasion efforts was the extensive Atlantic Wall, ordered by Hitler in his Directive 51. Believing that any forthcoming landings would be timed for high tide (this caused the landings to be timed for low tide), Rommel had the entire wall fortified with tank top turrets and extensive barbed wire, and laid a million mines to deter landing craft. The sector which was attacked was guarded by four divisions.

Divisional Areas

- 716th Infantry Division (Static) defended the Eastern end of the landing zones, including most of the British and Canadian beaches. This division, as well as the 709th, included Germans who were not considered fit for active duty on the Eastern Front, usually for medical reasons, and soldiers of various other nationalities (from conquered countries, often drafted by force) and former Soviet prisoners-of-war who had agreed to fight for the Germans rather than endure the harsh conditions of German POW camps (among them so called hiwis).

- 352nd Infantry Division defended the area between approximately Bayeux and Carentan, including Omaha beach. Unlike the other divisions this one was well-trained and contained many combat veterans. The division had been formed in November 1943 with the help of cadres from the disbanded 321st Division, which had been destroyed in the Soviet Union that same year. The 352nd had many troops who had seen action on the eastern front and on the 6th, had been carrying out anti-invasion exercises.

- 91st Air Landing Division (Luftlande – air transported) (Generalmajor Wilhelm Falley), comprising the 1057th Infantry Regiment and 1058th Infantry Regiment. This was a regular infantry division, trained, and equipped to be transported by air (i.e. transportable artillery, few heavy support weapons) located in the interior of the Cotentin Peninsula, including the drop zones of the American parachute landings. The attached 6th Parachute Regiment (Oberstleutnant Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte) had been rebuilt as a part of the 2nd Parachute Division stationed in Brittany.

- 709th Infantry Division (Static) (Generalleutnant Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben), comprising the 729th Infantry Regiment, 739th Infantry Regiment (both with four battalions, but the 729th 4th and the 739th 1st and 4th being Ost, these two regiments had no regimental support companies either), and 919th Infantry Regiment. This coastal defense division protected the eastern, and northern (including Cherbourg) coast of the Cotentin Peninsula, including the Utah beach landing zone. Like the 716th, this division comprised a number of "Ost" units who were provided with German leadership to manage them.

Adjacent Divisional Areas

Other divisions occupied the areas around the landing zones, including:

- 243rd Infantry Division (Static) (Generalleutnant Heinz Hellmich), comprising the 920th Infantry Regiment (two battalions), 921st Infantry Regiment, and 922nd Infantry Regiment. This coastal defense division protected the western coast of the Cotentin Peninsula.

- 711th Infantry Division (Static), comprising the 731th Infantry Regiment, and 744th Infantry Regiment. This division defended the western part of the Pays de Caux.

- 30th Mobile Brigade (Oberstleutnant Freiherr von und zu Aufsess), comprising three bicycle battalions.

Armoured reserves

Rommel's defensive measures were also frustrated by a dispute over armoured doctrine. In addition to his two army groups, von Rundstedt also commanded the headquarters of Panzer Group West under General Leo Geyr von Schweppenburg (usually referred to as von Geyr). This formation was nominally an administrative HQ for von Rundstedt's armoured and mobile formations, but it was later to be renamed Fifth Panzer Army and brought into the line in Normandy. Von Geyr and Rommel disagreed over the deployment and use of the vital Panzer divisions.

Rommel recognised that the Allies would possess air superiority and would be able to harass his movements from the air. He therefore proposed that the armoured formations be deployed close to the invasion beaches. In his words, it was better to have one Panzer division facing the invaders on the first day, than three Panzer divisions three days later when the Allies would already have established a firm beachhead. Von Geyr argued for the standard doctrine that the Panzer formations should be concentrated in a central position around Paris and Rouen, and deployed en masse against the main Allied beachhead when this had been identified.

The argument was eventually brought before Hitler for arbitration. He characteristically imposed an unworkable compromise solution. Only three Panzer divisions were given to Rommel, too few to cover all the threatened sectors. The remainder, nominally under Von Geyr's control, were actually designated as being in "OKW Reserve". Only three of these were deployed close enough to intervene immediately against any invasion of Northern France, the other four were dispersed in southern France and the Netherlands. Hitler reserved to himself the authority to move the divisions in OKW Reserve, or commit them to action. On June 6, many Panzer division commanders were unable to move because Hitler had not given the necessary authorisation, and his staff refused to wake him upon news of the invasion.

- The 21st Panzer Division (Generalmajor Edgar Feuchtinger) was deployed near Caen as a mobile striking force as part of the Army Group B reserve. However, Rommel placed it so close to the coastal defenses that, under standing orders in case of invasion, several of its infantry and anti-aircraft units would come under the orders of the fortress divisions on the coast, reducing the effective strength of the division.

The other mechanized divisions capable of intervening in Normandy were retained under the direct control of the German Armed Forces HQ (OKW) and were initially denied to Rommel

Coordination with the French Resistance

The various factions and circuits of the French Resistance were included in the plan for Overlord. Through a London-based headquarters which supposedly embraced all resistance groups, Etat-major des Forces Françaises de l'Interieur (EMFFI), the British Special Operations Executive orchestrated a massive campaign of sabotage tasking the various Groups with attacking railway lines, ambushing roads, or destroying telephone exchanges or electrical substations. The resistance was alerted to carry out these tasks by means of the messages personnels, transmitted by the BBC in its French service from London. Several hundred of these were regularly transmitted, masking the few of them that were really significant.

Among the stream of apparently meaningless messages broadcast by the BBC at 21:00 CET on June 5, were coded instructions such as Les carottes sont cuites ("The carrots are cooked") and Les dés sont jetés ("The dice have been thrown").[12]

One famous pair of these messages is often mistakenly stated to be a general call to arms by the Resistance. A few days before D-Day, the (slightly misquoted) first line of Verlaine's poem, Chanson d'Automne, was transmitted. "Les sanglots longs des violons de l'automne"[13][14] (Long sobs of autumn violins) alerted the resistance of the "Ventriloquist" network in the Orléans region to attack rail targets within the next few days. The second line, "Bercent mon coeur d'une langueur monotone" ("soothes my heart with a monotonous languor"), transmitted late on June 5, meant that the attack was to be mounted immediately.

Josef Götz, the head of the signals section of the German intelligence service (the SD) in Paris, had discovered the meaning of the second line of Verlaine's poem, and no fewer than fourteen other executive orders they heard late on June 5. His section rightly interpreted them to mean that invasion was imminent or underway, and they alerted their superiors and all Army commanders in France. However, they had issued a similar warning a month before, when the Allies had begun invasion preparations and alerted the Resistance, but then stood down because of a forecast of bad weather. The SD having given this false alarm, their genuine alarm was ignored or treated as merely routine. Fifteenth Army HQ passed the information on to its units; Seventh Army ignored it.[14]

In addition to the tasks given to the Resistance as part of the invasion effort, the Special Operations Executive planned to reinforce the Resistance with three-man liaison parties, under Operation Jedburgh. The Jedburgh parties would coordinate and arrange supply drops to the Maquis groups in the German rear areas. Also operating far behind German lines and frequently working closely with the Resistance, although not under SOE, were larger parties from the British, French and Belgian units of the Special Air Service brigade.

Naval activity

The Invasion Fleet was drawn from 8 different navies, comprising 6,939 vessels: 1,213 warships, 4,126 transport vessels (landing ships and landing craft), and 736 ancillary craft and 864 merchant vessels.[4]

The overall commander of the Allied Naval Expeditionary Force, providing close protection and bombardment at the beaches, was Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay who had been responsible for the planning of the invasion of North Africa in 1942 and one of the two fleets carrying troops for the invasion of Sicily in the following year. The Allied Naval Expeditionary Force was divided into two Naval Task Forces: Western (Rear-Admiral Alan G Kirk) and Eastern (Rear-Admiral Sir Philip Vian – another veteran of the Italian landings).

The warships provided cover for the transports against the enemy whether in the form of surface warships, submarines or as an aerial attack and gave support to the landings through shore bombardment. These ships included the Allied Task Force "O". A small part of the naval operation was Operation Gambit, when British midget submarines supplied navigation beacons to guide landing craft.

Participating navies

The primary ground-force participants in the landings that began Operation Neptune were nine divisions drawn from the American, British and Canadian armies. During subsequent weeks more units were landed as reinforcements.

Naval screen

An important part of Neptune was the isolation of the invasion routes and beaches from any intervention by the German Navy – the Kriegsmarine. The responsibility for this was assigned to the Royal Navy's Home Fleet. There were two principal perceived German naval threats. The first was surface attack by German capital ships from anchorages in Scandinavia and the Baltic Sea. This did not materialise since, by mid-1944, the battleships were damaged, the cruisers were used for training and the Kriegsmarine's fuel allocation had been cut by a third. The inactivity may also have resulted from Hitler's disillusion with the Kriegsmarine. In any case, the Royal Navy had strong forces available to repel any attempts, and the Kiel Canal area was mined (Operation Bravado) as a precaution.

The second perceived major threat was that of U-boats transferred from the Atlantic. Air surveillance from three escort carriers and RAF Coastal Command maintained a cordon well west of Land's End. Few U-boats were spotted, and most of the escort groups were moved nearer to the landings.

Further efforts were made to seal the Western Approaches against German naval forces from Brittany and the Bay of Biscay. Minefields were laid (Operation Maple) to force enemy ships away from air protection where they could be attacked by Allied destroyer flotillas. Again, enemy activity was minor, but on 4 July four German destroyers were either sunk or forced back to Brest.

The Straits of Dover were closed by minefields, naval and air patrols, radar, and effective bombing raids on enemy ports. Local German naval forces were small but could be reinforced from the Baltic. Their efforts, however, were concentrated on protecting the Pas de Calais against expected landings there, and no attempt was made to force the blockade.

The screening operation destroyed few German ships, but the objective was achieved. There were no U-boat attacks against Allied shipping and few attempts by surface ships.

Bombardment

Warships provided supporting fire for the land forces. During Neptune, it was given a high importance, using ships from battleships to destroyers and landing craft. For example, the Canadians at Juno beach had fire support many times greater than they had had for the Dieppe Raid in 1942. The old battleships HMS Ramillies and Warspite and the monitor HMS Roberts were used to suppress shore batteries east of the Orne; cruisers targeted shore batteries at Ver-sur-Mer and Moulineaux; eleven destroyers for local fire support. In addition, there were modified landing-craft: eight "Landing Craft Gun", each with two 4.7-inch guns; four "Landing Craft Support" with automatic cannon; eight Landing Craft Tank (Rocket), each with a single salvo of 1,100 5-inch rockets; eight Landing Craft Assault (Hedgerow), each with twenty-four bombs intended to detonate beach mines prematurely. Twenty-four Landing Craft Tank carried Priest self-propelled howitzers which also fired while they were on the run-in to the beach. Similar arrangements existed at other beaches.

Fire support went beyond the suppression of shore defences overlooking landing beaches and was also used to break up enemy concentrations as the troops moved inland. This was particularly noted in German reports: Field-Marshall Gerd von Rundstedt reported that

- ... The enemy had deployed very strong Naval forces off the shores of the bridgehead. These can be used as quickly mobile, constantly available artillery, at points where they are necessary as defence against our attacks or as support for enemy attacks. During the day their fire is skillfully directed by . . . plane observers, and by advanced ground fire spotters. Because of the high rapid-fire capacity of Naval guns they play an important part in the battle within their range. The movement of tanks by day, in open country, within the range of these naval guns is hardly possible.

Just prior to the invasion, General Eisenhower transmitted a now-historic message to all members of the Allied Expeditionary Force. It read, in part, "You are about to embark upon the great crusade, toward which we have striven these many months." [1] In his pocket was an unused statement to be read in case the invasion failed.[15]

The landings

Airborne operations

The success of the amphibious landings depended on the establishment of a secure lodgment from which to expand the beachhead to allow the build up of a well-supplied force capable of breaking out. The amphibious forces were especially vulnerable to strong enemy counterattacks before the build up of sufficient forces in the beachhead could be accomplished. To slow or eliminate the enemy's ability to organize and launch counterattacks during this critical period, airborne operations were used to seize key objectives, such as bridges, road crossings, and terrain features, particularly on the eastern and western flanks of the landing areas. The airborne landings some distance behind the beaches were also intended to ease the egress of the amphibious forces off the beaches, and in some cases to neutralize German coastal defence batteries and more quickly expand the area of the beachhead. The U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were assigned to objectives west of Utah Beach. The British 6th Airborne Division was assigned to similar objectives on the eastern flank. 500 Free French paratroopers from the British Special Air Service Brigade (S.A.S.) were assigned to objectives in Brittany from June 6 to August.

British airborne landings

East of the landing area, the open, flat, floodplain between the Orne and Dives Rivers was ideal for counterattacks by German armour. However, the landing area and floodplain were separated by the Orne River, which flowed northeast from Caen into the bay of the Seine. The only crossing of the Orne River north of Caen was 7 kilometres (4.5 mi) from the coast, near Bénouville and Ranville. For the Germans, the crossing provided the only route for a flanking attack on the beaches from the east. For the Allies, the crossing also was vital for any attack on Caen from the east.

The tactical objectives of the British 6th Airborne Division were (a) to capture intact the bridges of the Bénouville-Ranville crossing, (b) to defend the crossing against the inevitable armoured counter-attacks, (c) to destroy German artillery at the Merville battery, which threatened Sword Beach, and (d) to destroy five bridges over the Dives River to further restrict movement of ground forces from the east.

Airborne troops, mostly paratroopers of the 3rd and 5th Parachute Brigades, including the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, began landing after midnight, June 6 and immediately encountered elements of the German 716th Infantry Division. At dawn, the Battle Group von Luck of the 21st Panzer Division counterattacked from the south on both sides of the Orne River. By this time the paratroopers had established a defensive perimeter surrounding the bridgehead. Casualties were heavy on both sides, but the airborne troops held. Shortly after noon, they were reinforced by commandos of the 1st Special Service Brigade. By the end of D-Day, 6th Airborne had accomplished each of its objectives. For several days, both British and German forces took heavy casualties as they struggled for positions around the Orne bridgehead. For example, the German 346th Infantry Division broke through the eastern edge of the defensive line on June 10. Finally, British paratroopers overwhelmed entrenched panzergrenadiers in the Battle of Bréville on June 12. The Germans did not seriously threaten the bridgehead again. 6th Airborne remained on the line until it was evacuated in early September.

American airborne landings

The U.S. 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, numbering 13,000 paratroopers and delivered by 12 troop carrier groups of the IX Troop Carrier Command, were less fortunate in quickly completing their main objectives. To achieve surprise, the drops were routed to approach Normandy from the west. Numerous factors affected their performance, but the primary one was the decision to make a massive parachute drop at night (a tactic not used again for the rest of the war). As a result, 45% of units were widely scattered and unable to rally. Efforts of the early wave of pathfinder teams to mark the landing zones were largely ineffective, and the Rebecca/Eureka transponding radar beacons used to guide in the waves of C-47 Skytrains to the drop zones were a flawed system.

Three regiments of 101st Airborne paratroopers were dropped first, between 00:48 and 01:40, followed by the 82nd Airborne's drops between 01:51 and 02:42. Each operation involved approximately 400 C-47 aircraft. Two pre-dawn glider landings brought in anti-tank guns and support troops for each division. On the evening of D-Day two additional glider landings brought in two battalions of artillery and 24 howitzers to the 82nd Airborne. Additional glider operations on June 7 delivered the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment to the 82nd Airborne, and two large supply parachute drops that date were ineffective.

After 24 hours, only 2,500 troops of the 101st and 2,000 of the 82nd were under the control of their divisions, approximating a third of the force dropped. The dispersal of the American airborne troops, however, had the effect of confusing the Germans and fragmenting their response. In addition, the Germans' defensive flooding, in the early stages, also helped to protect the Americans' southern flank.

Paratroopers continued to roam and fight behind enemy lines for days. Many consolidated into small groups, rallied with NCOs or junior officers, and usually were a hodgepodge of men from different companies, battalions, regiments, or even divisions. The 82nd occupied the town of Sainte-Mère-Église early in the morning of June 6, giving it the claim of the first town liberated in the invasion.

Amphibious landings

Sword Beach

The assault on Sword Beach began at about 03:00 with an aerial bombardment of the German coastal defences and artillery sites. The naval bombardment began a few hours later. At 07:30, the first units reached the beach. These were the DD tanks of 13th/18th Hussars followed closely by the infantry of 8th Brigade.

On Sword Beach, the regular British infantry came ashore with light casualties. They had advanced about 8 kilometres (5 mi) by the end of the day but failed to make some of the deliberately ambitious targets set by Montgomery. In particular, Caen, a major objective, was still in German hands by the end of D-Day, and would remain so until the Battle for Caen, August 8.

1st Special Service Brigade, under the command of Brigadier The Lord Lovat DSO, MC, went ashore in the second wave led by No.4 Commando with the two French Troops first, as agreed amongst themselves. The 1st Special Service Brigade's landing is famous for having been led by Piper Bill Millin. The British and French of No.4 Commando had separate targets in Ouistreham: the French a blockhouse and the Casino, and the two German batteries which overlooked the beach. The blockhouse proved too strong for the Commandos' PIAT (Projector Infantry Anti Tank) weapons, but the Casino was taken with the aid of a Centaur tank. The British Commandos achieved both battery objectives only to find the gun mounts empty and the guns removed. Leaving the mopping-up procedure to the infantry, the Commandos withdrew from Ouistreham to join the other units of their brigade (Nos.3, 6 and 45), moving inland to join-up with the 6th Airborne Division.

Juno Beach

The Canadian forces that landed on Juno Beach faced 11 heavy batteries of 155 mm guns and 9 medium batteries of 75 mm guns, as well as machine-gun nests, pillboxes, other concrete fortifications, and a seawall twice the height of the one at Omaha Beach. The first wave suffered 50% casualties, the second highest of the five D-Day beachheads. The use of armour was successful at Juno, in some instances actually landing ahead of the infantry as intended and helping clear a path inland.[16]

Despite the obstacles, the Canadians were off the beach within hours and beginning their advance inland. The 6th Canadian Armoured Regiment (1st Hussars) and The Queen's Own Rifles of Canada achieved their June 6 objectives, when they crossed the Caen–Bayeux highway over 15 kilometres (9 mi) inland.[17] The Canadians were the only units to reach their D-Day objectives, although most units fell back a few kilometres to stronger defensive positions. In particular, the Douvres Radar Station was still in German hands, and no link had been established with Sword Beach.

By the end of D-Day, 15,000 Canadians had been successfully landed, and the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division had penetrated further into France than any other Allied force, despite having faced strong resistance at the water's edge and later counterattacks on the beachhead by elements of the German 21st and 12th SS Hitlerjugend Panzer divisions on June 7 and June 8.

Gold Beach

At Gold Beach, the casualties were also quite heavy, partly because the swimming Sherman DD tanks were delayed, and the Germans had strongly fortified a village on the beach. However, the 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division overcame these difficulties and advanced almost to the outskirts of Bayeux by the end of the day. With the exception of the Canadians at Juno Beach, no division came closer to its objectives than the 50th.

No.47 (RM) Commando was the last British Commando unit to land and came ashore on Gold east of Le Hamel. Their task was to proceed inland then turn right (west) and make a 16-kilometre (10 mi) march through enemy territory to attack the coastal harbour of Port en Bessin from the rear. This small port, on the British extreme right, was well sheltered in the chalk cliffs and significant in that it was to be a prime early harbour for supplies to be brought in including fuel by underwater pipe from tankers moored offshore.

Omaha Beach

Elements of the 1st Infantry Division and 29th Infantry Division faced the veteran German 352nd Infantry Division, one of the best trained on the beaches. Allied intelligence failed to realize that the relatively low-quality 716th Infantry Division (static) had been replaced by the 352nd the previous March. Omaha was also the most heavily fortified beach, with high bluffs defended by funneled mortars, machine guns, and artillery, and the pre-landing aerial and naval bombardment of the bunkers proved to be ineffective. Difficulties in navigation caused the majority of landings to drift eastwards, missing their assigned sectors, and the initial assault waves of tanks, infantry and engineers took heavy casualties. Of the 16 tanks that landed upon the shores of Omaha Beach only 2 survived the landing. The official record stated that "within 10 minutes of the ramps being lowered, [the leading] company had become inert, leaderless and almost incapable of action. Every officer and sergeant had been killed or wounded […] It had become a struggle for survival and rescue". Only a few gaps were blown in the beach obstacles, resulting in problems for subsequent landings. The heavily defended draws, the only vehicular routes off the beach, could not be taken and two hours after the first assault the beach was closed for all but infantry landings. Commanders (including General Omar Bradley) considered abandoning the beachhead, but small units of infantry, often forming ad hoc groups, supported by naval artillery and the surviving tanks, eventually infiltrated the coastal defenses by scaling the bluffs between strongpoints. Further infantry landings were able to exploit the initial penetrations and by the end of the day two isolated footholds had been established. American casualties at Omaha on D-Day numbered around 3,000 out of 34,000 men, most in the first few hours, while the defending forces suffered 1,200 killed, wounded or missing. The tenuous beachhead was expanded over the following days, and the original D-Day objectives were accomplished by D+3.

Pointe du Hoc

The massive concrete cliff-top gun emplacement at Pointe du Hoc was the target of the 2nd Ranger Battalion, commanded by James Earl Rudder. The task was to scale the 30 metre (100 ft) cliffs under enemy fire with ropes and ladders, and then attack and destroy the German coastal defense guns, which were thought to command the Omaha and Utah landing areas. The Ranger commanders did not know that the guns had been moved prior to the attack, and they had to press farther inland to find them but eventually destroyed them. However, the beach fortifications themselves were still vital targets since a single artillery forward observer based there could have called down accurate fire on the U.S. beaches. The Rangers were eventually successful, and captured the fortifications. They then had to fight for two days to hold the location, losing more than 60% of their men.

Utah Beach

Casualties on Utah Beach, the westernmost landing zone, were the lightest of any beach, with 197 out of the roughly 23,000 troops that landed. The 4th Infantry Division troops landing at Utah Beach found themselves in the wrong positions because of a current that pushed their landing craft to the southeast. Instead of landing at Tare Green and Uncle Red sectors, they came ashore at Victor sector, which was lightly defended, and as a result, relatively little German opposition was encountered. The 4th Infantry Division was able to press inland relatively easily over beach exits that had been seized from the inland side by the 502nd and 506th Parachute Infantry Regiments of the 101st Airborne Division. This was partially by accident, because their planned landing was further down the beach (Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr, the Asst. Commander of 4th Division, upon discovering the landings were off course, was famous for stating "We will start the war from right here.") . By early afternoon, the 4th Infantry Division had succeeded in linking up with elements of the 101st. American casualties were light, and the troops were able to press inward much faster than expected, making it a near-complete success.

War memorials and tourism

The beaches at Normandy are still referred to on maps and signposts by their invasion codenames. There are several vast cemeteries in the area. The American cemetery, in Colleville-sur-Mer, contains row upon row of identical white crosses and Stars of David, immaculately kept, commemorating the American dead. Commonwealth graves, in many locations, use white headstones engraved with the person's religious symbol and their unit insignia. The largest cemetery in Normandy is the La Cambe German war cemetery, which features granite stones almost flush with the ground and groups of low-set crosses. There is also a Polish cemetery.

Streets near the beaches are still named after the units that fought there, and occasional markers commemorate notable incidents. At significant points, such as Pointe du Hoc and Pegasus Bridge, there are plaques, memorials or small museums. The Mulberry harbour still sits in the sea at Arromanches. In Sainte-Mère-Église, a dummy paratrooper hangs from the church spire. On Juno Beach, the Canadian government has built the Juno Beach Information Centre, commemorating one of the most significant events in Canadian military history. In Caen is a large Museum for Peace, which is dedicated to peace generally, rather than only to the battle.

See also

References

- ^ Hakim, Joy (1995). A History of Us: War, Peace and all that Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 157–161. ISBN 0-19-509514-6.

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen E. (1994). D-Day. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80137-X.

- ^ Frequently Asked Questions for D-Day and the Battle of Normandy.

- ^ a b c d e f "Britannica guide to D-Day 1944". Retrieved 2007-10-30. Also Keegan, John:The Second World War[page needed]. Cite error: The named reference "DDayFAQ" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Britannica guide to D-Day 1944". Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ^ "Britannica guide to D-Day 1944". Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ^ Vet Affairs, 21(1), March 2005. PDF copy

- ^ a b c d e Map 81, M.R.D. Foot, I.C.B. Dear, ed. (2005). The Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford University Press. p. 663. ISBN 9-780192-806666.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Bradley, John H. (2002). The Second World War: Europe and the Mediterranean. Square One Publishers. p. 290. ISBN 0757001629. Retrieved 2007-11-16.

- ^ Wilmot, Chester (1952). The Struggle for Europe. ISBN 1853266779.

- ^ Tippelskirch, Kurt von, Gechichte der Zweiten Weltkrieg. 1956

- ^ La Seconde Guerre Mondiale – Hors-série Images Doc ISSN 0995-1121 – June 2004

- ^ Verlaine originally wrote, "Blessent mon coeur" (wound my heart). The BBC replaced Verlaine's original words with the slightly modified lyrics of a song entitled Verlaine (Chanson d'Autome) by Charles Trenet.

- ^ a b M.R.D. Foot, SOE, BBC Publications 1984, ISBN 0-563-20193-2. p. 143.

- ^ Ian Holm. (Documentary). UK: BBC. Event occurs at 56:03–56:55.

{{cite AV media}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Stacey, C.P. Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Volume III: The Victory Campaign

- ^ Martin, Charles Cromwell Battle Diary (Dundurn Press, Toronto, 1994) ISBN 1-55002-213-X p.16

Bibliography

- Ambrose, Stephen. D-Day June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II. New york: Simon & Schuster, 1995. ISBN 0671884034.

- Badsey, Stephen. Normandy 1944: Allied Landings and Breakout. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1990. ISBN 978-0850459210.

- D'Este, Carlo. Decision in Normandy: The Unwritten Story of Montgomery and the Allied Campaign. London: William Collins Sons, 1983. ISBN 0002170566.

- Foot, M. R. D. SOE: An Outline History of the Special Operations Executive 1940–46.. BBC Publications, 1984. ISBN 0563201932.

- Ford, Ken. D-Day 1944 (3): Sword Beach & the British Airborne Landings. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002. ISBN 978-1841763668.

- Ford, Ken. D-Day 1944 (4): Gold & Juno Beaches. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002. ISBN 978-1841763682.

- Hamilton, Nigel. "Montgomery, Bernard Law" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 019861411X, ISBN 0198613512.

- Herington, John. Air Power Over Europe, 1944–1945, 1st edition (Official History of Australia in the Second World War Volume IV). Canberra: Australian War Memorial 1963.

- Holderfield, Randal J., and Michael J. Varhola. D-Day: The Invasion of Normandy, June 6, 1944. Mason City, Iowa: Savas Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1882810457, ISBN 1882810465.

- Keegan, John. The Second World War. London: Hutchinson, 1989. ISBN 0091740118.

- Keegan, John. Six Armies in Normandy: From D-Day to the Liberation of Paris. New York: Penguin Books, 1994. ISBN 0140235426.

- Kershaw, Alex. The Bedford Boys: One American Town's Ultimate D-Day Sacrifice. Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo Press, 2003. ISBN 0306813556.

- "Morning: Normandy Invasion (June–August 1944)". The World at War episode 17. B Btish Broadcasting Corporation. 1974.

- Neillands, Robin. The Battle of Normandy, 1944. London: Cassell, 2002. ISBN 0304358371.

- Rozhnov, Konstantin. Who won World War II?. BBC News, 5 May 2005.

- Ryan, Cornelius. The Longest Day, 2nd ed. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1959. ISBN 0-671-20814-4.

- Stacey, C.P. Canada's Battle in Normandy: The Canadian Army's Share in the Operations, 6 June–1 September 1944. Ottawa: King's Printer, 1946.

- Stacey, C.P. (1960). Volume III. The Victory Campaign, The Operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War. Ottawa: Department of National Defence.

- Tute, Warren, John Costello, Terry Hughes. D-Day. London: Pan Books Ltd, 1975. ISBN 0330244183.

- Warner, Phillip. The D-Day Landings. Pen and Sword Books Ltd, 2004. ISBN 1844151093.

- Whitlock, Flint. The Fighting First: The Untold Story of The Big Red One on D-Day. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 2004. ISBN 081334218X.

- Wilmot, Chester. (Written in part by Christopher Daniel McDevitt.) The Struggle For Europe. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions Ltd, 1997. ISBN 1853266779.

- Zaloga, Steven J. D-Day 1944 (1): Omaha Beach. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2003. ISBN 978-1841763675.

- Zaloga, Steven J. D-Day 1944 (2): Utah Beach & the US Airborne Landings. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2004. ISBN 978-1841763651.

- Zetterling, Niklas. Normandy 1944: German Military Organisation, Combat Power and Organizational Effectiveness. Winnipeg: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing Inc., 2000. ISBN 0921991568.

External links

- Stacey, Colonel Charles Perry. "Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War: Volume III. The Victory Campaign: The operations in North-West Europe 1944-1945" (PDF). The Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery Ottawa. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|origdate=ignored (|orig-date=suggested) (help) - American D-Day: Omaha Beach, Utah Beach & Pointe du Hoc

- Neptune Operations Plan

- Debriefing Conference Operation Neptune

- US report on Neptune

- D-Day : Etat des Lieux - 6 June 1944 and Battle of Normandy

- Naval details for Overlord

- HMS Tanatside

- Encyclopaedia Britannica

- Australians and D-Day

- Operation Overlord

- Military history of Normandy

- World War II operations and battles of Europe

- Battles and operations of World War II

- Battle for Caen

- Battles involving Canada

- Battles involving France

- Battles involving Germany

- Battles involving the United Kingdom

- Battles involving the United States

- Crime of aggression