Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition

The Niedermayer–Hentig Expedition, also known as the Kabul Mission, was a diplomatic mission to Afghanistan sent by the Central Powers in 1915–1916. The purpose was to encourage Afghanistan to declare full independence from the British Empire, enter World War I on the side of the Central Powers, and attack British India. The expedition was part of the Hindu–German Conspiracy, a series of Indo-German efforts to provoke a nationalist revolution in India. Nominally headed by the exiled Indian prince Raja Mahendra Pratap, the expedition was a joint operation of Germany and Turkey and was led by the German Army officers Oskar Niedermayer and Werner Otto von Hentig. Other participants included members of an Indian nationalist organisation called the Berlin Committee, including Maulavi Barkatullah and Chempakaraman Pillai, while the Turks were represented by Kazim Bey, a close confidante of Enver Pasha.

Britain saw the expedition as a serious threat. Britain and its ally, the Russian Empire, unsuccessfully attempted to intercept it in Persia during the summer of 1915. Britain waged a covert intelligence and diplomatic offensive, including personal interventions by the Viceroy Lord Hardinge and King George V, to maintain Afghan neutrality.

The mission failed in its main task of rallying Afghanistan, under Emir Habibullah Khan, to the German and Turkish war effort, but it influenced other major events. In Afghanistan, the expedition triggered reforms and drove political turmoil that culminated in the assassination of the Emir in 1919, which in turn precipitated the Third Anglo-Afghan War. It influenced the Kalmyk Project of nascent Bolshevik Russia to propagate socialist revolution in Asia, with one goal being the overthrow of the British Raj. Other consequences included the formation of the Rowlatt Committee to investigate sedition in India as influenced by Germany and Bolshevism, and changes in the Raj's approach to the Indian independence movement immediately after World War I.

The decryption of the Zimmermann telegram was possible after the failure of the Niedermayer-Hentig Expedition to Afghanistan, when Wilhelm Wassmuss abandoned his codebook, which the Allies later recovered, and allowed the British to decrypt the Zimmermann telegram.

Background

[edit]In August 1914, World War I began when alliance obligations arising from the war between Serbia and Austria-Hungary brought Germany and Russia to war, while Germany's invasion of Belgium directly triggered Britain's entry. After a series of military events and political intrigues, Russia declared war on Turkey in November. Turkey then joined the Central Powers in fighting the Entente Powers. In response to the war with Russia and Britain, and further motivated by its alliance with Turkey, Germany accelerated its plans to weaken its enemies by targeting their colonial empires, including Russia in Turkestan and Britain in India, using political agitation.[1]

Germany began by nurturing its pre-war links with Indian nationalists, who had for years used Germany, Turkey, Persia, the United States, and other countries as bases for anti-colonial work directed against Britain. As early as 1913, revolutionary publications in Germany began referring to the approaching war between Germany and Britain and the possibility of German support for Indian nationalists.[2] During the early months of the war, German newspaper devoted considerable coverage to social problems in India and instances of British economic exploitation.[2]

German Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg encouraged this activity.[3] The effort was led by prominent archaeologist and historian Max von Oppenheim, who headed the new Intelligence Bureau for the East and formed the Berlin Committee, which was later renamed the Indian Independence Committee. The Berlin Committee offered money, arms, and military advisors according to plans made by the German Foreign Office and Indian revolutionaries-in-exile such as members of the Ghadar Party in North America. The planners hoped to trigger a nationalist rebellion using clandestine shipments of men and arms sent to India from elsewhere in Asia and from the United States.[3][4][5][6]

In Turkey and Persia, nationalist work had begun by 1909, under the leadership of Sardar Ajit Singh and Sufi Amba Prasad.[7] Reports from 1910 indicate that Germany was already contemplating efforts to threaten India through Turkey, Persia, and Afghanistan. Germany had built close diplomatic and economic relationships with Turkey and Persia from the late 19th century. Von Oppenheim had mapped Turkey and Persia while working as a secret agent.[8] The Kaiser toured Constantinople, Damascus, and Jerusalem in 1898 to bolster the Turkish relationship and to portray solidarity with Islam, a religion professed by millions of subjects of the British Empire in India and elsewhere. Referring to the Kaiser as Haji Wilhelm, the Intelligence Bureau for the East spread propaganda throughout the region, fostering rumours that the Kaiser had converted to Islam following a secret trip to Mecca and portraying him as a saviour of Islam.[1]

Led by Enver Pasha, a coup in Turkey in 1913 sidelined Sultan Mehmed V and concentrated power in the hands of a junta. Despite the secular nature of the new government, Turkey retained its traditional influence over the Muslim world. Turkey ruled Hejaz until the Arab Revolt of 1916 and controlled the Muslim holy city of Mecca throughout the war. The Sultan's title of Caliph was recognised as legitimate by most Muslims, including those in Afghanistan and India.[1]

Once at war, Turkey joined Germany in taking aim at the opposing Entente Powers and their extensive empires in the Muslim world. Enver Pasha had the Sultan proclaim jihad.[1] His hope was to provoke and aid a vast Muslim revolution, particularly in India. Translations of the proclamation were sent to Berlin for propaganda purposes, for distribution to Muslim troops of the Entente Powers.[1] However, while widely heard, the proclamation did not have the intended effect of mobilising global Muslim opinion on behalf of Turkey or the Central Powers.

Early in the war, the Emir of Afghanistan declared neutrality.[9] The Emir feared the Sultan's call to jihad would have a destabilising influence on his subjects. Turkey's entry into the war aroused widespread nationalist and pan-Islamic sentiments in Afghanistan and Persia.[9] The Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907 designated Afghanistan to the British sphere of influence. Britain nominally controlled Afghanistan's foreign policy and the Emir received a monetary subsidy from Britain. In reality, however, Britain had almost no effective control over Afghanistan. The British perceived Afghanistan to be the only state capable of invading India, which remained a serious threat.[10]

First Afghan expedition

[edit]In the first week of August 1914, the German Foreign Office and members of the military suggested attempting to use the pan-Islamic movement to destabilise the British Empire and begin an Indian revolution.[1] The argument was reinforced by Germanophile explorer Sven Hedin in Berlin two weeks later. General Staff memoranda in the last weeks of August confirmed the perceived feasibility of the plan, predicting that an invasion by Afghanistan could cause a revolution in India.[1]

With the outbreak of war, revolutionary unrest increased in India. Some Hindu and Muslim leaders secretly left to seek the help of the Central Powers in fomenting revolution.[2][10] The pan-Islamic movement in India, particularly the Darul Uloom Deoband, made plans for an insurrection in the North-West Frontier Province, with support from Afghanistan and the Central Powers.[11][12] Mahmud al Hasan, the principal of the Deobandi school, left India to seek the help of Galib Pasha, the Turkish governor of Hijaz, while another Deoband leader, Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi, travelled to Kabul to seek the support of the Emir of Afghanistan. They initially planned to raise an Islamic army headquartered at Medina, with an Indian contingent at Kabul. Mahmud al Hasan was to command this army.[12] While at Kabul, Maulana came to the conclusion that focusing on the Indian Freedom Movement would best serve the pan-Islamic cause.[13] Ubaidullah proposed to the Afghan Emir that he declare war against Britain.[14][15] Maulana Abul Kalam Azad was also involved in the movement prior to his arrest in 1916.[11]

Enver Pasha conceived an expedition to Afghanistan in 1914. He envisioned it as a pan-Islamic venture directed by Turkey, with some German participation. The German delegation to this expedition, chosen by Oppenheim and Zimmermann, included Oskar Niedermayer and Wilhelm Wassmuss.[9] An escort of nearly a thousand Turkish troops and German advisers was to accompany the delegation through Persia into Afghanistan, where they hoped to rally local tribes to jihad.[16]

In an ineffective ruse, the Germans attempted to reach Turkey by travelling overland through Austria-Hungary in the guise of a travelling circus, eventually reaching neutral Romania. Their equipment, arms, and mobile radios were confiscated when Romanian officials discovered the wireless aerials sticking out through the packaging of the "tent poles".[16] Replacements could not be arranged for weeks; the delegation waited at Constantinople. To reinforce the Islamic identity of the expedition, it was suggested that the Germans wear Turkish army uniforms, but they refused. Differences between Turkish and German officers, including the reluctance of the Germans to accept Turkish control, further compromised the effort.[17] Eventually, the expedition was aborted.

The attempted expedition had a significant consequence. Wassmuss left Constantinople to organise the tribes in south Persia to act against British interests. While evading British capture in Persia, Wassmuss inadvertently abandoned his codebook. Its recovery by Britain allowed the Allies to decipher German communications, including the Zimmermann Telegram in 1917. Niedermayer led the group following Wassmuss's departure.[17]

Second expedition

[edit]In 1915, a second expedition was organised, mainly through the German Foreign Office and the Indian leadership of the Berlin Committee. Germany was now extensively involved in the Indian revolutionary conspiracy and provided it with arms and funds. Lala Har Dayal, prominent among the Indian radicals liaising with Germany, was expected to lead the expedition. When he declined, the exiled Indian prince Raja Mahendra Pratap was named leader.[18]

Composition

[edit]Mahendra Pratap was head of the Indian princely states of Mursan and Hathras. He had been involved with the Indian National Congress in the 1900s, attending the Congress session of 1906. He toured the world in 1907 and 1911, and in 1912 contributed substantial funds to Gandhi's South African movement.[19] Pratap left India for Geneva at the beginning of the war, where he was met by Virendranath Chattopadhyaya of the Berlin Committee. Chattopadhyaya's efforts—along with a letter from the Kaiser—convinced Pratap to lend his support to the Indian nationalist cause,[20] on the condition that the arrangements were made with the Kaiser himself. A private audience with the Kaiser was arranged, at which Pratap agreed to nominally head the expedition.[21][22]

Prominent among the German members of the delegation were Niedermayer and von Hentig.[17] Von Hentig was a Prussian military officer who had served as the military attaché to Beijing in 1910 and Constantinople in 1912. Fluent in Persian, he was appointed secretary of the German legation to Tehran in 1913. Von Hentig was serving on the Eastern front as a lieutenant with the Prussian 3rd Cuirassiers when he was recalled to Berlin for the expedition.

Like von Hentig, Niedermayer had served in Constantinople before the war and spoke fluent Persian and other regional languages. A Bavarian artillery officer and a graduate from the University of Erlangen, Niedermayer had travelled in Persia and India in the two years preceding the war.[17] He returned to Persia to await further orders after the first Afghan expedition was aborted.[17] Niedermayer was tasked with the military aspect of this new expedition as it proceeded through the dangerous Persian desert between British and Russian areas of influence.[19][22][23] The delegation also included German officers Günter Voigt and Kurt Wagner.

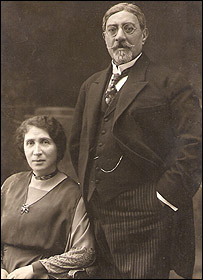

Accompanying Pratap were other Indians from the Berlin Committee, notably Champakaraman Pillai and the Islamic scholar and Indian nationalist Maulavi Barkatullah. Barkatullah had long been associated with the Indian revolutionary movement, having worked with the India House in London and New York from 1903. In 1909, he moved to Japan, where he continued his anti-British activities. Taking the post of Professor of Urdu at Tokyo University, he visited Constantinople in 1911. However, his Tokyo tenure was terminated under diplomatic pressure from Britain. He returned to the United States in 1914, later proceeding to Berlin, where he joined the efforts of the Berlin Committee. Barkatullah had as early as 1895 been acquainted with Nasrullah Khan, the brother of the Afghan Emir, Habibullah Khan.[24]

Pratap chose six Afghan Afridi and Pathan volunteers from the prisoner of war camp at Zossen.[24] Before the mission left Berlin, two more Germans joined the group: Major Dr. Karl Becker, who was familiar with tropical diseases and spoke Persian, and Walter Röhr, a young merchant fluent in Turkish and Persian.[25]

Organisation

[edit]The titular head of the expedition was Mahendra Pratap, while von Hentig was the Kaiser's representative. He was to accompany and introduce Mahendra Pratap and was responsible for the German diplomatic representations to the Emir.[17][22] To fund the mission, 100,000 pounds sterling in gold was deposited in an account at the Deutsche Bank in Constantinople. The expedition was also provided with gold and other gifts for the Emir, including jewelled watches, gold fountain pens, ornamental rifles, binoculars, cameras, cinema projectors, and an alarm clock.[22][25]

Supervision of the mission was assigned to the German Ambassador to Turkey, Hans von Wangenheim, but as he was ill, his functions were delegated to Prince zu Hohenlohe-Langenburg.[19] Following Wangenheim's death in 1915, Count von Wolff-Metternich was designated his successor. He had little contact with the expedition.[19]

Journey

[edit]To evade British and Russian intelligence, the group split up, beginning their journeys on different days and separately making their way to Constantinople.[25] Accompanied by a German orderly and an Indian cook, Pratap and von Hentig began their journey in early spring 1915, travelling via Vienna, Budapest, Bucharest, Sofia, and Adrianople to Constantinople. At Vienna, they were met briefly by the deposed Khedive of Egypt, Abbas Hilmi.[25]

Persia and Isfahan

[edit]Reaching Constantinople on 17 April, the party waited at the Pera Palace Hotel for three weeks while further travel arrangements were made. During this time, Pratap and Hentig met with Enver Pasha and enjoyed an audience with the Sultan. On Enver Pasha's orders, a Turkish officer, Lieutenant Kasim Bey, was deputed to the expedition as the Turkish representative, bearing official letters addressed to the Afghan Emir and the Indian princely states.[26] Two Afghans from the United States also joined the expedition.[26]

The group, now numbering approximately twenty people, left Constantinople in early May 1915. They crossed the Bosphorus to take the unfinished Baghdad Railway to Baghdad. The Taurus Mountains were crossed on horseback, using—as von Hentig reflected—the same route taken by Alexander the Great, Paul the Apostle, and Frederick I.[26] The group crossed the Euphrates at high flood, finally reaching Baghdad towards the end of May.[26]

As Baghdad raised the spectre of an extensive network of British spies, the group again split. Pratap and von Hentig's party left on 1 June 1915 to make their way towards the Persian border. Eight days later they were received by the Turkish military commander Rauf Orbay at the Persian town of Krynd.[26] Leaving Krynd, the party reached Turkish-occupied Kermanshah on 14 June 1915. Some members were sick with malaria and other tropical diseases. Leaving them under the care of Dr. Becker, von Hentig proceeded towards Tehran to decide on the subsequent plans with Prince Heinrich Reuss and Niedermayer.[27]

Persia at the time was divided into British and Russian spheres of influence, with a neutral zone in between. Germany exercised influence over the central parts of the country through their consulate in Isfahan. The local populace and the clergy, opposed to Russian and British semi-colonial designs on Persia, offered support to the mission. Niedermayer and von Hentig's groups reconnoitred Isfahan until the end of June.[28] The Viceroy of India, Lord Hardinge, was already receiving reports of pro-German sympathies among Persian and Afghan tribes. Details of the progress of the expedition were being keenly sought by British intelligence.[25][28] By now, British and Russian columns close to the Afghan border, including the Seistan Force, were hunting for the expedition.[28] If the expedition was to reach Afghanistan, it would have to outwit and outrun its pursuers over thousands of miles in the extreme heat and natural hazards of the Persian desert, while evading brigands and ambushes.[28]

By early July, the sick at Kermanshah had recovered and rejoined the expedition. Camels and water bags were purchased, and the parties left Isfahan separately on 3 July 1915 for the journey through the desert, hoping to rendezvous at Tebbes, halfway to the Afghan border.[28] Von Hentig's group travelled with twelve pack horses, twenty-four mules, and a camel caravan. Throughout the march, efforts were made to throw off the British and Russian patrols. False dispatches spread disinformation on the group's numbers, destination, and intention.[28] To avoid the extreme daytime heat, they travelled by night. Food was found or bought by Persian messengers sent ahead of the party. These scouts also helped identify hostile villages and helped find water. The group crossed the Persian desert in forty nights. Dysentery and delirium plagued the party. Some Persian guides attempted to defect, and camel drivers had to be constantly vigilant for robbers. On 23 July, the group reached Tebbes – the first Europeans after Sven Hedin. They were soon followed by Niedermayer's party, which now included explorer Wilhelm Paschen and six Austrian and Hungarian soldiers who had escaped from Russian prisoner of war camps in Turkestan.[28] The arrival was marked by a grand welcome by the town's mayor.[28] However, the welcome meant the party had been spotted.

East Persian Cordon

[edit]

Still 200 miles from the Afghan border, the expedition now had to race against time. Ahead were British patrols of the East Persia Cordon (later known as the Seistan Force) and Russian patrols. By September, the German codebook lost by Wassmuss had been deciphered, which further compromised the situation. Niedermayer, now in charge, proved to be a brilliant tactician.[29] He sent three feint patrols, one to north-east to draw away the Russian troops and one to the south-east to draw away the British, while a third patrol of thirty armed Persians, led by a German officer—Lieutenant Wagner—was sent ahead to scout the route.[29][30] After leading the Russians astray, the first group was to remain in Persia to establish a secret desert base as a refuge for the main party. After luring away the British, the second group was to fall back to Kermanshah and link with a separate German force under Lieutenants Zugmayer and Griesinger.[31] All three parties were ordered to spread misleading information about their movements to any nomads or villagers they met.[31] Meanwhile, the main body headed through Chehar Deh for the region of Birjand, close to the Afghan frontier.[29][32] The party covered forty miles before it reached the next village, where Niedermayer halted to await word from Wagner's patrol. The villagers were meanwhile barred from leaving. The report from Wagner was bad: His patrol had run into a Russian ambush and the desert refuge had been eliminated.[33] The expedition proceeded towards Birjand using forced marches to keep a day ahead of the British and Russian patrols. Other problems still confronted Niedermayer, among them the opium addiction of his Persian camel drivers. Fearful of being spotted, he had to stop the Persians a number of times from lighting up their pipes. Men who fell behind were abandoned. Some of the Persian drivers attempted to defect. On one occasion, a driver was shot while he attempted to flee and betray the group.[29][34]

Although the town of Birjand was small, it had a Russian consulate. Niedermayer correctly guessed additional British forces were present. He therefore had to decide whether to bypass the town by the northern route, patrolled by Russians, or the southern route, where British patrols were present.[34] He could not send any reconnaissance. His Persian escort's advice that the desert north of Birjand was notoriously harsh convinced him that this would be the route his enemies would least expect him to take. Sending a small decoy party south-east to spread the rumour that the main body would soon follow, Niedermayer headed for the north.[34] His feints and disinformation were taking effect. The pursuing forces were spread thin, hunting for what they believed at times to be a large force. At other times they looked for a second, non-existent German force heading east from Kermanshah.[35] The group now moved both day and night. From nomads, Niedermayer learnt the whereabouts of the British patrols. He lost men through exhaustion, defection, and desertion. On occasions, deserters would take the party's spare water and horses at gunpoint.[36] Nonetheless, by the second week of August the forced march had brought the expedition close to the Birjand-Meshed road, eighty miles from Afghanistan. Here the Kaiser's bulkier and heavier gifts to the Emir, including the German wireless sets, were buried in the desert for later retrieval.[36] Since all caravans entering Afghanistan must cross the road, Niedermayer assumed it was watched by British spies. An advance patrol reported seeing British columns. With scouts on the lookout, the expedition crossed under the cover of night.[36] Only one obstacle, the so-called "Mountain Path", remained before they were clear of the Anglo-Russian cordon. This heavily patrolled path, thirty miles further east, was the site of Entente telegraph lines for maintaining communication with remote posts.[37] However, even here, Niedermayer escaped. His group had covered 255 miles in seven days, through the barren Dasht-e Kavir.[38] On 19 August 1915 the expedition reached the Afghan frontier. Mahendra Pratap's memoirs describe the group as left with approximately fifty men, less than half the number who had set out from Isfahan seven weeks earlier. Dr. Becker's camel caravan was lost and he was later captured by Russians. Only 70 of the 170 horses and baggage animals survived.[29][39]

Afghanistan

[edit]Crossing into Afghanistan, the group found fresh water in an irrigation channel by a deserted hamlet. Albeit teeming with leeches, the water saved the group from dying of thirst. Marching for another two days, they reached the vicinity of Herat, where they made contact with Afghan authorities.[39] Unsure what reception awaited them, von Hentig sent Barkatullah, an Islamic scholar of some fame, to advise the governor that the expedition had arrived and was bearing the Kaiser's message and gifts for the Emir.[29] The governor sent a grand welcome, with noblemen bearing cloths and gifts, a caravan of servants, and a column of hundred armed escorts. The expedition was invited into the city as guests of the Afghan government. With von Hentig in the lead in his Cuirassiers uniform, they entered Herat on 24 August, in a procession welcomed by Turkish troops.[29][40] They were housed at the Emir's provincial palace. They were officially met by the governor a few days later when, according to British agents, von Hentig showed him the Turkish Sultan's proclamation of jihad and announced the Kaiser's promise to recognise Afghan sovereignty and provide German assistance.[41] The Kaiser also promised to grant territory to Afghanistan as far north as Samarkand in Russian Turkestan and as far into India as Bombay.[41]

The Viceroy of India had already warned the Emir of approaching "German agents and hired assassins", and the Emir had promised he would arrest the expedition if it managed to reach Afghanistan. However, under a close watch, the expedition members were given the freedom of Herat. The governor promised to arrange for the 400-mile trip east to Kabul in another two weeks. Suits were tailored and horses given new saddles to make everything presentable for the meeting with the Emir.[41] The southern route and the city of Kandahar were avoided, possibly because Afghan officials wished to prevent fomenting unrest in the Pathan region close to India.[41] On 7 September, the group left Herat for Kabul with Afghan guides on a 24-day trip via the harsher northern route through Hazarajat, over the barren mountains of central Afghanistan.[41] En route the expedition was careful to spend enough money and gold to ensure popularity amongst the local people.[41] Finally, on 2 October 1915, the expedition reached Kabul. It was received with a salaam from the local Turkish community and a Guard of honour from Afghan troops in Turkish uniform.[42] Von Hentig later described receiving cheers and a grand welcome from the inhabitants of Kabul.[41]

Afghan intrigues

[edit]At Kabul, the group was accommodated as state guests at the Emir's palace at Bagh-e Babur.[41] Despite the comfort and the welcome, it was soon clear that they were all but confined. Armed guards were stationed around the palace, ostensibly for "the group's own danger from British secret agents", and armed guides escorted them on their journeys.[43] For nearly three weeks, Emir Habibullah, reportedly in his summer palace at Paghman, responded with only polite noncommittal replies to requests for an audience. An astute politician, he was in no hurry to receive his guests; he used the time to find out as much as he could about the expedition members and liaised with British authorities at New Delhi.[43] It was only after Niedermayer and von Hentig threatened to launch a hunger strike that meetings began.[43] In the meantime, von Hentig learnt as much as he could about his eccentric host. Emir Habibullah was, by all measures, the lord of Afghanistan. He considered it his divine right to rule and the land his property.[43] He owned the only newspaper, the only drug store, and all the automobiles in the country (all Rolls-Royces).[43]

The Emir's brother, Prime Minister Nasrullah Khan, was a man of religious convictions. Unlike the Emir, he fluently spoke Pashto (the local language), dressed in traditional Afghan robes, and interacted more closely with the border tribes. While the Emir favoured British India, Nasrullah Khan was more pro-German in his sympathies.[43] Nasrullah's views were shared by his nephew, Amanullah Khan, the youngest and most charismatic of the Emir's sons.[43] The eldest son, Inayatullah Khan, was in charge of the Afghan army.[43] The mission therefore expected more sympathy and consideration from Nasrullah and Amanullah than from the emir.[43]

Meeting Emir Habibullah

[edit]

On 26 October 1915 the Emir finally granted an audience at his palace at Paghman, which provided privacy from British secret agents.[43] The meeting, which lasted the entire day, began on an uncomfortable note, with Habibullah summing up his views on the expedition in a prolonged opening address:

I regard you as merchants who will spread out your wares before me. Of these goods, I shall choose according to my pleasure and my fancy, taking what I like and rejecting what I do not need.[44]

He expressed surprise that a task as important as the expedition's was entrusted to such young men. Von Hentig had to convince the Emir that the mission did not consider themselves merchants, but instead brought word from the Kaiser, the Ottoman Sultan, and from India, wishing to recognise Afghanistan's complete independence and sovereignty.[44][45] The Kaiser's typewritten letter, which he compared to the handsome greeting received from the Ottomans, failed to settle the Emir's suspicions; he doubted its authenticity. Von Hentig's explanation that the Kaiser had written the letter using the only instrument available at his field headquarters before the group's hurried departure may not have entirely convinced him.[44] Passing along the Kaiser's invitation to join the war on the side of the Central Powers, von Hentig described the war situation as favourable and invited the Emir to declare independence.[44] This was followed by a presentation from Kasim Bey explaining the Ottoman Sultan's declaration of jihad and Turkey's desire to avoid a fratricidal war between Islamic peoples. He passed along a message to Afghanistan similar to the Kaiser's. Barkatullah invited Habibullah to declare war against the British Empire and to come to the aid of India's Muslims. He proposed that the Emir should allow Turco-German forces to cross Afghanistan for a campaign towards the Indian frontier, a campaign which he hoped the Emir would join.[46] Barkatullah and Mahendra Pratap, both eloquent speakers, pointed out the rich territorial gains the Emir stood to acquire by joining the Central Powers.[47]

The Emir's reply was shrewd but frank. He noted Afghanistan's vulnerable strategic position between the two allied nations of Russia and Britain, and the difficulties of any possible Turco-German assistance to Afghanistan, especially given the presence of the Anglo-Russian East Persian Cordon. Further, he was financially vulnerable, dependent on British subsidies and institutions for his fortune and the financial welfare of his army and kingdom.[46] The members of the mission had no immediate answers to his questions regarding strategic assistance, arms, and funds. Merely tasked to entreat the Emir to join a holy war, they did not have the authority to promise anything.[46] Nonetheless, they expressed hopes of an alliance with Persia in the near future (a task Prince Henry of Reuss and Wilhelm Wassmuss worked on), which would help meet the Emir's needs.[48] Although it reached no firm outcome, this first meeting has been noted by historians as being cordial, helping open communications with the Emir and allowing the mission to hope for success.[48]

This conference was followed by an eight-hour meeting in October 1915 at Paghman and more audiences at Kabul.[44] The message was the same as at the first audience. The meetings would typically begin with Habibullah describing his daily routine, followed by words from von Hentig on politics and history. Next the discussions veered towards Afghanistan's position on the propositions of allowing Central Powers troops the right of passage, breaking with Britain, and declaring independence.[47] The expedition members expected a Persian move to the Central side, and held out on hopes that this would convince the Emir to join as well. Niedermayer argued that German victory was imminent; he outlined the compromised and isolated position Afghanistan would find herself in if she was still allied to Britain.[47] At times the Emir met with the Indian and German delegates separately,[47] promising to consider their propositions, but never committing himself. He sought concrete proof that the Turco-German assurances of military and financial assistance were feasible.[47] In a letter to Prince Henry of Reuss in Tehran (a message that was intercepted and delivered to the Russians instead), von Hentig asked for Turkish troops. Walter Röhr later wrote to the prince that a thousand Turkish troops armed with machine guns—along with another German expedition headed by himself—should be able to draw Afghanistan into the war.[49] Meanwhile, Niedermayer advised Habibullah on how to reform his army with mobile units and modern weaponry.[50]

Meetings with Nasrullah

[edit]

While the Emir vacillated, the mission found a more sympathetic and ready audience in the Emir's brother, Prime Minister Nasrullah Khan, and the Emir's younger son, Amanullah Khan.[47] Nasrullah Khan had been present at the first meeting at Paghman. In secret meetings with the "Amanullah party" at his residence, he encouraged the mission. Amanullah Khan gave the group reasons to feel confident, even as rumours of these meetings reached the Emir.[47] Messages from von Hentig to Prince Henry, intercepted by British and Russian intelligence, were subsequently passed on to Emir Habibullah. These suggested that to draw Afghanistan into the war, von Hentig was prepared to organise "internal revulsions" in Afghanistan if necessary.[47][51] Habibullah found these reports concerning, and discouraged expedition members from meeting with his sons except in his presence. All of Afghanistan's immediate preceding rulers save Habibullah's father had died of unnatural causes. The fact that his immediate relatives were pro-German, while he was allied with Britain, gave him justifiable grounds to fear for his safety and his kingdom.[47] Von Hentig described one audience with Habibullah where von Hentig set off his pocket alarm clock. The action, designed to impress Habibullah, instead frightened him; he may have believed it was a bomb about to go off. Despite von Hentig's reassurances and explanations, the meeting was a short one.[49]

During the months that the expedition remained in Kabul, Habibullah fended off pressure to commit to the Central war effort with what has been described as "masterly inactivity".[49] He waited for the outcome of the war to be predictable, announcing to the mission his sympathy for the Central Powers and asserting his willingness to lead an army into India—if and when Turco-German troops were able to offer support. Hints that the mission would leave if nothing could be achieved were placated with flattery and invitations to stay on. Meanwhile, expedition members were allowed to freely venture into Kabul, a liberty which was put to good use on a successful hearts and minds campaign, with expedition members spending freely on local goods and paying cash. Two dozen Austrian prisoners of war who had escaped from Russian camps were recruited by Niedermayer to construct a hospital.[49] Meanwhile, Kasim Bey acquainted himself with the local Turkish community, spreading Enver Pasha's message of unity and Pan-Turanian jihad.[50] Habibullah tolerated the increasingly anti-British and pro-Central tone being taken by his newspaper, Siraj al Akhbar, whose editor—his father-in-law Mahmud Tarzi—had accepted Barkatullah as an officiating editor in early 1916. Tarzi published a series of inflammatory articles by Raja Mahendra Pratap and printed anti-British and pro-Central articles and propaganda. By May 1916, the tone in the paper was deemed serious enough for the Raj to intercept the copies intended for India.[49][52]

Through German links with Ottoman Turkey, the Berlin Committee at this time established contact with Mahmud al Hasan at Hijaz, while the expedition itself was now met at Kabul by Ubaidullah Sindhi's group.[52][53]

Political developments

[edit]Political events and progress attained during December 1915 allowed the mission to celebrate at Kabul on Christmas Day with wine and cognac left behind by the Durand mission forty years previously, which Habibullah lay at their disposal. These events included the foundation of the Provisional Government of India that month and a shift from the Emir's usual aversive stance to an offer of discussions on a German-Afghan treaty of friendship.[50][54]

In November, the Indian members decided to take a political initiative which they believed would convince the Emir to declare jihad, and if that proved unlikely, to have his hand forced by his advisors.[50][54] On 1 December 1915, the Provisional Government of India was founded at Habibullah's Bagh-e-Babur Palace, in the presence of the Indian, German, and Turkish members of the expedition. This revolutionary government-in-exile was to take charge of an independent India when the British authority had been overthrown.[50] Mahendra Pratap was proclaimed president, Barkatullah the prime minister, the Deobandi leader Maulana Ubaidullah Sindhi the minister for India, Maulavi Bashir the war minister, and Champakaran Pillai the foreign minister.[55] Support was obtained from Galib Pasha for proclaiming jihad against Britain, while recognition was sought from Russia, Republican China, and Japan.[56] After the February Revolution in Russia in 1917, Pratap's government corresponded with the nascent Bolshevik government in an attempt to gain their support. In 1918, Mahendra Pratap met Trotsky in Petrograd before meeting the Kaiser in Berlin, urging both to mobilise against British India.[54][57]

Draft Afghan-German friendship treaty

[edit]December 1915 also saw concrete progress on the mission's Turco-German objective. The Emir informed von Hentig he was ready to discuss a treaty of Afghan-German friendship, but said it would take time and require extensive historical research. Work on the treaty began with drafts proposed by von Hentig. The final draft of ten articles presented on 24 January 1916 included clauses recognising Afghan independence, a declaration of friendship with Germany, and establishment of diplomatic relations. Von Hentig was to be accredited the Embassy Secretary of the German Empire. In addition, the treaty would guarantee German assistance against Russian and British threats if Afghanistan joined the war on the Central side.[54] The Emir's army was to be modernised, with Germany providing 100,000 modern rifles, 300 artillery pieces, and other modern warfare equipment. The Germans were to be responsible for maintaining advisors and engineers, and to maintain an overland supply route through Persia for arms and ammunition. Further, the Emir was to be paid £1,000,000.[54] Both von Hentig and Niedermayer signed this document which created—as von Hentig argued in a telegram to the Foreign Office—an initial basis to prepare for an Afghan invasion of India. Niedermayer explained that the Emir intended to begin his campaign as soon as Germany could make available 20,000 troops to protect the Afghan-Russian front,[58] and asked for urgently for wireless sets, a substantial shipment of arms, and at least a million pounds initial funding. He judged conditions to be ideal for an offensive into India, and informed the general staff to expect the campaign to begin in April.[58]

Mission's conclusion

[edit]In the end, Emir Habibullah returned to his vacillating inactivity. He was aware the mission had found support within his council and had excited his volatile subjects. Four days after the draft treaty was signed, Habibullah called for a durbar, a grand meeting where a jihad was expected to be called. Instead, Habibullah reaffirmed his neutrality, explaining that the war's outcome was still unpredictable and that he stood for national unity.[58] Throughout the spring of 1916, he continuously deflected the mission's overtures and gradually increased the stakes, demanding that India rise in revolution before he began his campaign. It was clear to Habibullah that for the treaty to hold any value, it required the Kaiser's signature, and that for Germany to even attempt to honour the treaty, she would have to be in a strong position in the war. It was a good insurance policy for Habibullah.[58]

Meanwhile, he had received worrying British intelligence reports that said he was in danger of being assassinated and his country may face a coup d'état. His tribesmen were unhappy at Habibullah's perceived subservience to the British, and his council and relatives openly spoke of their suspicions at his inactivity. Habibullah began purging his court of officials who were known to be close to Nasrullah and Amanullah. He recalled emissaries he had sent to Persia for talks with Germany and Turkey for military aid.[58] Meanwhile, the war took a turn for the worse for the Central Powers. The Arab revolt against Turkey and the loss of Erzurum to the Russians ended the hopes of sending a Turkish division to Afghanistan.[58] The German influence in Persia also declined rapidly, ending the hopes that Goltz Pasha could lead a Persian volunteer division into Afghanistan.[59] The mission came to realise that the Emir deeply mistrusted them. A further attempt by British intelligence to feed false information to the mission, purportedly originating from Goltz Pasha, convinced von Hentig of the Emir's lack of trust.[59] A last offer was made by Nasrullah in May 1916 to remove Habibullah from power and lead the frontier tribes in a campaign against British India.[59] However, von Hentig knew it would come to nothing, and the Germans left Kabul on 21 May 1916. Niedermayer instructed Wagner to stay in Herat as a liaison officer. The Indian members also stayed, persisting in their attempts at an alliance.[59][60][61]

Though ancient rules of hospitality had protected the expedition, they knew that once they were out of the Emir's lands, the Anglo-Russian forces as well as the marauding tribesmen of Persia would chase them mercilessly. The party split up into several groups, each independently making its way back to Germany.[60] Niedermayer headed west, attempting to run the Anglo-Russian Cordon and escape through Persia, while von Hentig made for the route over the Pamir Mountains towards Chinese Central Asia. Having served in Peking before the war, von Hentig was familiar with the region and planned to make Yarkand a base from which to make a last attempt to create local Muslim unrest against Anglo-Russian interests in the region.[60] He later escaped over the Hindu Kush, avoiding his pursuers for 130 days as he made his way on foot and horseback through Chinese Turkestan, over the Gobi Desert, and through China and Shanghai. From there, he stowed away on an American vessel to Honolulu. Following the American declaration of war, he was exchanged as a diplomat. Travelling via San Francisco, Halifax, and Bergen, he finally reached Berlin on 9 June 1917.[62] Meanwhile, Niedermayer escaped towards Persia through Russian Turkestan. Robbed and left for dead, a wounded Niedermayer was at times reduced to begging before he finally reached friendly lines, arriving in Tehran on 20 July 1916.[62][63] Wagner left Herat on 25 October 1917, making his way through northern Persia to reach Turkey on 30 January 1918. At Chorasan, he tried to rally Persian democratic and nationalist leaders, who promised to raise an army of 12,000 if Germany provided military assistance.[61]

Mahendra Pratap attempted to seek an alliance with Tsar Nicholas II from February 1916, but his messages remained unacknowledged.[56] The 1917 Kerensky government refused a visa to Pratap, aware that he was considered a "dangerous seditionist" by the British government.[56] Pratap was able to correspond more closely with Lenin's Bolshevik government. At the invitation of Turkestan authorities, he visited Tashkent in February 1918. This was followed by a visit to Petrograd, where he met Trotsky. He and Barkatullah remained in touch with the German government and with the Berlin Committee through the latter's secret office in Stockholm. After Lenin's coup, Pratap at times acted as liaison between the Afghan government and the Germans, hoping to revive the Indian cause. In 1918, Pratap suggested to Trotsky a joint German-Russian invasion of the Indian frontiers. He recommended a similar plan to Lenin in 1919. He was accompanied in Moscow by Indian revolutionaries of the Berlin Committee, who were at the time turning to communism.[56][61]

British counter efforts

[edit]Seistan Force

[edit]

The East Persian Cordon (later called the Seistan Force), consisting of British Indian Army troops, was established in the Sistan province of south-east Persia to prevent the Germans from crossing into Afghanistan and to protect British supply caravans in Sarhad from Damani, Reki, and Kurdish Balushi tribes who might be tempted by German gold.[64] The 2nd Quetta Brigade, a small force maintained in Western Balochistan since the beginning of the war, was expanded in July 1915 and became the East Persia Cordon, with troops stationed from Russian Turkestan to Baluchistan. A similar Russian cordon was established to prevent infiltration into north-west Afghanistan. From March 1916 the force was renamed the Seistan Force, under the direction of General George Macaulay Kirkpatrick, the Chief of the General Staff in India. The cordon was initially under the command of Colonel J. M. Wilkeley before it was taken over by Reginald Dyer in February 1916.[65] The cordon's task was to "intercept, capture or destroy any German parties attempting to enter Sistan or Afghanistan",[65] to establish an intelligence system, and to watch the Birjand-Merked road. Persian subjects were not to be targeted as long as they were not accompanying Germans or acting as their couriers, and as long as Persia remained neutral.[65] Following the Revolution in Russia, the Malleson Mission was sent to Trans-Caspia and the Seistan Force became the main line of communication for the mission. With the withdrawal of the force from Trans-Caspia, the troops in Persia were withdrawn; the last elements left in November 1920.

Intelligence efforts

[edit]British efforts against the conspiracy and the expedition began in Europe. Even before Mahendra Pratap met with the Kaiser, attempts were made by British intelligence to assassinate V.N. Chatterjee while he was on his way to Geneva to invite Pratap to Berlin. British agents were present in Constantinople, Cairo, and Persia. Their main efforts were directed at intercepting the expedition before it could reach Afghanistan, and thence to exert pressure to ensure that the Emir maintained his neutrality. Under the efforts of Sir Percy Sykes, British intelligence officers in Persia intercepted communications between the expedition and Prince Reuss in Tehran through various means. Among these were letters captured in November 1915 in which von Hentig gave details of the meetings with the Emir, and messages from Walter Röhr outlining the requirements for arms, ammunition, and men. The most dramatic intelligence coup was a message from von Hentig asking for a thousand Turkish troops and the necessity for "internal revulsions" in Afghanistan if need be. This message found its way to Russian intelligence and thence to the Viceroy, who passed on an exaggerated summary, warning the Emir of a possible coup funded by the Germans and a threat to his life.[49] In mid-1916, intelligence officers in Punjab captured letters sent by the Indian provisional government's Ubaidullah Sindhi to Mahmud al-Hasan, which were addressed to the Turkish authority and the Sharif of Mecca. The letters, written in Persian on silk cloth, were sewn into a messenger's clothing when he was betrayed in Punjab. The event was named the Silk Letter Conspiracy.[66] In August 1915, Mahendra Pratap's private secretary, Harish Chandra, had returned to Switzerland after a visit to India, at which time he had carried messages to various Indian princes. He was captured in Europe in October 1915.[67] Chandra divulged details of the Provisional Government of India and of the expedition. He also gave to British intelligence officers letters from Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg and Mahedra Pratap addressed to Indian princes.[62][68][69] Subsequently, Chandra was sent as a double agent to the United States in 1917 to investigate and report on the revolutionary movement in Washington and the finances of the Ghadar Party.[68] Also used as a double agent was a man by the name of Sissodia who claimed to be from a royal family of Rajputana; he attempted to infiltrate the Germans and the Berlin Committee in Zurich.

Diplomatic measures

[edit]The Afghan Emir was warned by New Delhi of the approach of the expedition even while efforts were underway to intercept it in the Persian desert. After it crossed into Afghanistan, the Emir was asked to arrest the members. However, Habibullah humoured the British without obeying the Viceroy's requests. He told the Viceroy that he intended to remain neutral and could not take any actions that were overtly pro-British. Indian intelligence became aware—after the expedition had already been in Kabul for some time—that they carried with them highly inflammatory letters from the Kaiser and the Turkish Sultan. Through British channels, the Russians voiced their concerns about the Emir's tolerance of the German presence and their intrigues with Pro-German Afghan counsellors.

By December 1915, New Delhi felt it necessary to put more pressure on the Afghans. Communications between the British Empire and Kabul had been hitherto through the Viceroy at Delhi. Acutely aware of the pressure on Habibullah from his pro-German relatives and the strong anti-British feeling among the tribes, Viceroy Hardinge suggested that a letter from King George might help Habibullah maintain his neutrality.[70] Accordingly, George V personally sent a handwritten letter on Buckingham Palace stationery to Habibullah, praising the Emir for his steadfast neutrality and promising an increase to his subsidy.[70] The letter, which addressed Habibullah as "Your Majesty", was intended to encourage Habibullah and make him feel an equal partner in the Empire.[54] It had the intended effect: Habibullah sent verbal communication through British agents in Kabul that he could not formally acknowledge the letter because of political pressure, but he nonetheless sent reassurances he would remain neutral.

Following the draft treaty of January 1916, apprehensions grew in Delhi of trouble from tribes in the North-West Frontier Province. That spring, Indian intelligence received rumours of letters from Habibullah to his tribal chiefs exhorting holy jihad. Alarmed, Hardinge called 3,000 tribal chiefs to a grand Jirga in Peshawar, where aerial bombing displays were held; Hardinge demonstrated the Empire's goodwill by increasing British subsidies to the chiefs.[58] These measures helped convince the frontier tribes that Britain's wartime position remained strong and that Indian defences were impregnable.[58][71]

Influence

[edit]On Afghanistan

[edit]The expedition greatly disturbed Russian and British influence in Central and South Asia, raising concerns about the security of their interests in the region. Further, it nearly succeeded in propelling Afghanistan into the war.[57] The offers and liaisons made between the mission and figures in Afghani politics influenced the political and social situation in the country, starting a process of political change.[57]

Historians have pointed out that in its political objectives, the expedition was three years premature.[59] However, it planted the seeds of sovereignty and reform in Afghanistan, and its main themes of encouraging Afghan independence and breaking away from British influence were gaining ground in Afghanistan by 1919. Habibullah's steadfast neutrality alienated a substantial proportion of his family members and council advisors and fed discontent among his subjects. His communication to the Viceroy in early February 1919 demanding complete sovereignty and independence regarding foreign policy was rebuffed. Habibullah was assassinated while on a hunting trip two weeks later.[72] The Afghan crown passed first to Nasrullah Khan before Habibullah's younger son, Amanullah Khan, assumed power. Both had been staunch supporters of the expedition. The immediate effect of this upheaval was the precipitation of the Third Anglo-Afghan War, in which a number of brief skirmishes were followed by the Anglo-Afghan Treaty of 1919, in which Britain finally recognised Afghan independence.[72] Amanullah proclaimed himself king. Germany was among the first countries to recognise the independent Afghan government.

Throughout the next decade, Amanullah Khan instituted a number of social and constitutional reforms which had first been advocated by the Niedermayer-Hentig expedition. The reforms were instituted under a ministerial cabinet. An initial step was made towards female emancipation when women of the royal family removed their veils; educational institutions were opened to women. The education system was reformed with a secular emphasis and with teachers arriving from outside Afghanistan. A German school that opened in Kabul at one point offered the von Hentig Fellowship, devoted to postgraduate study in Germany. Medical services were reformed and a number of hospitals were built. Amanullah Khan also embarked on an industrialisation drive and nation-building projects, which received substantial German collaboration. By 1929, Germans were the largest group of Europeans in Afghanistan. German corporations like Telefunken and Siemens were amongst the most prominent firms involved in Afghanistan, and the German flag carrier Deutsche Luft Hansa became the first European airline to initiate service to Afghanistan.[72]

Soviet Eastern policy

[edit]

As part of their anti-British policies, the Soviet Union planned to foment political upheaval in British India. In 1919, the Soviet government sent a diplomatic mission headed by a Russian orientalist, N.Z. Bravin. Among other works, this expedition established links with the Austrian and German remnants of the Niedermayer-Hentig expedition at Herat and liaised with Indian revolutionaries in Kabul.[73][74] Bravin proposed to Amanullah a military alliance against British India and a military campaign, with Soviet Turkestan bearing the costs.[73] These negotiations failed to reach a concrete conclusion before the Soviet advances were detected by British Indian intelligence.[75]

Other options were explored, including the Kalmyk Project, a Soviet plan to launch a surprise attack on the north-west frontier of India via Tibet and other Himalayan buffer states such as Bhutan, Sikkim, Nepal, Thailand, and Burma through the Buddhist Kalmyk people. The intention was to use these places as a staging ground for revolution in India, as they offered the shortest route to the revolutionary heartland of Bengal.[76] Historians suggest that the plan may have been prompted by Mahendra Pratap's efforts and advice to the Soviet leadership in 1919 when—along with other Indian revolutionaries—he pressed for a joint Soviet-Afghan campaign into India.[77] Under the cover of a scientific expedition to Tibet headed by Indologist Fyodor Shcherbatskoy, the plan was to arm the indigenous people in the North-East Indian region with modern weaponry.[78] The project had the approval of Lenin.[79]

Pratap, obsessed with Tibet, made efforts as early as 1916 to penetrate the kingdom to cultivate anti-British propaganda. He resumed his efforts after his return from Moscow in 1919. Pratap was close to Shcherbatskoy and Sergey Oldenburg. Privy to the People's Commissariat for Foreign Affairs' designs in the region, he intended to participate in the Kalmyk Project to Tibet in the summer of 1919.[77] The planned expedition was ultimately shelved following the Czech uprising on the Trans-Siberian Railway. Pratap set out alone to unsuccessfully pursue his goal.[80]

British India

[edit]The Hindu–German Conspiracy, which had initially led to the conception of the expedition, Pratap's mission in Afghanistan and his overtures to Bolshevik Russia, and the presence of active revolutionary movements in Punjab and Bengal led to the appointment in British India of a sedition committee in 1918, chaired by Sydney Rowlatt, an English judge. In the midst of worsening civil unrest throughout India, it was tasked to evaluate German and Bolshevik links to the Indian militant movement, especially in Punjab and Bengal. On the recommendations of the committee, the Rowlatt Act (1919), an extension of the Defence of India act of 1915, was enforced in India.[81][82][83][84][85]

A number of events that followed the passage of the Rowlatt Act were influenced by the conspiracy. At the time, British Indian Army troops were returning from the battlefields of Europe and Mesopotamia to an economic depression in India.[86][87] The Ghadar Conspiracy of 1915 and the Lahore conspiracy trials were still garnering public attention. News was also beginning to reach India of the Indian Voluntary Corps who, influenced by Ghadarites, fought on behalf of the Turkish Caliphate.[87] Mahendra Pratap was shadowed by British agents—among them Frederick Marshman Bailey—during his journeys to and from Germany and Bolshevik Russia.[88] The Third Anglo-Afghan war began in 1919 in the wake of Amir Habibullah's assassination and institution of Amanullah, in a system blatantly influenced by the Kabul mission. When news of the outbreak of war reached Pratap in Berlin, he returned to Kabul, using air transport provided by Germany.[89]

It was at this time that the pan-Islamic Khilafat Movement began in India. Gandhi, until then relatively unknown on the Indian political scene, began emerging as a mass leader. His call for protests against the Rowlatt Act achieved an unprecedented response of furious unrest and protests. The situation—especially in Punjab—deteriorated rapidly, with disruptions of rail, telegraph, and communication systems. The movement peaked in the first week of April, with some recording that "practically the whole of Lahore was on the streets; the immense crowd that passed through Anarkali was estimated to be around 20,000." In Amritsar, over 5,000 people gathered at Jallianwala Bagh. The situation deteriorated perceptibly over the next few days.[87] The British feared that a more sinister conspiracy for rebellion was brewing under the veneer of peaceful protests.[90] O'Dwyer is said to have believed that these were the early and ill-concealed signs of a coordinated uprising—on the lines of the 1857 revolt—that he expected to take place in May, when British troops would have withdrawn to the hills for the summer. Contrary to being an isolated incident, the Amritsar massacre—as well as responses to other events that preceded and succeeded it—was the result of a concerted plan of response from the Punjab administration to suppress such a conspiracy.[91] James Houssemayne Du Boulay is said to have ascribed a direct relationship between the fear of a Ghadarite uprising in the midst of an increasingly tense situation in Punjab and the British response that ended in the massacre.[92][93]

Epilogue

[edit]After 1919, members of the Provisional Government of India, as well as Indian revolutionaries of the Berlin Committee, sought Lenin's help for the Indian independence movement.[57] Some of these revolutionaries were involved in the early Indian communist movement. With a price on his head, Mahendra Pratap travelled under an Afghan nationality for a number of years before returning to India after 1947. He was subsequently elected to the Indian parliament.[94] Barkatullah and C.R. Pillai returned to Germany after a brief period in Russia. Barkatullah later moved back to the United States, where he died in San Francisco in 1927. Pillai was associated with the League against Imperialism in Germany, where he witnessed the Nazi rise to power. Pillai was killed in 1934. At the invitation of the Soviet leadership, Ubaidullah proceeded to Soviet Russia, where he spent seven months as a guest of the state. During his stay, he studied the ideology of socialism and was impressed by Communist ideals.[95] He left for Turkey, where he initiated the third phase of the Waliullah Movement in 1924. He issued the charter for the independence of India from Istanbul. Ubaidullah travelled through the holy lands of Islam before permission for his return was requested by the Indian National Congress. After he was allowed back in 1936, he undertook considerable work in the interpretation of Islamic teachings. Ubaidullah died on 22 August 1944 at Deen Pur, near Lahore.[96][97]

Both Niedermayer and von Hentig returned to Germany, where they enjoyed celebrated careers.[94] On von Hentig's recommendation, Niedermayer was knighted and bestowed with the Military Order of Max Joseph. He was asked to lead a third expedition to Afghanistan in 1917, but declined. Niedermayer served in the Reichswehr before retiring in 1933 and joining the University of Berlin. He was recalled to active duty during World War II, serving in Ukraine. He was taken prisoner at the end of the war and died in a Soviet prisoner of war camp in 1948. Werner von Hentig was honoured with the House Order of Hohenzollern by the Kaiser himself. He was considered for the Pour le Mérite by the German Foreign Office, but his superior officer, Bothmann-Hollweg, was not eligible to recommend him since the latter did not hold the honour himself. Von Hentig embarked on a diplomatic career, serving as consul general to a number of countries. He influenced the decision to limit the German war effort in the Middle East during World War II.[94] In 1969, von Hentig was invited by Afghan King Mohammed Zahir Shah to be guest of honour at celebrations of the fiftieth anniversary of Afghan independence. Von Hentig later penned (in German) his memoirs of the expedition.[94]

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Hughes 2002, p. 450

- ^ a b c Hughes 2002, p. 452

- ^ a b Hoover 1985, p. 251

- ^ Strachan 2001, p. 798

- ^ Hoover 1985, p. 252

- ^ Brown 1948, p. 300

- ^ Yadav 1992, p. 29

- ^ Hughes 2002, p. 449

- ^ a b c Hughes 2002, p. 451

- ^ a b Hughes 2002, p. 453

- ^ a b Jalal 2007, p. 105

- ^ a b Reetz 2007, p. 142

- ^ Ansari 1986, p. 515

- ^ Qureshi 1999, p. 78

- ^ Qureshi 1999, pp. 77–82

- ^ a b Hopkirk 2001, p. 85

- ^ a b c d e f Hughes 2002, p. 455

- ^ Hopkirk 2001, p. 98

- ^ a b c d Hughes 2002, p. 456

- ^ Popplewell 1995, p. 234

- ^ Hughes 2002, p. 457

- ^ a b c d Hopkirk 2001, p. 99

- ^ Hopkirk 2001, p. 121

- ^ a b Hughes 2002, p. 458

- ^ a b c d e Hughes 2002, p. 459

- ^ a b c d e Hughes 2002, p. 460

- ^ Hughes 2002, p. 461

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hughes 2002, p. 462

- ^ a b c d e f g Hughes 2002, p. 463

- ^ Hopkirk 2001, p. 136

- ^ a b Hopkirk 2001, p. 137

- ^ Hopkirk 2001, p. 138

- ^ Hopkirk 2001, p. 139

- ^ a b c Hopkirk 2001, p. 141

- ^ Hopkirk 2001, p. 142

- ^ a b c Hopkirk 2001, p. 143

- ^ Hopkirk 2001, p. 144

- ^ Hopkirk 2001, p. 125

- ^ a b Hopkirk 2001, p. 150

- ^ Hopkirk 2001, p. 151

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hughes 2002, p. 464

- ^ Hopkirk 2001, p. 154

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hughes 2002, p. 465

- ^ a b c d e Hughes 2002, p. 466

- ^ Hopkirk 2001, p. 160

- ^ a b c Hopkirk 2001, p. 161

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hughes 2002, p. 467

- ^ a b Hopkirk 2001, p. 162

- ^ a b c d e f Hughes 2002, p. 468

- ^ a b c d e Hughes 2002, p. 469

- ^ Hopkirk 2001, p. 165

- ^ a b Sims-Williams 1980, p. 120

- ^ Seidt 2001, p. 1,3

- ^ a b c d e f Hughes 2002, p. 470

- ^ Ansari 1986, p. 516

- ^ a b c d Andreyev 2003, p. 95

- ^ a b c d Hughes 2002, p. 474

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hughes 2002, p. 471

- ^ a b c d e Hughes 2002, p. 472

- ^ a b c Hopkirk 2001, p. 217

- ^ a b c Seidt 2001, p. 4

- ^ a b c Strachan 2001, p. 791

- ^ Hughes 2002, p. 275

- ^ Collett 2006, p. 144

- ^ a b c Collett 2006, p. 145

- ^ Collett 2006, p. 210

- ^ Popplewell 1995, p. 227

- ^ a b Popplewell 1995, p. 230

- ^ McKale 1998, p. 127

- ^ a b Hopkirk 2001, p. 157

- ^ Hopkirk 2001, p. 158

- ^ a b c Hughes 2002, p. 473

- ^ a b Andreyev 2003, p. 83

- ^ Andreyev 2003, p. 86

- ^ Andreyev 2003, p. 87

- ^ Andreyev 2003, p. 88

- ^ a b Andreyev 2003, p. 96

- ^ Andreyev 2003, p. 91

- ^ Andreyev 2003, p. 92

- ^ Andreyev 2003, p. 97

- ^ Lovett 1920, pp. 94, 187–191

- ^ Sarkar & Lovett 1921, p. 137

- ^ Tinker 1968, p. 92

- ^ Popplewell 1995, p. 175

- ^ Fisher & Kumar 1972, p. 129

- ^ Sarkar 1983, pp. 169–172, 176

- ^ a b c Swami 1997

- ^ Bailey & Hopkirk 2002, pp. 224–227

- ^ Bailey & Hopkirk 2002, p. 223

- ^ Collett 2006, p. 222

- ^ Cell 2002, p. 67

- ^ Brown 1973, p. 523

- ^ Tuteja 1997, pp. 26–27

- ^ a b c d Hughes 2002, p. 475

- ^ Schimmel 1980, p. 235

- ^ Jain 1979, p. 198

- ^ Schimmel 1980, p. 236

General and cited references

[edit]- Andreyev, Alexandre (2003), Soviet Russia and Tibet: The Debacle of Secret Diplomacy, 1918–1930s, Boston: Brill, ISBN 90-04-12952-9.

- Ansari, K. H. (1986), "Pan-Islam and the Making of the Early Indian Muslim Socialist", Modern Asian Studies, 20 (3), Cambridge University Press: 509–537, doi:10.1017/S0026749X00007848, S2CID 145177112.

- Bailey, F.M.; Hopkirk, Peter (2002), Mission to Tashkent, Oxford: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280387-5.

- Brown, Emily (May 1973), "Book Reviews; South Asia", Journal of Asian Studies, 32 (3), Pacific Affairs, University of British Columbia: 522–523, ISSN 0030-851X.

- Brown, Giles T. (August 1948), "The Hindu Conspiracy, 1914–1917" (PDF), Pacific Historical Review, 17 (3), University of California Press: 299–310, doi:10.2307/3634258, ISSN 0030-8684, JSTOR 3634258.

- Cell, John W. (2002), Hailey: A Study in British Imperialism, 1872–1969, Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-52117-3.

- Collett, Nigel (2006), The Butcher of Amritsar: General Reginald Dyer, London; New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, ISBN 1-85285-575-4.

- Desai, A.R. (2005), Social Background of Indian Nationalism, Bombay: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 81-7154-667-6.

- Fisher, Margaret W.; Kumar, R. (1972), "Essays on Gandhian Politics. the Rowlatt Satyagraha of 1919 (in Book Reviews)", Pacific Affairs, 45 (1), Pacific Affairs, University of British Columbia: 128–129, doi:10.2307/2755297, ISSN 0030-851X, JSTOR 2755297.

- Hoover, Karl (May 1985), "The Hindu Conspiracy in California, 1913–1918", German Studies Review, 8 (2), German Studies Association: 245–261, doi:10.2307/1428642, ISSN 0149-7952, JSTOR 1428642.

- Hopkirk, Peter (2001), On Secret Service East of Constantinople, Oxford; New York: Oxford Paperbacks, ISBN 0-19-280230-5.

- Hughes, Thomas L. (October 2002), "The German Mission to Afghanistan, 1915–1916", German Studies Review, 25 (3), German Studies Association: 447–476, doi:10.2307/1432596, ISSN 0149-7952, JSTOR 1432596.

- Jalal, Ayesha (2007), "Striking a just balance: Maulana Azad as a theorist of trans-national jihad", Modern Intellectual History, 4 (1), Cambridge University Press: 95–107, doi:10.1017/S1479244306001065, ISSN 1479-2443, S2CID 146697647.

- Jain, Naresh Kumar (1979), Muslims in India: A Biographical Dictionary, New Delhi: Manohar, OCLC 6858745.

- James, Frank (1934), Faraway Campaign, London: Grayson & Grayson, OCLC 565328342.

- Lovett, Sir Verney (1920), A History of the Indian Nationalist Movement, New York: Frederick A. Stokes, ISBN 81-7536-249-9

- McKale, Donald M (1998), War by Revolution: Germany and Great Britain in the Middle East in the Era of World War I, Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, ISBN 0-87338-602-7.

- Popplewell, Richard J. (1995), Intelligence and Imperial Defence: British Intelligence and the Defence of the Indian Empire 1904–1924, Routledge, ISBN 0-7146-4580-X.

- Qureshi, M. Naeem (1999), Pan-Islam in British Indian Politics: A Study of the Khilafat Movement, 1918–1924, Leiden; Boston: Brill, ISBN 90-04-11371-1.

- Reetz, Dietrich (2007), "The Deoband Universe: What Makes a Transcultural and Transnational Educational Movement of Islam?", Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 27 (1), Duke University Press: 139–159, doi:10.1215/1089201x-2006-049, ISSN 1089-201X, S2CID 143345615.

- Sarkar, Benoy Kumar; Lovett, Verney (March 1921), "A History of the Indian Nationalist Movement", Political Science Quarterly, 36 (1), The Academy of Political Science: 136–138, doi:10.2307/2142669, hdl:2027/mdp.39015009367007, ISSN 0032-3195, JSTOR 2142669.

- Sarkar, Sumit (1983), Modern India, 1885–1947, Delhi: Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-90425-1.

- Seidt, Hans-Ulrich (February 2001), "From Palestine to the Caucasus-Oskar Niedermayer and Germany's Middle Eastern Strategy in 1918", German Studies Review, 24 (1), German Studies Association: 1–18, doi:10.2307/1433153, ISSN 0149-7952, JSTOR 1433153.

- Schimmel, Annemarie (1980), Islam in the Indian Subcontinent, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 978-90-04-06117-0.

- Sims-Williams, Ursula (1980), "The Afghan Newspaper Siraj al-Akhbar. Bulletin", British Society for Middle Eastern Studies, 7 (2), London: Taylor & Francis: 118–122, doi:10.1080/13530198008705294, ISSN 0305-6139.

- Strachan, Hew (2001), The First World War. Volume I: To Arms, Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-926191-1.

- Stürmer, Michael (2000), The German Empire, 1870–1918, New York: Random House, ISBN 0-679-64090-8.

- Swami, Praveen (1 November 1997), "Jallianwala Bagh revisited", The Hindu, archived from the original on 28 November 2007, retrieved 10 January 2013.

- Tinker, Hugh (October 1968), "India in the First World War and after", Journal of Contemporary History, 3 (4), Sage Publications: 89–107, doi:10.1177/002200946800300407, ISSN 0022-0094, S2CID 150456443.

- Tuteja, K. L. (1997), "Jallianwala Bagh: A Critical Juncture in the Indian National Movement", Social Scientist, 25 (1/2): 25–61, doi:10.2307/3517759, JSTOR 3517759.

- Uloth, Gerald (1993), Riding to War, Stockbridge, Hants: Monks, ISBN 0-9522900-0-6.

- Yadav, B.D. (1992), M.P.T. Acharya: Reminiscences of an Indian Revolutionary, New Delhi: Anmol, ISBN 81-7041-470-9.