2001 Nisqually earthquake

A stretch of Washington State Route 302 near Allyn, Washington, damaged after the earthquake | |

| UTC time | 2001-02-28 18:54:32 |

|---|---|

| ISC event | 1780664 |

| USGS-ANSS | ComCat |

| Local date | February 28, 2001 |

| Local time | 10:54:32 a.m.[1] |

| Magnitude | 6.8 Mw[1] |

| Depth | 57 km (35 mi)[1] |

| Epicenter | 47°11′N 122°40′W / 47.19°N 122.66°W[1] |

| Type | Normal[2] |

| Areas affected | Pacific Northwest |

| Total damage | $1–4 billion[3] |

| Max. intensity | MMI VIII (Severe)[4] |

| Peak acceleration | 0.3 g[4] |

| Tsunami | No |

| Casualties | 1 dead (heart attack), 400 injured[3] |

The 2001 Nisqually earthquake occurred at 10:54:32 local time on February 28, 2001, and lasted nearly a minute.[5] The intraslab earthquake had a moment magnitude of 6.8 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of VIII (Severe). The epicenter was in the southern Puget Sound, northeast of Olympia, but the shock was felt in Oregon, British Columbia, eastern Washington, and Idaho.[6] This was the most recent of several large earthquakes that occurred in the Puget Sound region over a 52-year period and caused property damage valued at $1–4 billion. One person died of a heart attack and several hundred were injured.

Tectonic setting

[edit]The Puget Sound area is prone to deep earthquakes due to the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate's subduction under the North American plate at 3.5 to 4.5 cm a year[6] as part of the Cascadia subduction zone. Three types of earthquake are observed in the area: rare megathrust events, such as the 1700 Cascadia earthquake, shallow events within the North American plate and deeper intraslab events within the Juan de Fuca plate as it sinks into the mantle. The third type of earthquake is the one that has led to the greatest amount of damage. Significant intraslab earthquakes occurred in the same general region on April 29, 1965 (magnitude 6.7, depth 59 km (37 mi)), and April 13, 1949 (magnitude 6.7, depth 50 km (31 mi)).[7]

Earthquake

[edit]The earthquake was an intraslab event within the Juan de Fuca plate. It was a result of normal faulting within the descending slab, but it has not been possible to determine which of the two possible fault planes indicated by the focal mechanism is correct.[7][2]

Damage

[edit]

Although there were no directly related deaths, local news outlets reported that there was one death from a heart attack.[8] About 400 people were injured.[8] Most of the property damage occurred very near the epicenter or in unreinforced concrete or masonry buildings, such as those in the First Hill, Pioneer Square, and SoDo neighborhoods of Seattle. The Trinity Parish Church on First Hill was severely damaged.[9] The air traffic control tower at Seattle–Tacoma International Airport was heavily damaged; it has since been replaced with a more earthquake-resistant tower. The quake splintered a buttress under the dome of the capitol building in Olympia, but previous earthquake-resistance work prevented more serious harm to the building.[10] Additionally, power outages affected downtown Seattle.[11] The U.S. Military's Ft. Lewis and McChord Air Force Base received damage and there was very slight damage in Victoria, British Columbia.[12]

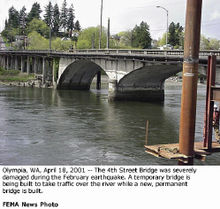

Following the quake, many buildings and structures in the area were closed temporarily for inspection. This included several bridges, all state offices in Olympia, and Boeing's factories in the Seattle area. Various schools in the state also closed for the day. The Fourth Avenue Bridge in downtown Olympia was heavily damaged and was later torn down and re-built.[13][14] In Seattle, the Alaskan Way Viaduct and its seawall were damaged, forcing the viaduct to close for emergency repairs and ultimately factoring into the decision to replace the viaduct with the SR 99 Tunnel and an expanded Alaskan Way on the footprint of the old viaduct.[15] The new tunnel is designed to withstand a 9.0 MW earthquake.[16]

Approximately $305 million of insured losses and a total of $2 billion worth of damage was caused in the state of Washington. The area was declared a natural disaster area by president George W. Bush and was therefore able to receive federal recovery assistance. The number of businesses in the heavily affected region was relatively small.[17] At least 20% of businesses surrounding the heavily affected area took direct losses, while 2% had direct losses of over $10,000. None of these businesses received money for direct damage from federal aid or insurance.[17]

Many businesses did not receive any aid at all. Those that did receive aid had no help with indirect losses. Indirect losses varied from inventory or data corruption, disruption in the workplace, productivity, etc. Data and inventory losses were possibly the most damaging, especially for retail stores. Retail stores lost inventory as well as people's interest for a period of time after the quake. One of the vital elements to prevent damage and injury were well structured buildings. This can prevent the loss of life as well as inventory.[17] Businesses that did not sustain very much damage also gained a sense of security that may be unreliable as the moment magnitude was high but the hypocenter was deep under the earth. This earthquake was a 6.8 moment magnitude that caused $2 billion damage while the Northridge earthquake was a 6.7 moment magnitude, but caused more than $20 billion worth of damage as the hypocenter of the Northridge earthquake was much shallower and closer to the surface of the earth.[17][18]

Ground effects

[edit]Named after the Nisqually Delta, this earthquake hit the southern end of Puget Sound causing damage to the ports of Seattle and Tacoma.[19][8] In the month following the earthquake, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the USGS assembled a team to map the bathymetry of the deltas near the epicenter. This revealed multiple submarine failures on the Puyallup and Duwamish delta fronts. In other areas liquefaction, sand boils, landslides, and soil slumping occurred.[19] Liquefaction was also determined to be a main contributor to increased stream flows. With multiple stream gauges collecting data before and after the earthquake there was a regular pattern of higher increased stream flow around areas where liquefaction occurred.[20] Soil liquefaction was also observed at the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge causing damage to the buildings within.[21]

Response

[edit]A rapid response plan was developed a year later. The region realized how it had avoided a potentially extremely damaging catastrophe. Many businesses, organizations, and hospitals were asked to sign a regional disaster plan, allowing disaster relief teams to locate and aid places much faster than before. The regional plan would also facilitate directing limited resources to places with greatest immediate need.[6][22]

See also

[edit]- List of earthquakes in 2001

- List of earthquakes in the United States

- List of earthquakes in Washington

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d ISC (2015), ISC-GEM Global Instrumental Earthquake Catalogue (1900–2009), Version 2.0, International Seismological Centre

- ^ a b Ichinose, G.A.; Thio, H.K.; Somerville, P.G. (2004). "Rupture process and near‐source shaking of the 1965 Seattle‐Tacoma and 2001 Nisqually, intraslab earthquakes". Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth. 31 (10): n/a. Bibcode:2004GeoRL..3110604I. doi:10.1029/2004GL019668.

- ^ a b PAGER-CAT Earthquake Catalog, Version 2008_06.1, United States Geological Survey, September 4, 2009, archived from the original on March 13, 2020

- ^ a b "M6.8 – Puget Sound region, Washington". United States Geological Survey.

- ^ McNair-Huff, Rob & Natalie (2016). Washington Disasters. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 163. ISBN 978-1-4930-1322-7.

- ^ a b c McDonough, P. W., ed. (2002), The Nisqually, Washington, Earthquake of February 28, 2001, Open-File Report 2002-346, American Society of Civil Engineers, pp. 28, 29, ISBN 978-0-7844-7516-4

- ^ a b Bustin, A; Hyndman, R.D.; Lambert, A.; Ristau, J.; He, J.; Dragert, H.; Vand der Kooij, M. (2004). "Fault Parameters of the Nisqually Earthquake Determined from Moment Tensor Solutions and the Surface Deformation from GPS and InSAR". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 94 (2): 363–376. Bibcode:2004BuSSA..94..363B. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1004.9133. doi:10.1785/0120030073.

- ^ a b c "A Comparison of the February 28, 2001, Nisqually, Washington, and January 17, 1994, Northridge, California Earthquakes". Southern California Earthquake Center.

- ^ Highland, Lynn M. (2002). An Account of Preliminary Landslide Damage and Losses Resulting from the February 28, 2001, Nisqually, Washington, Earthquake. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved August 15, 2009.

- ^ David Postman (March 5, 2001). "Capitol did 'remarkably well'". The Seattle Times. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ Linn, Allison (February 28, 2001). "Bill Gates speech interrupted by quake". Associated Press. Retrieved March 30, 2007.

- ^ Earthquakes Canada – Report (2001-02-28). Accessed January 23, 2009.

- ^ "Fourth Avenue bridge: Bridge over rubbled water". The Olympian. 2002. Archived from the original on November 3, 2001. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ "Quake Capsules-Fourth Avenue Bridge". The Olympian. September 2, 2001. Archived from the original on November 21, 2001. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ "About the Alaskan Way Viaduct and Seawall". WSDOT. Archived from the original on August 29, 2012. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ "Tunneling into the numbers" (PDF). Washington State Department of Transportation. May 2017. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 4, 2020. Retrieved July 19, 2019.

- ^ a b c d Meszaros, J.; Fiegener, M. (2002), Effects of the 2001 Nisqually Earthquake on Small Businesses in Washington State (PDF), United States Department of Commerce, archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2015, retrieved April 1, 2014

- ^ "Resilient Washington State" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on April 7, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

- ^ a b Nisqually Basin Bibliography: Science, Resource Management, Land Use, and Public Policy.

- ^ Montgomery, D. R.; Greenberg, H. M.; Smith, D. T. (2003), "Streamflow response to the Nisqually earthquake", Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 209 (1–2): 19–28, Bibcode:2003E&PSL.209...19M, doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(03)00074-8

- ^ USFWS (2001), Earthquake Rattles Nisqually Refuge (PDF), United States Fish and Wildlife Service, p. 5

- ^ "On Nisqually Quake anniversary, region set to adopt rapid response pact; County repairs damage". Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2014.

External links

[edit]- M 6.8 – Puget Sound region, Washington from the USGS

- 15 years after the Nisqually Earthquake, King County prepares for "the big one" – King County, Washington

- Special Coverage: Ash Wednesday Quake – Seattle Weekly

- The International Seismological Centre has a bibliography and/or authoritative data for this event.